I appreciate that generally, magazines publish lists like this at the end of the old year, not the beginning of the new one. But to tell the truth, I just plumb forgot to do this. And yesterday, when I remembered, I was so excited about sharing my Pop’s interview with you that I couldn’t make myself wait another day.

So, better late than never, here’s the Best of the 2022 Cosmopolitan Globalist.1 I have to say, as I looked through the past year’s worth of articles, I was surprised— and proud. I didn’t realize we’d published so many good articles this year. Future historians, I think, would find the Cosmopolitan Globalist an excellent chronicle of the year 2022. They would understand the causes and the effects of the past year’s world-shattering events, and they would have a good sense of what it felt like to live through them. I was really pleased to see how good CG was this past year, actually. I don’t know why I didn’t realize it. Probably because the moment after I hit “publish” on an article, I begin worrying about the next one—so I never really take the time to look back.

I’ve taken off all the paywalls. If you’re one of those readers who’s been receiving this newsletter since forever but who’s never pulled the trigger on paying for it, now’s your chance to see what you missed. If you like it, for goodness’ sake, don’t wait until 2024 to read this year’s Cosmopolitan Globalist. It’s really worth it to subscribe! I wouldn’t usually say that with so much conviction, but after spending the day looking things over, I feel unusually confident of it. I can sincerely promise you that if you read the Cosmopolitan Globalist this year instead of all that dreck junk-food journalism out there, you will be much better informed at the end of it. (Have you read the Cosmopolitan Globalist FAQ, by the way?)

1. WHAT DOES VLADIMIR PUTIN WANT? The West, argues Nicolas Tenzer, has failed to grasp the deeply ideological nature of contemporary Putinism. But we cannot confront a threat we don’t understand. “Those determined to believe that some form of rationality governs this regime are condemned to understand nothing about it. Likewise, it is a mistake to remain fixed on Putin’s material objectives—territory, military bases in Syria, areas of influence—or to focus on his diatribes against NATO (which Putin knows perfectly well is no threat to any peaceful state). Even weakening Western liberal democracies is not his ultimate objective, per se; it is at most a tactic in an overall strategy. … What Putin wants is likely infinitely more terrifying—and perhaps that is why Western leaders don’t want to see it … ”

2. LES RUSSOPHILES: Why France just can’t quit Russia. How do we explain that of the five top-polling candidates in France’s presidential election, two were on Moscow’s payroll, one promoted the Party Line for free, another attended communist youth camps in the USSR, and the last one was a self-appointed Putin-whisperer? I asked myself why, exactly, the French can’t stop romanticizing Russia. The answer, of course—as always—is history, dear boy, history.

3. WAR 101. So you’ve been issued an AK-47 and conscripted to defend your homeland. Tecumseh Court, a US Marine combat veteran, tells you what to do next. A guide for Ukrainians—and for anyone who wants to understand war from a professional soldier’s perspective. (This was our most-read series of all time, and deservedly so.)

Part I: An introduction to “Warfighting,” the how-to manual for the US Marines, and its practical application in Ukraine.

Part II: Understanding the Main Effort, Intent, and Tactical Leadership.

Part III: Pros talk Logistics.

4. THE NEW CAESARS. A new, illiberal form of governance is spreading mimetically and consolidating itself through the new technologies of the 21st century. Around the world, the New Caesars are emerging from the same larger social, economic, and technological forces. They’re are rapidly learning from each other. In this series, I discuss the political trend that defines our era:

Part I: Introduction

Part II: The demos, the ochlos, and the people’s will

Part III: On the downfall of the Roman Republic

Part IV: Caesar and the Internet: Something new under the sun.

5. TANNENBERG REVISITED. Is despotism the cause of Russia’s military failures? Yes, argues Thomas Gregg, who sees in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine echoes of 1914.

6. NOTES ON PETER ZEIHAN. A reader asked me whether I thought the political forecaster Peter Zeihan was on the right track. I found the question so interesting that I replied at length.

If Peter Zeihan is correct, the death of the Queen marks the end of an era in ways far more significant way than we realize. He argues the world will never again have it as good as it did during Queen Elizabeth’s reign, because globalization is coming to an end. It will never again have it anywhere near as good. Deglobalization means deindustrialization. It means deurbanization, depopulation, and decivilization. The world’s population, he prophesies, will soon shrink as much it did during the Black Death, which swept away 60 percent of Europe’s population …

Part I: Is the old world order about to collapse?

Part II Why Zeihan is gloomy

Part III: On geopolitical forecasting

Part IV: On the origins of the Pax Americana

7. CHINA’S WEB. Slowly but surely, writes Vivek Kelkar, China is leveraging its Belt and Road Initiative to make Beijing the center to a vast new web across Asia, spun out of rail links, oil and gas pipelines, and trade. These infrastructure links could create a massive single market that spans the eastern and western shores of the Caspian Sea, Central Asia, Iran, China, South Asia, and East Africa. This could mean a new global power map.

8. THE SOURCES OF RUSSIAN CONDUCT. Dina Khapaeva offers a compelling account of Russia’s ideology, and because it is compelling, deeply unnerving. She writes about the connection between Putin’s re-Stalinization of Russia and a specific version of Eurasianism, one she terms neo-medievalism. Re-Stalinization, she argues, is a mass movement grounded in the unresolved memory of Soviet atrocities. Eurasianism combines the denial of individuality with the promotion of a new social contract based upon medieval views of society, citizenship, and politics. All of these ideas are profoundly enmeshed. Together, they are an ideology—one that could not be more bleak: “The West doesn’t realize how much danger it’s in.”

9. MAKING SENSE OF THE TIGRAY WAR. Credible research puts the Tigray conflict’s death toll—from violence and famine—at 500,000, a number that eclipses the death toll from the war in Ukraine. If newspaper column inches were assigned in proportion to human suffering, Ethiopia would be all you ever read about. But like most of Africa, the conflict receives little news coverage. Meron Gebreananaye and Saba Mah’derom explain who, where, when, what, why, and how.

10. A SYRIAN’S ADVICE TO UKRAINIANS. Adnan Hadad joined the Syrian revolution because he wanted to live freely in his own country. He’s now an exile in Paris. He understands what Ukrainians are now experiencing—and how much worse it can get—in a way most people can’t. Adnan and I spoke about Syria, Ukraine, Putin, Obama, Biden, red lines, US foreign policy, and how the world decides what it cares about.

Introduction: Why didn’t Syria matter? I reflect on suffering in places that just don’t count.

11. THE ZEITENWENDE. Adam Garfinkle argues that Germany’s emergence as a true global power, with a military to match its economy, will shape the future far more than the fate of Ukraine—or even Russia:

Germany has at last decided that enough by way of sackcloth and ashes is enough. Merkel’s decision was the key. The moral albatross Germans carried before 2015, though lighter as years passed, was unlimited. No mortal can wrap his mind around enormities so vast as those Germany committed between September 1939 and April 1945. A new Germany required a similarly unlimited symbol to break the spell. In one day, Germany froze into psychic amber the memory of trains leaving German soil, packed with the victims of German insanity, en route to labor and death camps to the east. It replaced it with the image of Germans welcoming victims of others’ insanity to refuge in Germany, fromthe east. What’s more, when Angela Merkel said, “We can do this,” she was correct. Syrian refugees have done fairly well after a wobbly start, and they have done well in large part due to German determination to ensure they do well.

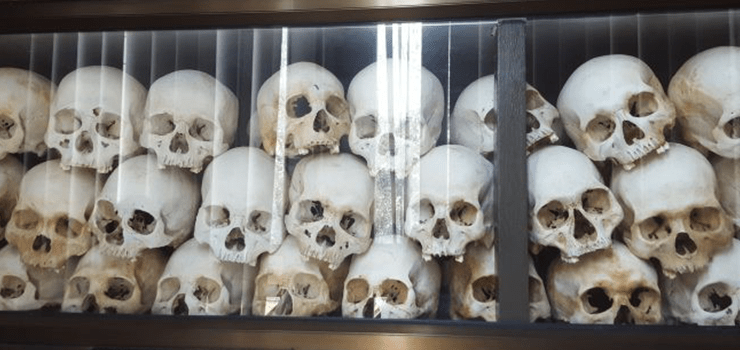

12. THE BEST OF TIMES. My father, David Berlinski, treats Steven Pinker’s claim that violence has been steadily declining for 800 years and indeed that we live in the most peaceful time in history. Of course I’m not impartial, but I think this is an extraordinary essay, one of the best my father has written.

In the face of its crimes, what can one say about the twentieth century beyond what Elias Canetti said: “It is a mark of fundamental human decency to feel ashamed of living in the twentieth century.” What one is not prepared to say, and still less to encounter, largely because it is, at once, absurd and obscene, is the view that the great crimes of the twentieth century were, all things considered, not so bad. This is the view that Pinker defends.

And a bonus …

LUXE, CALME ET VOLUPTÉ. My family and I spend a week in a lush apple orchard at the confluence of the Lot and Garonne rivers:

The rest of my family is out exploring the countryside, looking for the perfect vineyard to find the perfect wine to go with desert. We have become connoisseurs of the local Monbazillac—a wine made only in this region of southwestern France. It’s a cousin of the Sauterne, but it tastes of apricot and honey—it has something to do with the way, in the fall, the morning mists are followed by full sun, or something like that; the explanation made sense when I heard it, but I’ve forgotten the details. I know that if you drink it with a fresh Gariguette strawberry tart, drizzled with caramelized sugar and accompanied by a crispy meringue, whipped cream with vanilla bean, and edible flowers—then follow it with a Partagas Series E no. 2—you will be persuaded that God loves you and wants you to be happy.

Happy New Year, once again! Here’s to 2023, which one in ten of you believe will be the year in which we’re visited by extraterrestrials or find proof of their existence. Should it happen, we will report. And trust me, that will be behind the paywall, so …

You may be wondering why some of the articles are on Substack and others on our website. It’s because formatting and posting the articles on the website proved a major time sinkhole. I just couldn’t keep up with it. It was maintaining the site or writing, and I figured the latter was more important. Also, we don’t know why, but only about half of you ever clicked through to the site, which was demoralizing. We never formally made a decision to let it lapse, but at some point I threw up my hands and said, “Someone else has to do this.” The site isn’t gone, but until we can afford to hire someone to maintain it, it’s on hold.

If enough of you subscribe this year, though, perhaps we’ll try again. I’d like us to have a nice website, and we did invest a lot of time and money in building it. But there’s only one of me, and there’s just a limit to what I can do.