Tactical nukes and Armageddon

Instead of emulating Kennedy's example, we have opted for something untried and uncertain.

By Joshua Treviño

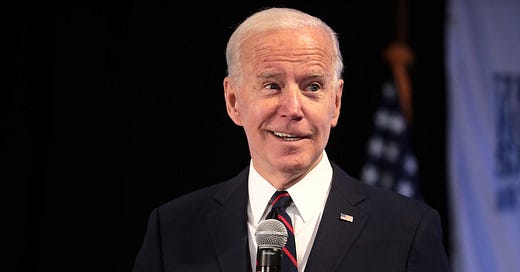

The President of the United States, according to multiple outlets, told a Democratic fundraising event in New York last night that we are in a moment comparable to the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. I’ll let big media deliver the direct quote:

The President’s grasp of history is poor: there have been several close-run nuclear incidents of varying severity since 1962, including the US-Soviet confrontation during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the 1983 Able Archer/Operation RYaN incident, and the 1995 Black Brant episode.1 The President was a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee for most of these, and in the Senate for all of them, so there is no particular reason he would not know.2 The point in this is not to nitpick, but to illuminate. Having been here several times before, and successfully navigated the straits, what lessons can policymakers and leadership draw?

There is no reason to believe the traditional mechanism of deterrence does not work. There is reason to believe we have abandoned the traditional mechanism of deterrence—and moreover that we have told the Russians so.

The relevant lessons are not necessarily obvious or applicable. Taken in aggregate (including a discrete episode within the Cuban Missile Crisis itself), the major historical mechanism saving the world from nuclear conflagration has been Russian officers and leadership, at a variety of levels, who refuse to set in motion a nuclear-weapons attack at the moment of decision. This speaks well of them but it is no basis for policy. (Future historians will have to unfold the paradox of an army that cuts throats with such abandon, and also possesses men of sacrificial restraint who happen to be present when needed by the world.) American policymaking requires something else.

The template for successful navigation of nuclear crises, beyond providential men, is of course rooted in traditional deterrence. Drawing upon the Cuban Missile Crisis, we can note that the then-President doubled down on it, and actually broadened the American nuclear umbrella well beyond what treaty demanded. If you’ve never watched President Kennedy’s full speech to the nation on 22 October 1962—interestingly enough, exactly sixty years ago in just two weeks—it’s worth your time.

Here’s the key passage, coming at the eleventh of the speech’s eighteen minutes:

“It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.”

It’s quite a statement. Although Kennedy explicitly invoked the 1947 Rio Pact in his remarks, that multilateral structure never covered the entire hemisphere. The other hemispheric organization invoked, the Organization of American States, is not a defense pact. The American-governmental response to Soviet nuclear arms in Cuba, then, deliberately foreclosed the option of a Soviet “demonstration” or third-party attack, in declaring an automatic escalation to full strategic-nuclear exchange even if the nation attacked was not an ally of the United States. It was not the only reason the crisis ended peacefully—nothing in history has a singular cause, and trust none who say otherwise—but it was a significant reason. Depriving the Soviets of escalatory options, which is to say communicating American escalation dominance, had the effect of opening them to the eventual compromise that terminated the confrontation.

A parallel in this moment, with the present-day Russian dictator plausibly contemplating nuclear-weapons use against Ukraine, would be for the United States to extend the same nuclear guarantee to Ukraine in 2022 that it extended to even the most picayune Caribbean island and Latin American republic in 1962.

“It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Russia against any nation in Europe as an attack on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Russian Federation.”

It would be reasonably consistent with American strategic policy, as we are a de facto party to the Russia-Ukraine war in any case, and as we have publicly identified the need to curb and diminish Russian war-making as a top-level American interest. Most important, of course, is our compelling interest in avoiding nuclear war and its consequences. (The President, as we shall see below, has views on what those consequences are.) Looking back to the lessons of late 2021 and early 2022, it also has the virtue of having had the contrary case already demonstrated: America’s public refusal to abide by its own guarantees extended to Ukraine had the direct effect of validating the Russian decision to invade. We know they are keenly attuned to our signals in this respect. There is no reason to believe the traditional mechanism of deterrence does not work.

There is reason to believe we have abandoned the traditional mechanism of deterrence—and moreover that we have told the Russians so. (Armas has covered this extensively in the past week: see here, here, here, and here.)3 Instead of emulating the Kennedy example, we have opted for something untried and uncertain in promising a non-nuclear response to nuclear use.

This being the case, the President’s public statements take on a bizarre quality. “I don’t think there’s any such thing as the ability to easily use a tactical nuclear weapon and not end up with Armageddon,” he says, and he may well be right about it. But if this is the case, and the President believes it, then does it not follow that maximum deterrence should be brought to bear against that use? In other words, does not the premise demand the exact opposite of the communicated American policy now? Vladimir Putin is “not joking when he talks about potential use of tactical nuclear weapons,” says the President of the United States, and yet we have eschewed escalation dominance against the prospect.

“We are trying to figure out, what is Putin’s off ramp?” says the President, “Where does he find a way out?” Startlingly, no one seems to have persuaded the President—if they have even mentioned it to him—that the Russian autocrat finds his “way out” in nuclear escalation, fueled and facilitated by the knowledge of an American determination (and in fairness, also a European determination) to exercise restraint when he does it. The parallels with the beginning of this war grow, and they are disquieting in their strength. Something wicked comes, and we dread it, but we promise not to meet it force on force, and—therefore it comes nonetheless.

This too comes nonetheless.

One final note. If the President genuinely believes everything he has said this past evening—a Cuban Missile-Crisis level of danger, a Russian dictator determined to use nuclear arms, escalation to “Armageddon”—then it is by its nature a matter for a President to discuss with the whole nation. There is something unhappy and petty in airing it at a partisan fundraiser, with only pool reports to communicate to the whole citizenry. It speaks directly to the fatal disconnect between ruler and ruled—in the most basic questions of war and peace.4

Joshua Treviño is the Chief of Intelligence and Research at the Texas Public Policy Foundation. He writes at Armas, where this essay was first published, about culture, events, and strategy, with a particular focus on Texas, Mexico, and China.

Postscript from Claire. You may have missed this item in all the excitement: Last Tuesday, at 7:30 a.m., sirens and cellphone alarms began blaring and ringing throughout northern Japan. Why? Because without warning, North Korea shot an intermediate-range ballistic missile over Japanese territory. An unannounced launch endangers aircraft and ships, obviously—would you like to be in a commercial aircraft while that thing’s sailing through the air?—and had it fallen short of its target, it would have landed on a heavily populated part of Japan.

It was the first time in five years they’ve launched a missile over Japan and their twenty-third missile launch this year. It was also their longest flight so far: It travelled 4,600 kilometers before plowing into the Pacific. Guam is only 3,380 kilometers away from North Korea. So North Korea now has the ability to hit US territory.5

Satellite imagery shows activity around North Korea’s underground test site indicating that they’re rebuilding its tunnels. American and South Korean officials think North Korea is preparing for a seventh nuclear test. It would be the first test in five years. It will probably happen after China’s Communist Party Congress in mid-October.

Benjamin R. Young, writing for Nikkei Asia, predicts that North Korea will, in the near future, “use nuclear blackmail to seek a favorable position vis-a-vis the South.” Kim is encouraged, he suspects, but South Korea’s rapidly declining birthrate.

Putin’s nuclear threats aimed at keeping NATO forces out of the Ukraine conflict could embolden Kim to follow suit. Pyongyang may believe that the credible threat of a nuclear attack against US territory could drive Washington to pull its troops out of South Korea and ensnare Seoul into an economic relationship that strongly benefits the Kim family regime.

The way we respond to the crisis in Ukraine will shape Kim’s views about the wisdom of this strategy. Timothy Snyder recently explained why we can’t just instruct Ukraine to surrender and save our skins—a shockingly common suggestion on social media, most recently expressed by a shockingly poorly informed Elon Musk. As Snyder writes:

[G]iving in to nuclear blackmail won’t end the conventional war in Ukraine. It would, however, make future nuclear war much more likely. Making concessions to a nuclear blackmailer teachers him that this sort of threat will get him what he wants, which guarantees further crisis scenarios down the line. It teaches other dictators, future potential blackmailers, that all they need is a nuclear weapon and some bluster to get what they want, which means more nuclear confrontations. It tends to convince everyone that the only way to defend themselves is to build nuclear weapons, which means global nuclear proliferation.

There is only one option: deterrence.

Thomas Gregg recently made the same case. “Let the despot be told in stark, unmistakable terms that the use of nuclear weapons, even on a small scale, would spell the end for him and his regime. It’s just that simple.”

And more. See: False alarms.—Claire.

Let’s not forget the 2017–2018 North Korea crisis, which was extremely grave, and sufficiently recent that I can’t imagine why anyone would have trouble remembering it.—Claire.

He is referring to this and to other clearly authorized leaks:

[W]estern officials said that a nuclear strike against Ukraine would be unlikely to spark a retaliation in kind but would instead trigger conventional military responses from western states to punish Russia.

I agree strongly—in principle. But in the essay to which I linked in the first footnote, False Alarms, I argued (and still believe) that it’s an accident about which we should be most worried: a minor misfire or miscommunication with catastrophic consequences. Biden is incapable of speaking clearly and precisely, which is a liability in a president under the best of circumstances, but truly a dangerous one at a time like this. His comment that we haven’t faced the prospect of Armageddon since Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis is a case in point. He’s left us to wonder whether he was just speaking sloppily or if he really doesn’t know the relevant history. He needs to know that history, because he needs fully to grasp that the biggest risk we face right now is, precisely, an accident. He was probably just speaking sloppily, as usually he does—being his typical inarticulate self. But I have zero confidence he could make it through a speech to the nation without tripping over his own tongue and, at best, suggesting dementia when really that’s not the best look for us right now, and at worst being the source of a miscommunication with catastrophic consequences. Under these circumstances, perhaps it’s best he says nothing, particularly given this portrait of Putin’s state of mind.

By the by, I’ve had it with presidents who can’t speak clearly or appropriately about matters of grave significance. What do you say, my fellow Americans: If we survive this, shall we not elect any more of them? We really need to think more carefully about who we give the power to launch on command. The contrast between JFK and our recent presidents does not reflect well on us as an electorate.—Claire.

In response, South Korea tried and failed to launch a missile, which crashed, terrifying residents of Gangneung, who heard the explosion, saw flames leaping from the nearby military base, and thought the war had begun. The whole world is on a hair trigger. This is why I worry about accidents.

I was sitting in the early morning at the Molokai airport in January 2018. Then came over my phone, and the phones of others, an alert was broadcast warning of inbound ballistic missile. It noted that this was not a drill. For several minutes the sinking feeling of doomsday hopelessness and inevitability sunk in. Shock, anger, rationalization, and then acceptance all in a minute or two.

It really happened, and then it didn’t. An error occurred, a technician at a computer choosing the wrong option on a menu. I wondered what if we had retaliated before discovering the truth.

Bullies must be meant with strength, straight up and face to face. There is no alternative. I fear a weak, equivocating president at this moment and it does not bode well for the world.

I’ve thought of this quote for a long time. I don’t know who first said it but it’s one I think we all should ruminate on. “Little by little the face the nation changes, by the men we choose to admire”.

To some extent at least, deterrence is a built-in feature of nuclear weapons. Even if there are no specific statements on the record, the side contemplating their use cannot be sure that a response in kind would not follow. It may even be that such uncertainty is preferable to specific statements of policy, which may be thought to lack credibility.

That’s why my suggested warning to V. Putin is not specific: Let him wonder about the details. For after all, there exist today some pretty destructive non-nuclear military options not previously available. Great pain could be inflicted on Russia without resorting to the Bomb.

One other point. I have a sense that if Putin did order a nuclear strike or demonstration, that could precipitate him and his regime into a terminal crisis. And he itself may fear this. However that may be, I think we can safely assume that his decision to make war on Ukraine and its disastrous results have weakened his position. It may seem paradoxical, but his resort to nuclear threats signifies that weakness.