We have a lot coming up for you this week, including an analysis of the significance of the election in Italy, an article about the protests in Iran, and more coverage of Russia and the war in Ukraine. But first, here’s the fourth and final installment of my thoughts about Peter Zeihan and political forecasting.

If you missed them, here are the first three installments—and an article I wrote about Zeihan a while ago.

Notes on Peter Zeihan, Part I: Is the old world order about to collapse?

Notes on Peter Zeihan, Part II Why Zeihan is gloomy

Notes on Peter Zeihan, Part III: On geopolitical forecasting

The Absent Superpower: Peter Zeihan and the Pax Americana

Today let’s consider the argument Zeihan makes in all four of his books, to wit, that the United States is poised to abandon the global economic order it has sustained for some four score years, leading to the complete collapse of global trade. These are his premises:

The United States established what he calls the Order—and what I would call the Pax Americana and globalization—for strategic, not economic reasons: It was a vehicle to defeat the Soviet Union.

The US offered prospective allies a bribe—a word he uses repeatedly. In exchange for joining an alliance led by the US, they received security guarantees and access to the US domestic market. The US Navy patrolled the seas, giving every nation the ability to trade anywhere in the world. It was a bribe because this Order was economically disadvantageous to Americans.

The Soviet Union having collapsed, the rationale for the Order has disappeared. The United States no longer wishes to be economically taxed by the Order, nor does it wish to expend blood and treasure to defend it.

Thus his conclusion:

∴ Because no other power is capable of replacing the United States, the Pax Americana and globalization are over.

Zeihan’s argument is valid—but it is not sound.

Let’s look at it carefully.

Zeihan explicates the argument above more fully in all of his books, using almost identical language.1 The points that follow are his, not mine.

The Accidental Superpower: The Next Generation of American Preeminence and the Coming Global Disorder, was published in 2014. It opens in New Hampshire, at Bretton Woods, in July of 1944. Before Bretton Woods, Zeihan writes, there was no global economic system as such:

Instead, various European nations maintained separate trade networks stemming from their earlier imperial ventures, in which their colonies served as resource providers and captive markets while mother countries produced finished goods.

Although they could have, he writes, being by far the most powerful nation left standing after the Second World War, the Americans didn’t recreate these circumstances. Instead, they opened their domestic market to everyone and used their navy to protect everyone’s maritime trade, no matter its purview:

Far from proposing a Pax that would fill their coffers to overflowing with trade duties, levies, and tariffs, the Americans were instituting the opposite: a global trading system in which they would provide full security for all maritime trade at their own cost, full access to the largest consumer market in human history, and at most a limited and hedged expectation that participants might open their markets to American goods. They were promising to do nothing less than indirectly subsidize the economy of every country represented at the conference.

Again—his argument, not mine; I don’t agree, as you’ll see below. Americans, he writes, never organized their own economy around Bretton Woods. And now, he writes, the system persists only because “Americans continue to pay the full price of sustaining it.”

Three years later, in 2017, he published The Absent Superpower: The Shale Revolution and a World Without America.2 As its title suggests, he argues here that the shale revolution will accelerate US detachment from the Order:

Shale didn’t start the American withdrawal—that began the day the Berlin Wall fell. Shale won’t end it either—the Americans won’t return until the day the US government decides the chaos and dysfunction of the Disorder unduly impinges upon its interests. But by removing energy dependency—the firmest and most self-interest-driven aspect of US involvement with the wider world—from the mix, shale most certainly accelerates and entrenches the global breakdown.

I don’t agree with this, either, for reasons I’ll note below. Again, he explains the origin of the Order in this book in terms of the premises above. He uses the word bribe here, too. “The best way to build an alliance,” he writes, “ was to flat out bribe one into existence.”

In all of his books, he stresses the massive economic benefits that accrued to the world from free trade:

The American-dominated free trade system ushered in the greatest era of peace and prosperity in human history. Global GDP expanded by a factor of ten. The global population tripled.

Along with the peace that devolved from American hegemony:

The massive, civilization-threatening wars of the past, (whether they be Franco-German, Russian-Turkish, Japanese-Chinese or imperial predation) all simply stopped, held in abeyance by the smothering security and wealth of the American network.

No argument from me on either of those points. They are correct—although arguably, the advent of nuclear weapons played a role in ending “massive, civilization-threatening wars.”3

But “suddenly, it was gone.” When the Berlin Wall fell, he writes, Americans lost interest in the wider world. The elder Bush, having supervised the peaceful disintegration of the Soviet Union, was ejected from office for his pains:

The next three presidents—Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama—were all domestic presidents uninterested in foreign policy unless the world rudely intruded upon their plans. None of them expressed an interest in replacing the Cold War strategic doctrine with anything new. Free trade was maintained as a hallmark of American policy, albeit now without the attached security prerogatives. There was no Bretton Woods II.

Yes and no.

Two years later, in 2020, Zeihan published Disunited Nations: The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World. He again describes the Order as “in essence based on bribes.” In this book, he argues that the end of the Cold War ushered in an era of American strategic incoherence:

When the Cold War ended, the nuclear boulder hanging over the American foreign policy and security and intelligence institutions dissolved—and took with it that unifying focus. During the Cold War, American global primacy was a requirement to fight the Soviets. Without the Soviets, simply maintaining American global primacy has become the de facto goal of US strategic policy. …

Without an overarching goal, America’s priorities change not year by year, but often hour by hour, with diplomatic, military, and intelligence efforts often working at cross-purposes.

He’s right about the strategic incoherence. I agree. The consequence of this incoherence, he writes, has been a foreign policy that somehow never achieves anything it’s supposed to and sours Americans on global engagement, tout court, causing them to pull the plug on the whole shebang:

Between America’s huge standoff distance and its relatively slim economic interest in the global system, the United States can wash its hands of everything outside of North America and go home. …

For most Americans, the conclusion that the United States should be less involved in managing the world is as reasonable as it is worrying. Such a view is now dominant on the Right and Left in American politics, across both the centrist and populist factions.

He’s right that this strain of thought is far more common than it once was. Dominant? Too soon to say: In this book, he prophesies NATO’s unravelling, the demise of international institutions like the United Nations, and an Asia dominated not by China, but by a remilitarized and nuclear-capable Japan. US troops will be withdrawn “within the next few years” not just from Afghanistan and Iraq, but from Turkey, Qatar, Germany, South Korea, Japan, and Italy. The United States will adopt a policy of unenlightened self-interest, becoming “positively imperial, almost Russian.” Indeed, it may actively destabilize the world:

Since 1946 American foreign policy has determined the shape of the world. When the Americans stop holding up the roof, they will note that the resulting power vacuum is bad, exceedingly bad, for most of the world. But they will also notice that in many cases the chaos works for America.

Disruptions in energy supplies would cripple American competitors, he writes, but because of the shale revolution, the US will not only be insulated from oil price shocks but capable of delivering them whenever it chooses. Degradations in maritime security won’t just destroy manufacturing supply chains, he writes, it will force them to relocate, and there’s only region where raw materials, production, and consumption are colocated, with no shipping required: North America. The more unstable the rest of the world becomes, the faster its capital will flee to the United States. It all adds up, he writes, to a United States that breaks bad:

Marry an American strategic, willing disregard for global security to a public that has become more comfortable with low-level, disavowable military activity to a military with global reach to a more mercantile approach to the world, and it is Anakin-falling-to-the-Dark-Side eeeeasy to envision a United States that seeks disruption rather than stability as both a tool and a desired end of foreign policy.

Finally, he makes this argument again in The End of the World Is Just the Beginning: Mapping the Collapse of Globalization, published just recently. But in this book, we’re no longer about to go home. We have gone home:

Thirty years on from the Cold War’s end, the American have gone home. No one else has the military capacity to support global security, and from that, global trade. The American-led Order is giving way to Disorder.

So there you have it: The Zeihan Theory of the American Era.

This leads me to my first question: If we’ve gone home, why are we still there?

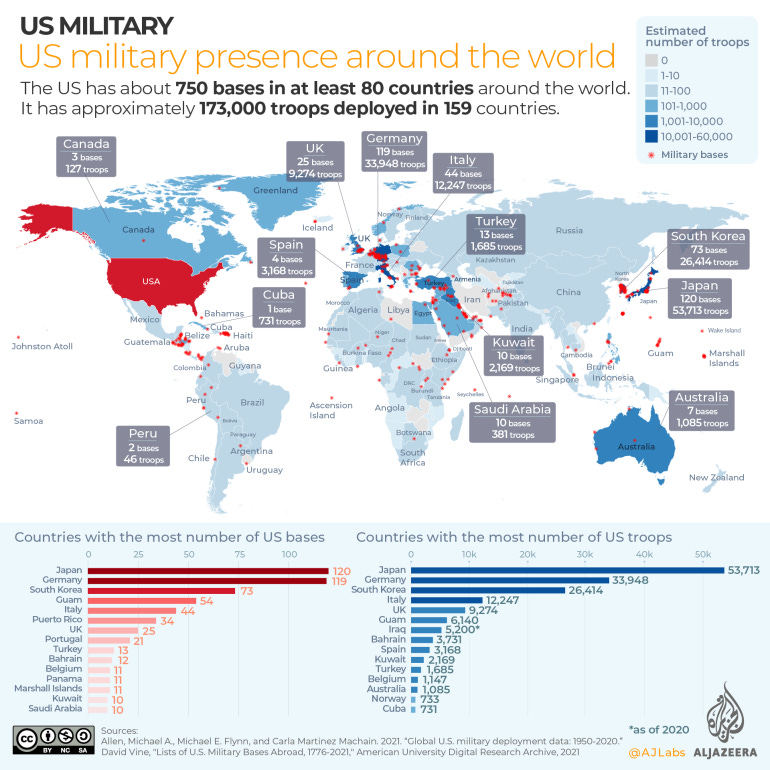

That charts is from 2000—I couldn’t find a good 2022 chart—but the numbers today aren’t significantly different. Since February, we’ve deployed more than 20,000 extra troops to Europe. We withdrew a handful of troops from Afghanistan—to catastrophic effect—but we’ve got more troops overseas, not fewer, than we did two years ago.

Why might this be? The obvious answer is that it isn’t true that following the Soviet Union’s collapse, “the nuclear boulder hanging over the American foreign policy and security and intelligence institutions dissolved.”4 You’d think that after the Cold War, we all lived happily ever after. But to the contrary, the United States now confronts an array of hostile nuclear powers, including—but no longer limited to—Russia.

Two unasked and unanswered questions haunt the Zeihan Theory: First, why did US fight the Cold War at all? And second—whatever answer he might give—why wouldn’t that logic apply to the world we’re in now?

The United States was never at risk of being invaded by the Soviet Union. The US enjoys—as Zeihan points—the world’s most protected geography, with nothing on its borders but Canada, Mexico, and fish. As he also points out, the United States isn’t dependent on global trade the way its allies are. Had the entire world succumbed to communism, the US would have survived.

Yes, as he observes, the Soviet Union had nuclear weapons. But so did we. We didn’t need a massive, globe-spanning alliance to protect ourselves from those. We needed a secure second-strike capability, and we had one.

The answer to the first question is that self-defense, in a narrow sense, was not our primary motivation for confronting the Soviet Union. Zeihan believes, as so many do in our cynical age, that US policy must be understood at two levels: There is the manifest content—how policymakers explain their behavior to the world—and the latent content, which is accessible only to those who have figured out how to decipher it. In such systems of thought, the latent content is always grubbier and more self-serving than the manifest content. In a Marxist version of this kind of analysis, US policymakers fill their speeches with handsome talk of freedom to conceal their real economic agenda, which is imperialist. According to vulgar pop-Marxists like Glenn Greenwald, Michael Tracey, and the national conservatives at Compact, it’s a truism that our foreign policy serves the interest of our ruling class, which profits from our military-industrial complex.

Like them, Zeihan doesn’t take our policymakers at their word. There is a disjunct, in his view, between the ideals we proclaimed at Bretton Woods and our real agenda. The word bribe sounds appropriately grubby.

I don’t think this kind of analysis makes much sense. I take our policymakers at their word, by and large. A massive body of evidence supports the claim that we fought the Cold War because the prospect of a world enslaved under the Soviet boot revolted us. We had sacrificed a generation’s worth of blood and treasure to secure freedom in Europe and Asia. We were damned if we’d see the world enslaved again.

Of course, human motivations are always complex. A massive government like that of the United States—placed in power by millions of individual voters, each with their own complex psychological agendas—can never be said to have a single reason for anything it does. US foreign policy, like that of any great power, emerges from a combination of discrete determinants: its policymakers’ appraisal of the foreign environment, historic memory, ideology, bureaucratic intriguing, the exigencies of elected office, the skill of the policymaking elite, and so forth. Policy emerges from a complex process involving all of these factors.

But in general—and especially given our system of government—we are not capable of sustaining any policy over a period of years without first producing a document, or several, that spells out what we’re trying to do and why. As a practical matter, no subordinate in our vast policymaking apparatus would know what to do or why without such documents, and so our behavior is rarely at significant odds with them. This leaves little room for concealed motivations.

There is no commonly accepted date for the beginning of the Cold War. The alliance between the United States and the Soviet Union began to crumble as soon as the war in Europe ended, in May 1945. Tensions were already apparent in July during the Potsdam Conference. A reasonable starting date, in my view, is 1947, when the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan were announced.

Traditionally, the United States was reluctant to be involved in European affairs. Most Americans felt there was a reason they and their ancestors had left that benighted continent. So why did Truman feel these policies were necessary?

In his speech to Congress in 1947, he elaborated several principles that have governed US foreign policy since. I don’t think this speech concealed any kind of hidden agenda. I think it is what he genuinely believed, and widespread support for this policy suggests it’s also what most Americans believed:

One of the primary objectives of the foreign policy of the United States is the creation of conditions in which we and other nations will be able to work out a way of life free from coercion …

We shall not realize our objectives, however, unless we are willing to help free peoples to maintain their free institutions and their national integrity against aggressive movements that seek to impose upon them totalitarian regimes. This is no more than a frank recognition that totalitarian regimes imposed on free peoples, by direct or indirect aggression, undermine the foundations of international peace and hence the security of the United States…

I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures. …

It would be an unspeakable tragedy if these countries, which have struggled so long against overwhelming odds, should lose that victory for which they sacrificed so much. Collapse of free institutions and loss of independence would be disastrous not only for them but for the world.. [My emphasis.]

Contra the Zeihan thesis, I think that US policymakers emerged from the Second World War with a set of ideas that determined their behavior. I tend to think ideas—and people—matter more to history than Zeihan does.

Throughout the 20th century, and even before, the US has vacillated between competing impulses in foreign policy, which we can loosely term isolationism and proselytizing. Both emerge from what Adam Garfinkle describes as US foreign policy’s Anglo-Protestant strategic culture:

[D]enials to the contrary notwithstanding, the United States [has] an ideology that issues from a distinctive strategic culture. That strategic culture is essentially a secularized manqué of Anglo-Protestantism, leavened with certain key Enlightenment principles that themselves derive partly from the Abrahamic moral tradition, and of course partly from Hellenistic thought as transmuted via Rome. The ideology derived from it asserts democratic government and market capitalism, linked to the point of necessary mutual reinforcement, to be valid best-practice principles everywhere, and principles with definitive positive implications for global security. Unaware of its particularist origins in religious culture, most Americans since at least the dawn of the 20th century have believed that this secularized ideology is universally applicable and self-evidently superior to all others.

Both isolationist and proselytizing impulses are related to the belief that the United States is blessed and exceptional. If Zeihan locates the sources of this belief in American geography—which is indeed blessed and exceptional, as Zeihan amply shows—I suspect its sources are closer to the place Adam locates them. But we can both be right about this.

Isolationism expresses the belief that America is a promised land that can only be fouled by contact with the rest of the world. We should therefore have nothing to do with it: It is a sh*thole of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell, and our interactions with it should be limited to “bombing the hell” out of anyone who vexes us. The perspective has a mirror image in a conception of the United States as divinely mandated to rescue the fallen world by turning every country on earth into peaceful, democratic traders like Americans.

Both are secular religious dogmas, and both operate powerfully on American foreign policy at different times.5 We are an ideological nation, even a zealous one.6

The United States emerged from the Second World War flush with confidence and strongly oriented toward one side of this continuum: The outbreak of the war demonstrated the defects of the isolationist posture; the outcome of the war showed the virtue of the proselytizing posture. Americans, broadly, had been convinced that a distinct set of mistakes had given rise to the war:

The Treaty of Versailles had pauperized and radicalized the defeated nations and led to the global depression of the 1930s. Whipsawed by unemployment, militarization—then aggression—became an attractive path to revisionist powers. The fascist infection took hold in bodies weakened by economic chaos.

The global economic system, or lack thereof, failed to alleviate the economic problems caused by the First World War—and particularly, failed to militate against rising protectionism, which aggravated the crisis.

Not least because the US failed to ratify the League of Nations and retreated into isolationism, collective security in failed in Manchuria and Abyssinia.

The Allies, weakened and demoralized by these events, failed to respond to Hitler’s remilitarization of the Rhineland.7

Historians have long debated the particulars of this account, but the point is that Roosevelt and Truman believed this, as did Americans generally. These are the mistakes they sought to correct in building the postwar order. And this is precisely what Americans believed they were doing at Bretton Woods.

Zeihan’s use of the phrase “Bretton Woods” to signify the whole postwar order is confusing. When he writes that China split from the Soviet Union to enjoy the benefits of Bretton Woods, he seems to have forgotten that by this point, Nixon had abandoned Bretton Woods. The reader knows what he means—he’s using it as a shorthand for “the Pax Americana and the global economy”—but it’s a bad shorthand, because “Bretton Woods” means something very specific, and it isn’t that. The point of the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, which became known as Bretton Woods, was to design a global monetary system, to be managed by an international body. Its provisions didn’t fully come into effect until 1961, and it collapsed in 1971. The two major accomplishments of the conference were the creation of the International Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development—the security alliances that underpinned the Pax Americana were still far in the future. The accord did not establish a system of free trade in which global maritime routes would be protected by the US Navy and the world given access to US markets. (If this was a bribe, it required all of the participants to be able to see the future.)

In any case, the Bretton Woods agreement wouldn’t have been a hidden vehicle to defeat the Soviet Union, because the Bretton Woods conference took place in July 1944, with the Potsdam conference still a year in the future. It’s plausible (if a stretch) to date the origins of the Cold War to Potsdam, but it isn’t plausible to date it to Bretton Woods. The US invited the Soviets to Bretton Woods. They sent a representative. We would have been prepared to include them: We were still speaking of Uncle Joe at this point. The Soviets only later refused to join the World Bank and the IMF. The precursor to Bretton Woods was the Atlantic Charter, which was drafted in 1941, well before the Cold War. And the Atlantic Charter’s roots were in Wilson’s doomed 14 points, which were in turn, as Adam Garfinkle points out, an aspect of our Anglo-Protestant strategic culture:

For example, consider Woodrow Wilson (a Presbyterian) at Versailles. One sees, in this case, the Calvinist backdrop brought to US foreign policy life, as Kurth put it, in Wilson’s “relentless opposition to the Habsburg Monarchy (the very embodiment of hierarchy and community, tradition and custom, and the only Roman Catholic great power) in the name of self-determination, which was an individualist . . . conception . . . ; and in his insistence upon the abstraction of collective security, as written down in the Covenant of the League of Nations.” All of this, with its dichotomous formulation of options and its deductive bias, seemed matter-of-factly normal and obvious to Wilson and to most Americans at the time, but did so only “to a people growing up in a culture shaped at its origins by Protestantism, rather than by some other religion.”

The Atlantic Charter involved most of the ideas that came to fruition as “the Order.”

First, [the United States and United Kingdom] seek no aggrandizement, territorial or other;

Second, they desire to see no territorial changes that do not accord with the freely expressed wishes of the peoples concerned;

Third, they respect the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and they wish to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them;

Fourth, they will endeavor, with due respect for their existing obligations, to further the enjoyment by all states, great or small, victor or vanquished, of access, on equal terms, to the trade and to the raw materials of the world which are needed for their economic prosperity;

Fifth, they desire to bring about the fullest collaboration between all nations in the economic field with the object of securing, for all, improved labor standards, economic advancement, and social security;

Sixth, after the final destruction of the Nazi tyranny, they hope to see established a peace which will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safety within their own boundaries, and which will afford assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want;

Seventh, such a peace should enable all men to traverse the high seas and oceans without hindrance;

Eighth, they believe that all of the nations of the world, for realistic as well as spiritual reasons, must come to the abandonment of the use of force. Since no future peace can be maintained if land, sea, or air armaments continue to be employed by nations which threaten, or may threaten, aggression outside of their frontiers, they believe, pending the establishment of a wider and permanent system of general security, that the disarmament of such nations is essential. They will likewise aid and encourage all other practicable measures which will lighten for peace-loving peoples the crushing burden of armaments.

The final clause, on disarmament, never came to pass. That these words were in the Atlantic Charter is one bit of evidence—among many—that the US didn’t anticipate the Cold War. The Atlantic Charter was signed on August 14, 1941—just a month after the Anglo-Soviet alliance was signed on July 12, 1941, that is, shortly after the beginning of Barbarossa. And there were two-and-a-half years of technical preparation prior to Bretton Woods. I would date the origin of the Cold War to Churchill’s Fulton speech. NATO was formed in 1949. We signed SEATO and a pact with the ROC in 1954, CENTO in 1955. The history of our Cold War alliances does not at all correlate to Bretton Woods, whether we use this term in the typical sense or as Zeihan uses it.

Bretton Woods emerged from the participants’ beliefs about the origins of the Second World War, to wit, that the Treaty of Versailles had left too many assets on bank balance sheets that were in reality unrecoverable loans, which led, they believed, to the 1931 banking crisis. The insistence by creditor nations on the repayment of Allied war debts, combined with isolationism, led to a breakdown of the international financial system and a global depression, made worse by protectionism and beggar-thy-neighbor policies that saw trading nations use currency devaluations and tariff walls in an attempt to raise exports and lower imports. Fascism, the participants believed, could not have gained purchase absent the economic crisis. Whether this story is correct is immaterial (of course, it’s incomplete). It’s what the participants believed. It’s unquestionably, for example, what Cordell Hull believed, as he wrote in his memoirs:

[U]nhampered trade dovetailed with peace; high tariffs, trade barriers, and unfair economic competition, with war … if we could get a freer flow of trade…freer in the sense of fewer discriminations and obstructions…so that one country would not be deadly jealous of another and the living standards of all countries might rise, thereby eliminating the economic dissatisfaction that breeds war, we might have a reasonable chance of lasting peace.

The US was determined not to repeat the mistakes that we believed had led to the worst war in history, and we understood it to be our responsibility to fix the global economic system: That we were as powerful as we were was a sign of our exceptionalism—or divine favor—and this came with commensurate obligations. US policymakers genuinely believed that unless they secured prosperity for the world, they would doom the next generation to repeat the experience they’d just endured.

But we certainly didn’t believe that we were ensuring the prosperity of the rest of the world at our own expense. Zeihan’s thesis rests upon a striking claim that he asserts repeatedly but never justifies. Free trade, he writes repeatedly, did not and does not serve the United States’ economic interests. As he puts it,

Since Bretton Woods was about swapping economic access for security control, the United States could not have used it to force-feed its products to its allies—instead it had to allow its allies to access US markets unilaterally. The United States had to be a net importer. It had to run a trade deficit. To do otherwise would have eliminated the incentive for countries as wildly divergent as Korea and China and Sweden and Germany and Argentina and Morocco to participate in the first place. For the Americans, free trade wasn’t about economics at all, it was a security gambit that was designed to solidify an alliance in order to fight a war. But that war ended three decades ago. America’s security needs have evolved, and soon so will its security policies—and that spells the end of globalized trade.

Korea wasn’t at the conference, and neither were Argentina, Morocco, or Sweden. Germany certainly wasn’t: We were at war with Germany. I understand that he’s using “Bretton Woods” as a shorthand, but for what? Is he defining Bretton Woods as “giving countries access to US markets?” Because the US certainly didn’t give “unilateral access” to its markets to every country in the world. I understand he’s using “unilateral access” as a shorthand for “low tariffs”—at least I think that’s what he means—but this is all bollixed up.

It is true that US domestic support for trade liberalization was enhanced by the emergence of the Cold War in the late 1940s. The public broadly accepted the government view that the United States should vigorously contest the Soviet threat not only by providing its allies with military aid and grants, but by lowering US tariffs. But this is a complete confounding of the arguments at the time about and for free trade. Democrats had since the late nineteenth century decried high tariffs as monopoly profits for the rich; low tariffs, they argued, meant low prices for goods consumed by the working man. (The parties didn’t switch positions on this until the late 1950s.) Zeihan seems to be forgetting here that trade benefits both sides: Low tariffs meant our allies could rebuild their economies by exporting to the US, yes, but they also meant Americans could buy cheaper goods.

And how did we “have to run a trade deficit?” In 1952, for example, we had an export surplus in every major industrial group (machinery, vehicles, chemicals, textiles, and miscellaneous manufactures) except metals. Save Great Britain’s position at the outset of the Industrial Revolution, the kind of economic dominance we enjoyed is unique in the history of industrialization: There were no protectionist pressures on the government—or no significant ones—precisely because of the abnormally favorable export opportunities. (We did protect our agricultural sector.)

I just don’t understand why he thinks we “had to run a trade deficit.” We were negotiating trade agreements under the terms of The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934, an innovation devised by Cordell Hull. The act gave the president authority to negotiate trade agreements that would reduced US tariffs in exchange for reciprocal concessions. Truman used this authority to negotiate the first multilateral trade round after World War II. The Geneva Round, signed in 1947, reduced tariffs bilaterally, not unilaterally, and these reductions were codified in the GATT—and the fundamental pillar of the GATT is the most-favored-nation clause, which requires all signatories to grant the same trade privileges to each other.

It is true that in the immediate postwar period, in some tariff negotiations, the US redistributed part of the economic surplus it reaped from its favorable export opportunities to other major industrial countries. It did so as a bribe, yes—to persuade those countries to enter the trade system. But in 1950, the developed countries’ tariff rates averaged 40 percent. Fifty years later, after the implementation of most of the Uruguay Round, they averaged 4 percent.

The growth in trade enormously benefited the US economy. His claim to the contrary seems to rest upon the disjunct between the cost of the American military and the size of the US trade deficit:

US defense spending throughout the Cold War regularly topped 5 percent of GDP—typically over twice the ratio of its allies. The American navy costs a cool US$150 billion annually (with another US$30 billion for the Marines). And most of all, the countries that have chosen to specialize in exports turned the American trade deficit into a $700 billion monster at the peak of the last economic boom.

Such costs were easily justified in the context of superpower competition, but as you may have noticed, the Cold War ended in 1989 and the Soviet Union collapsed just three years later.

If this is really his argument, it isn’t strong.

We really believed in free trade. (I still do.) We didn’t pull the phrase “free trade” out of a hat to disguise our desire for a set of allies. We didn’t believe that granting other nations access to its domestic markets would be disadvantageous to us economically—nor was it. In fact, in the early postwar period, the US believed that unless it helped Europe get its economy up and running again, it would not only plant the seeds of another conflict, it would lose its largest export market (that’s how it was sold to Republicans, anyway) and never be repaid for Lend-Lease. So no, this wasn’t a bribe. We wanted our money back.

Also, initially, US administrations believed the pressure on the balance of payments was transitional and largely related to the postwar global recovery. They were willing to wait it out. When it became obvious, in the late 1960s, that this was harming the US economically, we abandoned Bretton Woods on a dime. Maintaining it would have required elected officials to sacrifice domestic economic goals for international objectives, a trade-off they wouldn’t make, and didn’t.

My view here is orthodox. I believe the men who created the Order—from Cordell Hull to Harry White—said the things they said at the time because they believed them.

To be sure, we also had secondary reasons for fighting the Cold War. Among them was our belief that a world under Soviet domination would be a world without free trade, from which we benefited enormously—so much that freedom of the seas had been a key American foreign policy aim since France and Britain first threatened US shipping in the 1790s. If Zeihan is right and the United States accrued few economic benefits from free trade, this point has always entirely eluded American policymakers.

Zeihan is right that alone among the nations of the world, the United States could be a reasonably successful autarky, and this sense has no use for a Navy. But this doesn’t mean that we wished to be. We had gone to war four times before Bretton Woods to assert the principle of freedom of the seas—the quasi-war with France in 1798, the Barbary Wars, the War of 1812, and World War I. If maritime freedom wasn’t truly in our economic interest, this history is very hard to explain.

The US has run a trade deficit since it left Bretton Woods. But it also ran one through most of the 19th century. A trade deficit isn’t the same as an economic disadvantage. We run a trade deficit because we run a surplus in dollar exports, and we run a surplus in dollar exports because the dollar is the world’s reserve currency. If the US is tiring of free trade now, it isn’t because free trade was never good for the US. It’s because of an ideological fad.

But we can’t look at this merely in terms of the crude balance of trade. Subtracting our trade deficit from our military budget is a nutty way of assessing the value of the global order to the United States. None of this is a zero-sum game. The Pax Americana worked: Its benefits are wars not fought, lives not squandered—a great deal not just for the world, but for the United States.

I’m not sure, but I think Zeihan would reply—at least, I would, if I were trying to defend his position—that it doesn’t matter whether this account of the origin of the order is correct or whether the system still benefits the United States. The key point is that Americans no longer believe it does.

But is that so? There is evidence for this, yes. The best evidence is in the election of Obama, twice, and then Trump. Zeihan writes:

The commitment to that system has been steadily falling for some time. The efforts of three post–Cold War American presidents—Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama—highlight an ever-so-steady shift away from support for expanding the free trade network.

He points out that Bush failed to finish talks on deepening WTO commitments, and Obama “initiated no new free trade agreements with any countries.”

But the suggestion that Bush and Obama were trade-averse is unfair. Bush initiated the Trans-Pacific Partnership, and Obama invested eight years of effort in the negotiations. He lobbied for it vigorously. The TPP would have been the biggest trade deal in decades, covering 40 percent of the planet. Zeihan’s overall argument, however, stands: The TPP died because Democrats and the newly protectionist GOP rejected it. Point: Zeihan.

Strategically, though, Obama truly did represent a rupture. Obama was the first president since the end of the Second World War sincerely to believe that the world and the United States alike would be better off if the United States reduced its military posture and global presence. Obama negotiated the TPP, but largely ignored Russia’s aggression in Syria and Ukraine. He withdrew US forces from Iraq and pursued an arms control agreement with Iran despite its bloodthirsty expansion throughout the Middle East. And obviously, he was followed by Donald Trump, who ran for office on the isolationist slogan, “America First,” and then cheerfully pissed away as much of the Pax Americana as he was capable.

Surely this confirms Zeihan’s thesis, doesn’t it? The one-two punch of Obama and Trump does look like a trend. I even seemed to think so when I wrote this despairing article. But the trend lines aren’t unambiguous.

Zeihan expected the United States to shrug when Russia invaded Ukraine. He expected NATO to dissolve. But that’s not what happened. It could have happened, yes. It’s what might have happened had Trump been reelected. But it didn’t. On sober reflection, it isn’t clear to me that the Obama and Trump presidencies represented a long-term trend—one both inexorable and in evidence since the demise of the Soviet Union. Do these elections truly amount to a permanent change in the American disposition—a transformation so complete that it is a sure bet the Americans will, in the near future, abandon their commitment to global maritime security?

It’s hard to say why Americans elect the presidents they do, but instinct tells me both Obama and Trump were elevated to power by a mood of deep disgruntlement with American engagement overseas, as Zeihan believes. But the reason for this disgruntlement was owed less to our sense of strategic aimlessness in the absence of the Soviet Union as it was to our failure to achieve the outcomes we sought in Iraq and Afghanistan.

It’s possible that voters were expressing a temporarily isolationist mood. This has always been one of Americans’ foreign policy impulses, after all. But I don’t think it’s out of the question that American voters and policy makers saw the effect of leaving great, sucking power vacuums where the US military used to be and decided they’re not as eager to see this around the world as they thought. It’s hard to say. But what would our foreign policy look like if that were true? It might look quite a bit like our policy in Ukraine—particularly in light of our withdrawal from Afghanistan.

Zeihan believes we have already entered a world where the United States Navy no longer ensures the security of global shipping. Certain obvious facts, in this regard, deserve more attention than he gives them.

The first is that no one in our military, foreign policy, or intelligence bureaucracy is aware of this. The scenario does not even feature in any major planning or strategy document. It’s possible, I suppose, that it is the most closely guarded secret in the American national security community. It is also possible, as Zeihan suggests, that we’re about to suddenly reverse 80-odd years of policy overnight, in a fit of pique or on a whim.

But I think it less likely than the hypothesis that our national security documents roughly describe what we intend to do, and our behavior will roughly conform to those plans. I believe this not least because once bureaucracies of that size are committed to a plan, reversing them on a whim is about as practical as changing the orbit of the Earth. Some forces, once set in motion, are subject to severe inertia.

The Department of Defense, certainly, doesn’t think it’s about to cease ensuring global maritime security. In a recent report to Congress treating the matter, Annual Freedom of Navigation Report 2021, they describe the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention—which recognizes the right of all nations to engage in traditional uses of the sea—as an “essential part” of the “stable, rules-based international order,” which the United States is committed to defending.8

Some countries do not share this commitment. Unlawful and sweeping excessive maritime claims—or incoherent legal theories of maritime entitlement—pose a threat to the legal foundation of the rules-based international order. Consequently, the United States is committed to confronting this threat by challenging excessive maritime claims. …

As long as some countries continue to assert limits on maritime rights and freedoms that exceed coastal state authorities reflected under international law, the United States will continue to challenge such unlawful claims. The United States will uphold the rights, freedoms, and lawful uses of the sea for the benefit of all nations—and will stand with like-minded partners doing the same. [My emphasis.]

Our 2022 National Defense Strategy hasn’t yet been declassified, but Biden’s Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, issued in March 2021, begins this way:

Today, more than ever, America’s fate is inextricably linked to events beyond our shores.

There’s a lot of empty babble in this document, as you’d expect, but there’s not a hint of the words you’d expect if the United States was committed to a policy of abandoning its traditional role as maritime guardian. And remember: If no one puts the plan in writing—in some kind of overarching strategic document—then no one knows that this is the policy they’re supposed to carry out.

Despite Zeihan’s claim, we have not recalled the US Navy. We’re patrolling the SLOCs as if no one has received the secret memo. None of the US government bureaucracies foresees anything different, either. To judge from their policy documents, testimony before Congress, speeches, and behavior, the United States government believes it is entering a long, twilight struggle, not unlike the Cold War, against China. “China,” says the interim policy guidance, “has rapidly become more assertive.”

It is the only competitor potentially capable of combining its economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to mount a sustained challenge to a stable and open international system.

A “stable and open international system” is another way of saying, “the Order,” and this is another way of saying that the US plans to preserve that system. To this end, it says, we will “reaffirm, invest in, and modernize the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and our alliances with Australia, Japan, and the Republic of Korea.”

As we do, we will recognize that our vital national interests compel the deepest connection to the Indo-Pacific, Europe, and the Western Hemisphere. ... We will deepen our partnership with India and work alongside New Zealand, as well as Singapore, Vietnam, and other Association of Southeast Asian Nations member states, to advance shared objectives. …. we will reinforce our partnership with Pacific Island states. We will recommit ourselves to our transatlantic partnerships …

By restoring US credibility and reasserting forward-looking global leadership, we will ensure that America, not China, sets the international agenda, working alongside others to shape new global norms and agreements that advance our interests and reflect our values. By bolstering and defending our unparalleled network of allies and partners, and making smart defense investments, we will also deter Chinese aggression and counter threats to our collective security, prosperity, and democratic way of life.

And it says, explicitly:

We will ensure that our supply chains for critical national security technologies and medical supplies are secure. We will continue to defend access to the global commons, including freedom of navigation and overflight rights, under international law. We will position ourselves, diplomatically and militarily, to defend our allies.

Everything the Department of Defense publishes expresses the same program. Nothing suggests leaving allies to their own devices. We’re clearly preparing to counter a Chinese threat to freedom of navigation in the Pacific.

Nor has the State Department received the Zeihan memo. In January it released the 150th report in its Limits in the Seas series, a collection of legal and technical studies on various nations maritime claims.

Notable among these government publications is a Department of Energy report titled, America’s Strategy to Secure the Supply Chain for a Robust Clean Energy Transition. If you peruse it you’ll quickly realize that it may be theoretically possible for the United States to abandon maritime trade and flourish in the age of the shale revolution, but this is not what we plan to do. We plan to decarbonize our economy, making the US more dependent, not less, on global trade. This is why we have A Federal Strategy to Ensure Secure and Reliable Supplies of Critical Minerals, written by the Commerce Department, which likewise hasn’t received the memo:

The United States imports many critical mineral commodities from markets around the world. Specifically, of the 35 minerals designated as critical, the United States is import-reliant (imports are greater than 50 percent of annual consumption) for 31 of these minerals, and is 100 percent reliant on imports from other countries for 14 of these 31 minerals.

As the world economy grows, the United States will face increased competition for access to critical minerals sourced from foreign suppliers. Increasing trade with allies and partners can help reduce the likelihood of disruption to critical mineral supply chains. …

Establishing and maintaining close collaboration with US allies and other security partner countries to ensure national defense and economic security is also a priority for DOD.

From one document to the next, we assert that we’re not going anywhere. Take our Indo-Pacific strategy, for example:

The Second World War reminded the United States that our country could only be secure if Asia was, too. And so in the post-war era, the United States solidified our ties with the region, through ironclad treaty alliances with Australia, Japan, the Republic of Korea, the Philippines, and Thailand, laying the foundation of security that allowed regional democracies to flourish. Those ties expanded as the United States supported the region’s premier organizations, particularly the Association of Southeast Asian Nations; developed close trade and investment relationships; and committed to uphold international law and norms, from human rights to freedom of navigation.

The passage of time has underscored the strategic necessity of the United States’ consistent role. At the end of the Cold War, the United States considered but rejected the idea of withdrawing our military presence, understanding that the region held strategic value that would only grow in the 21st century.

No, we don’t sound like a country that plans to withdraw from the world—at all. A glance at today’s headlines suggests that the American public wants more naval power. Not a single article I could find today suggested US fatigue with maritime hegemony:

How Guam is transforming itself into America’s Pacific fortress.

US aircraft carrier, South Korean Navy conduct drills off peninsula.

US Navy looks for second Greece base at Alexandroupoli port of Greece.

Albania has offered NATO its Soviet-era Pasha Liman naval base.

I don’t discount the possibility that owing to a sudden shock, we may decide to do this. Nor do I dismiss the evidence of isolationist sentiments among American voters: Figures like Trump and Hawley are a measure of it. But this is most accurately described as ambivalence about our global role—not, “It’s over.”

Zeihan may be right that the majority of Americans no longer think the Order serves their interests. But if so, they’re wrong. The US can’t absent itself from a planet with instant global communications and ICBMs. If anything, we’re more dependent now on the wider world’s fate than we were at the close of the Second World War. In any world where it made sense for the US to fight the Cold War, it makes sense for the US to confront aggressive powers such as Russia and China and remain the global guarantor of maritime freedom.

It isn’t clear to me that the majority of Americans think otherwise. Isolationism is clearly a strain of American thought, but our expanding military budgets and the way we’ve responded to Russian aggression in Ukraine demonstrate that it’s not the only one.

Finally, let’s consider the claim that global trade would collapse overnight if the US Navy packed it in. I believe Zeihan is generally right about this, but not quite in the way he argues. A precipitous US withdrawal, from any region, would be an invitation to predation upon weak powers by antisocial larger ones. Armed conflict, as we’ve seen clearly in the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, does render critical maritime arteries impassible, both directly and by driving up insurance rates.

But short of this kind of armed conflict, would the impact of US withdrawal be quite as severe as he imagines? I’m not sure. Zeihan insists repeatedly that the US invented, from whole cloth, the entirely novel system of global free trade. But this is ahistoric. Between 1896 and 1913, world trade doubled, with little American assistance. Goods, capital, and people moved across borders freely—more freely than they do now, because passports weren’t required. This wave of globalization was driven by the construction of canals and railroads, and by technological advances such as better refrigeration, the steam engine, and the telegraph. (The recent wave of globalization owes as much to the advent of container ships and just-in-time manufacturing as it does to secure shipping lanes.) Global trade is possible without the United States watching over it.

It’s true that if China seized critical Pacific waterways and began denying access to them, global trade would suffer a massive hit. How likely is that, if the US retreats? I just don’t know. Short of that, however, I don’t see why the effect of American absence would be quite so extreme.

Zeihan’s concern about piracy seems exaggerated. Anti-piracy patrols are not beyond the abilities of many other nations. You don’t need the USS Gerald R. Ford to handle a few frisky Somali pirates. India and Nigeria, for example, are right now carrying out a joint anti-piracy operation in the Gulf of Guinea, which seems to be the world’s leading piracy hotspot.

I’m not really a piracy expert—though it would be cool if I were—but looking at Triton Scout’s most recent maritime threat advisory, it seems that yes, the United States prevented Iran from illegally seizing a US Navy vessel in the first half of September. But other navies carried out most of the world’s anti-piracy activity. No one is policing the Black Sea; and yes, this has had a dire effect on trade.9 But the EU is conducting operations in Gulf of Guinea, and it must be doing a good-enough job, because I haven’t heard of massive interruptions to trade there. ECOWAS, the report says, is strengthening its anti-piracy mechanism. Liberia, they say, is conducting an investigation into an incident involving Nigerian stowaways; the investigation appears to meet “national and international maritime standards.” Nigeria has jailed 23 people for piracy.

It seems to me that piracy—if not war—is a problem the world could handle without American assistance. The incentive is certainly there: In the first quarter of 2022, the value of global trade set a record of US$7.7 trillion—a point that by itself suggests globalization isn’t over. That’s a lot of money. The market for “maritime safety systems” is commensurately massive:

The global maritime safety system market is expected to grow from US$17.66 billion in 2021 to US$18.40 billion in 2022 at a compound annual growth rate of 4.19 percent. The marine safety system market is expected to grow to US$24.62 billion in 2026 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.56 percent.

The maritime safety system market consists of the sales of maritime safety system solutions and related services by entities (organizations, sole traders, and partnerships) that refers to planned solution and services implemented by shipping companies to ensure ship and marine environment safety. MSS aims to alert the system about the position and safety-related concerns about the ships in the vicinity, search and rescue coordination, and protection from terrorism, piracy, robbery, illegal trafficking activities, and others.

The main types of systems include ship security reporting system, automatic identification system, global maritime distress safety system, long range tracking and identification system, vessel monitoring and management system, other systems (automated manifest system), and automated mutual assistance vessel rescue system. Security reporting system refers to electric systems used to prevent or abate potential risks in ships by taking less hazardous processes programs to reduce injuries and property loss.

The largest market for these products is Asia. The OECD predicts that the global value of maritime industries will double, by 2030, from US$1.5 trillion in 2010 to $US3 trillion in 2030. Would maritime industrialists be incapable of coming to an arrangement, among themselves, to front a private navy?

This doesn’t solve the very real problem that wars make sea lanes impassable, as in the Black Sea, and I do believe wars would break out around the world if the US were precipitously to disappear, leaving a power vacuum. But they wouldn’t break out everywhere, simultaneously—I don’t think. Most trade would continue. Likewise, as Vivek has recently pointed out, a lot of cargo can be transported overland—growingly so, with China’s investments.

Finally, we’re growingly able to handle problems like piracy remotely. I’m not an expert, as I said, but how far are we from being able to patrol the oceans with a satellite and a few drone swarms? Could shipping be protected from space? If it could, it would obviate most Americans’ objections to military action overseas.

So, no, I’m not confident that he is right. Many of his predictions are subject to variation depending on small changes in his initial assumptions. He believes the United States will largely be spared the most pernicious consequences of climate change, for example. He may be right, but none of us know this for sure. His optimism about the United States’s future also seems unwarranted given the vastness of the global destabilization he predicts. If billions around the world now face starvation, as he says, and state after state will collapse, who wants to bet that none of the world’s nuclear weapons will go off? Even if we assume blithe American indifference to the event, it’s unclear what consequences this would have for American agriculture.

But I’m also not sure that he’s wrong. Complex systems, as Nicolas Taleb has observed, are fragile. The hyper-global specialization of supply chains combined with just-in-time logistics are complex. Any disruption causes the whole thing to seize up. Connective nodes become chokepoints: Think of that ship that got stuck in the Suez Canal.

In this sense, globalization is always vulnerable to collapse, at least temporarily. Maybe it will collapse because, as Zeihan envisions, the Americans go home, pirates have their way with the world’s container ships, and insurance rates skyrocket. Maybe it will collapse because all the longshoremen are out sick owing to a global pandemic, which is exactly what happened at the ports in Long Beach and San Pedro, through which 40 percent of American trade passes. Anchored ships piled up, waiting to be unloaded, while trucks hauling containers for export sat in twenty-mile-long traffic jams. Americans were bitterly thwarted in their quest to buy iPads, diapers, chicken wings, and new cars.

Something that screws up the global supply chains is a likely, predictable event. How often will it happen? More and more, given the growing complexity of these chains. In this sense, Zeihan’s prediction is overdetermined: Globalization will be repeatedly interrupted, because it is by nature fragile.

Clearly, any country capable of doing it would be well-advised to reshore the production of critical items such as medicine and microchips. This would not only make them more robust in the face of shocks, it would allow them to support countries that aren’t capable of reshoring.

Zeihan is most worried about countries that haven’t achieved a level of industrial sophistication sufficient to produce what they need closer to home. He’s right to be. The Democratic Republic of Congo isn’t going to reshore its chip fabs because it never shored them in the first place. The more redundancy we build into the system now, the less apt these countries are to sink back into the Middle Ages when the next massive shock takes place. This is already happening, and in this sense, Zeihan’s prediction is correct.

But does this mean globalization will come to a screeching halt, permanently? Will all the supply chains be repatriated? Will the billions starve as a consequence? That’s a different question.

And my answer is: probably not.

This brings my remarks on Peter Zeihan to a close—mercifully, because there are so many other things I have to do. But stay tuned: Tomorrow, I have a Peter Zeihan surprise for you.

Geoff, I hope you feel I’ve answered your question.

This argument stays the same; curiously, many of the predictions change.

In this book, Zeihan predicts a Russian-European war and a war between Saudi Arabia and Iran. The US, he predicts, will regard both with aloof detachment even as Syria, Iraq, Jordan, Yemen, and Lebanon “lose the ability to maintain populations more than one-third their current size” and 60 million people become refugees or perish of famine and thirst. The disruption and destruction of Persian Gulf oil production and export capacity will trigger a global depression lasting years. The United States will flourish, with its corporations “move from place to place, cutting deals and making money with a flexibility and ease that is sure to generate intense dislike,” becoming infamous for “Reach without interests. Capacity without commitment. Corporate without government. For though America may be withdrawing from the world, that is a far from saying that Americans will be nowhere to be found.”

Many will point out—correctly—that the Cold War was far from bloodless and American hegemony often brutal. What of Vietnam, Indonesia, Iraq? All points conceded. But these were not conflicts on the scale of the First and Second World Wars. This is no consolation to their victims, to be sure.

There is no reason whatever to think the risk [of a nuclear exchange] eradicated [since the end of the Cold War], nor even diminished. It is true that the United States and Russia now have significantly fewer nuclear weapons. But this misses the point. We had enough to destroy ourselves many times over. We still have more than enough. There are an estimated 13,900 nuclear weapons in the world. Russia and the United States possess 93 percent of them. This is enough—more than enough.

Some believe the risk of deliberate nuclear war has been reduced with the end of the Cold War. They have no good reason to believe this. Putin’s regime is as hostile to the United States as the Soviet Union was. North Korea is certainly as hostile to the United States as the Soviet Union was. It has tested ICBMs designed to strike the entire continental United States. It has a large inventory of theater ballistic missiles.

Only recently, the head of US Strategic Command testified before Congress that China is putting its nuclear forces on higher alert, and neither the United States nor its allies understands quite why … What’s more, we know that terrorists have attempted to procure nuclear weapons. This is a staggering constellation of nuclear risk.

But Claire, I hear you saying. You’ve just rejected the idea of explaining our foreign policy by appeal to its latent content. Yes, I have. But here the idea of latent content is more useful. I could defend this point at greater length, but at some point, I have to press “send.” If you’re disturbed by this inconsistency, ask me and I’ll discuss it in the comments.

We must be, because we’re a credal nation, and without a shared creed, we don’t hold together very well—as everyone can see.

Zeihan is right to say that younger Americans no longer know this in the instinctive way that all Americans once did. The Second World War is retreating from memory. Trump was able to run on the isolationist slogan “America First” without causing the universal revulsion this would have a generation before. (It did cause widespread revulsion.)

The phrase “rules-based international order” is US government-speak for what Zeihan calls the Order.

There is good news here, though: Black Sea trade pact stabilizing food prices, UN says.

My initial thought is that there’s enough right to go all around. The guy seems right on some things, wrong on others, and speculating the rest of the time. I was 11 years old when I first saw Europe in 1959. Much of London hadn’t been rebuilt and some areas looked like long-term construction zones. Paris, not so much. I didn’t see enough German cities, which means they were off the tour for whatever reason—still bombed out a bit?—but I recall Cologne and the scaffolding wrapping the the cathedral to repair the damage inflicted by Allied bombs. A street in Genoa was being finished and I remember photos of Il Duce hanging from a light post or something. That was the tourist zone. People talked at length of their worry that Italy was about to go Communist.

All of which to say is that I still don’t have a sense of how much of Europe was destroyed. My guess is that Germany and Poland were even dystopic in places, but as we now see Ukraine getting hammered, I have to appreciate that Europe was as bad, if not worse. That being the case, the U.S. could not hold back and do nothing and just hope it would all get built back better somehow. Point being, I guess, that certainly there were mercantile reasons for the Marshall Plan and subsequent trade deals, but there was also a fear of Soviet hegemony, which probably had both idealistic and mercantilistic concerns.

We had a housekeeper for a couple of years in the late 1950s, Lisa Ginschel, who was a DP from Germany. Her son was about my age and spoke almost no English. She was mortified of Russians, though. My wife and I had a dear friend from Baden-Baden in the early 1980s, and she likewise was mortified of Russians, saying that most Germans were as well.

Full circle, is Zeihan right? If he misses what I witnessed as late as 1959-Europe, and it seems to me he did based on your contrapuntals, then no. But some of his points are worth pondering fairly seriously.

Claire, you wrote, "Is Peter Zeihan right?" (about the imminent collapse of globalization and thus the end of civilization as we have known it) and then gave us a summary of his major arguments. , You agree with some and disagree with others, but in the end you conclude (if I understand you correctly) that although he is wrong on many of his assumptions, he could be right-ish because, after all, globalization is a complex system of inter-dependent sub-systems, and the collapse of one critical "node" can disrupt the smooth operation of the whole.

I have a less well-informed, unsophisticated way of answering the question you pose, based only on watching Peter Zeihan's video (haven't read the books; don't plan to). He is NOT right, because the theorhetical underpinnings of his theory are weak -- they only explain some things, they are not a theory of everything.

While his ideas are entertaining and thought-provoking, he suffers from the usual shortcomings of know-it-all didacticism: like many Brilliant People, he's so blinded by his brilliant insights he overlooks the boring little mundane factors that make a huge difference in how things ACTUALLY turn out (as opposed to the way the Brilliant Person's thought experiments say it OUGHT to turn out). If evidence is needed to buttress this assertion, I would cite how the poor morale and training affected performance of the Russian troops invading Ukraine upended the "conventional wisdom" that the UKR forces were doomed and the RUS would roll over them in a matter of days. Okay, I admit that I was one who fell for the CW, but then I recognize that am not a guy with brilliant insights. Of course, as a fellow with books to sell, Zeihan needs to have the courage of his convictions, so on the whole I think it is very helpful to our understanding of how things work that we consider his theories carefully, as you have, Claire (thank you).

I have another quibble with him: much as I agree that the US has been the essential superpower in post-WWII global affairs -- the present-day world would be a very different place, absent US leadership -- I think Zeihan affords American policy too much agency in affecting world affairs, and far too often our policy is made by ill-informed people in power, people all too likely to be careerists telling superiors what they think they want to hear, or political appointees in thrall to a particular political ideology. (the Dulles bros come to mind, or the innumerable Republican political zealots who infested the American administration of post-invasion Iraq).

Personally I find it thought-provoking and entertaining to listen to a very knowledgeable guy like Zeihan, who comes up with an fresh and appealing theory that seems to explain why things have happened the way they did (or the way the Brilliant Person portrays them), and then to uses theory as a kind of Automatic Turk prediction machine to foresee what will happen in future as a result. But human behavior is not so predictable as are physical laws of nature, and BP's do love to expound on their theories. And I certainly welcome hearing them.