China's web

With massive infrastructure investments across Central Asia and Iran, China is trying to build a vast trade net across Asia.

Vivek Y. Kelkar, Mumbai

Just two days before the September 15 meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization in Samarkand, the Chinese government’s mouthpiece, Global Times, announced that Xi Jinping’s presence at the meeting—his first foreign trip since the pandemic began—would “inject more Chinese wisdom” into the SCO, which remained “cohesive and attractive to potential new members.”

Until last week, the SCO was an eight-member group comprising China, India, Russia, Pakistan, and the Central Asian republics of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Kazakhstan. When the meeting concluded, Chinese “wisdom” and the attractiveness of the region were apparent: Iran signed on as a full member. Turkey, hitherto a special invitee, formally expressed an interest in full membership.

China’s promise of money, know-how, and investment in infrastructure and trade across the region seems momentous. Slowly but surely, China is leveraging its Belt and Road Initiative to make Beijing central to a vast new web across Asia, spun out of rail links, oil and gas pipelines, and trade. These infrastructure links could create a massive single market that spans the eastern and western shores of the Caspian Sea, Central Asia, Iran, China, South Asia, and East Africa.

This could mean a new global power map. Iran’s Foreign Minister Hossein Amir Abdollahian hinted as much when several days ago he announced on Instagram: “By signing the document for full membership of the SCO, now Iran has entered a new stage of various economic, commercial, transit and energy cooperation.” Iran now has options beyond the West, and especially beyond the United States, for trade and investment. Gradually, Central Asia is becoming pivotal to Asian geopolitics.

But there’s a flaw in China’s strategy. Africa has proven that China’s investments in infrastructure, though vast, create massive debt problems for the recipients. So Xi’s wisdom may in reality be folly: The Beijing gambit may not work quite the way Xi and his cronies envisage.

Money for Central Asia

Just before the SCO met, there was another portentous announcement—China would finance and build a new 523-kilometer-long China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway line. The deal was formally ratified in Samarkand. Work is expected to start in spring 2023.

The line will connect China, via Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan, to the city of Turkmenbashi on the Caspian, Azerbaijan, and Turkey. Then it would go to Bulgaria and Romania. This cuts 900 kilometers off the existing East-West China-Europe freight railway line, which goes through Russia—and which the new route would allow China completely to bypass.

The railway would also link China to the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz via the International North-South Corridor to Bandar Abbas and the Turkmenistan-Iran link to the Chahbahar port. It will be the shortest route for freight between Europe, China, the Middle East, East Africa, and India. For China, this would be an alternative to the beleaguered China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, which is behind schedule thanks to the Balochistan insurgency.

The countries of Central Asia will be better connected to each other. The old rail links led to Russia, thanks to the legacy of the Soviet Union. But in recent years, Uzbekistan has built railway lines to Turkmenistan so better to gain access to the Caspian and to the Azerbaijani port of Baku, which connects it to Europe. These new rail connections will allow Iran and Central Asia to export fossil fuels and minerals, such as uranium, to some of the world’s fastest-growing economies—all in Asia.

China is also financing and building a cross-border trade and logistics center in Kyrgyzstan’s Kyzyl-Kiya, which will make cross-border freight more efficient, as well as a textile cluster and a machine-tractor park in the Jalal-Abad region of Kyrgyzstan.

Throughout the region, supply chains for cement, coal, quartz, sand, and even potatoes are being built. These can be extended to China and the rest of Asia, and even to Africa, via two land routes—one through Iran to India and East Africa, and the other through Iran or China to Southeast Asia.

These new trade routes have enhanced the confidence of the Central Asian nations. They’re keen to secure trade deals not just with China but Europe, too, reducing their dependence on Russia. Uzbekistan, for instance, recently signed free trade agreements with Britain and the European Union. Tashkent issued its first Eurobond in 2020, followed by a Sovereign Sustainable Development Goals bond in 2021.

Uzbekistan will privatize fifteen major state-owned enterprises in the coming two years. Europe and China can be expected to participate in the process, and global finance could buy some of the equity. India, too, wants to invest in Central Asian companies.

China has invested heavily in oil and gas across the region. In Kazakhstan alone, it’s put nearly US$1.5 billion into natural gas infrastructure. The Kazakh-China cross-border pipeline, which traverses parts of Russia, and the Turkmenistan-Xinjiang gas pipeline make Beijing the key economic player in the region.

The Iran Game

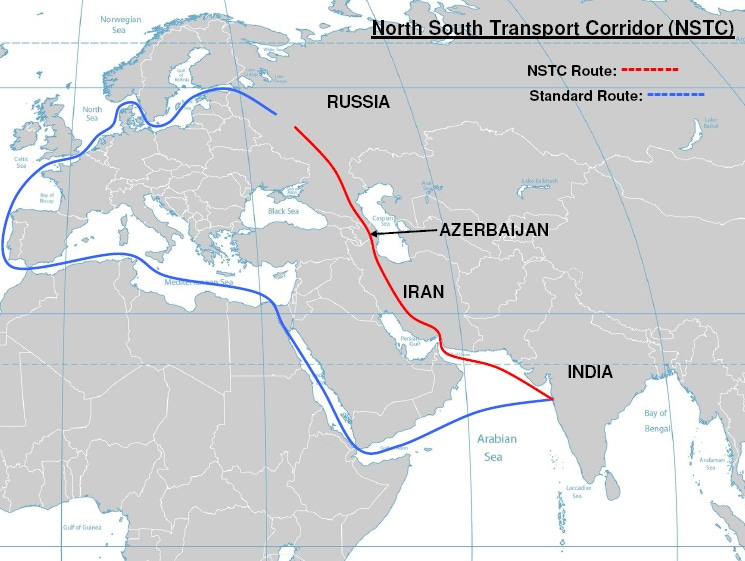

The Persian Gulf-Black Sea International North-South Transport Corridor is already up and running. It goes from Iran’s Gulf ports to Armenia and Georgia, over the Black Sea to Bulgaria, and overland into northern Europe. Cargo from northern Europe and Russia began flowing into India via this corridor a couple of months ago. The corridor is now emerging as the most efficient alternative to the sea route from the North Sea to Asia.

China has other rail corridors in place. One goes from Inner Mongolia to Tehran. Another proposed railway line links Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan to the Iranian port of Chabahar, in which India, too, has an interest. Chabahar is a free-trade zone, so neither the port nor freight that passes through it is subject to US sanctions.

China is financing a new rail link between Chabahar and Zahedan, in Iran’s Sistan province, offering another connection to the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in neighboring Balochistan. A Qom-Eshfahan-Tehran railway project linking three of Iran’s most important cities, and possibly Kazakhstan, is also being planned. This, too, is financed by China.

The connection between the INSTC and these new rail links gives Iran a tremendous leg up. It connects Iran to Europe, Central Asia, and South Asia in a seamless overland route that has several advantages over traditional sea routes. Iran has been expecting Russia to invest in the Rasht-Astara railway line that it needs to complete a link to Azerbaijan. But if that’s not forthcoming, China stands ready to bridge the gap.

Will Beijing succeed?

The future of Central Asia looks like a vast spiderweb of rail corridors, mostly built with Beijing’s money. But as recent developments in Africa show, infrastructure investments like roads, railways, and telecom might not be enough to create strong regional or national economies. To be profitable, trade and people must flow across roads and railway lines. Telecom needs data and calls.

Take, for instance, Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway, built with Chinese money, which connects Nairobi to Mombasa. Its losses over a three-year period are now more than US$200 million. It faces suspension and closure.

Recently, Zambia proactively canceled US$1.6 billion in Chinese loans, most of which had been earmarked for fourteen road and telecom projects. It had no means to repay them. The largest was for a US$1.2 billion highway between Lusaka and Zambia’s copper belt.

The Central Asian nations and Iran are primarily exporters of commodities such as minerals, or oil and gas, whose prices are set on the global market. Neither China nor any of the countries in the region have much control over commodity pricing.

To fully absorb the debt that comes with this infrastructure, the countries of the region will have to move up the value chain to manufacture and export goods beyond commodities—perhaps derivatives of these commodities, like petrochemicals and fertilizers from oil and gas. This can only happen if the investment is made downstream.

Foreign investment leads to growth, says the theory. But investment in infrastructure alone doesn’t. Infrastructure facilitates growth, but it’s not a multiplier. That requires investment in industry, and China’s track record suggests little willingness to invest in greenfield manufacturing or service industries. It hasn’t in Africa. It might not in Central Asia or Iran.

The BRI infrastructure investment promises financial capital and investment in basic industries like mining. It doesn’t enhance the recipient country’s technological prowess, allowing it to move up the industry’s value chain. It doesn’t necessarily transfer managerial and technical know-how, because China tends to use Chinese personnel to build and manage projects.

Without finance, technology and the transfer of skills to build downstream industries, and without high employment and savings, recipients of China’s BRI largesse will remain at the periphery, with China at the core.

In 2019, Xi hinted that China knew there was a flaw in the plan. “China does not pursue a trade surplus intentionally,” he said. “It would like to import more … products and services.” But China hasn’t altered its BRI model. Recipient countries remain a captive export market for China’s value-added goods, but they’re still exporting raw commodities while importing these value-added products. This results in trade deficits, trade traps, and massive unserviceable debt.

So China’s gambit to reshape the world through its investments in Central Asia and Iran has a long way to go.

We’ll see about Xi’s wisdom.

Vivek Y. Kelkar is the co-founder of the Cosmopolitan Globalist

Building railroads that could connect China to Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe sounds like a fine idea. A reliable land route would probably reduce reliance on sea-borne freight snd overburdened mega-ports, not to mention an implied reliance on the US Navy as the world's ocean-going policeman keeping international waters safe and secure from piracy. On the other hand, and there is usually an "other hand" wagging a cautionary finger at such schemes, rail freight necessarily must cross national boundaries, while ocean freight need not. I assume that securing its supply routes is a major factor driving China's BRI, and not simply fostering dependent relationships with less affluent nations, the fear being, what happens to China if the US were to apply sanctions to it? Should relations between China and its debtors deteriorate, rail freight could be interrupted fairly easily, whereas applying sanctions to ocean freight is complicated and resource-intensive.