Part I: Introduction

Part II: The Demos, the Ochlos, and the People’s Will

Welcome! I’m afraid we had to put this behind the paywall—as Dr. Johnson reminds us, no man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money.

That said, we’ve taken the paywall off of the introduction to this series on the New Caesarism—the political trend that defines our century. That should give you a good sense of whether you’d find it valuable to subscribe.

If you’re tremendously eager to read it but just can’t afford it right now, there’s good news. One of our generous subscribers has donated two subscriptions for worthy readers. Tell us why you’d like it and one of those subscriptions could be yours:

Countries may be afflicted with Caesarism in different ways and to different degrees. Some countries, such as the UK, have had a flirtation with it, but will probably fight it off. Others, such as the United States, are battling a raging infection—it’s touch and go. As the disease matures, countries develop severe Caesarism, which we see in Turkey and Hungary, for example.

So gravely did we conflate democracy and liberalism, not only in our own minds, but in the minds of most of the world, that we’ve achieved the most bitter of foreign policy victories, a victory we cannot even really describe, because our vocabulary is no longer adequate to describe it.

Then there is the end stage of the disease, represented by Putin’s Russia. The disease may be described, at this point, as outright authoritarianism—although note, it is still inaccurate to describe it as fascism, even if there are important points of commonality between Putin’s Russia and the fascist regimes of the 1930s, particularly in the regime’s use of nationalism and ethnic chauvinism as a unifying myth and justification for imperialism. The differences, however, remain significant. Putin still makes a point of holding elections, which he pretends to believe are important. He derives his legitimacy from winning them, even if the elections are anything but free and fair. Nor does Putin ascribe to fascism’s theoretical apparatus. So Russia’s system of governance is still better described as Caesarian, albeit at an advanced stage.

In using the word “stage,” I mean only to suggest that these regimes exist along a continuum. I don’t mean that they inevitably progress from one stage to the next. History has no teleology. No trajectory is inevitable. It’s fully possible for a country to experiment with Caesarism—for example, by electing a politician whose style and rhetoric conforms to the archetype—then recover by punting him out at the next election. But the further the disease progresses, the less likely this is. Over time, the New Caesars bring every countermanding power center under their control, making it harder and harder to oppose them democratically. So early treatment is essential. By the time the Caesar is proposing constitutional referenda, it’s too late. If he wins, it’s game over.1

In the discussion that follows, I describe politicians, parties, and countries that may be described as Caesarian to various degrees. Some countries are much further along the trajectory than others. But there is a trajectory, which is important. You may not recognize your country in all of these descriptions. Perhaps you’ve noticed one or two symptoms. Perhaps your leader’s personality is somewhat Caesarian, but he hasn’t been particularly effective in arrogating all the power to himself. If you’ve told yourself there’s no cause for concern because things still seem quite normal and your liberal traditions are robust, that is, in my view, a mistake. Most countries, once they put someone like this in power, do follow a fairly predictable path, and you’d be astonished how quickly a liberal culture can disappear.2

You may get lucky. But if you ask me, it’s not worth the risk.

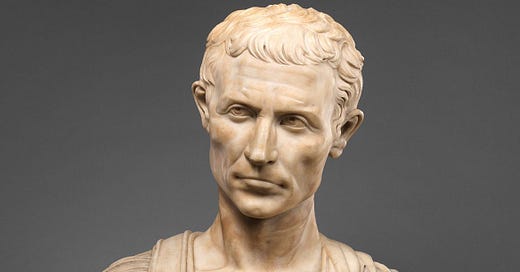

The Old Caesarism

I’ve chosen to call this political phenomenon the New Caesarism because it arises in circumstances reminiscent of those that destroyed the Roman Republic. When Lewis Namier used the term Caesarian democracy, the phrase evoked, as it was meant to do, the demise of the Roman Republic at the close of the First Century B.C. Aspects of Caesarian democracy have since reappeared at regular intervals in Western history; Namier was writing of Napoleon III.

My use of the term is a tribute, too, to Amaury de Riencourt, who in 1958 wrote The Coming Caesars, a remarkable and little-appreciated book. “A few decades from now,” wrote The New York Times when the book was published, “some later historian may dig out this book and proclaim him a prophet.”

Here I am. I proclaim him a prophet. Here is his prophecy. “Our Western world,” he writes, “is threatened with Caesarism on a scale unknown since the dawn of the Roman Empire.”

Caesarism is not a dictatorship, not the result of one man’s overriding ambition, not a brutal seizure of power through revolution. It is not based on a specific doctrine or philosophy. It is essentially pragmatic and untheoretical. It is a slow, often century-old, unconscious development that ends in the voluntary surrender of a free people escaping from freedom to one autocratic master.

De Riencourt makes the case that the evolution of the classical world and our own are parallel and symmetrical. If we superimpose a thousand years of Greek Culture, beginning with Homer, over a thousand years of European culture, beginning in the early Gothic period, “we can roughly estimate our present historical position,” he writes. His book is an effort to do just that, and while at times the analogy is strained—of course it is, history never exactly repeats itself—it works much better than you might at first think.

Not only does the United States have a Roman culture, he avers, but a Roman future. He specifically predicts that Caesarism will emerge in the United States, not Europe—a remarkable prophesy to make in 1958, given the fresh memory of Europe’s experiments with fascism. But he predicts this confidently:

It is in Washington and not in London, Paris, or Berlin that the Caesars of the future will arise. It will not be the result of conspiracy, revolution, or personal ambition. It will be the end result of an instinctive evolution in which we are all taking part like somnambulists.

Why? His argument is complex. It’s hard to summarize neatly without making it sound stupid, which it isn’t. But he draws a distinction between a culture and a civilization, arguing that Greece and Europe represent the former while Rome and America represent the latter. Culture, in his view, creates new values, emphasizing the individual rather than society. Civilization is the expression on a gigantic scale of the preceding culture’s ideas, a mass society that ends inevitably under a Caesarian ruler.

He observes that the American president is already endowed with “powers of truly Caesarian magnitude” that permit him to “make the weight of his incalculable power felt with immediate and crushing speed” anywhere in the world. But “[t]he prime element in this situation is neither political nor strategic,” he writes. “It is essentially psychological.”

It is the growing “father complex” that is increasingly evident in America, the willingness to follow in any emergency, economic or military, the leadership of one man. It is the growing distrust of parliaments, congresses, and all other representative assemblies, the growing impatience of Western public opinion at their irresponsibility, lack of foresight, sluggishness, and indecisiveness. This distrust and impatience is evident in America as in Europe. Further, it is the impulsive emotionalism of American public opinion, which swings wildly from apathetic isolationism to dynamic internationalism, lacks continuity in its global views, stumbles from one emergency into another, and mistakes temporary lulls for the long-expected millennium. Such was Rome’s public opinion in the First Century B.C. Each new crisis calls for a strong man and there are always strong men present who are willing to shoulder responsibilities shirked by timid legislatures.

Again, he wrote this in 1958. You could say this is reassuring. Perhaps we’re perennially destined to fear that America is on the verge of Caesarism, but never to cross the threshold? On the other hand, by the end of the First Century B.C., Rome was no longer a Republic.

I won’t rehearse the whole story of the crisis of the Roman Republic here, interesting as it is. I presume you know it already. But a few words from his conclusion will suggest that he may be on to something with this metaphor:

… The irresponsible agitation of political parties in Rome and the disasters in the Orient finally smashed what was left of Rome’s republican institutions. The decadent Senate was totally unable to cope with the situation and Rome drifted again into a new one-man rule, that of Pompeius. In 67 B.C. the popular Assembly, panic-stricken, transferred the administration of the state from the Senate to Pompeius. The elaborate safeguards of Sulla were swiftly brushed aside. It was then that desperate, high-minded Romans began to see the hated specter of monarchy take shape on the horizon.

Public opinion was by and large still in favor of the old constitution of the republic, but without being willing to make the necessary sacrifices to uphold it. Everywhere, it was a sentimental attachment to constitutional forms rather than to the substance of freedom. All that could now be done was support one strong man against another and, eventually, throw Pompeius against Julius Caesar, who had become the leader of the democratic Populares party, standing on a platform of “people and democratic progress.” The struggle was on between two strong men, not between an unavoidable Caesarism and a doomed republic. The conservative Optimates, who believed that they could control strong men like Pompeius and restore the republican institutions, were only fooling themselves. …

Then follows a description of Caesarism upon which I can’t improve:

With Caesarism … the great struggles between political parties are no longer concerned with principles, programs, and ideologies but with men.3 Marius, Sulla, Cato, Brutus still fought for principles. But now, everything became personalized. Under Augustus, parties still existed, but there were no more Optimates or Populares, no more conservatives nor democrats. Men campaigned for or against Tiberius or Drusus or Caius Caesar. No one believed any more in the efficacy of ideas, political panaceas, doctrines, or systems, just as the Greeks had given up building great philosophic systems generations before. Abstractions, ideas, and philosophies were rejected to the periphery of their lives and of the empire, to the East where Jews, Gnostics, Christians, and Mithraists attempted to conquer the world of souls and minds while the Caesars ruled their material existence.

Caesar, he remarks, did not cease power against the wishes of public opinion. He was called into being by a void begging to be filled:

Long before the advent of Augustus, an insidious belief had taken hold of the Roman world. This was the belief in the “indispensable man,” a feeling that becomes so potent at that stage of history that it finally results in canceling the short tenure of office and tends to prolong supreme power almost indefinitely in the hands of the same man.

It was the failure and irresponsibility of Rome’s decadent elites, by his lights, that persuaded the middle class Caesarism would be preferable to chaos under their incompetent stewardship. He makes a point worth considering here: “It was not the republican institutions as such but a high-minded ruling class that had raised Rome above all other nations,” he writes. But Rome had destroyed its ruling class. How so? Through democracy.

It’s not entirely surprising that Reincourt traces the downfall of the Roman republic to the destruction of its aristocratic class. Reincourt, a descendant of one of the oldest families in France, had a soft spot for aristocrats. His argument probably won’t go down well with Americans. But that, he argues, is precisely the problem. I’ll give him this: When you watch the video of JFK during the Cuban missile crisis and compare it to a video of any of our recent presidents struggling to choke out a single coherent thought, you can’t help but suspect we’ve taken this “democracy” business too far.

By this I don’t mean we’ve taken free and fair elections too far. I mean—as Reincourt did—that we’ve taken the egalitarian principle that underpins democracy too far. We no longer demand that the president be an exceptionally gifted man. We demand he be as mediocre as the rest of us. I first noticed this when Sarah Palin rose to prominence, as I wrote at the time:

The collective American desire for an “authentic” president, as opposed to a presidential president, is more than passing strange, seemingly the expression in psychic terms of a primitive but very powerful form of radical egalitarianism—a kind of communism of the soul. What is primitive communism, after all, whether in the Gospels or the Soviet Union, but a commitment to the thesis that no one is any better than anyone else, and no one should aspire to be? Yet it is self-evidently true that anyone who would be good at being the president of the United States would be vastly more impressive than an average person. The healthy desire for one’s leaders to empathize with ordinary people has been conflated with the desire for a leader who is an ordinary person. No sensible patient would choose his cardiovascular surgeon on the grounds that the man seemed like an average, forgetful klutz. When it comes to certain jobs, most would acknowledge they are best done by those on the very far side of the Bell Curve.

The same impulse is at work in proposals to abandon rigorous academic standards on the grounds that so long as they endure, some people won’t succeed. It is a matter of taking the democratic principle—all men are equal—much further than it can be usefully applied. This tendency, Reincourt argues, destroyed the Roman elite, and would destroy the American elite, too:

Under present conditions, democratic equality ends inevitably in Caesarism. No system of checks and balances can hold out against this profound evolution, a psychological alteration that bypasses specific institutions. The thirst for equality and distrust of any form of hierarchy has even weakened Congress itself through its seniority rule. Dislike for aristocratic distinctions eventually ends by eliminating that most indispensable of all elites—the aristocracy of talent.

He was writing in the future tense. But we can safely say that by now, our high-minded ruling class no longer exists. It has gone the way of Rome’s. That Herschel Walker and J.D. Vance are poised to join our elite surely signifies the public’s belief that this elite should be composed of men whom you might find sitting next to you, inebriated, on a Greyhound bus. It’s a spectacularly egalitarian sentiment—admirable, in that sense—but it’s insane.4

In any event, once that aristocracy is gone, it’s gone:

Augustus was wise enough to know that it was the decadence of the ruling class and the trend toward democratic equality that had led directly to Caesarism. He knew that liberty thrives only on a certain amount of inequality and nonconformity. But there was no more ruling class, only an owning class of new rich, the spineless novi homines who could substitute socially, but never politically, for the fallen aristocracy. Augustus could not stem the tide of history, although he was not the last one to try. Austere, stern, and unbending, Tiberius tried to instill self-reliance into the Senate, refused to allow it to take an oath to support all his decisions and, in exasperation at the contemptible fawning of which he was the object, exclaimed in despair: “O men, ready for slavery!”

The American founders consciously imitated Rome. It should not then surprise us that we have Roman problems. Avid students of classical history, they knew intimately the story of Rome’s downfall. They understood that democracy and liberty were not identical and indeed in tension, and they grasped the implications of this. “Of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics,” Alexander Hamilton warned, “the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.”

What Hamilton feared is precisely what is now happening to established constitutional orders the world around—and certainly not just ours, contra Reincourt. We’ve been slow to recognize the threat it poses because—again, contra Reincourt—in some respects it’s unlike anything humanity has seen before, exploiting as it does technologies of which we have no experience.

But we’ve also been confused because we’ve assigned too much significance to the fact of democracy. These regimes are, at least at first, genuine democracies, where rulers enjoy real popularity. If you’ve conflated democracy with liberalism, you won’t grasp that a democratically-elected government can indeed be one to worry about.5

That said, we really should understand this better by now. In 1997, Fareed Zakaria wrote an essay discussing this regime type in Foreign Affairs. This was, as far as I can tell, the first widely-published description of this phenomenon:

The American diplomat Richard Holbrooke pondered a problem on the eve of the September 1996 elections in Bosnia, which were meant to restore civic life to that ravaged country. “Suppose the election was declared free and fair,” he said, and those elected are “racists, fascists, separatists, who are publicly opposed to [peace and reintegration]. That is the dilemma.” Indeed it is, not just in the former Yugoslavia, but increasingly around the world. Democratically elected regimes, often ones that have been re-elected or reaffirmed through referenda, are routinely ignoring constitutional limits on their power and depriving their citizens of basic rights and freedoms. From Peru to the Palestinian Authority, from Sierra Leone to Slovakia, from Pakistan to the Philippines, we see the rise of a disturbing phenomenon in international life—illiberal democracy.

It has been difficult to recognize this problem because for almost a century in the West, democracy has meant liberal democracy—a political system marked not only by free and fair elections, but also by the rule of law, a separation of powers, and the protection of basic liberties of speech, assembly, religion, and property. In fact, this latter bundle of freedoms—what might be termed constitutional liberalism—is theoretically different and historically distinct from democracy.

As the political scientist Philippe Schmitter has pointed out, “Liberalism, either as a conception of political liberty, or as a doctrine about economic policy, may have coincided with the rise of democracy. But it has never been immutably or unambiguously linked to its practice.” Today the two strands of liberal democracy, interwoven in the Western political fabric, are coming apart in the rest of the world. Democracy is flourishing; constitutional liberalism is not.

This was 1997, and since then, the phenomenon has accelerated. The past decade has seen a global authoritarian revolution. Many of the Caesars now stalking the world stage came to power via elections. So it shouldn’t be quite so hard to accept, in 2022, that democracy is not inherently liberal.

Illiberal democracies

Because winning elections is the key to their legitimacy, the New Caesars are exceptionally skilled at doing so. Their professional political operatives—in Russia, they’re called “political technologists”—are as sophisticated and industrious as their counterparts in the United States, and no wonder, since they’re often the same people. These regimes tend to hire the best in the West and learn from them. In particular, they hire high-powered Western election consultants, PR firms, and advertising agencies. (Of course they hired Paul Manafort. He comes with is a double benefit. He’s good at getting kleptocrats elected and he’s a walking tutorial in state-of-the-art American techniques in election manipulation. That kind of knowledge is invaluable when you’re ready to graduate from manipulating Ukraine’s elections to manipulating American ones. To call such regimes undemocratic is absurd: They are completely committed to holding elections and doing whatever it takes to win both theirs and ours.)

But the goal is not to win an election as we would generally understand it—that is, one in which the outcome is uncertain until election day. It’s to organize a system that appears to be genuinely competitive while ensuring that it’s no such thing. When members of the Russian opposition obtained video evidence of ballot stuffing by Putin’s United Russia party, for example, Putin was outraged, although not for the reasons we might expect. He was livid because it signified the party’s complacency and laziness: If you have to resort to ballot stuffing, you’ve allowed things to get entirely out of hand. The outcome of the election should have been fixed well before election day, and it should have been done elegantly, not crudely—through laws and policies that guaranteed the opposition stood no chance.

Speaking of elegance, unlike their forebears, who proudly displayed the state’s capacity for violence pour encourager les autres, the New Caesars tend to hide their hand in political murders, which become “unsolved mysteries.” Murder is the seasoning, not the meat; it is reserved, in the main, for dissidents, and journalists. (The New Caesars cultivate a special loathing of journalists, who are perennially accused of bias, treason, or lack of patriotism. They repeat these accusations to the point that their followers are rarely overly exercised when journalists meet with misfortune.) The public, generally, understands that the people who get whacked are not really people like them, and thus that they have no special reason to fear. If you don’t mess with Caesar, he won’t mess with you.

Besides, the violence—at least at first—is rare. They have a much subtler touch. If twentieth century dictators demonstratively threw their enemies from helicopters into shark-infested waters, the New Caesars just hack their rivals’ iPhones, commandeer the camera, and leak the inevitable sex tape to their cronies in the media. Little real violence is needed, because the New Caesars are genuinely popular. Voters believe they’re doing a good job, particularly compared to the leaders of other countries, whom they believe to be making of things an anarchic mess.

But why are they so popular? Why do the people believe other leaders are making of things an anarchic mess? If the New Caesars don’t rely on violent repression, how do they stay in control?

By reengineering the electorate. Consider Bertolt Brecht’s response to the East Berlin rising in 1953:

The Secretary of the Authors’ Union Had leaflets distributed in the Stalinallee Which said that the people Had forfeited the government’s confidence And could only win it back By redoubled labor. Wouldn’t it Be simpler in that case if the government Dissolved the people and Elected another?

In effect, the New Caesars dissolve the people and elect another. More precisely, they systematically re-engineer the public’s beliefs about reality. This sophisticated ability to control what the public knows is the essence of New Caesarism.

They don’t rely upon the traditional clumsy tools of censorship to achieve this—or at least, they do not rely primarily on those tools. Instead, they shape the information environment by exploiting the effect that the 21st century’s communication technologies have on our attention.

Precisely because their legitimacy rests upon democracy, the New Caesars are keen to cultivate the illusion of pluralism. Opposition parties are allowed to participate in regular elections. Often they campaign noisily and vigorously. It would not be obvious to a casual visitor that the opposition has been co-opted or defanged. But it has been.

How so? First, through the state’s manipulation of the media and the public’s attention—and thus its sense of reality. But next, and just as important, through the state’s control of the economy. What’s confusing here is that the economy, on superficial inspection, looks free enough, or at least bon pour l’orient, as French colonialists would have had it. The New Caesars have no interest in command economies or autarky; to the contrary, they cultivate extensive economic connections with the rest of the world. (The promises to end globalization disappear after election day. They either know damned well to begin with or realize quickly that fulfilling those promises would swiftly bring the economy to its knees.) They welcome foreign investment.

Because they’re open to the global economy, these regimes are not only more prosperous than their miserable communist forebears, but less apt to invite foreign criticism and pressure to reform. Welcoming foreign investment bolsters the regime’s claim to legitimacy, domestically and abroad. “Don’t be silly, of course we’re free,” it proclaims; “Don’t you see we have a free market?” A corrupt one, to be sure, but free enough to persuade global capital that the country is “on the right path,” or “a promising emerging investment opportunity.” Western investors can make money in these countries. Shrewd ones can make a lot—and that kind of money translates into lobbying power in the US Congress and perennial optimism there about Russia’s (or Turkey’s, or Hungary’s) nascent democracy.

Behind this illusion, however, state enterprises and crony tycoons dominate the economy. With the assistance of a compliant judiciary, the New Caesars and their corrupt entourage set the price of participation, and the price is loyalty to the regime. Punishment for dissent is subtler than it used to be—there’s less of the business with the helicopters and the sharks—but the tax authorities scrutinize your accounts with unusual zeal. Your firm never wins government contracts. Letters of the zoning laws that don’t apply to loyalists apply to you.

The rewards for cooperation aren’t subtle at all, however. If you’re an important player and you support the government, you will have a an oil pipeline, a timber forest, a platinum mine, a football club, a real-estate company incorporated in Cyprus, a home in an upscale neighborhood in London with Carrara marble countertops, a terrific mistress or three—underage gymnasts, perhaps?—whatever you need. And precisely because the economy is open to global investment, there’s always enough cash on hand to buy off or corrupt a challenger who might actually be on the verge of becoming genuinely popular.

What about civil society? As with the opposition parties or the media, a superficial inspection might persuade you that it’s doing well enough. Most NGOs are welcome to set up shop—they’re proof of the country’s “vibrant civil society.” And true enough, civil society organizations that specialize in health issues, say, or education, are warmly received. But life is a bit more challenging for the ones that focus on human rights or political reform. Vaguely worded laws, shepherded through rubber-stamp parliament and enforced by a pliant judiciary, allow these regimes to maintain the twin fiction of rule of law and vibrant civil society and to harass any serious challengers to the point they go broke and give up.

So yes, at least at first, they tend to win elections. But when a politician like this wins an election, the victory is not understood as it would be in a liberal democracy. It’s understood as a comprehensive mandate for any and all of the New Caesar’s policies, without limits. Those who challenge their policies are not viewed, as they would be in a liberal democracy, as the loyal opposition; nor is a robust opposition viewed as an integral, necessary aspect of a healthy democracy. Opponents are viewed as enemies of the will of the people—that is to say, one step short of outright traitors. On this basis, all of this is justified so long as it keeps the disloyal opposition out of power. How many election cycles does it take to complete the process? Two or three is a good start. It doesn’t happen overnight. But it happens faster than you realize. And then there’s no getting rid of them.

This formula is as effective as it is for reasons that are profoundly ironic. A century of American efforts to promote democracy—through example, persuasion, propaganda, rifles, and bombs—was phenomenally successful. We won. The United States persuaded the better part of the world that democracy and only democracy—the holding of regular elections—confers legitimacy upon a regime.

What we failed to realize, however, how easily democracy could be divorced from the liberal consensus that had for generations underpinned the American experiment. For no good reason at all—and certainly contrary to everything the founders of the United States knew and believed—we convinced ourselves that “democracy” entailed these values.

So gravely did we conflate democracy and liberalism, not only in our own minds, but in the minds of most of the world, that we’ve achieved the most bitter of foreign policy victories, a victory we cannot even really describe, because our vocabulary is no longer adequate to describe it.

Somehow, we’ve succeeded in making the world safe for democracy and lethal to freedom.

Next: Why this regime type is genuinely new.

Just ask my grandparents, who came of age in Weimar Germany. This is the extreme example, of course, but liberal traditions can disappear almost overnight. The United States is a good example. Four years of Donald Trump’s presidency eroded American liberalism to a degree I once thought unimaginable. For example, I haven’t seen recent polling numbers, but I’d be surprised if more than 20 percent of the American public agrees with the statement, “I respect the political opposition.”

“But the Democrats are mediocre too!” Yes, they are. Ça va sans dire.

This confusion recently occasioned some of the dumbest comments I’ve seen in the American press, and this is a highly contested category. After the victory of Georgia Meloni’s coalition in Italy’s recent general election, the left insistently described Meloni as a fascist—and the right countered that she couldn’t be a fascist, because a majority of the Italian people had voted for her. (Just for the record, the latter claim isn’t true: Her party took 26 percent of the vote; her coalition, 44 percent.) Talking heads on Fox denounced objections to Meloni as woke histrionics and declared her a conservative after the fashion of Margaret Thatcher. Their knowledge of Meloni was very obviously the product of a single carefully chosen video spoon-fed to them by her PR team. None of them believed that knowing nothing about Italy, and visibly so—or Margaret Thatcher—should be an obstacle to shooting their mouths off. Their opposite numbers on the left, who were equally poorly informed, promptly went into woke histrionics and described Meloni as the new Mussolini, except for good old Hilary Clinton, who apparently wasn’t briefed and declared that it was refreshing to see a woman breaking glass ceilings. All of these views are preposterous, in equal measure, and those offering them should be deeply embarrassed. I did learn something, though: First, Democrats don’t know what “fascist” means; second, Republicans don’t know either, because they seem to think fascists aren’t popular and can’t come to power via elections. (Mussolini did.)

We need to do a better job of teaching history.

The satisfaction I reap seeing my opinions (about democracy v liberalism and about the eerie parallels with ancient Rome) articulated brilliantly by you is over-balanced by sense of impending doom. Above and beyond the sadness of losing our freedom for future generations, especially in America, twenty-first century Earth is not a safe place for a bunch of Caesars to run around in. I'm not clinically depressed, but I think I should be.

Claire, a minor editorial note:

Caesar, he remarks, did not cease (should be SEIZE) power against the wishes of public opinion. He was called into being by a void begging to be filled: