The Energy Debate: A response to our readers

Some of you have asked why we host views with which you don't agree. Let us explain.

From Claire—Energy Week has prompted more outraged letters and “cancel my subscriptions” than anything else we’ve ever published.

First point: We cannot cancel your subscription unless you subscribe. If you’d like us to cancel your subscription, you must first do the needful:

Soon as you let us know you’ve paid, we’ll be happy to accomodate you.

Energy, it seems, is a controversial matter, as well it should be. It is important. Getting it wrong will have grave consequences. Getting it right may have grave consequences, too. There may be no good solutions, only less bad ones.

Among the world’s 7.8 billion people, there are genuinely vast differences of opinions about the best way to provide all of us with the energy we want or need. Some of these opinions are based on solid science and logic; some are not.

Some are based on a more subtle and subjective foundation, but not one we can blithely discount. For example, people vary greatly in their appetite for risk. What are the odds of climate change wiping out the entire living world? Let’s call this the world heats to omega, outlier-possibility scenario, or WHOOPS! If I believed it were one percent, I’d shrug. I was born in the nuclear era. I grew up believing and still firmly believe the odds are much higher we’ll wipe out the better part of the living world with our nuclear weapons.

If my doctor told me I was riddled from head to toe with metastatic cancer, I wouldn’t lose sleep worrying about catching syphilis from a toilet seat. Or perhaps I would, but it would be an obvious psychological displacement mechanism borne of intolerable anxiety about the real threat. In the same way, I’d find it hard to worry about a highly remote chance of the WHOOPS! if I believed that at this very second, a deranged man was holding a gun to my head.

And as it happens, I do believe that. Because it’s true.

Utterly malevolent madmen are, at this very moment, aiming dozens if not hundreds of hydrogen bombs at my head. If you live anywhere near a major population center, military base, or industrial facility, they’re aimed at your head, too. And your families’ heads. That is simply a fact about the world as it is now, a truth debated by no one.

The risk of nuclear war is much too high for someone with my appetite for risk, which is and has always been quite low. I always wear a seat belt. I quit smoking. I would not find a pickup game of Russian roulette thrilling under any circumstances. Because I believe the risk of an all-out nuclear exchange to be so high, I correspondingly believe that in policy making—although not in talking about policy—every good to which we aspire should be subordinated to the goal of not nuking each other.1

Of course, none of us agree about how best to do that. But I suspect most of us would agree that all-out thermonuclear war is an intolerable prospect, and it is not a future risk, but a present risk. Such a war could begin before you finish this sentence.

I’ve noticed, however, that other people seem to live with the risk of nuclear war quite cheerily. Perhaps they’re unaware of it. Many people, I’ve noticed, discuss this risk in the past tense, as if it had ended with the end of the Cold War. Absurd, of course, but I do think quite a few people believe the nukes somehow just went away, along with the geopolitical conflict. Or perhaps they figure the last time anyone got nuked was 1945, so it will probably never happen.2

Now, were you to persuade me the odds of WHOOPS! were closer to 25 percent, I’d worry. A one-in-four risk of wiping out civilization, along with every living creature on the planet, is just too high for me. It’s still lower, in my view, than the risk of all-out thermonuclear war, but it’s too high for me to accept. If I believed the number was 25 percent, it would get me agitated enough to say, “This risk should guide our energy policy.”

You may be different in your tolerance of risk. You may feel the odds are still against WHOOPS!, so why not bet it won’t happen? That’s how any casino worthy of the name would bet, and the House always wins. Or perhaps, like me, you may worry that actions we take to mitigate this risk might raise an even greater risk. Suppose, for example, you think, “Sure, solar might work, but that’s still speculative. We know nuclear power works. It’s the only sure way to avoid WHOOPS! So we must convert the world to nuclear energy as quickly as possible.” By implication, then, to mitigate the risk of WHOOPS! we have to proliferate nuclear technology. There’s some important non-WHOOPS! risk there to consider, too.

So there are many reasons for there to be such divergent opinions about the best way to provide energy to the whole world. Some are grounded in solid science and a realistic grasp of what is feasible, technologically and politically. Some are not. In debating these issues, we hope here at least to sort out the difference between the former and the latter.

Some of the differences, however, are grounded in temperament or moral sensibility. We may well find in the end that we simply disagree about acceptable levels of risk, or whether the benefits of a policy are so desirable that they outweigh those risks. Some of us, for example, think prosperity is exceptionally important. Others may conclude the risks that come with prosperity are too high. They would rather reduce their standards of living—or better still, someone else’s—and lower the risk.

If we assess risks coherently, in their totality—a very tricky thing to do—we may find that in the end, what divides us is temperament. Some of us would rather live in a high-risk, high-reward world. Others would prefer to live in squalor and poverty, under the Chinese boot, than take any risk of contributing to WHOOPS!

And no, that is not an insane view. Risking WHOOPS! is a hell of a hubristic thing to do. If it all goes horribly wrong, are you quite sure you want to answer for that one in the Afterlife?

So it is a genuinely difficult question. Just to begin to have a wise or an informed judgement requires considering many points of view. But in a democracy, the people are sovereign. So we have to try.

That’s why we’re having a debate.

Thus my response to enraged readers—and you know who you are, and you are not alone—who have written recently to ask, “Claire, how could you have published that outrageous dreck? Don’t you realize the author is insane?” (By the way, it’s not me but the Cosmopolitan Globalists who publish these pieces, though it’s fine if you direct your ire toward me.3 Direct all praise, however, to the team.) What’s interesting is that the irate cancel-my-subscriptions have come in after every essay we’ve published on the topic, in roughly equal numbers.

You anti-solar fanatics are freaks, by the way. If you want to cancel your subscription because you think solar panels are the Devil’s Handmaidens, be our guest, but again: We cannot cancel your subscription unless you subscribe.

Please, give us both the satisfaction.

According to these letters, we are either tools of the fossil fuel lobby, Malthusian génocidaires, elitists who want to put blue collar Americans out of work, enemies of democracy, or unable to “think critically.” (The author of the latter comment directed us to a website he viewed as stellar example of critical thinking. It wasn’t.)

All of this geschrei because we’ve been having a sober, technical, polite, and respectable debate? About a truly important question?

What does this suggest? I don’t know the exact provenance of all of these letters, but they’re written in English, so I suspect most came either from the Anglophone world or those with a great deal of contact with it. To me—perhaps I am wrong—it suggests we’re rapidly losing the skills required for making liberal democracy flourish. But maybe this conclusion is an example of my confirmation bias. That’s actually why we founded the Cosmopolitan Globalist, after all. We firmly believed this to be so.

So let me explain, once again: We believe in debate.

This is a debate

Perhaps we inadequately stressed, “This is a debate,” though to be honest, I don’t know what more we could have done than calling it, “THE GREAT DEBATE,” setting up separate forums for debating, explaining that people would be judged for their debating skills, and putting up a “DEBATE” logo with every post.

We even warned readers they’d have to read views they find intolerable. But we reassured them that contrary to contemporary wisdom, contact with a view they disliked would not kill them, nor even cause them injury, because speech, in a very significant way, is unlike violence. We meant to demonstrate the latter point decisively, by the way, if obiter dicta. Please raise your hand if as a result of reading any essay published here you have suffered bruises, contusions, lacerations, bone fractures, brain injury, solid organ injuries, tympanic membrane rupture, or a hemorrhage. Pulmonary barotrauma, anyone? No? There you go.

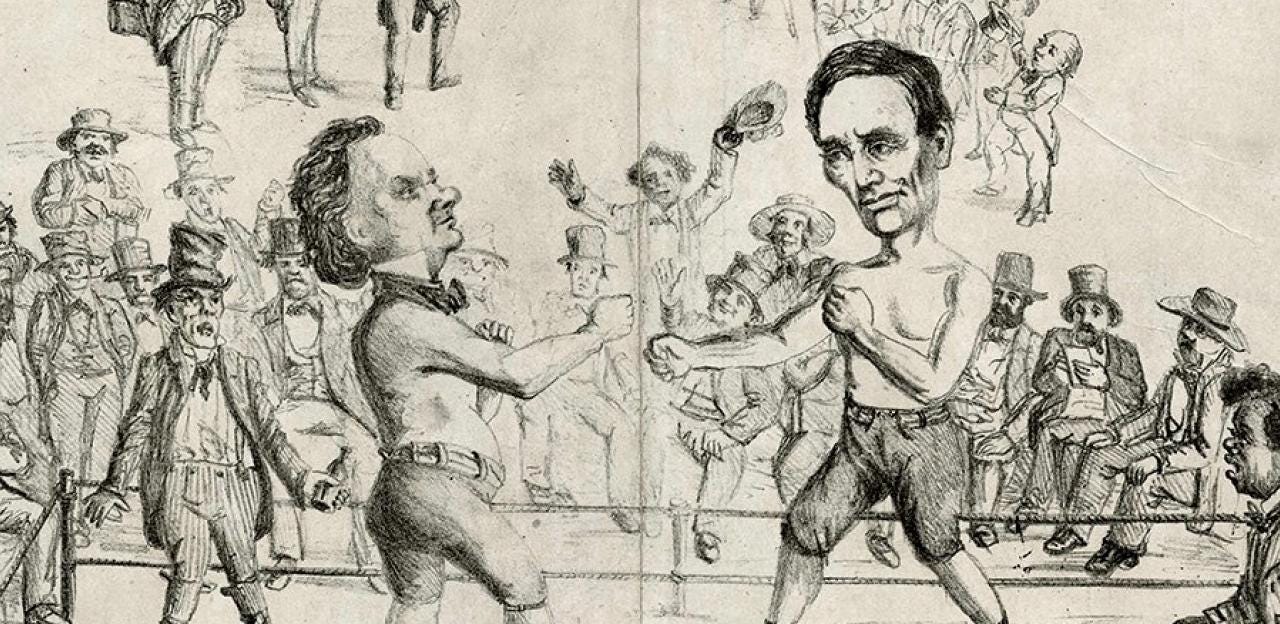

A debate involves a formal exchange of ideas among people with different, hostile views. There is no point in having a debate among people who basically agree with each other and are just ironing out the kinks. That is what we might call un cercle des branleurs, and branleurs apart, no one finds that interesting to watch. Nor is there any point inviting distinguished scientists and writers to waste their time doing battle with straw men. We sought compelling—and sincere—advocates of prominent but disparate views on this subject. Every writer we’ve featured or will feature in this debate represents a view widely held by people the world around. We excluded some opinions because they’re just silly; we did not, for example, seek the views of cranks who cling to a non-heliocentric theory of the solar system. But every view we’ve published is one with which many of your fellow citizens agree.

Alas, our siloed media now allows people to hear only the views of people who agree with them. This is terrible. It is not a catastrophe on the order of nuclear war, but it genuinely warrants alarm. It has made us ciphers to our fellow citizens. Democracies are now bitterly divided, to the point that French generals issue minatory warnings about civil war and Americans are at risk of losing the Union. All of this is bad, to be sure, but what’s worse is that my God, these circumstances have made us all so much stupider.

Whether the climate crisis is such that it demands radical energy policies such as the ones Alex and Ben proposed yesterday is now the big debate in the West. Yet very few people have any idea what intelligent exponents of the opposite view actually believe. They understand them only as they’ve been mediated—and caricatured—by enemies of those views. That’s no way to run a liberal democracy.

There are some views we won’t host on the pages of the Cosmopolitan Globalists. No enemies of the Open Society. No Nazis, communists, Islamists, Catholic integralists. No one whose views lead to a Popperian paradox of tolerance.

But by and large, we see no reason to declare any powerful current in public opinion anathematized and judged a form of heresy. If you disagree with our writers, we’ve set up a forums where you can explain why you disagree with them. We’ve done this because we welcome debate. That’s why we’re having one.

In short: Hell no, we’re not cancelling our writers. Cancel your own damned subscription instead.

Nuclear deterrence is a complicated subject for another day, but suffice to say that even if you’d rather be red than dead, it’s an incredibly stupid thing to say. It increases the likelihood you’ll wind up red, dead, or both.

The last time there was a cataclysmic global pandemic was 1918. I just checked: the phrase “once-in-a-century-pandemic” came into widespread use in the year 2020. Careful with these assumptions. Seriously.

Not as if I just lost my cat or anything, you jerks.

I'm copying this comment from the forum where I posted it in case anyone missed it. (The forum was the one where we asked people to debate the proposition, "The Green worldview does more harm than good.) The debate going on there is worth your time if you haven't read it. I've corrected the typos in the original.

"Note from Claire (not a debate point at all). I woke up to see this and was as pleased to read it as I was displeased, yesterday, to wake up to yet more email demanding that I strike Ben, Owen's father, or a number of our other contributors from our ranks, delete their contributions, declare them heretics, and ostracize from civilized society as violent thought-criminals--all because they'd offered polite, well-written, thoughtful, and carefully-argued essays or thoughts about the future of energy. These emails worry me far more than the energy debate itself.

I agree that the consequences of getting our energy policy wrong could be exceptionally serious; in the very worst case, they could end life on earth; in the somewhat-worse but still exceptionally serious case, they could impoverish the free world or cripple the developing world.

But in the long run we'll all be dead. In the short term, we now have a gravely worrying problem: It has become a cultural norm in the West (I think all these letter-writers were Westerners, from the tone and style) to *demand* that no one express a view with which he or she disagrees. People do not seem to think twice about doing so. All too few instinctively think, "It is grotesque, and highly inappropriate in a free society, even to request this, no less demand it."

The problem is cross-partisan, and it afflicts far more people than I'd realized. And this is *Energy* Week, for Heaven's sake, not Transgender Week. We're a bunch of policy wonks nerding out over here; we're not deliberately wading into some culture war zone for clicks. I would never have dreamt this subject would give rise to the kind of hysteria it has. So thank you, all of you, for reminding not only me but other readers what a normal, healthy response to disagreement is supposed to look like in a liberal democracy. It put me in a good mood to begin my day."

I also realized that chastising all of our readers for letters sent to me by no more than a dozen-odd readers was unnecessary, even silly; after all, presumably those who declared they'd never read another word we published didn't see it. (Though I suspect they did: The people who send those letters have a strange, stalker's obsession with this newsletter.) But I suspect those of you who agree with me enjoyed the statement of principle. And I'm so glad we also have so many *more* people here who think that's a principle worth vigorously defending.

We will defeat the cancellers, snowflakes, hysterics, and thought police. There are more of us than there are of them, and if we push back on them, hard, we can establish the norm: Ours is an open society, and the only appropriate response to speech we don't like is more speech and better speech.

"Perhaps we inadequately stressed, “This is a debate,” "

Well, you know. Maybe the term "debate" has lost some of its utility. After all, it was no less a light than Kamala Harris, on being asked on a late night talk show why she lied so in a then-recently concluded Progressive-Democratic Party Presidential primary debate, responded chucklingly, "It was a debate."

[/snark]

Give 'em hell, Claire. The ones who are afraid of debate are the ones with the least to contribute to one. Or ignore them altogether; they're a waste of your time.

And, again, my sympathies and condolences for Daisy and for you.

Eric Hines