The Apocalyptic Magisterium

When we think about catastrophic risks, we are prone to grave cognitive mishaps.

Some time ago, having noticed on Twitter my interest in global catastrophic risks, a research professor at the Astronomical Observatory of Belgrade named Milan M. Ćirković sent me a copy of a book he had edited together with Nick Bostrom, the founding director of Oxford’s Future of Humanity Institute, titled Global Catastrophic Risks. Its twenty-two chapters treat almost as many risks, including some that had never occurred to me.

Ćirković and Bostrom define a global catastrophe as one that causes ten million deaths or US$10 trillion in damages. It is difficult to offer a precise appraisal of the odds of such catastrophes, but many of these scenarios are more likely than we’d prefer to think. Indeed, we’d prefer not to think about them at all. When we’re forced to do so, we think about them in an irrational way.

We’re highly prone to a particular set of cognitive biases when we think about these kinds of risks. Some are biases that afflict us in thinking about many other problems. Some are particular to the way we think about catastrophes. Together, they amount to a near-blinding set of obstacles to rational thought. This is a problem, because these scenarios are fully plausible, whether we prefer to think about them or not.

At this point, one of my readers will say, “Come on, Claire. People have been warning the end of the world is nigh since forever, but we’re still here.” Is that you? You, in the back of the class? Yeah, that’s a cognitive error—survivorship bias, to be precise. Catastrophic risk isn’t a function of the number of people who’ve warned of it in the past and been wrong. It’s a function of the size of the asteroid en route toward your noggin.

Some catastrophic risks (annihilation by asteroid, for example) are neither more nor less probable than they were a million years ago. But the 21st century is, in reality, more dangerous to our species than any previous century. Why? Because of the pace of technological change. Unless we get serious and work diligently to mitigate these risks, this is apt to be a century of catastrophes. We could well wipe ourselves out completely. It’s irrational to think otherwise.

People who have never given the matter serious thought tend to underball these risks. How do you think you’re more likely to die: in a car crash, or an extinction event? You chose “car crash,” right? (Except those of you who figured, “It’s obviously a trick question” and tried to game it.) But no, you’re probably wrong.

It’s very difficult—impossible, really—robustly to compute the risk of the extinction of humanity in the coming century. But existential risk has become the object of an emerging field of scientifically serious study. Almost everyone who studies these problems rigorously figures you’re more likely to die in an extinction event.1 While experts aren’t infallible, generally the people who think carefully about a problem—any problem—are more likely to be right than the people who never think about it. The people who never think about it tend to figure the risk of human extinction in the coming century is quite low. When asked to guess the odds, for example, more than 30 percent of Americans estimated they were below one in ten million.

They’re probably wrong.

The literature on extinction-level risks in the coming century converges on an annual risk of .01 to 0.2 percent. Let’s say this is right. It’s probably the right order of magnitude, at least. Low but not negligible. Small annual probabilities compound significantly over the long term, so this means the chance of human extinction in the next century is 9.5 percent. If this is right, you’re more likely to die from an event that annihilates the entire human race than you are to die in a car crash.

How many of you responded to that argument by dismissing it? Did you do it before you thought it through? Why?

Denial is only one of the many severe cognitive biases to which we’re prone when thinking about catastrophic risk. We’re only a fifth of the way into this century and we’ve already got one catastrophe our belt. Another one is highly likely, if not inevitable, unless we start thinking straight and do something about it.

But our deep aversion to thinking about these risks, and the mistakes in reasoning we tend to make when we try, make us far less likely to mitigate them effectively. The human tendency to think poorly about catastrophic risk is, itself, a source of catastrophic risk.

Like many of the other risks we confront, it can be mitigated. By understanding and recognizing our errors in cognition and teaching ourselves to think more rigorously, we can improve our odds.

We are all prone to these biases. They’re part of human nature. I’m hardly immune—despite years of thinking not only about catastrophic risks but about the biases that prevent us from recognizing and mitigating them, I was blindsided by Covid19. Just didn’t see it coming. I asked myself why in these essays, parts of which I’ll reprise below:

Why didn’t I see the Covid catastrophe coming? Reflections on cognitive bias, punditry, and accountability

Should pundits who missed the pandemic be fired? I didn’t warn you about Covid in time. Is that grounds for my resignation?

Let’s posit an imaginary rational society. It is not yours, of course, and it is not anyone else’s either. In this society, politicians and the public regularly and calmly consider these questions:

How much should we worry about events that would be catastrophic if they occurred, but are not likely to occur?

How do we assess these probabilities?

How should we think about catastrophic events that are highly unlikely to occur on any given day, but highly likely to occur in any given decade, century, or millenium?

Can we assess the odds of such catastrophes by asking how often they happened in the past?

What is the best way to mitigate catastrophic risk, both generally and for any given risk?

How much money should we spend to mitigate high-probability catastrophic risks? What about low-probability ones?

At what point does risk mitigation become more costly than the risk it’s meant to mitigate? How do we measure this?

Given limited resources, which are the most important risks to mitigate?

Clearly, because the future of the human race is at stake—not just us, but every possible descendent of mankind for all of time—such a society would prioritize thinking about those questions above thinking, for example, about this:

Are democracies capable of catastrophic risk mitigation? The legitimacy of government, in a democracy, devolves from the consent of the governed. But large majorities of the governed are unwilling or unable to think rationally about catastrophic risk—or any risk, for that matter. So we must not only train ourselves to think more rationally about these risks, but our fellow citizens.

Notice your first reaction to that suggestion.

What happens to us when we contemplate extinction?

The mitigation of catastrophic risks is sometimes simple—using Permissive Action Links to prevent an unauthorized missile launch, for example—but more often difficult. Many such risks, for example, stem from new, dual-use technologies with a global reach. It is difficult to create an enforceable international legal regime to regulate these technologies.

Surprisingly often—you can see this right away if you look at comments on Twitter, say, in response to our essay on the risks of laboratory accidents—this observation prompts people instantly to say that creating such a regime is impossible. Perhaps this word, too, came to your mind when when I suggested we persuade our fellow citizens to think more rationally about risk.

But that’s absurd. Of course it’s possible. The overwhelming majority of human beings on this planet do not want to perish as the result of a lab accident. Even imperfect risk mitigation would be much better than none.

Take a moment to consider how strange the instinct to say it’s impossible really is. You’re used to it, so perhaps it doesn’t immediately seem remarkable to you. But think about it. You would never respond to a grave risk to a member of your family by throwing up your hands, shrugging, and declaring the situation hopeless. Suppose you’d just learned that your child carries the gene for a life-threatening disease. You would read everything, try anything, grasp at any hope, to save him. You would try to raise money for medical research. You would pursue every avenue for international collaboration in the hope of finding a cure. You would convince everyone you knew to take this disease seriously. You would never say it’s impossible—the words wouldn’t even occur to you.

But when confronted with a much bigger threat—a threat not just to one of your children, but to all of them, and of course to you, and to everyone else now alive, and all of their descendents, for all of time, including not only H. sapiens but every species that may descend from us—you throw up your hands? How does that make sense? Logically, a bigger threat should make us more motivated to reduce the risk, not less.

Denial, despair, and shrugging one’s shoulders because nothing can be done are clearly not rational responses. Of course things can be done—many things—and they should be done. Why, when we consider existential catastrophes, do so many of us throw up our hands and say, “It’s hopeless?”

Strange, isn’t it?

Why, too, if we are prone to think of these risks at all, are we prone to fixation on one risk, to the exclusion of others? In the past century, this risk was nuclear war; in this century, climate change. It is perhaps explicable that nuclear war was the cynosure of existential anxieties in the twentieth century. The Bomb was indeed the biggest human-made risk mankind had thus confronted. But that risk hasn’t gone away. Why do people think it has? Why does climate change now occupy our minds to the exclusion of all other risks? That this has happened suggests that the way we think about these risks is something shy of rational.

Why do figures like Greta Thunberg arise? I don’t mean Thunberg herself. She’s not an inherently mysterious phenomenon—she’s a young woman who suffers from severe anxiety, obsessive–compulsive disorder, and a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by restricted, repetitive pattern of behavior and interests. But why on earth has such a figure become—in Time Magazine’s assessment, at least—one of the 100 most influential people in the world? Why would a high school dropout who suffers from emotional and cognitive disabilities that by their nature make her less likely correctly to appraise risk be invited to lecture the Parliament of the United Kingdom—a serious, modern nation-state—about climate change, one of the most complex problems imaginable?

I won’t have trouble persuading my readers that this situation is preposterous, but think how truly bizarre it is. And ask what it suggests. As far as this issue is concerned, the opinion of literally any physical scientist conversant with thermodynamics, computer modelling, and climatology would be more helpful to the Parliament of the United Kingdom than the views of a Swedish high school dropout. Greta Thunberg is prone to saying we must listen to the scientists and newspapers are prone to quoting this approvingly—so why on earth are we listening to her?

Again, this isn’t how people would think, or behave, when confronted with much smaller risks. Imagine a young man—let’s call him Ned—who suffers from Greta Thunberg’s suite of disabilities. Ned is fixated on brain tumors. He reads and commits to memory large chunks of text from the International Journal of Neurosurgery and cannot be dissuaded from doing this. He’s never taken a class in anatomy, no less gone to medical school. Clearly he doesn’t understand very fundamental things—for example, that brain tumors may be deadly but are not always deadly, and the risk of death falls within a range of probabilities, or that the cure might be so costly and painful it could be worse than the disease. If you learned that you had a brain tumor, God forbid, who would you call—Ned? “Ned, this is an emergency—should I have the hippocampal-sparing whole-brain radiation with memantine?”

Of course not. But when people think they have a much bigger problem than a brain tumor—a problem that places the whole living world at risk—Greta Thunberg gets nominated for a Nobel prize three times.

It’s not enough to say, “Well, aren’t people stupid.” Yes, they are. But something in particular happens to people’s brains when they consider catastrophic risk. They get scrambled—instantly. This happens no matter the catastrophic risk they’re contemplating.

At the millennium of the birth of Jesus, Apocalyptic and millenarian sentiment swept popular religious consciousness. “Few Christian teachings,” writes Richard Landes,

more directly concerned and excited the commoners than chiliasm, with its promise of a time of heavenly peace, dreamlike prosperity here on earth, and a justly ferocious punishment for sinners, particularly those who had abused their power by oppressing the poor and defenseless.

According to the best understanding of the world available at the time, humanity faced an imminent existential risk. The eschatological fervor to which this fear and hope gave rise produced a series of popular messiahs uncommonly like Greta Thunberg, and the social reaction to such figures was strikingly similar. Many—including schooled clergy who should have known better—were swept up in the apocalyptic revolutionary movements they led. Others mocked, ridiculed, and denounced them.

Whenever apocalyptic expectations rise, Landes writes,

we find two opposing stances: on the one hand, the apocalyptic enthusiasts, who wax eloquent about the imminent dawn, wishing to wake the believers for the great day; and, on the other hand, the sober antiapocalyptics, who insist that it is still the middle of the night, the foxes are out, the master asleep, and that only damage can come of stirring the population to life before the appointed time.

Authority figures of the eleventh century faced a problem similar to British Parliamentarians. They couldn’t quite bring themselves to denounce the Gretas of their age as noxious little brats with a screw loose (although some did). These eschatological beliefs are, after all, the core of Christianity. This is why people who basically accept the consensus view of anthropogenic climate change have trouble saying, “What are you talking about, you twit.” Then as now, the Establishment had to thread a slender needle: Yes, this theory is partly correct, but—Good grief! This isn’t what we meant.

“As a social phenomenon,” Landes writes,

apocalypticism defies all expectations of fundamentally rational behavior. … apocalyptic believers live in a world of great intensity—semiotically aroused, they see every event as a sign with a specific message for them; emotionally aroused, they feel great love and sympathy for their fellow believers and for all potential converts; physically aroused, they act with great energy and focus; vocationally aroused, they believe that they live at the final cosmic conclusion to the battle between good and evil and that God has a particular role for them. While this belief may be internally consistent, from a larger temporal perspective it is neither rational nor, in most cases, compatible with social stability.

Consider the story of Thiota, a “pseudoprophetess,”

who rather disturbed (“non minime turbaverat”) the city of Mainz in 847 by announcing: “that very year, the Last Day (ultimum diem) would fall. Whence many commoners (plebeii) of both sexes, terror struck, flocked to her, bearing gifts, and offered themselves up to her with their prayers. And what is still worse, men in holy orders, setting aside ecclesiastical doctrine (doctrinas ecclesiasticas postponentes), followed her as if she were a master (magistram) sent from heaven.” Here we have classic apocalyptic millennial dynamics: the prominence of women; the popular response; the defection of clerics who, putting aside their (Augustinian) teachings, entered into apocalyptic time, with its new rules and new roles.

This is a very recognizable description of the Greta phenomenon. And many have seen this parallel:

But what does this mean, exactly? What does it tell us? It does not tell us that there’s no such thing as catastrophic risk and there’s nothing to worry about. But it does tell us that something goes haywire when we think about it.

The Apocalyptic bundle

The sociologist and bioethicist James Hughes describes this phenomenon in an essay titled “Millennial tendencies in response to apocalyptic threats.”2 Millennialism appears to be a universal human belief. Western historians have focused on Christian millennialism, but this set of beliefs is pancultural, found from Europe through Asia, century after century, in Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, and other religions. Eschatological despair—and hope—is one of the most compelling and common themes of popular theology.

Nor is millennialism unique to religious movements. The great historian Norman Cohn drew the connection between Christian millennial movements and revolutionary communism and fascism, and he was right to do so. We might view these secular movements as corrupted species of Christian millenarianism—heresies, in other words; or we could go further and ask whether Christianity itself is a species of an even more instinctive and universal millennialist ur-belief.

Why would millennialism be a universal human instinct? Where might it come from? Hughes offers no deep insight into this question. I have none either. But I’m put in mind of Freud’s observations about the death wish. Our bodies are destined to die just as they are destined to live, Freud remarked, speculating that some aspect of the living organism longs for the peace of death as much as it struggles for life. Perhaps this is also true of whole species. After all, 99.99 percent of the species that have ever walked, flown, or slithered across the Earth are extinct. Is it possible that in some very deep way, we grasp this to be the way of the world, or that in a part of our soul to which we have little conscious access, we long for it? Wherever it comes from, this extinction instinct, we are born with it. And when we contemplate human extinction, the Exstinctio Drive—I just made that term up, do you like it?—colors our reactions.

There is a taxonomy of millennial beliefs, religious and secular. Premillennialists assume the world will descend into horror before the millennial event—a climactic end of history—brings about the messianic kingdom. The obvious example is Christian eschatology based on the Book of Revelations. It is generally a fatalistic worldview. Nothing can and nothing will change the timing of the Tribulation, the Rapture, or the Second Coming. The secular analogue of this belief may be found in the classical Marxist eschatology: Capitalism will immiserate the world until it collapses under its own contradictions, uniting the world’s workers in a global revolution. It’s inevitable; it will happen with or without the aid of a revolutionary vanguard. The idea of the Singularity—the techno-Rapture—constitutes another secular example.

Amillennialists, by contrast, believe the millennial event has already occurred. In Christian terms, these represent teachings of Augustine and the official doctrine of the early Church, which considered premillennialism a heresy. For Augustine, Christians were not awaiting a millennium of perfect peace on earth to come, but rather already living in the invisible millennium—an era of peace and justice unfolding, imperfectly, since the Ascension of Christ. For a secular parallel, think of the fellow travellers who believed Stalin and Mao had successfully ushered in paradise, and soon the rest of the world would follow. Or, say, Francis Fukuyama’s famous essay.

By contrast, the postmillennialist view—dominant among the American Protestants and great reformists of the 19th and 20th century—is not fatalistic. In this view, humans must act to immanentize the eschaton. A similar focus on revolutionary human agency may be found in the Pali canon, and, of course, in revolutionary Marxist-Leninism. Accelerationism is a postmillennialist strain of thought. Such forms of millenarianism are notoriously prone, as Hughes notes, to birthing messianic figures and charismatic revolutionary leaders.

Pay close attention to the way people respond when you mention catastrophic risks. Note how quickly they slip into fatalism—we’re doomed and there’s not a thing we can do about it—before exhibiting even the least bit of curiosity about what might practically be done to diminish the risk. Note how many people who would not respond with a shrug if you told them their family’s safety was at risk are sanguine about the prospect of human extinction—as if the thought satisfies a very deep expectation.

Or a deep sense of what we all deserve.

Hughes locates our inability to think clearly about catastrophic risk in this Apocalyptic bundle. “We may aspire to a purely rational technocratic analysis,” he writes,

calmly balancing the likelihood of futures without disease, hunger, work, or death … against the likelihoods of worlds destroyed by war, plagues, or asteroids, but few will be immune to millenial biases, positive or negative, fatalistic or messianic.

How do these biases manifest? In what Hughes terms the “manic and depressive errors of millennialism”—tendencies to utopian optimism, apocalyptic pessimism, fatalism, and messianism. Thus the helpless shrug—nothing can be done.

It is true that some risks may beyond human powers to remedy. But most catastrophic risks may be mitigated just the way you mitigate any other risk: by being more careful. As Hughes argues, all of these biases—utopian, apocalyptic, fatalist, and messianic—incline us to underestimate the power of ordinary actions and normal political processes to bring about the millennium or prevent apocalypse. Contra the fatalistic bias, ample evidence suggests that changing state policy through normal democratic mechanisms can determine the future. Contra the messianic impulse, it isn’t true that normal democratic mechanisms are too slow and ineffectual to confront problems of heroic magnitude. Efforts to solve them in any other fashion typically deliver violence and authoritarianism, not solutions.

What’s more, the millennial bias gives rise to simplistic and impractical views of the world and how best to make it conform to one’s preferences. Those in its grip, writes Hughes,

tend to reduce the complex socio-moral universe into those who believe in the eschatological worldview and those who do not, [which] contributes to political withdrawal, authoritarianism, and violence … society collapses into friends and enemies of the Singularity, the Risen Christ, or the Mahdi. …

Given the stakes—the future of humanity—enemies of the Ordo Novum must be swept aside. Apostates and the peddlers of mistaken versions of the salvific faith are even more dangerous than outright enemies, since they can fatally weaken and mislead the righteous in their battle against evil.

Obvious examples come to mind: Jonestown, the Unabomber, Aum Shinrikyo, the eco-fascism of the El Paso and Christchurch mass murderers. “Whenever contemporary millenarians identify particular scientists, politicians, firms, or agencies as playing a special role in their eschatologies,” he writes, “we can expect similar violence in the future.”

That this is correct will be obvious to you if you’ve been following debates on Twitter about the lab leak hypothesis. The hypothesis itself is not a conspiracy theory, but many of its adherents are conspiracy theorists par excellence, and their understanding of the way the world works is, at best, useless. Passionate emotions informed by the millennial instinct have swiftly eclipsed rational political suggestions for mitigating the risk of the next pandemic, whatever its origins.

As Hughes notes,

A more systematic and engaged analysis, on the other hand, would focus on regulatory approaches addressed at entire fields of technological endeavors rather than specific actors, and on the potential for any scientist, firm, or agency to contribute to both positive and negative outcomes.

Exactly. Let me see your detailed proposals for regulatory reform—not those extremely elaborate diagrams about the missing Fauci emails you’ve made for your special episode of My Podcast Will Save the World! Then I’ll believe you’re serious about mitigating the risk.

Eliezer Yudkowsky observes something similar in his essay, “Cognitive biases potentially affecting judgment of global risks.” The largest catastrophes in human history, he notes, involve deaths on the order of ten to the power of seven.

Substantially larger numbers, such as 500 million deaths, and especially qualitatively different scenarios such as the extinction of the entire human species, seem to trigger a different mode of thinking—enter into a “separate magisterium.” People who would never dream of hurting a child hear of an existential risk, and say, “Well, maybe the human species doesn’t deserve to survive.” …

The cliché phrase “end of the world” invokes the magisterium of myth and dream, of prophecy and apocalypse, of novels and movies. The challenge of existential risks to humanity is that, the catastrophes being so huge, people snap into a different mode of thinking. Human deaths are suddenly no longer bad, and detailed predictions suddenly no longer require any expertise, and whether the story is told with a happy ending or a sad ending is a matter of personal taste in stories.

Alas, this separate magisterium is but one source of important cognitive errors about catastrophic risk. There are many more.

But we must recognize them. Only then can we think clearly about these risks, devise a rational plan for mitigating them, persuade others it’s a good plan, then mitigate them.

That is the only rational thing to do.

The literature is vast; here are some suggestions: An upper bound for the background rate of human extinction, by Snyder-Beattie et al., who treat only natural risks—asteroids, stellar explosions, super volcanoes. They put the likelihood of human extinction within the next year to be somewhere between one in 15,000 and one in 87,000. The lower estimate puts us firmly in the range of “more probable than a car crash.” I’m not persuaded they’ve worked this out correctly, but give them a try and report back. The Global Catastrophic Risks Survey puts the odds of human extinction in the coming century at 19 percent. The Stern Review, which focuses exclusively on worst-case climate change scenarios, puts it at 10 percent. I believe most climate scientists would say this estimate is too high. Nuclear War as a Global Catastrophic Risk indicates there is no consensus. In The Precipice, Toby Ord puts the odds at one in six in this century, up from one in a hundred in the 20th. He focuses (correctly, in my view) on the risk from nuclear and biological weapons. I’m with him.

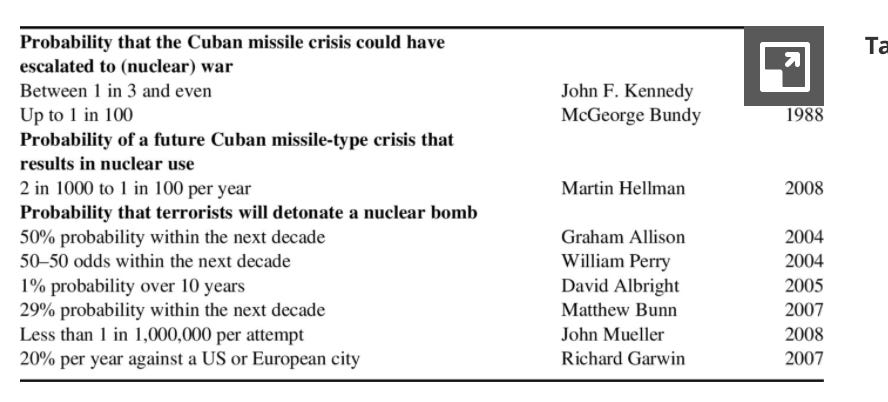

Here are some individual estimates of the likelihood of nuclear war or terrorism—which are not necessarily existential risks, but certainly catastrophic ones. It is notable that politicians who experienced a close call believe the odds to be vastly higher than people who haven’t had this experience.

Unless otherwise specified, in the volume that Milan M. Ćirković kindly sent to me.

![[Mardi 15 juin 2021 - webconférence] - Apocalypse cognitive [Mardi 15 juin 2021 - webconférence] - Apocalypse cognitive](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!syf0!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcf788363-882e-4156-b57d-77c3ac4af7cf_900x350.jpeg)

I believe that governments and citizens need to focus (within reason) on catastrophic risks. This requires greater scientific literacy of gov, media and citizens. A problem that pulls us away such a focus is that “read in an hour daily printed newspaper” of 20 years ago has been replaced by scattered and never-ending rabbit holes of information on all topics on the internet. National leaders need to display an example of necessary concern that populations can then aspire to.

The literature of apocalypse—extensive, lively, enduringly popular—suggests that humanity is not really blind to the possibilities of global catastrophe. On the contrary, we’re comfortable with them. They even give us a thrill. This quirk of human nature manifests itself in many ways, from the Human Extinction Movement to “The Walking Dead.” George Romero knew what he was doing when he invented the zombie apocalypse.

Why this is so seems fairly obvious: One person’s apocalypse is another person’s Declaration of Independence. TWD’s villains tended to be tyrants, warlords, gang chiefs, freed by the collapse of civilization to actualize their inner fascist. Sociopaths are all around us and no doubt a fair percentage of them would be delighted if things were to fall apart. So would other, even more sinister types.

I mention this because in thinking over what Claire has written here, it seems to me that the element of the death cult that lurks in the human subconscious has to be taken seriously. Getting people to think about the possibility of real-world catastrophe, apocalypse, extinction, may produce effects the opposite of those intended. Science, indeed, is the font of rationality. But on the whole people are irrational—as I was prompted to reflect today by the sight of a woman out for a walk in our spacious subdivision—wearing a mask. A small thing, you may say. But the Cult of Greta and that of Trump, etc. are not small things. It’s sobering to reflect that most people nowadays are no less superstitious than their ancestors, though their superstition may have a different focus.