This is the third part of what is now a four-part series. (I spent two days trying to compress the final part into a single newsletter, then gave it up as a bad job.)

Note for those only now tuning in: We’ve been discussing a video in which the geopolitical analyst Peter Zeihan predicts, among other things, China’s collapse within the coming decade, the world’s imminent deglobalization, and an attendant economic catastrophe so significant that billions of people in the developing world will perish of famine. Here are the earlier parts of the discussion:

I also wrote about Peter Zeihan in an earlier instantiation of this newsletter:

If you’re really impatient, here’s my answer: Yes, I do think he’s on the right track. I don’t necessarily think he’s right, but the points he raises are both interesting and insufficiently appreciated.

Can we predict the future?

One of the most interesting questions he raises, if obliquely, is whether it is possible to predict the future at all.

Let’s stipulate from the outset that Zeihan’s tone of serene confidence in his predictions is completely unwarranted. If I were asked to place money on the proposition that the future will unfold exactly as he predicts, I wouldn’t hazard a single penny. This is obvious, but there’s a reason to say this explicitly.

It’s not a criticism. Zeihan isn’t writing a finished intelligence report for policymakers; he’s writing books and making videos for our edification and entertainment. No one would buy a book written in the manner of a finished intelligence report, a point I can easily demonstrate.

The quadrennial Global Trends report is produced by the National Intelligence Council, the bridge between the American intelligence community and policy makers. The Council works with the National Security Agency, CIA, and the other sixteen organs of the US intelligence community to prepare the report, so it has access to an enormous amount of carefully vetted information. It also draws on academic expertise, think tanks, universities, consultants, independent researchers, and the private sector.

Every four years, the final draft of Global Trends is reviewed by the incoming Director of National Intelligence and placed on the incoming president’s desk ahead of Inauguration Day. In principle, the report is independent of US policy. It’s not designed to suggest or affirm any policy or plan of action. Does this mean it’s free of political influence? Of course not, because man is a political animal, but to the extent it is, it’s unconscious. It’s meant to be, and it’s presented as, a strictly analytic product.

The seventh edition of the report, Global Trends 2040: A More Contested World, was released in 2021. Clocking in at 140 pages, the report treats global demographic, environmental, technological, political, and economic trends, just as Zeihan does, and in the most important way, the Council is in broad agreement with him: The future will be terrible.

No one ever sends me emails asking me what I think about it. Not because it’s classified—it’s not. It’s been released to the public, it’s free, and it’s online. But no one’s read it. Because no one wants to read a book written in the manner of a finished intelligence report.2

One reason Zeihan’s books are more popular is that Zeihan throws out the whole apparatus of probability in favor of a trait people like much more: confidence. He’s placed his bets. This is the way it will be. Not might be or could be. It will be. The more confidently he says this, the better his books sell. Again, not a criticism, just an observation.

If Zeihan were writing a finished intelligence report, he’d be obliged to use what intelligence analysts call “words of estimative probability.” The phrase comes the celebrated CIA analyst Sherman Kent, the so-called father of intelligence analysis. Kent was dismayed by problems like this: In 1960, a special committee of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, led by Brigadier General David W. Gray, told JFK that the attack on the Bay of Pigs had “a fair chance of ultimate success.” General Gray later said, “We thought other people would think that ‘a fair chance’ would mean, ‘not too good.’”

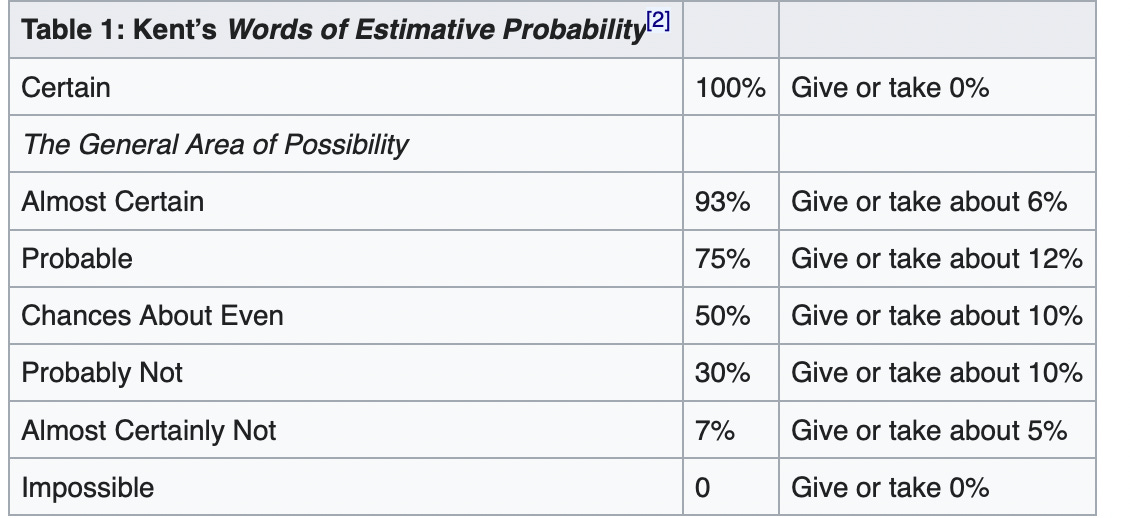

Thus, in 1964, Kent wrote a memo titled, “Words of Estimative Probability.” It's now declassified and you can read it online in the National Archives.3 Kent insisted not merely that claims about the future be accompanied by words of estimative probability—certain, almost certain, probable, etc.—but that these words be translated into numeric odds, and these, he said, should be standardized across the intelligence community.

“There is a language for odds,” he wrote, “in fact there are two—the precise mathematical language of the actuary or the race track bookie and a less precise though useful verbal equivalent.” Intelligence estimates, he wrote,

… should set forth the community’s findings in such a way as to make clear to the reader what is certain knowledge and what is reasoned judgment, and within this large realm of judgment what varying degrees of certitude lie behind each key statement. Ideally, once the community has made up its mind in this matter, it should be able to choose a word or a phrase which quite accurately describes the degree of its certainty; and ideally, exactly this message should get through to the reader.· [My emphasis—all emphasis in the quoted texts from now on is mine.]

I’m copying passages of the memo to entice you to read it. (You don’t have to, it’s not essential to the story—it’s just interesting.)

Since then, intelligence reports have couched their claims in the language of probability and confidence, with each part of claim assessed separately and given its own confidence ranking. Any serious geopolitical forecast is necessarily probabilistic and will involve this approach, because our understanding of the world is far too incomplete for it to be otherwise.

Assessing the parts of the claim separately is especially important. It’s no good saying you’re almost certain China will starve if its population collapses unless you specify your confidence in the proposition that China’s population will collapse. This kind of language makes it easier for readers to distinguish all the steps in the inferential chain and figure out what we actually know and what’s just a hunch. But it’s not anywhere near as lively to read.

One thing I should stress: Words of estimative probability are just a tool for communicating more clearly. They’re not true assessments of probability. When we’re talking about geopolitical predictions of the sort Zeihan or the Council are making, true probability assessments would be nonsensical. How would we even come up with them? We can test the theory, for example, that the odds of fair coin coming up heads are one in two, but it’s impossible empirically to test the theory that Americans will in the coming decade pack it up and leave the sea lanes to police themselves. It’s not as if we can run a massive simulation of the whole world, over and over, to see what happens.4

Consider the following three statements:

If you throw Xi Jinping into the air, he will fall.

If you’re an 18-year-old Chinese citizen, your odds of being unemployed this year are 4.66 percent.

There is a 63 percent chance that the Chinese government will collapse in the next decade.

The first statement is deterministic. The second is probabilistic. The third is nonsensical. It’s using probabilistic language, but of course there’s no way anyone can be certain that these are really the odds.5 We cannot make accurate probabilistic estimates of the likelihood of China collapsing before 2030 the way we can about the likelihood of the Brooklyn bridge collapsing before dinnertime. Or rather, we can, but we don’t mean them literally. Or if we do, we’re grievously overestimating our aptitudes.

Forecasting works, in the right domains: simple systems, short time horizons. Complex systems, over a long time? No. Complex systems are highly sensitive to initial conditions—the Butterfly Effect—and the more complex the system, the less predictable it is. Our confidence in any prediction we make about a complex system must necessarily be low, and the further ahead we try to predict, the lower our confidence must be. It’s literally impossible to predict, with precision and confidence, the future of a system as complex as the entire world over a time period of two decades. No one has ever done it and no one will.6 None of us are even capable of forecasting the headline news one week from today.7 Obviously, we’re not up to the job of forecasting the future of the world in twenty years.

When we try to forecast the future, we’re really trying to describe a plausible world given these initial conditions. So my impression of Zeihan can be positive even if I’m not sure he’s right: He’s sketching out a plausible future world, and he’s raising arguments to which I hadn’t given sufficient thought.

If this seems like weak praise, it isn’t. Most people’s theories about the way the world will be in twenty years are ludicrous, and the more detailed the prediction, the more points of plausibility failure there are.

Zeihan’s future is only one plausible future among many plausible futures. Some of those futures might be better, some might be worse—much worse.8 His scenario is more plausible than quite a number that people waste time worrying about. I’m glad he’s not only showing how plausible this scenario is, but doing it in a way so entertaining and accessible that people send me emails asking about it. This may even make it less plausible, if he convinces enough Americans that this is a really bad future that we want to avoid.9

It’s instructive to compare Zeihan’s predictions with those of the Global Trends report, which I’ll use as a stand-in for “the orthodox, consensus forecast.” The Council is not in the business of entertaining anyone, so I’ve read it for you. (That’s worth the price of a subscription, surely.)

Global Trends: 2040 has three sections. The first treats what the authors term structural trends, by which they mean demographics, the environment, economics, and technology. These are topics about which they can offer projections, they write, “with a reasonable degree of confidence based on available data and evidence.”

The next treats the intersection of structural trends and human beings, at three levels: first, individuals and society; second, the state; and third, the international system. Analyzing these intersections, they allow, “involves a higher degree of uncertainty because of the variability of human choices that will be made in the future.” Right. People are involved, and we can never say what that deranged mob of unlettered lunatics will do.

The third section identifies key uncertainties. (Zeihan’s books feature no such section.) They use these to create five plausible scenarios for the world in 2040, and sketch them out in some detail.

The report is a dull but respectable effort. They’re honest about what they don’t know. I reject some aspects of their scenarios as implausible, but find the others reasonably plausible. One of them has quite a bit of overlap with Zeihan’s.

Like Zeihan, the Council stresses the world’s changing demography. They largely agree with him about the trends. But their language becomes progressively less confident as they consider the second- and third-order effects of these trends; i.e., yes, the world is aging (for sure); and this could be catastrophic (probable); on the other hand, people may be able to mitigate these effects (maybe). We just don’t know. So they write:

The most certain trends during the next 20 years will be major demographic shifts as global population growth slows and the world rapidly ages.10 Some developed and emerging economies, including in Europe and East Asia, will grow older faster and face contracting populations, weighing on economic growth. In contrast, some developing countries in Latin America, South Asia, and the Middle East and North Africa benefit from larger working-age populations, offering opportunities for a demographic dividend if coupled with improvements in infrastructure and skills. …

They judge this unlikely, however, because “the next levels of development are more difficult and face headwinds from the Covid19 pandemic, potentially slower global economic growth, aging populations, and the effects of conflict and climate.”

Their views about the effects of climate change are similar to Zeihan’s. They see the burden falling disproportionately on the developing world. (That’s an easy call.) What about the global economy? Some of their points are similar to Zeihan’s:

During the next two decades, several global economic trends, including rising national debt, a more complex and fragmented trading environment, a shift in trade, and new employment disruptions are likely to shape conditions within and between states. Many governments may find they have reduced flexibility as they navigate greater debt burdens, diverse trading rules, and a broader array of powerful state and corporate actors exerting influence.

But they’re not as bearish on globalization:

Large platform corporations—which provide online markets for large numbers of buyers and seller—could drive continued trade globalization and help smaller firms grow and gain access to international markets. These powerful firms are likely to try to exert influence in political and social arenas, efforts that may lead governments to impose new restrictions. … Productivity growth remains a key variable; an increase in the rate of growth could alleviate many economic, human development, and other challenges.

They don’t seem concerned that pirates and brigands will drive up the cost of insurance, bringing globalization to an end. And they’ve introduced several variables that Zeihan doesn’t treat adequately, among them, productivity growth. As they point out—and I agree—technological change could shape the future in ways we don’t now understand:

Technologies are being invented, used, spread, and then discarded at ever increasing speeds around the world, and new centers of innovation are emerging. During the next two decades, the pace and reach of technological developments are likely to increase ever faster, transforming a range of human experiences and capabilities while also creating new tensions and disruptions within and between societies, industries, and states. State and nonstate rivals will vie for leadership and dominance in science and technology with potentially cascading risks and implications for economic, military, and societal security.

As for the interaction of these trends with people, they look at this more broadly than Zeihan does. Zeihan says little about politics. The Council is quite concerned about the way things are headed, though:

Within societies, there is increasing fragmentation and contestation over economic, cultural, and political issues. Decades of steady gains in prosperity and other aspects of human development have improved lives in every region and raised peoples’ expectations for a better future. As these trends plateau and combine with rapid social and technological changes, large segments of the global population are becoming wary of institutions and governments that they see as unwilling or unable to address their needs. People are gravitating to familiar and like-minded groups for community and security, including ethnic, religious, and cultural identities as well as groupings around interests and causes, such as environmentalism. The combination of newly prominent and diverse identity allegiances and a more siloed information environment is exposing and aggravating fault lines within states, undermining civic nationalism, and increasing volatility.

The Council envisions a widening gap between what publics want and what governments can provide:

This widening gap portends more political volatility, erosion of democracy, and expanding roles for alternative providers of governance. Over time, these dynamics might open the door to more significant shifts in how people govern.

As for the international system? They largely agree with Zeihan, save in their evaluation of China’s future:

In the international system, no single state is likely to be positioned to dominate across all regions or domains, and a broader range of actors will compete to shape the international system and achieve narrower goals. Accelerating shifts in military power, demographics, economic growth, environmental conditions, and technology, as well as hardening divisions over governance models, are likely to further ratchet up competition between China and a Western coalition led by the United States. Rival powers will jockey to shape global norms, rules, and institutions, while regional powers and nonstate actors may exert more influence and lead on issues left unattended by the major powers. These highly varied interactions are likely to produce a more conflict-prone and volatile geopolitical environment, undermine global multilateralism, and broaden the mismatch between transnational challenges and institutional arrangements to tackle them.

So in broad brush, they agree with Zeihan. Ahead of us lies chaos, poverty, conflict, misery, the decline of globalization, and a world divided into regional blocs led by local hegemons. The good times are over and Queen Elizabeth’s reign was the best it will be.

Much of the world, they write,

will struggle to build on or even sustain the human development successes achieved in the past several decades because of setbacks from the ongoing global pandemic, slower global economic growth, the effects of conflict and climate, and more difficult steps required to meet higher development goals. Meanwhile, countries with aging populations and those with youthful and growing populations will each face unique sets of challenges associated with those demographics.

The prospect that most worries Zeihan is the effect of deglobalization on supply chains, particularly the ones the world needs to feed itself, and he sees the “unique set of challenges” associated with China’s demographics as “total collapse.” The Council seems more worried about China’s “growing disrespect for international order,” Russian aggression and expansionism, swelling national debts, cyberwarfare, mass surveillance, declining freedom and democracy, technological competition, and artificial intelligence.

Either way—it’s not good.

The Council’s assessment of global demographic trends is slightly less dire than Zeihan’s. The difference is interesting, first, because this is the part about which forecasters should be confident, but clearly we’re not, and second because it demonstrates the principle that complex systems are highly sensitive to initial conditions: If you begin trying to figure out what the world will look like in twenty years using slightly different numbers, you end up in a very different place.

The Council predicts that most developed and a handful of emerging economies will see their populations peak and then start to shrink before 2040. Sub-Saharan Africa will account for two-thirds of global population growth. They’re in agreement with Zeihan that senescent countries are in trouble, but because their numbers are slightly different, they’re less persuaded that this is a terminal problem. Instead, they see an unpleasant choice ahead, at least among the G20: cutting benefits for the elderly or increasing taxes. This may put major stress on existing political arrangements, they say. (Or as Zeihan might put it, this dooms democracy.)

Like Zeihan, they envision an Africa that hasn’t the infrastructure, governance or educational capacity to cope with deglobalization. (They don’t call it “deglobalization.” But they certainly see “interruptions in patterns of trade.”) Like Zeihan, they’re worried this will end very badly for Africa.

From these assumptions, they conclude that all of the following scenarios are plausible:

Renaissance of Democracies. The world is in the midst of a resurgence of open democracies led by the United States and its allies. Rapid technological advancements fostered by public-private partnerships in the United States and other democratic societies are transforming the global economy, raising incomes, and improving the quality of life for millions around the globe. The rising tide of economic growth and technological achievement enables responses to global challenges, eases societal divisions, and renews public trust in democratic institutions. In contrast, years of increasing societal controls and monitoring in China and Russia have stifled innovation as leading scientists and entrepreneurs have sought asylum in the United States and Europe.

A World Adrift. The international system is directionless, chaotic, and volatile as international rules and institutions are largely ignored by major powers like China, regional players, and nonstate actors. OECD countries are plagued by slower economic growth, widening societal divisions, and political paralysis. China takes advantage of the West’s troubles to expand its international influence, especially in Asia, but Beijing lacks the will and military might to take on global leadership, leaving many global challenges, such as climate change and instability in developing countries, largely unaddressed.

Competitive Coexistence. The United States and China have prioritized economic growth and restored a robust trading relationship, but this economic interdependence exists alongside competition over political influence, governance models, technological dominance, and strategic advantage. The risk of major war is low, and international cooperation and technological innovation make global problems manageable over the near term for advanced economies, but longer term climate challenges remain.

Separate Silos. The world is fragmented into several economic and security blocs of varying size and strength, centered on the United States, China, the European Union, Russia, and a couple of regional powers; these blocs are focused on self-sufficiency, resiliency, and defense. Information flows within separate cyber-sovereign enclaves, supply chains are reoriented, and international trade is disrupted. Vulnerable developing countries are caught in the middle with some on the verge of becoming failed states. Global problems, notably climate change, are spottily addressed, if at all.

Tragedy and Mobilization. A global coalition, led by the EU and China working with nongovernmental organizations and revitalized multilateral institutions, is implementing far-reaching changes designed to address climate change, resource depletion, and poverty following a global food catastrophe caused by climate events and environmental degradation. Richer countries shift to help poorer ones manage the crisis and then transition to low carbon economies through broad aid programs and transfers of advanced energy technologies, recognizing how rapidly these global challenges spread across borders.

Zeihan’s future is quite like the one in “Separate Silos.” What they don’t see as plausible is as interesting as what they do: Do you see “war between the US and China” on that list?

Which scenario do you find most plausible, and why? (Read the whole scenario, to be fair.)

China and America

The Council disagrees significantly with Zeihan in two respects. First, it doesn’t foresee China’s collapse. (Nor does anyone else—Zeihan’s claim here is wildly heterodoxical, and if he’s right, he’ll be able to dine out on it forever.) Nor does it foresee the United States’ withdrawal from the world.

Why do they disagree about China’s resilience? Strangely, it’s hard to tell. They seem more or less to agree with Zeihan about the raw facts of China’s demography, and you would think that from there, it’s just arithmetic. But neither Zeihan nor the Council have footnoted their claims carefully enough for me to be able to figure out exactly why they diverge. Are they looking at different numbers? Are they adding their numbers correctly? Or do they think the same numbers imply something very different, economically?

The Council agrees that China’s population is extremely old. They agree its population has peaked, or they must, because they see India surpassing China in population in 2027. “The deep decline in fertility from [China’s] one-child policy,” the Council writes,

has already halted the growth of its labor force and will saddle it with a doubling of its population over 65 during the next two decades to nearly 350 million, the largest by far of any country. Even if the Chinese workforce is able to rise closer to advanced-economy productivity levels through improved training and automation, China remains in danger of hitting a middle-income trap by the 2030s, which may challenge domestic stability.

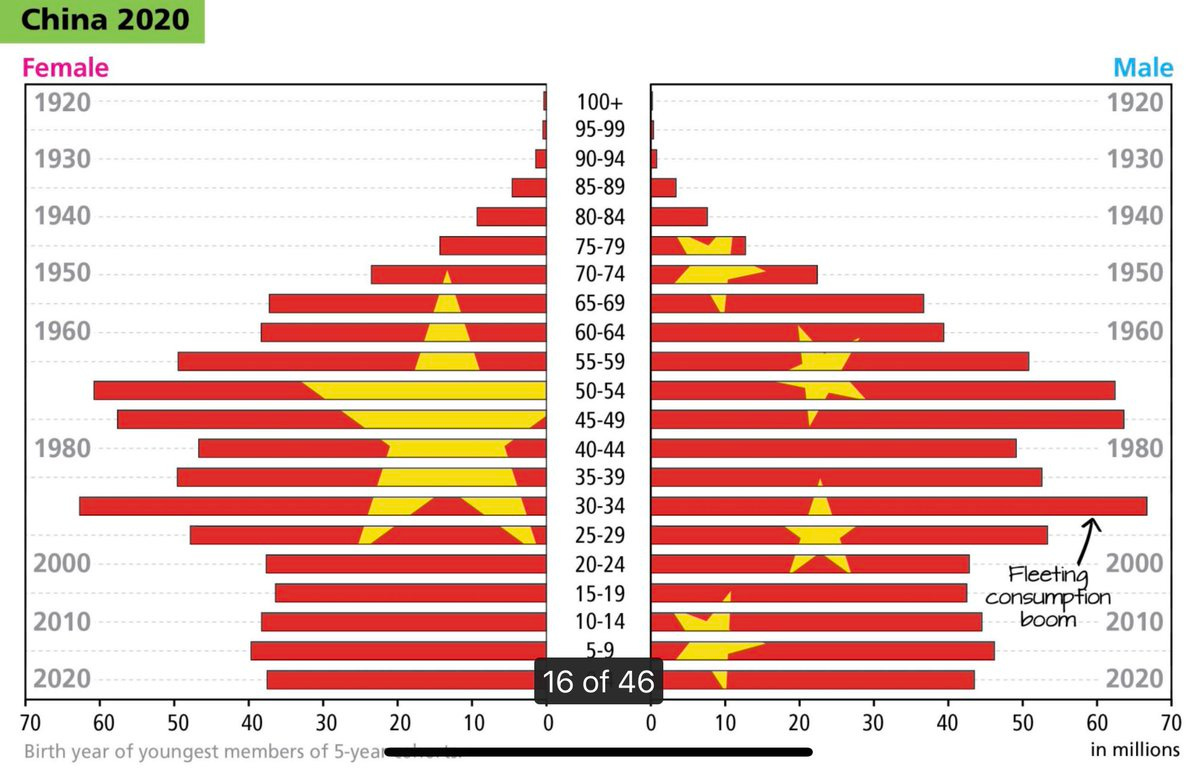

But what of the raw numbers? Here’s Zeihan’s China 2020 population chart:

Global Trends doesn’t have a China 2020 chart, but it has a Northeast Asia 2020 chart, based on statistics from the UN Population Division and Oxford Economics:

China is by far the largest country in northeast Asia. The other countries in northeast Asia have similar demographics, so I’d guess this probably looks a lot like their China chart. In any event, their chart tells the same story as Zeihan’s chart: There’s a bulge in the middle, meaning many will soon retire and there aren’t a lot of kids to replace them. In both, there are more men than women.11

But Zeihan believes China has by far the fastest-aging population in the world. The Council doesn’t. Or at least, it doesn’t foresee China losing its working age population as quickly as South Korea, Japan, and much of Europe. In the coming two decades, the Council writes,

South Korea is projected to lose 23 percent of its working-age population (age 15-64), Japan 19 percent, southern Europe 17 percent, Germany 13 percent, and China 11 percent … if the retirement age remains unchanged.

China has one of the youngest retirement ages in the world—60—so that can’t be the reason for the difference. So I suppose Zeihan and the Council must be looking at different sets of numbers. Not wildly different, but different. Zeihan may be looking at more recent figures, or he may distrust Chinese figures more than the Council does.12 Everything else in their assessments hinges on these numbers. But without looking at their data sets, I just can’t say who’s wrong.

Still, it’s mysterious. Zeihan and the Council don’t disagree in some massive way about the structure of China’s population. Nor do they disagree about the general effect a senescent population structure has on an economy; to wit, a bad one. But where Zeihan sees China collapsing and its population starving, the Council sees China becoming the United States’ most significant rival:

The growing contest between China and the United States and its close allies is likely to have the broadest and deepest impact on global dynamics, including global trade and information flows, the pace and direction of technological change, the likelihood and outcome of interstate conflicts, and environmental sustainability. Even under the most modest estimates, Beijing is poised to continue to make military, economic, and technological advancements that shift the geopolitical balance, particularly in Asia.

The Council sees an ascendent China, not a collapsing one:

In the next two decades, China almost certainly will look to assert dominance in Asia and greater influence globally, while trying to avoid what it views as excessive liabilities in strategically marginal regions. ... China is likely to field military capabilities that put US and allied forces in the region at heightened risk and to press US allies and partners to restrict US basing access. Beijing probably will tout the benefits of engagement while warning of severe consequences of defiance. China’s leaders almost certainly expect Taiwan to move closer to reunification by 2040.

They can’t both be right.

Might the difference devolve from the Council’s estimation of the likelihood that China can mitigate the impact of its senescence? Zeihan and the Council both observe that when populations age, the party’s over—as a rule. Writes the Council:

During the next two decades, the [global] middle class is unlikely to grow at a similar pace, and developing-country middle-income cohorts could well perceive that their progress is slowing. Across many countries, the high per capita income growth of the past 20 years is unlikely to be repeated, as global productivity growth falls and the working-age population boom ends in most regions.

But the Council mostly foresees economic stagnation as a consequence, not the starvation of billions.13

Global models of household income suggest that, under a baseline scenario, the middle class share of the global population will largely remain stable during the next twenty years, although this outcome will be contingent on social and political dynamics.

This is perhaps because Zeihan sees no way to mitigate the effects of aging, whereas the Council believes it may be mitigated by “adaptive strategies,” such as automation and increased immigration. Around the world, the Council writes,

Demographics, specifically aging populations, will promote faster adoption of automation, even with increases in the retirement age. … Automation—traditional industrial robots and AI-powered task automation—almost certainly will spread quickly as companies look for ways to replace and augment aging workforces in these economies.

So will China collapse, or will it rule the world? It all depends whose numbers are right and whether China can replace its youth with droids.

The Council also points out that in one important respect, an aging population is not a bad thing: “Older populations tend to be less violent and ideologically extreme, thus reducing the risk of internal armed conflict.”

As for the United States, the Council doesn’t even hint at the possibility it will withdraw precipitously from the globe’s crucial maritime arteries and leave them to the mercy of pirates. This seems significant. In principle, they’d be the first to know if this was about to happen. It’s possible, I suppose, that this is why they don’t see China collapsing—perhaps that only happens, in the Zeihan scenario, if the US ceases to protect global shipping.

All the same, the Council’s view of the future is just as gloomy as Zeihan’s—ignoring the happy-talk first scenario, which I expect they felt compelled to include because Americans believe in the power of positive thinking. It will be a chaotic, violent world. The future is dark. Zeihan is 100 percent sure of it and the Council thinks it’s probable, give or take about 12 percent.

Time to put my cards on the table. In the next and final newsletter, I’ll argue that Zeihan’s understanding of the postwar order—or as he calls it, the Order—is ahistoric. It didn’t emerge the way he says, and it didn’t happen for the reasons he thinks.14 Consequently, his estimation of the odds that the United States will now abandon the Order are too high.15

But I don’t think he’s entirely wrong. I think it’s a real and very grave risk. I’d put it somewhere between “probably not” and “even.” That said, if it did happen, it would probably only be partial, and even if it were complete, the odds that globalization would survive, in some form, are not zero. I’d put those odds somewhere around “probably.”

But the risk that Zeihan is right is so real that I’ll say what Zeihan refrains from saying. We can’t let that happen. It would be a God-awful catastrophe. Fortunately, whether or not it happens is not a function of the bad choices in presidents we’ve made since 1992. All the critical choosing still lies ahead of us.

Or unfortunately. We’ll see.

All in all, though, I think he’s probably wrong.

I changed the headline to improve the SEO. Most of you have read that already.

cf. this US Peace Institute video about the Global Trends 2040 report. A duller and more dreary collection of pallid bureaucratic time-servers is hard to imagine.

It’s an interesting document for historians, but it will also be interesting to linguists. Anyone who did archival research before the Internet knows what I mean when I say it is amazing that these documents can now be read online, for free, and from the comfort of your couch. I had to fly to Washington and search for memos like these in massive physical boxes of physical papers in a huge building we called a library, which was only open for about eight hours a day. Sometimes the only clue you had about what was in the box was the author’s name and a date. Sometimes you didn’t even get a date. You had to decide on the spot whether you ever wanted to see that document again, and if so, photocopy it. And then haul all of the photocopies back over the Atlantic in a suitcase. We lived like primitives, I’m telling you—barely better than apes. Now, you can casually skim through reams of secret American government papers and find out stuff that no one’s even heard about before, and you can do it for free, while the rest of America drives itself nuts trying to decipher the latest Q drop.

Some try to do this, yes, but the simulations are primitive—there’s a major map-versus terrain problem.

I’ve rushed this, but if these points are at all unclear, Jim Manzi’s book Uncontrolled has a terrific description of the difference among these statements and why they matter.

Maybe I shouldn’t be so confident. I was equally dubious about the prospects for machine translation, but here we are. Let’s just say it is highly unlikely that we ever will.

If you think you are, now's your chance to prove it. Put it in the comments.

Like so, for example. Alas, those too are plausible world, and more plausible than people think.

That’s another reason we can’t make precise forecasts about the future. The act of doing so changes that future.

My emphasis—all the bold type in the citations is mine.

Sentence corrected: I originally wrote, “more men than women.” Of course it’s the other way around. Thank you, Geoff Marcy!

I’ve been scouring both reports for days, trying to find the clue. Maybe an eagle-eyed reader sees something I’ve missed?

It allows for that possibility, though. It’s one of its scenarios.

Solid terrain, at last. I’m much more confident talking about the past than the future.

I’m assigning to him probabilistic language he doesn’t use. He says the United States will abandon its traditional role as the guarantor of maritime security—in other words, that the odds are 100 percent

Regarding the comment "The good times are over and Queen Elizabeth’s reign was the best it will be."

Churchill, as usual, said it best in the coronation speech: ‘That it should be a golden age of art and letters we can only hope but it is certain that if a true and lasting peace can be achieved … an immense and undreamed-of prosperity, with culture and leisure even more widely spread can come … to the masses of the people.’

We are immeasurably lucky indeed to have lived in the second Elizabethan Era.

IMO, the question about any long-term forecaster is not whether they are ultimately right - as conclusions are dependent upon many intermediate steps/events and policy makers have time to adjust to new events as they happen, but whether they highlight risks/possibilities one has not considered or weighted highly enough. Decision-makers like to hear from people who think differently (and make them think differently), even if our ultimate forecasts (several steps down the road) will diverge.

Thought processes and insights are often more useful than the ultimate forecast- or at least more likely to be of value as the odds of a long-term forecast being exactly correct is remote.