From Claire—If you’re only tuning in now, you’ve a bit of catching up to do. For the past week and more, the Cosmopolitan Globalists have examining this question: Omnibus perpensis, what’s the best way to provide energy for the globe’s 7.9 billion people?

The debate has been lively, and despite the bitter acrimony, enlightening. Certainly, I know much more about energy than I did when we started. I’ve considered the question in much greater fullness and come better to appreciate its fiendish complexity. I hope our readers feel the same way. I hope, too, that you share my gratitude to our moderator, Ron Steenblik. His even temper and mastery of the politics and literature of energy policy made this exercise particularly fruitful.

Here’s a Table of Contents for those who’ve recently joined us:

Preface: We propose a wild, week-long debate.

We can’t electrify everything. Renewable enthusiasts, take note.

Anthropogenic Global Warming: Our climate scientist presents the evidence.

More questions for Dr. X—and answers.

Then, don’t miss our two-part Battle of the Energy Superfighters on the Cosmopolicast:

Finally, on the Main Page, look for the image below. These are dedicated forums for debate. The Grand Prize for debating will be very grand indeed.

I genuinely think—and yes, I would say this, but it’s true—that this is a more balanced and useful introduction to a massively complex issue of global policy than you’ll find elsewhere on the Internet. If you can find a better one, tell me. We’ll hack their site and sabotage their server. Sure, if you study the academic literature, you’ll find much of the ground we covered explored in greater detail. But I know no other newspaper, magazine, or newsletter meant for the wider public that has offered readers something like this. And quite unlike the academic literature, the Cosmopolitan Globalist is well-written.

If you agree this has been a worthwhile exercise, would you please subscribe?

If you’re a pleased subscriber and want us to keep it up, would you consider becoming a Founding Member? You’d subsidize our free readers, who would, I hope, be grateful. The world would be slightly better-informed, more thoughtful, and more deliberative as a result.

You could also give someone you know a gift subscription. Perhaps you’ve heard someone complain about the media recently? Give him a subscription and tell him, or her, to come over here and help us build something we all like better.

If you’d like to keep reading without paying, would you please share the newsletter and encourage your friends to pay?

This week has made me optimistic about the future of the Cosmopolitan Globalist. This morning, I looked on everything we made this week, and I saw that it was good. Yes, it’s genuinely a good product. Excellent value for the money, too. I suspect the market for what we’re doing exists. But we need to become better-known, so that people who want to read things like this know where to find us.

Scientific uncertainty and energy policy

By Dr. X

How should we think about scientific imprecision in climate forecasting? Say a man’s skydiving for the first time. He’s at 10,000 feet, ready to jump out, putting on his radio headset. The instructor says, “Listen carefully. I’ll tell you when you need to open your parachute.” The guy jumps out—and whoa, it’s spectacular out there! He’s enthralled. When he reaches 5,000 feet, he hears the instructor: “Time to open your parachute!”

The skydiver replies, “No, not yet! This is great! I’ve got plenty of time.”

A few seconds later, the instructor says, more urgently: “You’re at 3,000 feet. You need to open your parachute.”

“A little longer!”

“You’re at 1,000 feet! Open your parachute!”

“Not yet!”

“Damn it! You’re at 500 feet! Open your parachute!” Not yet. “You’re about to hit the ground! Open your f*cking parachute!”

“That’s OK! I can jump from here.”

In 1990, climate scientists said, “There are reasons to believe humans may be changing the climate. To be safe, we should begin the transition to a low-carbon economy.”

Politicians said, “That’s nice. There’s not enough evidence. Let’s study it some more.”

“It’s the year 2000,” we said. “Now we’re confident humans are changing the climate. We should cut fossil fuels while there’s still time to do so gradually.”

“That would be economically ruinous. Let’s wait.”

“It’s 2010. Climate change is increasingly urgent, and if we don’t act now, there will be grave damage to humans and the natural world.”

“What are you, some kind of socialist? Let’s wait.”

“It’s 2020! Cut the f*cking greenhouse gases!”

“Come now, you’re being alarmist.”

With that in mind, let’s consider this question from contributor WigWag:

John Kerry, President Biden’s climate Czar, recently said, “Well, the scientists told us three years ago we had 12 years to avert the worst consequences of the climate crisis. We are now three years gone, so we have nine years left ... ”

My question, Dr. X, is whether you think the data generated by climate scientists is so overwhelming and so amenable to precise analysis that scientists can determine the exact year when, absent dramatic reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, “the worst consequences” (whatever that means) will result?

To put it another way, is there now or has there ever been, a consensus of climate scientists that we are currently in a short window of now nine years where if we don’t take severe action calamity becomes inevitable?

Kerry made this claim in a CBS interview on February 19. Climate scientists cringe when politicians say things like this. I don’t know any scientist who would say we have exactly nine years left to save the planet. WigWag is right to question Mr. Kerry’s precision.

Lack of precision in climate science is not, however, a good reason to delay reducing greenhouse gas emissions—no more than lack of precision in assessing a skydiver’s terminal velocity would be cause to delay opening the parachute.1

Here’s where the “nine years left” claim probably comes from. Article 2(a) of the Paris Agreement, adopted in 2015, specifies a goal:2

Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;

Since that year, we’ve been trying to determine what constitutes dangerous human interference. But we can’t specify this precisely, because it depends on uncertain climate projections and your definition of “dangerous.”

The global average temperature has risen, again, by about 1.2 degrees C since 1850, and most of this warming is the result of human emissions of greenhouse gasses. CO2 levels have risen from 280 ppm to about 420 ppm; the concentration of methane, the second most important GHG, has increased from about 700 ppb (parts per billion) to 1900 ppb. Since we can see harmful impacts of climate change today—ice loss, rising sea levels, an increase in droughts and floods, among other things—some would say we’ve already passed the threshold for dangerous human interference. Others would argue people can adapt to this, so it isn’t yet dangerous. Still others would say, “Dangerous compared to what?” After all, it is dangerous, too, suddenly to stop farming your crops, heating your homes, and running your hospitals.

One way (though not the only way) to draw the line is to say it’s dangerous to pass certain tipping points. A climate tipping point is said to occur when a system transitions to a new state, one from which it can’t quickly recover—even if the extra greenhouse gasses could magically be removed.3 Systems with abrupt transitions are said to display nonlinear behavior, or hysteresis.

It’s a common misconception that the climate system has a tipping point such that if we stay on the near side of that point, we’ll be fine, but past that, we’re doomed. In fact, many parts of the Earth system are approximately linear, as are many impacts. Raise the temperature 1 degree, and things get bad; 2 degrees, and they get worse; 3 degrees, and they are profoundly worse. But there’s no climatological red line.

So when people ask me if it’s already too late, I always say no. Any steps we take today to cut greenhouse gases will give us a nicer climate in the future than we’ll have if we don’t.

Some natural systems, however, are strongly nonlinear, such as the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. If temperatures in the Antarctic rise by 1 degree C, we might see only modest ice loss. But if temperatures rise by 2 degrees, parts of the ice sheet might destabilize, raising the global average sea level by 3 meters or more in the next few centuries. Once this process starts, it is probably irreversible, so we don’t want to cross this threshold. Unfortunately, we can’t yet say where precisely the threshold is, just “about 2 degrees, give or take a degree.”

With these complexities in mind, the Paris Agreement negotiators tried to set targets that are politically and technologically feasible yet wouldn’t leave the world on a dire trajectory. Small island nations played a decisive role in adding the 1.5 degree goal to the final agreement.

In 2018, the IPCC published its Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 degrees C, laying out what we can say with various levels of confidence about the difference between 1.5 degrees of global average warming and larger amounts. As a result, 1.5 became an iconic number. Would 1.5 degrees of warming be much worse than 1.4 or much better than 1.6? Probably not, but people like to set goals using round numbers. Roger Bannister would not have become famous for running a mile in 4:03.

Many think the 1.5 degree target is unachievable, but I prefer it to the more vague target of “well below 2 degrees.” I’m risk-averse. I know, from personal experience, that catastrophic things do happen, so I’d rather build in margin for error than count on being lucky. Recent advances in renewable energy have given me hope that 1.5 degrees might be technologically feasible.

Reasonable people may differ about the right target—1.5 degrees versus 1.7 degrees, say—because climate science and economics are imprecise. My sense of the evidence, however, is that warming above 2 degrees would be very dangerous. Some economists argue that the cost of staying below 2 degrees exceeds the benefits, but their models strike me as undervaluing things that are hard to value and too severely discounting the future. I agree with Noah Smith that climate economics has failed usefully to inform policy discourse.

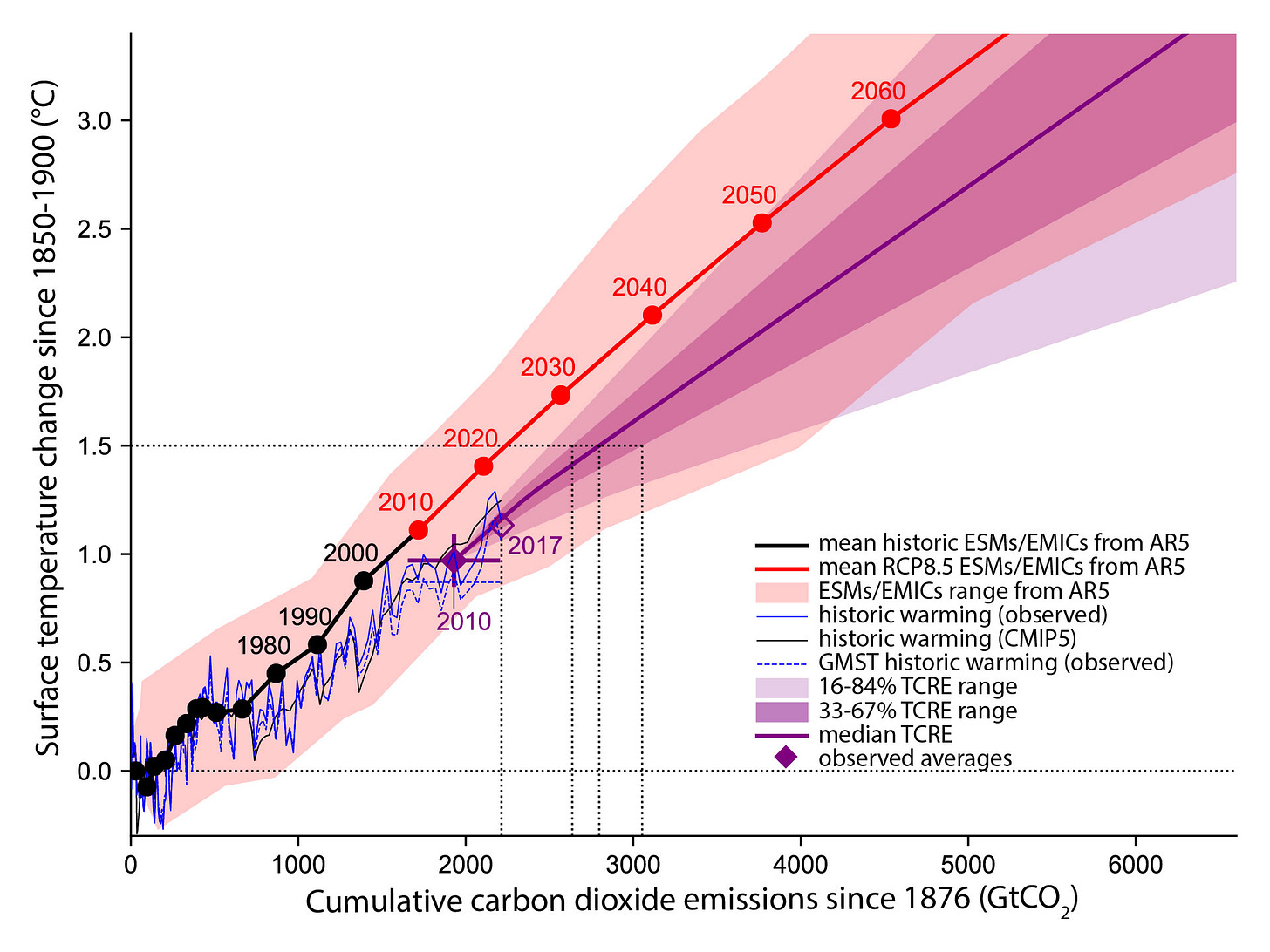

If our goal is 1.5 degrees, how fast do we need to cut CO2 and other greenhouse gasses to avoid exceeding the target? What, in other words, is the remaining carbon budget? Computing this budget is one way to answer the question, “How many years do we have left?”

Humans now emit about 40 Gt (40 billion metric tons) of CO2 each year, a bit less during 2020 because of the pandemic. Emissions haven’t yet peaked. Since the late 1800s, we’ve emitted about 2200 Gt, bringing us 80 percent of the way to 1.5 degrees warming. Assuming a linear relationship between CO2 and warming, a back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that if we emit another 500 or 600 Gt of CO2 , we’ll get to 1.5 degrees. At the current rate, that’s between 12 and 15 years.

The IPCC authors don’t rely on such a simple calculation; they assess many climate observations and models. But they get a similar answer: if we’re to have a 50 percent chance of meeting the 1.5 degree target, our total CO2 emissions, starting from 2018, must not exceed 580 Gt.

With 420 Gt, the odds rise to 67 percent; with 840 Gt, they drop to 33 percent. The report is clear about how they arrived at these numbers.

The remaining carbon budget is sensitive to the temperature target. If the target is raised to 2.0 degrees, the carbon budget increases to 1170 Gt, 1500 Gt, and 2030 Gt, respectively, for 67 percent, 50 percent, and 33 percent odds of success. Compared to 1.5 degrees, the horizon for emissions cuts more than doubles—from under 15 years to three or four decades.

The IPCC assigns medium confidence to these estimates. Sources of uncertainty include the historical temperature record and the climate response to future emissions of GHGs other than CO2. Long-term feedbacks of greenhouse gas emissions, such as the release of carbon and methane from thawing permafrost, may cause more warming. So the 12-year figure cited by Kerry and others is linked to a 1.5 degree temperature target, and to IPCC statements like this one:

Without increased and urgent mitigation ambition in the coming years, leading to a sharp decline in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, global warming will surpass 1.5 degrees C in the following decades, leading to irreversible loss of the most fragile ecosystems, and crisis after crisis for the most vulnerable people and societies.

The IPCC often uses round-number years like 2030, 2050, and 2100 in its projections. The statement above, made in 2018, suggests a window of about 12 years for deep cuts in emissions. Obviously, though, scientists don’t believe there’s some bad climate juju in years that end in zero.

Kerry’s statement is confusing and doesn’t reflect the science. Maybe he means well and is trying to convey a sense of urgency, but I think it’s a mistake to make misleading arguments, even for worthy goals. Suffice to say my kids are not allowed to beg off homework because some say the world will end in fire.

Does this mean we can safely delay cutting greenhouse emissions? It does not. The true budget is as likely to be below the IPCC’s best estimate as above it. And any GHG cuts made today will reduce harmful climate change in the long run.

Given a risk-averse 1.5 degree goal, my carbon budget preference would be about 400 Gt—roughly ten years of emissions at the current rate. I’d aim to halve emissions in the next decade, at least in countries with high emissions like the US. In the following decade, I’d try to get as near zero as possible, anticipating that some sectors will be hard to decarbonize and take longer. I’d also aggressively cut emissions of other GHGs. This recent study suggests relatively low-cost methane reductions could spare us a quarter of a degree of warming by mid-century, buying us more time to cut CO2. So my timeframe would be similar to Kerry’s, but I’d be less numerically precise. And I’d justify it differently.

Here’s the first exchange between Dr. X and Eric Dyke.

I’m greatly touched by Mr. Dyke’s kind words. Let me try to answer two more of his questions:

Critics say that research funds are only being directed to those who support global warming, and those who do not are rejected. Do you see that happening?

This is hard to answer with a simple yes or no. Let’s define “support for global warming” as accepting the claim I’ve made here previously: The Earth’s climate is warming, and most of the warming is caused by humans.

This claim is uncontroversial among climate scientists, and it’s true that nearly all government funding goes to researchers who support it. To say in 2021 that the Earth isn’t warming, or that it’s warming for exotic reasons for which there’s no evidence, is at this point so far away from the scientific conversation that it’s like claiming the Earth is 6,000 years old. Sure, many people believe in a young Earth, but that’s not due to arguments from geology, biology, or astrophysics.

Nonetheless, there’s room to wiggle with a word like “most.” Are greenhouse gasses responsible for virtually all the warming since 1950, or only, say, two-thirds? Although natural variability can’t by itself explain the observed warming, it could account for part of it. If so, then the climate’s sensitivity to greenhouse gasses would be at the low end of the predicted range.

We use models and evidence from past climates to estimate the global, long-term average warming from doubling atmospheric CO2. This figure is known as the Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity. According to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report,

Estimates of the Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity (ECS) based on multiple and partly independent lines of evidence from observed climate change indicate that there is high confidence that ECS is extremely unlikely to be less than 1 degree C and medium confidence that the ECS is likely to be between 1.5 degrees C and 4.5 degrees C and very unlikely greater than 6 degrees C.

That’s a large range, and we’re still trying to narrow it. (Note the difference between ECS and transient climate sensitivity; the latter indicates changes in temperature at the time of CO2 doubling. The difference is owed to warming that takes place decades after greenhouse gasses are introduced to the atmosphere.)

Suppose that after analyzing a new source of paleoclimate data—ancient lake sediments, for instance—I have reason to suspect ECS is only 2 degrees, or perhaps even lower. Yet I need more observations to strengthen my case. I think I could write a compelling grant proposal; my chances of getting research funding would be just as good as they’d be if my new data pointed the other direction.

Now let’s say I get funding and gather more observations, but find that alas, the new data suggest an ECS of 3 degrees—in the middle of the consensus range. My professional and ethical responsibility would be to publish what I’ve learned. Conversely, if I expect to find medium or high ECS, but instead find that it seems to be lower, I need to publish that. If I have an ideological commitment to a high or a low ECS such that I refuse to publish results in conflict with that commitment, funding bodies will notice that I’ve taken their money and published nothing. So will quite a few people. I’ll be less likely to get funding in the future.

This doesn’t mean there’s no such thing as scientific fraud, fudged results, or observer bias; of course all these phenomena exist in science, as they do in any human endeavor. But scientists are in competition for the same jobs and grant money, so we do check each other’s work carefully. It’s very hard—as it should be—to get peer reviewers to sign off on a weak argument. Remember: my fudged results are my rival’s straight shot to tenure and the corner office.

The harmful effects of global warming are stated everywhere in great detail. Are there no countervailing benefits?

Good question. On average, people are better adapted to the steady climate of the past 1,000 years than to the warmer climate we’re creating. But temperature and rainfall patterns could shift, for example, making the US Great Plains less conducive to growing wheat and Manitoba more. That’s not to say that climate change will be good for everyone in Canada, but it would be going too far to say there will be no benefits.

I’d caution, though, that it’s too simplistic to imagine a warmer climate will translate to more bountiful harvests. You can’t make infertile soil fertile by warming it. A higher evaporation rate could dry out the soil, too. Too much CO2 might make crops less nutritious. There may be no net gain. Nature is full of surprises. (Although there are not so many that we’re unable to model the fundamentals.)

I thank Mr. Dyke for following up on Bill Gates and the polar bears. If Bill Gates questions whether solar energy can meet the power demands of Tokyo, I’m inclined to agree. Japan has ten times the population density of the US and much less land available. Solar energy will work well for the American West, but not for everyone. I also agree about innovating in many directions. Who wouldn’t?

It’s interesting that neither of us found peer-reviewed evidence for significant changes in the total number of polar bears. Maybe they’re not declining. Maybe they are, but there’s no clear relationship between the decline of sea ice and the decline of polar bears. Maybe it’s hard to measure.4 Whatever the case, I’m sure we all wish the polar bears well.

I became a scientist, in part, because I wanted to help expand the store of human knowledge in a useful way. In a broad sense, scientists have done our job. We’ve shown that human-emitted GHGs are changing the climate. Since a 1.5 degree mitigation pathway is much more challenging than a 2 degree pathway, there’s still scientific work to do; we have yet to figure out which pathway is optimal. But broadly, we’ve delivered the goods. We’re confident that humans are changing the climate.

Now it’s up to citizens and their governments to act on this knowledge. Whether to do so, and how fast, are moral and political questions, not scientific ones. How do we weigh the well-being of future generations against our own? How could we make this transition less painful? Above all: How much risk do we want to take?

I know what you’re thinking. “Dr. X., do we have nine years to save the planet or not?” Well to tell you the truth, in all this excitement, I’ve kind of lost track myself. But suppose there is no mitigation at all, GHG emissions track the IPCC’s ssp5-8.5 high-emission scenario, and by 2100, CO2 reaches 1100 ppm, which is close to quadrupling. Assume ECS of 3 degrees C, a median estimate. By 2100 or soon after, we would have 6 degrees C of global mean warming—about 11 degrees F. With massive release of CO2 and methane from thawing permafrost, it may be too late to mitigate. Global sea level could easily rise 10 to 20 m, but that might take a few centuries. The collapse of agriculture would be the more immediate nightmare, along with floods of refugees from places that are no longer habitable. A majority of the world’s species would probably go extinct.

Being as I’ve chosen a mid-range ECS, I’d rate the odds of global catastrophe under this no-mitigation scenario around fifty-fifty. So we’ve got to ask ourselves one question:

Do we feel lucky?

Lest I be misunderstood: There is no climate analogue to the moment the jumper goes splat.

From Claire: An original version contained a sentence suggesting the Paris Agreement was, somehow, signed in the future. This was obviously a typo.

I trust readers know that by “quickly,” I mean “as these things go.”

From Claire: Who’d be crazy enough, I asked myself, to try to put a GPS collar on a polar bear? But how else would you know if their population is declining? Overcome by curiosity, I decided to find out. Wouldn’t you know it, there are people out there who are crazy enough to try to put GPS collars on polar bears. The problem is— surprise—the bears don’t like it. So the data is “deficient” because the vexed bears keep tearing off their collars and tossing them into the ice. Still, the effort to collar polar bears hasn’t been wasted, because it turns out tracking the discarded collars is a handy way to track the way the ice moves. The collars showed that ice-drift modeling data from the US National Snow and Ice Data Center underestimated the speed at which ice moves around in Hudson Bay. So we got something more useful out of that research grant than a bunch of poked bears.

Assumptions that are as likely wrong as correct:

1. A world 2 or 3C warmer would be worse off than now.

2. The are no natural negative feed backs that would reduce any warming from CO2 increases.

3. History: People were worse off in the Roman and Medieval Warming periods that were warmer than now.

4. History: People were better off during the Dark Ages and Little Ice Age that were colder than now.

5. Most of the warming since 1850 is the result of human emissions. History: Most of this warming occurred before humans began large scale emissions.

6. Sea rise is faster now than it was before CO2 emission rose. Actually, the gradual sea level rise that began when the Little Ice Age ended is proceeding at about the same pace as was naturally occurring before CO2 emissions rose. The variations are within the error margins of the measuring devices.

7. Droughts and flood are increasing. The data does not show an increase.

8. Tipping points exist. They did not happen when the climate was several degrees warmer earlier in this interglacial. Modelers can program their models to create them, but there is no evidence they exist in the real climate. They are a hypothesis without evidence.

9. Doubling CO2 to 800ppm would make a significant difference. The physics says that since warming effect of CO2 at 400ppm is saturated above 98.5%, Doubling to 800ppm would only increase the warming effect to around 99.5% in a very gradual rise by 2100. This small amount of potential warming by 2100 is not an emergency. A prosperous world will easily adjust to this slow motion change.

10. A few degrees C will destroy the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. The real danger to the ice is the dozens of active volcanic vents melting it from below. Reducing CO2 will have no effect on the volcanos.

11. The assumption of a linear relationship between CO2 levels and global temperature is unverified because it can’t be isolated from all the other factors. It is more likely, if you believe the physics experiments, an inverse logarithmic relationship. Every doubling has a much smaller effect than the prior doubling. Once saturation is reached, there is no more increase.

12. Methane is a strong greenhouse gas. Yes, but since water vapor has already saturated the IR frequencies methane absorbs, more methane cannot increase atmospheric temperature in any measurable way.

13. The climate has not been “steady” over the last 1000 years. The Medieval Warming Period was several degrees C warmer and the Little Ice Age was several degrees C cooler.

14. Climate models can successfully predict future climate. No way to know. They haven’t been very good at predicting the last 40 years.

15. The best mitigation might be to provide everyone with all the inexpensive electricity they need and increase the prosperity of all people as much as possible. A prosperous world can easily adjust any of the projected climate changes. Even the worst case IPCC guesses.

That is a lot of assuming by Dr X and others. I would prefer, at the government level, that decisions be based on data and the results of experiments, admitting that we don't know when we don't. Making these decisions based on the educated guesses of one set of experts (with or without a complicated computer program) is a formula for bad policy and misallocated resources.

By the way, I greatly appreciate Dr X putting himself out there for us to pick at and get the discussion going.

There are so many unknowns that people will be on all sides of this.

Being certain with few facts was a good strategy for survival in prehistoric times. That our brains are still instinctively wired this way makes us hard to get along with at times.

The problem is that while scientists like Dr. X are pulling the fire alarm, it's the politicians like John Kerry who are dispatching the hook and ladder. To me this suggests that either rapid technological advances will need to make it so overwhelmingly economically advantageous to limit greenhouse gas emissions or we're doomed to the global warming scenario that gives Dr. X nightmares. Effective governmental intervention either in the form of mandates or incentives are unlikely to be impactful.

Just last month in New York we saw a perfect example of the the hypocrisy and incompetence of environmental activists and the politicians who genuflect to them. For decades, New York City got 25 percent of its base load power from three reactors located at the Indian Point Power facility in suburban New York (about 30 miles north of the City). Obviously, the power generated was carbon-free and the plant had a spotless safety record.

Despite this, environmental activists have spent the better part of 30 years bitterly complaining that the plant was allowed to operate. Of course it's these same environmental activists who whine continuously about the threat posed by carbon emissions. A major champion of the activist community is New York's Governor, Andrew Cuomo (currently under an impeachment threat for alleged serial groping). Governor Cuomo has banned fracking in New York State, despite an ample supply of natural gas deposits and he has been a mortal enemy of those who want to build pipelines in New York. As a result of his Jihad against all things with the prefix "fossil," there are parts of the State where it is impossible to hook up new natural gas lines, which dramatically increases the cost of heating homes and making hot water because New York has amongst the highest electric rates in our nation. The excess cost, which can be onerous for working and middle class families could not matter less to the Governor, the state legislature or the latte-loving activist community.

Despite the fact that he allegedly worships at the altar of "clean energy" Governor Cuomo badgered Entergy (the owner of Indian Point) to close all three reactors located at the site. The final reactor was decommissioned in April.

As the reactors closed one by one, the electricity produced by Indian Point was replaced almost exclusively by electricity generated by natural gas. After the first reactor closed a few years back, the share of the State's power that came from gas generators jumped from 36 to 40 percent. With the closure of the other two reactors, New York State will probably get somewhere around 50 percent of its electricity from gas-powered plants during the winter. During the summer, when electricity use spikes, the share of gas generated electricity will surely jump to at least 55 percent and maybe 60 percent. If we have a particularly hot summer, there's plenty of peak-load capacity at the ready, but most of this generating capacity relies on oil.

Perhaps Dr. X will forgive skeptics from wondering why they should believe global warming activists and politicians who claim we face an extinction event when those same activists and politicians are not alarmed at the prospect of closing down a perfectly functional nuclear facility even at the cost of increasing green house gas emissions. The conclusion is inevitable, even the activists don't believe that reducing green house gasses is all that urgent; after all, they've successfully lobbied for a policy that significantly increases these emissions.

Although he wasn't the climate czar when the decision to close Indian Point was made, John Kerry was a well-known environmental activists who had fashioned himself as the Democratic Party's kibitzer-in-chief. We never heard him begging Governor Cuomo to keep Indian Point open. I don't remember hearing much from Bill McKibben, Greta Thunberg or any other well-know global warming activist either. Obviously, they must have felt that the large increase in green house gas emissions that inevitably arose from closing Indian Point was simply no big deal. If that's what leading climate change activists think, why should the rest of us believe anything else?

But here's the real irony; the environmentalists who lobbied for the shut down of Indian Point assure us that there's nothing to worry about. New York has great big plans to generate renewable energy. Off-shore wind farms and thousands of acres of solar arrays are on the way, we're told. Just a few years back, the State legislature mandated that by 2030, 50 percent of the State's electricity had to come from renewable sources. Last year our legislators decided that their goal wasn't ambitious enough and they raised the mandate to 70 percent.

Very little of this infrastructure has been built and anyone who believes that a State as overburdened by governmental bureaucracy as New York can pull it off by 2030 must be smoking some of the newly legal cannabis now for sale on almost every corner. If the fastidious Germans couldn't do it, New York doesn't have a chance.

But suppose by some miracle that we can. Suspend disbelief and contemplate the possibility that by 2030, New Yorkers will get 70 percent of their electricity from renewable sources. Does this mean that all the increased carbon emissions we contributed to the atmosphere in the intervening years as a result of the closing of Indian Point simply don't matter? Not if Dr. X is right. His argument suggests that those emissions are part and parcel of a looming disaster or, at least, a potential disaster.

Of course, 2030 is exactly 9 years away. That's exactly the point where John Kerry said we reach the point of no return. If we finally start making up for the emissions spewed into the atmosphere by the fossil-fuel burning generators that replaced Indian Point nine years from now, doesn't John Kerry think its too late? If we wait that long, and John Kerry is right, why bother trying?

With friends like environmental activists, do climate scientists really need enemies?

It seems highly unlikely that any of the goals proclaimed by climate scientists will be met. Shouldn't we start planning for the inevitable consequences?