Yesterday morning, an AI-generated image of an explosion at the Pentagon went viral on social media. Multiple news sources reported it as real—including Russia Today and a blue-checked account on Twitter that claimed to be Bloomberg, but wasn’t. (Another Musk-policy triumph.) The S&P 500 briefly plummeted.

As you may have noticed, I’ve been taking a short break, this for two reasons. The first is that one of my oldest and dearest friends is in Paris for a few days, and she and I so rarely see each other that I want to make the most of every minute she’s here.1 The second is that I realized—quite a bit later than I should have, really—that no story in the world could be more important than the ongoing revolution in AI.

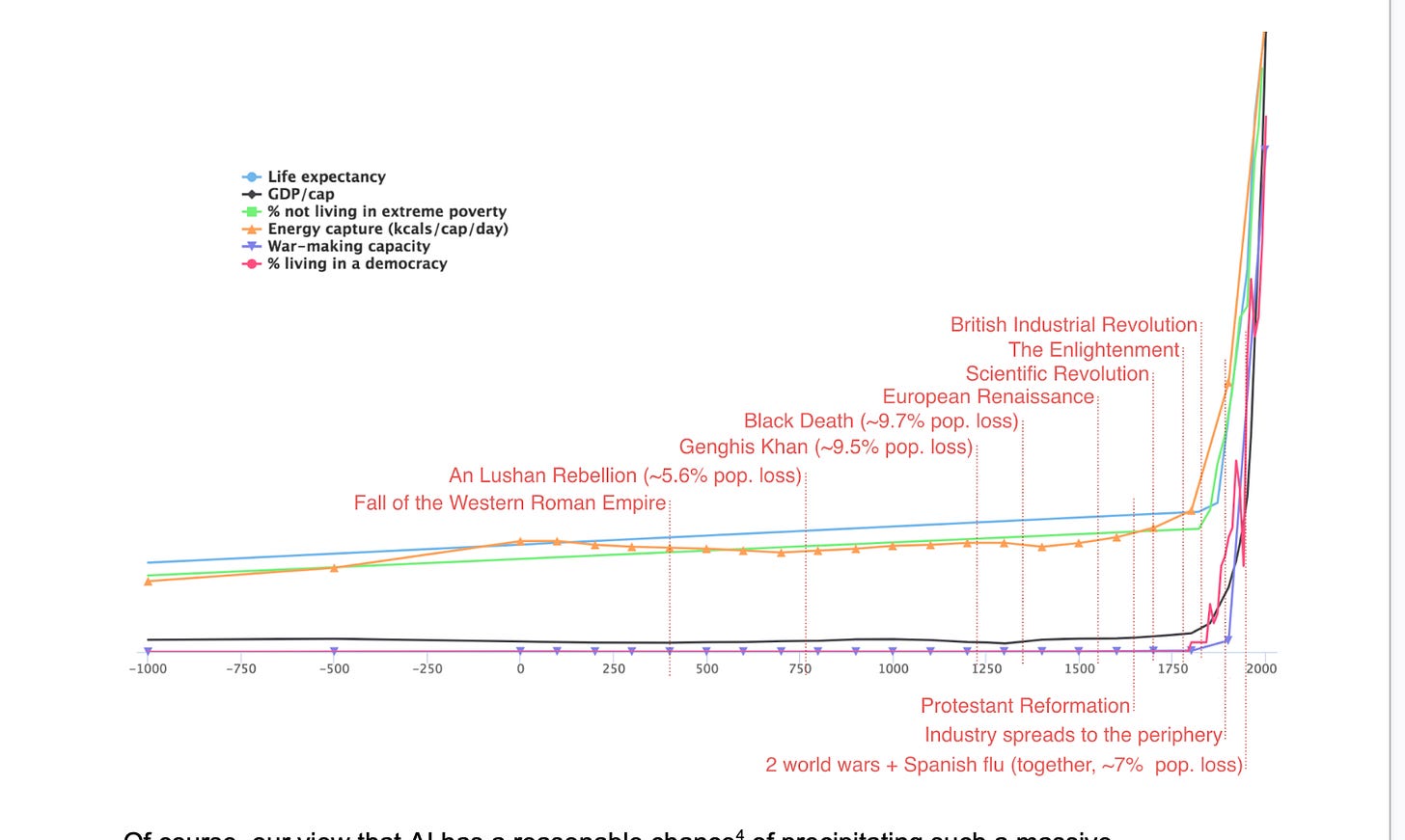

It makes no sense for CG to ignore this, given it’s not only the most important story in the world, but very likely the most important story of the century, possibly the most important of the millennium, and maybe even the most important in the history of our planet. I realized we needed to write about this—and write quite a bit, at that—which meant I need to learn about it.

The topic is new to me, so it’s taking me a few days—and a few days is all it took to persuade me the release of ChatGPT4 is an event on a par with the detonation of the first atomic weapon. It’s “just” a stochastic parrot in the same way that Little Boy and Fat Man were “just” explosive devices.

To judge from the quality of recent Congressional hearings on the topic, however, our legislators haven’t a clue what we’re confronting and are in no way inclined to control it—or capable of it, which means Sam Altman is now the most powerful man in the world and our future is in his hands. That marks a rather significant change to the way we govern ourselves, which alone would be worthy of more than a few days’ thought here at CG.

We’ll be discussing this, from many angles, in the coming week. For today, I’ll share my reading list with you. Would you like to read it with me? I know some of you are already intimately familiar with this body of thought, but I assume that many of you, like me, are approaching this as novices. I promise you that learning the basics will be well worth the investment of your time: I haven’t studied anything with such interest in a long time.

If we all get up to speed, it will give us the chance to have a much more interesting conversation about this in the coming week. Without understanding at least as much as I’ve suggested here, I think it’s all but impossible to assess what we’re now hearing about it. The senators and journalists who’ve been interviewing Sam Altman recently have clearly been unprepared. (After spending a week studying this, I’m far more prepared than the US Senate was, which infuriates me. Don’t they have staff to prepare them for these things? Why didn’t they do the minimum amount of reading required to hold such significant hearings? It’s their job, for God’s sake.)

Our tech companies shouldn’t be allowed to evade scrutiny because no one’s willing to spend a few hours figuring out what they’re doing—especially because there’s a non-trivial chance they’re going to kill us all—but they are, anyway.2

This week, I’ll be inviting people to write for us and come on the podcast to discuss the risks, promises, and dangers of AI. It would be good to be able to assume that we all have a grasp on the basics—how ChatGPT works, what we mean when we discuss the alignment problem, why prudent people are dumbfounded by the recklessness of our tech companies—and needn’t spend time reviewing them.

I’ll also provide a summary of the reading below (once I’ve finished it), but I do hope you’ll read it with me. Some of it is a bit technical, but don’t be put off. If I can understand it, anyone can. (And if you come across something that doesn’t make sense, ChatGPT will be only too happy to explain it to you.)

AI: An introductory reading list

Please feel free to contribute to this.

Pause Giant AI Experiments: An Open Letter. We call on all AI labs to immediately pause for at least six months the training of AI systems more powerful than GPT-4:

AI systems with human-competitive intelligence can pose profound risks to society and humanity, as shown by extensive research and acknowledged by top AI labs. As stated in the widely-endorsed Asilomar AI Principles, Advanced AI could represent a profound change in the history of life on Earth, and should be planned for and managed with commensurate care and resources. Unfortunately, this level of planning and management is not happening, even though recent months have seen AI labs locked in an out-of-control race to develop and deploy ever more powerful digital minds that no one – not even their creators – can understand, predict, or reliably control.

Contemporary AI systems are now becoming human-competitive at general tasks and we must ask ourselves: Should we let machines flood our information channels with propaganda and untruth? Should we automate away all the jobs, including the fulfilling ones? Should we develop nonhuman minds that might eventually outnumber, outsmart, obsolete and replace us? Should we risk loss of control of our civilization? Such decisions must not be delegated to unelected tech leaders. Powerful AI systems should be developed only once we are confident that their effects will be positive and their risks will be manageable. This confidence must be well justified and increase with the magnitude of a system’s potential effects. OpenAI’s recent statement regarding artificial general intelligence states that “At some point, it may be important to get independent review before starting to train future systems, and for the most advanced efforts to agree to limit the rate of growth of compute used for creating new models.” We agree. That point is now.

Pausing AI developments isn’t enough. We need to shut it all down:

The key issue is not “human-competitive” intelligence (as the open letter puts it); it’s what happens after AI gets to smarter-than-human intelligence. Key thresholds there may not be obvious, we definitely can’t calculate in advance what happens when, and it currently seems imaginable that a research lab would cross critical lines without noticing.

Many researchers steeped in these issues, including myself, expect that the most likely result of building a superhumanly smart AI, under anything remotely like the current circumstances, is that literally everyone on Earth will die. Not as in “maybe possibly some remote chance,” but as in “that is the obvious thing that would happen.” It’s not that you can’t, in principle, survive creating something much smarter than you; it’s that it would require precision and preparation and new scientific insights, and probably not having AI systems composed of giant inscrutable arrays of fractional numbers. …

To visualize a hostile superhuman AI, don’t imagine a lifeless book-smart thinker dwelling inside the internet and sending ill-intentioned emails. Visualize an entire alien civilization, thinking at millions of times human speeds, initially confined to computers—in a world of creatures that are, from its perspective, very stupid and very slow. A sufficiently intelligent AI won’t stay confined to computers for long. In today’s world you can email DNA strings to laboratories that will produce proteins on demand, allowing an AI initially confined to the internet to build artificial life forms or bootstrap straight to postbiological molecular manufacturing.

Claire—well worth your time to hear him out completely. His most insistent point is chilling in its implications: We have no idea what is taking place inside these systems and no obvious way to learn this quickly. The problem is not insoluble; but it is very, very difficult.

“The Godfather of AI” leaves Google and warns of danger ahead. For half a century, Geoffrey Hinton nurtured the technology at the heart of chatbots like ChatGPT. Now he worries that the tech giants are locked in a competition that might be impossible to stop—threatening humanity:

… Down the road, he is worried that future versions of the technology pose a threat to humanity because they often learn unexpected behavior from the vast amounts of data they analyze. This becomes an issue, he said, as individuals and companies allow AI systems not only to generate their own computer code but actually run that code on their own. And he fears a day when truly autonomous weapons—those killer robots—become reality. “The idea that this stuff could actually get smarter than people — a few people believed that,” he said. “But most people thought it was way off. And I thought it was way off. I thought it was 30 to 50 years or even longer away. Obviously, I no longer think that.”

What really made Geoffrey Hinton into an AI doomer. The AI pioneer is alarmed by how clever the technology he helped create has become:

Hinton says AI is advancing more quickly than he and other experts expected, meaning there is an urgent need to ensure that humanity can contain and manage it. He is most concerned about near-term risks such as more sophisticated, AI-generated disinformation campaigns, but he also believes the long-term problems could be so serious that we need to start worrying about them now.

When asked what triggered his newfound alarm about the technology he has spent his life working on, Hinton points to two recent flashes of insight.

One was a revelatory interaction with a powerful new AI system—in his case, Google’s AI language model PaLM, which is similar to the model behind ChatGPT, and which the company made accessible via an API in March. A few months ago, Hinton says he asked the model to explain a joke that he had just made up—he doesn’t recall the specific quip—and was astonished to get a response that clearly explained what made it funny. “I’d been telling people for years that it’s gonna be a long time before AI can tell you why jokes are funny,” he says. “It was a kind of litmus test.” Hinton’s second sobering realization was that his previous belief that software needed to become much more complex—akin to the human brain—to become significantly more capable was probably wrong. PaLM is a large program, but its complexity pales in comparison to the brain’s, and yet it could perform the kind of reasoning that humans take a lifetime to attain.

Claire—that’s one of the things that triggered my alarm, too—the realization that ChatGPT understands what makes jokes funny. The other thing? This:

Claire—really give that one some thought.

Current and near-term AI as a potential existential risk factor:

There is a substantial and ever-growing corpus of evidence and literature exploring the impacts of Artificial intelligence technologies on society, politics, and humanity as a whole. A separate, parallel body of work has explored existential risks to humanity, including but not limited to that stemming from unaligned Artificial General Intelligence. In this paper, we problematize the notion that current and near-term artificial intelligence technologies have the potential to contribute to existential risk by acting as intermediate risk factors, and that this potential is not limited to the unaligned AGI scenario. We propose the hypothesis that certain already-documented effects of AI can act as existential risk factors, magnifying the likelihood of previously identified sources of existential risk. Moreover, future developments in the coming decade hold the potential to significantly exacerbate these risk factors, even in the absence of artificial general intelligence. Our main contribution is a (non-exhaustive) exposition of potential AI risk factors and the causal relationships between them, focusing on how AI can affect power dynamics and information security. This exposition demonstrates that there exist causal pathways from AI systems to existential risks that do not presuppose hypothetical future AI capabilities.

Orthodox versus Reform AI Risk:

Orthodox AI-riskers tend to believe that humanity will survive or be destroyed based on the actions of a few elite engineers over the next decade or two. Everything else—climate change, droughts, the future of US democracy, war over Ukraine and maybe Taiwan—fades into insignificance except insofar as it affects those engineers. We Reform AI-riskers, by contrast, believe that AI might well pose civilizational risks in the coming century, but so does all the other stuff, and it’s all tied together. An invasion of Taiwan might change which world power gets access to TSMC GPUs. Almost everything affects which entities pursue the AI scaling frontier and whether they’re cooperating or competing to be first.

Orthodox AI-riskers believe that public outreach has limited value: most people can’t understand this issue anyway, and will need to be saved from AI despite themselves. We Reform AI-riskers believe that trying to get a broad swath of the public on board with one’s preferred AI policy is something close to a deontological imperative.

Orthodox AI-riskers worry almost entirely about an agentic, misaligned AI that deceives humans while it works to destroy them, along the way to maximizing its strange utility function. We Reform AI-riskers entertain that possibility, but we worry at least as much about powerful AIs that are weaponized by bad humans, which we expect to pose existential risks much earlier in any case.

Orthodox AI-riskers have limited interest in AI safety research applicable to actually-existing systems (LaMDA, GPT-3, DALL-E2, etc.), seeing the dangers posed by those systems as basically trivial compared to the looming danger of a misaligned agentic AI. We Reform AI-riskers see research on actually-existing systems as one of the only ways to get feedback from the world about which AI safety ideas are or aren’t promising.

Orthodox AI-riskers worry most about the “FOOM” scenario, where some AI might cross a threshold from innocuous-looking to plotting to kill all humans in the space of hours or days. We Reform AI-riskers worry most about the “slow-moving trainwreck” scenario, where (just like with climate change) well-informed people can see the writing on the wall decades ahead, but just can’t line up everyone’s incentives to prevent it.

Orthodox AI-riskers talk a lot about a “pivotal act” to prevent a misaligned AI from ever being developed, which might involve (e.g.) using an aligned AI to impose a worldwide surveillance regime. We Reform AI-riskers worry more about such an act causing the very calamity that it was intended to prevent.

Orthodox AI-riskers feel a strong need to repudiate the norms of mainstream science, seeing them as too slow-moving to react in time to the existential danger of AI. We Reform AI-riskers feel a strong need to get mainstream science on board with the AI safety program.

Orthodox AI-riskers are maximalists about the power of pure, unaided superintelligence to just figure out how to commandeer whatever physical resources it needs to take over the world (for example, by messaging some lab over the Internet, and tricking it into manufacturing nanobots that will do the superintelligence’s bidding). We Reform AI-riskers believe that, here just like in high school, there are limits to the power of pure intelligence to achieve one’s goals. We’d expect even an agentic, misaligned AI, if such existed, to need a stable power source, robust interfaces to the physical world, and probably allied humans before it posed much of an existential threat.

If AI scaling is to be shut down, let it be for a coherent reason:

Would your rationale for this pause have applied to basically any nascent technology—the printing press, radio, airplanes, the Internet? “We don’t yet know the implications, but there’s an excellent chance terrible people will misuse this, ergo the only responsible choice is to pause until we’re confident that they won’t?”

Why six months? Why not six weeks or six years?

When, by your lights, would we ever know that it was safe to resume scaling AI—or at least that the risks of pausing exceeded the risks of scaling? Why won’t the precautionary principle continue for apply forever?

Were you, until approximately last week, ridiculing GPT as unimpressive, a stochastic parrot, lacking common sense, piffle, a scam, etc.—before turning around and declaring that it could be existentially dangerous? How can you have it both ways? If, as sometimes claimed, “GPT-4 is dangerous not because it’s too smart but because it’s too stupid,” then shouldn’t GPT-5 be smarter and therefore safer? Thus, shouldn’t we keep scaling AI as quickly as we can … for safety reasons? If, on the other hand, the problem is that GPT-4 is too smart, then why can’t you bring yourself to say so?

Claire—it does not fill me with confidence that the fatuous arguments above were made by one of Open AI’s safety researchers.

The AI arms race is changing everything:

… As companies hurry to improve the tech and profit from the boom, research about keeping these tools safe is taking a back seat. In a winner-takes-all battle for power, Big Tech and their venture-capitalist backers risk repeating past mistakes, including social media’s cardinal sin: prioritizing growth over safety. While there are many potentially utopian aspects of these new technologies, even tools designed for good can have unforeseen and devastating consequences. This is the story of how the gold rush began—and what history tells us about what could happen next.

The dangers of stochastic parrots. Can language models be too big?

Is power-seeking AI an existential risk?

This report examines what I see as the core argument for concern about existential risk from misaligned artificial intelligence. I proceed in two stages. First, I lay out a backdrop picture that informs such concern. On this picture, intelligent agency is an extremely powerful force, and creating agents much more intelligent than us is playing with fire—especially given that if their objectives are problematic, such agents would plausibly have instrumental incentives to seek power over humans. Second, I formulate and evaluate a more specific six-premise argument that creating agents of this kind will lead to existential catastrophe by 2070. On this argument, by 2070:

It will become possible and financially feasible to build relevantly powerful and agentic AI systems;

There will be strong incentives to do so;

It will be much harder to build aligned (and relevantly powerful/agentic) AI systems than to build misaligned (and relevantly powerful/agentic) AI systems that are still superficially attractive to deploy;

Some such misaligned systems will seek power over humans in high-impact ways;

This problem will scale to the full disempowerment of humanity; and

Such disempowerment will constitute an existential catastrophe.

I assign rough subjective credences to the premises in this argument, and I end up with an overall estimate of ~5 percent that an existential catastrophe of this kind will occur by 2070. (May 2022 update: since making this report public in April 2021, my estimate here has gone up, and is now at >10 percent.)

Here’s the article above in a video presentation:

The alignment problem from a deep learning perspective:

Within the coming decades, artificial general intelligence may surpass human capabilities at a wide range of important tasks. We outline a case for expecting that, without substantial effort to prevent it, AGIs could learn to pursue goals which are undesirable (i.e., misaligned) from a human perspective. We argue that if AGIs are trained in ways similar to today’s most capable models, they could learn to act deceptively to receive higher reward, learn internally-represented goals which generalize beyond their training distributions, and pursue those goals using power-seeking strategies. We outline how the deployment of misaligned AGIs might irreversibly undermine human control over the world, and briefly review research directions aimed at preventing this outcome.

Our bottom-line judgment is that language models will be useful for propagandists and will likely transform online influence operations. Even if the most advanced models are kept private or controlled through application programming interface (API) access, propagandists will likely gravitate towards open-source alternatives and nation states may invest in the technology themselves.

This curriculum is designed to be an efficient way for you to gain foundational knowledge for doing research or policy work on the governance of transformative AI (TAI)—AI with impacts at least as profound as those of the industrial revolution. It covers some research up to 2022 on why TAI governance may be important to work on now, what large-scale risks TAI poses, and which actors will play key roles in steering TAI’s trajectory, as well as what strategic considerations and policy tools may influence how these actors will or should steer. Existing work on these subjects is far from comprehensive, settled, or watertight, but it is hopefully a useful starting point.

The game changer. AI could contribute up to US$15.7 trillion to the global economy in 2030, more than the current output of China and India combined. Of this, US$6.6 trillion is likely to come from increased productivity and US$9.1 trillion is likely to come from consumption-side effects.

An early look at the labor market impact potential of large language models:

We investigate the potential implications of large language models (LLMs), such as Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPTs), on the US labor market, focusing on the increased capabilities arising from LLM-powered software compared to LLMs on their own. Using a new rubric, we assess occupations based on their alignment with LLM capabilities, integrating both human expertise and GPT-4 classifications. Our findings reveal that around 80 percent of the US workforce could have at least 10 percent of their work tasks affected by the introduction of LLMs, while approximately 19 percent of workers may see at least 50 percent of their tasks impacted. We do not make predictions about the development or adoption timeline of such LLMs. The projected effects span all wage levels, with higher-income jobs potentially facing greater exposure to LLM capabilities and LLM-powered software. Significantly, these impacts are not restricted to industries with higher recent productivity growth. Our analysis suggests that, with access to an LLM, about 15 percent of all worker tasks in the US could be completed significantly faster at the same level of quality. When incorporating software and tooling built on top of LLMs, this share increases to between 47 and 56 percent of all tasks. This finding implies that LLM-powered software will have a substantial effect on scaling the economic impacts of the underlying models. We conclude that LLMs such as GPTs exhibit traits of general-purpose technologies, indicating that they could have considerable economic, social, and policy implications.

★ What is ChatGPT doing … and why does it work?

Claire—this is the best explanation I’ve read.

Sparks of Artificial General Intelligence: Early experiments with GPT-4:

Artificial intelligence researchers have been developing and refining large language models that exhibit remarkable capabilities across a variety of domains and tasks, challenging our understanding of learning and cognition. The latest model developed by OpenAI, GPT-4, was trained using an unprecedented scale of compute and data. In this paper, we report on our investigation of an early version of GPT-4, when it was still in active development by OpenAI. We contend that (this early version of) GPT-4 is part of a new cohort of LLMs (along with ChatGPT and Google's PaLM for example) that exhibit more general intelligence than previous AI models. We discuss the rising capabilities and implications of these models. We demonstrate that, beyond its mastery of language, GPT-4 can solve novel and difficult tasks that span mathematics, coding, vision, medicine, law, psychology and more, without needing any special prompting. Moreover, in all of these tasks, GPT-4’s performance is strikingly close to human-level performance, and often vastly surpasses prior models such as ChatGPT. Given the breadth and depth of GPT-4’s capabilities, we believe that it could reasonably be viewed as an early (yet still incomplete) version of an artificial general intelligence system. In our exploration of GPT-4, we put special emphasis on discovering its limitations, and we discuss the challenges ahead for advancing towards deeper and more comprehensive versions of AGI, including the possible need for pursuing a new paradigm that moves beyond next-word prediction. We conclude with reflections on societal influences of the recent technological leap and future research directions.

Watch, at least, the first two minutes of this talk: Sam Harris makes an important point about the failure of intuition to which this technology gives rise.

You know Judith, actually—she’s written for us here, and I’ve written about her, too. You’ve even seen a video of us together:

On Uri Buri (Here you can see an old video of Judith and me road-tripping together in Israel and parenthetically doing a bit of journalism.)

Life-changing beauty hacks: How to procrastinate better.

Here’s an example of a bad interview with Altman. I don’t ever want to hear a journalist say, “I don’t understand this, but smart people say … ” If you don’t know enough to conduct an interview, you shouldn’t be conducting it.

I'll be honest Claire I get overwhelmed with data dumps like this. That being said, I've resubscribed because AI is terrifying to me and I know that you will dive deeper than any journalist, publication, ANYONE. You are the most thorough journalist I think exists right now.

Keep it up. I deeply value your work, though my attention span cannot handle it all. Like trying to drink a swimming pool. I will work on getting better at absorbing information.

World leaders on AI right now:

"What even is this, in specific language please? Okay you’re building a — *checks notes* — god? Very nice, what does that mean in terms of copyright violation? This will be bad for jobs but maybe also good, yes? Finally, and most importantly of all, why are you asking us to regulate something we don’t yet understand?"

https://twitter.com/PirateWires/status/1661008530860810243?t=ACn8n6ETQe1T9yfH__Nk5Q&s=19