From Claire—Today you’ll be receiving more than one newsletter. Owing to what Substack called a network error, yesterday’s newsletter wasn’t despatched until today. I don’t know why, but the problem seems to have resolved itself. Since we’re sending out two newsletters today, I couldn’t see any reason not to send a third. This one has nothing to do with Energy Week.

You may recall that our special correspondent to the Cosmopolitan Globalist in Israel, Judith Levy, is also my very dear friend. Here are a few videos of us together, taken ten years ago when we went on a road trip in Israel, during which we parenthetically did some journalism.

In the video below, we’re en route to Abu Ghosh, an Arab-Israeli village about ten kilometers west of Jerusalem, famous for its culinary delights. Judith took me there so we could sample the hummus, but also so I could speak to people such as the gentleman featured in the videos below, Ibrahim. I don’t speak Hebrew or Arabic, so Judith translated for me. If you’ve been following the news, you’ll see how relevant that conversation remains. The only thing that’s changed is my face.

I miss Judith terribly.

Those of you old enough to remember the First Gulf War will remember how it turned CNN into a sensation. She and I were studying at Oxford at the time. Everyone was glued to CNN, which we gathered to watch in the common room around a single small single television. This was the first time any of us—any civilian—had seen television coverage like this of a war, with footage of missiles hitting their targets taken from the missile’s perspective, and trails of dueling Scud and Patriot missiles hurtling through the night sky. Spliced through this was footage filmed through night-vision equipment; the effect was futuristic, making war look like a movie or a video game. We weren’t savvy enough to understand this was the intended effect; this kind of coverage was entirely new. We were gripped to the news, terrified.

Then as now, it was easier and safer for journalists to work in Israel than Iraq, so news from Israel was more widely reported than one might expect. Although Israel wasn’t a belligerent, Saddam Hussein launched missile after missile in the general direction of Tel Aviv, hoping to flip states that supported the coalition (because they didn’t think it right for Iraq invade its neighbors) but might be persuaded to switch sides (because they thought it helpful to kill Jews). Israelis feared the missiles might carry chemical or biological payloads. The government told them to build themselves sealed rooms from plastic and duct tape. Civilians were required to keep gas masks with them at all times, including on the beach. For babies, there was a government-issued device like a plastic birdcage.

Some hapless American journalist was interviewing a large Israeli family when the incoming-missile siren began to blare. The family began frantically trying to put on their masks, squeeze their babies into their birdcages, and stuff themselves into the plastic room. As the siren screamed, Bright Eyes from the Network decided unaccountably it would be appropriate for her to shove her microphone right into the face of the elderly paterfamilias. “So!” she said. How does this make you feel?”

He thought it over for a moment. “Not bad!” he replied. “Not bad! It’s not often we get the whole family together!”

I’ve thought of that story every time since when I’ve seen in the news that missiles are raining down on Israelis or Israelis are raining down missiles. I always want to know if Judith and her family are okay, but how do you ask that, exactly? Of course they’re not okay.

I nonetheless wrote to Judith to ask if she’s okay. It turns out she’s not in Israel right now. She had picked this week to visit her father in Florida. They hadn’t seen each other since the beginning of the pandemic. So she’s following the ghastly news from far away, which is its own special kind of agony.

I asked if she was okay. “I understand they want to try to hit incoming flights over Ben-Gurion, so an Ambien might be in order on my return trip,” she replied.

I asked her if she would consider writing about these events for us. She replied:

Thank you for the offer about writing something for CG. Can I think about it? I really am trying to avoid the news as best I can—I just check in with JPost from time to time during the day to hear the latest, but am doing my best not to see the other headlines. It’s too upsetting.

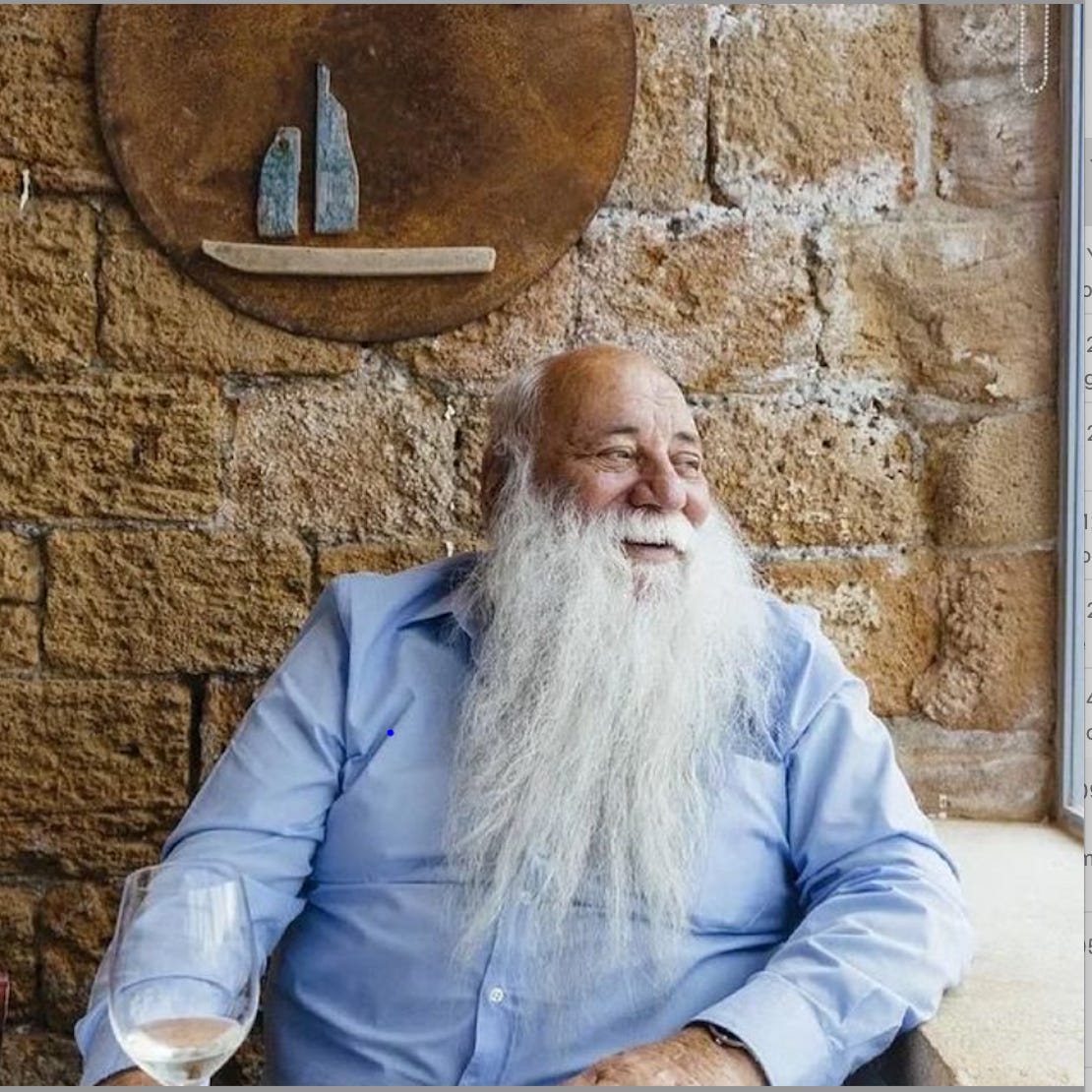

Before my embargo, while I was still looking at more headlines than just the what’s-happening-right-now ones, I went fucking ballistic (on the inside, of course) when I read that they had torched Uri Buri, a spectacular fish restaurant in Acco run by a truly wonderful man (Uri Buri). This was the restaurant at which I once consumed what was without question the finest, most astonishing, original, and delectable meal I’ve ever eaten in Israel in all my twenty years there, and where I had the great pleasure of chatting at some length with Uri Buri—he looks like Santa Claus and mills around the restaurant talking to patrons—about how incredible his restaurant was. Buri also owns a hotel—and that was torched too.

Terrible, right? It’s actually worse. Uri Buri was clearly targeted because his restaurant and hotel are models of coexistence—they are renowned throughout the country, not only for their quality but for the fact that they are beautiful, inspiring examples of true, peaceful, genuine, quotidian coexistence. His staffs are made up of both Arabs and Jews, the patrons consist of both Arabs and Jews, and everyone gets along exactly as they would if they lived in a normal place where they weren’t being ordered to hate each other. Actually they get along better than that, as normal places don’t have the luster of miracle about them that kindness and friendship and good humor impart to a place where those things are forbidden. To walk into Uri Buri’s restaurant was to walk into an oasis of peace within a desert of hate, and that gave the air inside that place a unique, magical quality that doesn't exist in a normal city.

Everything that’s happening is sickening—but there is something so exceptionally and profoundly depressing about Uri Buri having his livelihoods destroyed explicitly because he is the very model of a true peacemaker, of a man who genuinely believes Arabs and Jews can live side by side and not only tolerate one another but love one another, and who has quietly and persistently walked that walk every day of his life. For that sin he must be destroyed.

I asked her if we could publish this letter, and she said yes.

We’ll have more to say about this in the coming days.

We return now to the final weekend (at last) of Energy Week.

I was just thinking this morning: "Why isn't there something on The CeeGee about Israel. "The CeeGee" is what the hipsters in downtown Seattle are calling the Cosmopolitan Globalist. At least I assume that to be the case. I rarely go downtown Seattle, and when I do, I steer clear of the hipsters.

A number of years ago I had the pleasure of working with a Tel Aviv based software firm. I worked with two of their (then) young software developers to implement their product for our company, which was based on the west coast of the United States. The one fellow was a Jewish Mystic, following the Kabballah, and carrying around magnetic stones. We'll call him Isaac. The other fellow came from a traditional Jewish home, his father was a Rabbi in Jerusalem, but he consider himself to be an Atheist. Let's call him Caleb.

One day, sitting in Burger King (that's right, Burger King), I sat and listened to Isaac and Caleb debate the Israel v. Palestine situation. Up until then, I'd just gone along with the traditional narrative on Israel: I was a conservative Christian, so I supported Israel. All Palestinians were evil terrorists. I was smart enough at that time to just listen, and ask questions. How could I possibly have any input on the conversation? Isaac wanted all hostilities to cease. He wanted Israelis and Palestinians to co-exist. Caleb said that was a pipe-dream. "You give them the West Bank, and they'll then ask for something else. And then something else. They have one goal: the destruction of Israel." It was a fascinating discussion.

After Caleb and Isaac returned to Israel, we continued to work together. At one point, Caleb stopped communicating with me. I got a bit angry, I mean, what are we paying these people for? After 3 or 4 unanswered emails, I sent something to he and the company owner, saying effectively "What the heck, man?!" Caleb responded "Sorry I haven't gotten back to you, but I will in a couple of days. I will explain later." When he did explain, I learned that Caleb was an officer in the IDF. He had been woken late one night because of some conflict, which saw him away from his job for about a week. He told me that while he was emailing me saying he'd get in touch with me soon, he was actually under fire by Palestinians. I asked him "Caleb, have you ever killed a Palestinian?" See, I'm smart, but I'm not that smart. Caleb's response shocked me: "I certainly hope so." He then explained further. "My wife takes 3 buses from home to her work in the morning. Then 3 buses from work to home in the evening. Busses explode regularly in Tel Aviv. How long until my wife is on one of them? We can't go to movie theaters. We can't go out to dinner. I hate Palestinians only because they hate me, and want me dead, just because I am Jewish." I would remember his words years later, standing in a coffee shop north of Jerusalem. I looked at the young lady who took my shekels and thought "She didn't ask for any of this. She just wants to live her life."

Fast forward then a few years, and I'm sitting in the home of an ethnic Palestinian in Amman. His family run out of Jerusalem when he was a baby, his father a Christian pastor in a small village in Jordan, this man now runs a charitable outreach organization in Amman. He had a different story to tell. "When Americans think of the Holy Land, they think only of Israel. But Jordan is the Holy Land, too." It was from him that I learned the difference between "Palestinian" and "Muslim", terms which I'd come to think of as synonymous in the context of Israel. Here was a man who was an Arab, a Palestinian by birth, and a devout Christian. He believed himself to be from the line of Ishmael. He reminded me of the passage in scripture in which Abraham asked God to bless the children of his union with Hagar. "We are those children. We are your brothers." Quite simply, his view was not any that I'd ever heard before. And it changed my perspective.

On that same trip I met a man in Bethlehem who had, as a teenager, saw his father killed by an IDF sniper. He became an atheist and a hater of Jews on that day. Years later he would become a Christian, and spend a goodly part of his life trying to bring harmony between Jews and Muslims in Israel. He told me "Palestinians only want a nation they can be part of, where they have a passport, and are free to move about the country as others do. We do not have that in Israel today." He told me that many, if not most Palestinians do not want a Palestinian state. They simply want a state. One in which they are free.

I don't really know what the answer is, which is to say that I do not know what the political answer is. I know what the right answer is. That answer is love. The answer is to listen to people tell their stories.