Read more about your editor and host, Claire Berlinski.

This publication was borne of the observation that genuinely global news coverage has all but disappeared from the Anglophone media. Thus the Cosmopolitan Globalist: a new publication that is neither national, nationalist, partisan, narrow-minded, nor provincial. The Cosmopolitan Globalist is, as the name suggests, cosmopolitan and worldly—and the center of our world is not Washington, D.C.

We are 68 writers and analysts around the world, shepherded into a single platform by Claire Berlinski in Paris and Vivek Kelkar in Mumbai. We’re united by our commitment to 18th-century Enlightenment ideals: rational inquiry, free speech, free trade, progress, tolerance, fraternity, constitutional governance, the rule of law, and the separation of state from church, temple, and mosque alike. We’re also united by our concern that these ideals may not survive the twenty-first century.

When societies are cut off from the rest of the world, they become intellectually weak and stagnant. The decline of foreign news coverage is closing the modern gates of Ijtihad.

We abhor the far-right, the far-left, and populism. But beyond favoring decency and common sense, we’re not otherwise passionately ideological, and we’re emphatically not partisan. Our aim is to offer educated, erudite, and credible reporting and analysis from the world around, treating issues of genuinely global import. We also host regular debates and podcasts, and we offer our readers a forum to discuss these issues with us and each other.

We strive to provide world-class coverage of consequential events even as we consider every issue from an informed local perspective. Our writers live in the countries from which they report. They understand local politics intimately.

We seek insight from academia and other experts. We value expertise. But we don’t worship it. Our style sheet bans the use of the phrases, “experts say,” and “science says.” We don’t chase breaking news. It breaks, we shrug. We strive, instead, to be more intelligent, reflective, astute, and accurate than any other publication.

To know what the rest of the world is thinking, you need to know where to look. That’s where we come in. Vivek and Claire have nearly a century’s worth of newsroom experience between them in every continent save Antarctica.

If you’re curious, sign up for our free newsletter. If you like it, you can pay to become a subscriber. Then your life gets much more interesting. Subscribing gives you access to our debate forums, Zoom calls, special events, book club, symposia, and podcasts, and you’ll also be able to comment on our articles. We have the most intelligent, thoughtful, creative, and civilized comment section on the Internet.

Plus, you’ll receive Global Eyes, our premium newsletter, access to our International Translation Superhighway, and a promise that the editor—Claire, that is—will personally answer any email you send her. You’ll also be supporting high quality, non-partisan journalism with a global perspective.

The Cosmopolitan Globalist: A FAQ

Who are the Cosmopolitan Globalists?

Claire’s friends, basically. From around the world. And Vivek’s, too. We’re mostly writers and journalists, but among us are academics, think tankers, Marine Corps combat veterans, diplomats, UN peacekeepers, refugees, former presidents, parliamentarians, bright students, industrialists, special envoys, particle physicists, geologists, waitresses, and lots of other things. If you’re our friend, you’re a Cosmopolitan Globalist.

Who is Claire?

Claire Berlinski is an American writer, journalist, policy analyst, and academic who for the past thirty years has lived and worked in the UK, the US, Switzerland, Thailand, Laos, Turkey, and France. She now lives in Paris amid a menagerie of adopted, elderly animals. She studied philosophy at the University of Washington, then Modern History at Balliol College of Oxford University, where she also received her D.Phil. in International Relations. She’s the author of many books, fiction and non-fiction, including two spy novels and a biography of Margaret Thatcher. She once taught Middle East politics at Santa Clara University; she’s been a fellow of the Manhattan Institute and a senior fellow of the American Foreign Policy Council, specializing in Turkey; and her journalism has been published in a long list of newspapers and magazines around the world. You can read more of her writing here.

How do Claire and Vivek know each other?

We met in 1995 in Bangkok, back when we both worked for the original print version of Asia Times. We founded the Cosmopolitan Globalist because the way global news is covered by the legacy media drives us nuts.

Where can I learn more about Claire and Vivek?

What’s wrong with the way the foreign news is covered?

The first problem is that it isn’t covered at all. Coverage of foreign news has all but disappeared since the end of the Cold War. In the US print media, there’s been an 80 percent drop in the column space devoted to foreign events.

Seriously?

No lie.

What happened?

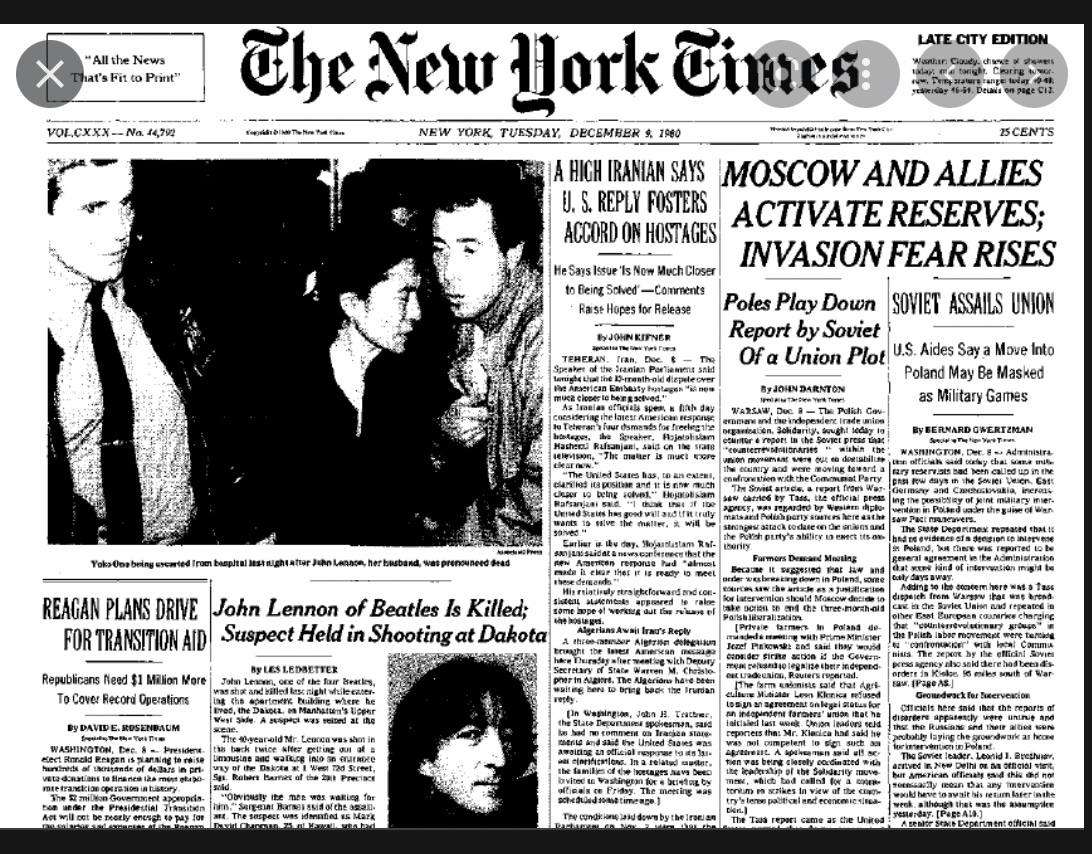

Newspapers, magazines, and networks have all reduced or eliminated their overseas correspondents. Between 1998 and 2012, eighteen American newspapers and two chains closed every last one of their foreign bureaus. Television networks slashed the time they devoted to foreign news. Foreign news made up about 40 percent of the broadcast news hole in 1980. Now, it’s less than four percent.

But why would newspapers stop publishing foreign news?

Because the business model that sustained journalism for nearly two centuries was destroyed by the Internet.

Since the end of the Cold War, newspaper after newspaper has failed. The ones that survived have been scooped up by vultures like Alden Global Capital, or by billionaires who think owning a venerable old newspaper could be fun, or useful for lobbying. They buy up the empty husks and completely restructure them. That’s why you hate the media.

Thousands of news organizations—print and broadcast—have vanished. Since 2005, more than 2,000 local print newspapers in the US have folded. The numbers are similar elsewhere. There are only half as many newspaper journalists working now as there were fifteen years ago. The surviving papers sharply cut foreign news coverage. Foreign news is one of the more expensive sections of the newspaper to produce, so it’s always the first to get the axe.

But how did technological change destroy the business model?

Foreign journalism used to be subsidized by the sports page, the gossip column, and the comics. Ads in the newspaper—especially classified ads—paid for written journalism, which supplied the bulk of original reporting to the English-language market.

But advertising migrated online, especially to Google Search. This completely changed the way people find and absorb the news. They no longer look at a newspaper—a single product, an inseparable bundle of politics, business, entertainment, and sports. They see individual stories, chosen by an algorithm. The shift of distribution and advertising revenues to Google and Facebook destroyed journalism. You’ve all seen what’s left. To boost online advertising revenue, publishers have been reduced to pushing endless culture war chum to generate clicks and hits. Opinion pieces have replaced reporting because opinions are cheap. (And you get what you pay for.)

Only a handful of professional journalists have survived this transition, often by turning themselves into minor media celebrities who write one after another variant on the same culture-war column. Pretty soon, though, even they’ll be gone, because we can now replace Glenn Greenwald and Mollie Hemingway with AI.

Once upon a time, during the Cold War, having a staff of foreign reporters was the mark of a local newspaper’s seriousness and prestige. But all of those jobs are gone. There are only about four newspapers left in all of the US who have foreign correspondents on their staff at all. The rest run wire-service stories, and that’s why they all sound exactly alike. You’d be amazed how much of the foreign news you read comes from Reuters. You’d also be amazed to learn that until very recently, Reuters was in partnership with TASS, the Russian news service.

You’re kidding, right?

Wish we were.

I’m shocked by that.

You should be. We recommend subscribing to the Cosmopolitan Globalist for your global news. Not one of us is in a partnership with TASS.

Another development is that editors and publishers now know exactly which stories readers look at and for how long. To justify their existence to their shareholders, they have to focus on the sections that get the eyeballs. That’s why the first thing you see if you look at most newspapers online is “Cooking,” not “World News.”

This is true everywhere, not just the US. But the US used to fund reporting around the world and drive the global news agenda. When the US dropped out of the picture, there just wasn’t enough left to pick up the slack.

You can read more about this here.

But isn’t it good that the US is no longer writing the whole world’s news? Doesn’t that mean local journalists, who know their countries much better, are doing the jobs Americans used to do?

Sometimes. But local journalists everywhere are facing the same pressures, so mostly, the news just goes unreported. If you want proof of this, try finding news from Africa—by far the most significant continent, demographically.

The US used to firehose money into foreign news reporting. Even minor newspapers funded fully-staffed foreign bureaus. Now, even the major newspapers tend to hire stringers and be tight with their budgets. The depth of coverage just isn’t the same. It can’t be.

So the foreign news that I sometimes see in my local paper comes from stringers?

Sometimes. But mostly, the little bit of foreign news you still occasionally see comes from AP and Reuters. Those two services have a completely disproportionate ability to shape the way people around the world see each other. Relying on the wires has eliminated all the diversity in foreign reporting, creating a global echo-chamber effect.

Newspapers and television and radio just stopped reporting news from overseas? How come I didn’t notice that?

Because it happened gradually, so you became habituated to it. But go back and look at a 1980 edition of any newspaper you read now. Look how much of it was devoted to foreign news, and how much emphasis they used to give to those stories. We chose the front pages below at random; these weren’t unusual dates, except in so far as John Lennon was assassinated:

Here’s today, for comparison:

But still, with the Internet, in principle we can find a lot of news from around the world, right? More than before?

Absolutely, yes. It’s astonishing. But it depends who you follow and how assiduously you seek it out. It’s true that you’re now able to follow the top ten Weibo accounts in, say, Chengdu from your desk in Milwaukee. You obviously couldn’t do that in 1980. But you probably won’t, because you won’t know that there’s a story in Chengdu that warrants your attention in the first place, and probably you won’t quite know how to use Weibo, or place the information you find there in context.

What’s the effect of never seeing any foreign news?

Epistemological disarray. We have no sense of what’s happening in the world at large or how we fit into it. The absence of a sense of the world changes the way readers see themselves and their place in the wider scheme of things. It’s not coincidental that isolationism and protectionism have risen as foreign reporting has declined.

There’s a clear correlation between the shuttering of newspapers and the decay of democratic and civic virtue. The clickbait economy encourages social polarization. It attenuates attention spans. It erodes literacy. It’s catastrophic for self-government. The effect is sufficiently subtle that people don’t necessarily see the connection. But if you look for it, you’ll see how many people have lost a robust sense that the rest of the world exists. That sense of the wider world has been replaced by morbid solipsism.

This is particularly acute in the United States, but the process is at work everywhere, not least because of the outsize cultural power of the US. It’s paradoxical that a famously open society like the United States’ has become so intellectually closed. The absence of news from abroad isn’t the only cause of this, but it’s certainly an important part of the story. America is no longer receiving an influx of new ideas from overseas, which makes American society, politics, and policy intellectually weak.

It’s often said that the Islamic world’s decline began when the gates of Ijtihad closed, around the time of the sack of Baghdad by Mongol hordes. When societies are cut off from the rest of the world, they become stagnant. The decline of the media is closing the modern gates of Ijtihad.

Q. But in principle, I could learn all about the rest of the world just by Googling it, right? There are tons of reports from NGOs and academics who study all these places. It’s not like there’s just no information out there.

A. You could. But generally, you won’t. Algorithmic sorting ensures you don’t see the clues that tell you you should be curious about something.

The social media revolution has given readers the power to customize their news feeds to an extraordinarily high level of precision. News producers are now wholly dependent on Google and Facebook to bring them their audiences. The big aggregators’ algorithms work by observing which stories interest their users and offering them more of the same—stories as similar as possible to the ones they’ve just read. So readers are never exposed to stories in which they’ve expressed no antecedent interest. The lack of foreign news coverage, like social polarization, becomes self-reinforcing. If you spend too much time wading through the mass amplification of dogma, idiocy, and degeneracy on Twitter and Facebook, you’ll give yourself brain damage.

That’s why we thought you might like a publication with an editor who figures out which foreign news stories are important—and which sources credible— then presents them to you in an attractive format. The Cosmopolitan Globalist saves you time and reduces your risk of brain damage.

People are beginning to realize that local journalism has disappeared and that this is a big problem for democracy. They don’t yet realize that the disappearance of foreign news is the biggest part of this problem.

How so, exactly?

The media’s role is to mediate between readers and places they can’t see or visit. Without foreign journalism, people no longer have a shared, reasonable view of the world. Without the influx of new ideas, you get the intellectual pathologies that now characterize our societies: hardened partisan identity, exaggerated partisan loathing that makes compromise and communication impossible; epistemic closure; the pathological narcissism of small differences; stereotyped views; rote, fixated, ideological, dead-eyed and intellectually empty discourse. The unmistakable sign of a mind that has ceased to work independently is the cliché—streams of them eructing straight from the speakers’ larynx without pause for the cerebellum. Reading the Cosmopolitan Globalist is proof against this tendency. It’s like an amulet.

Also, if you’re not regularly exposed to global news, you’ll have a much harder time making sense of your local environment. You’ll also have trouble figuring out what in your local environment is particular, rather than universal.

By which you mean?

Here’s one example. You may have noticed that recently we’ve been including articles about inflation in Peru and Sri Lanka. Why would anyone who doesn’t live in Peru or Sri Lanka care about that, you might think? But you’ll also note that in every country afflicted—that’s almost all of them, at this point—citizens are blaming their elected governments for rising prices. Elected governments in turn are blaming the pandemic and Putin. The global nature of the phenomenon suggests that for once, the elected politicians aren’t lying. This applies to many phenomena that people think are unusual, such as extreme political polarization and the rise of populism.

Conversely, if you read other countries’ newspapers, you’ll know that it isn’t true that every country in the world suffers from American levels of violent crime. (We mean “American” here in the larger sense: North and South America.) And mass school shootings are almost exclusively the provenance of the United States.

Do the Cosmopolitan Globalists have an ideology?

We do. We’re liberal, in the old-fashioned sense; we’re centrists; and we believe in democracy and the rule of law. But ours is a big tent. We have writers and readers who express the whole range of liberal, centrist, democratic spirit.

💸 But if the big media conglomerates can’t crack the problem of providing foreign news coverage and breaking even, why do you think you can?

Good question. We’re not sure that we can, to be honest. But here’s our theory.

First, as you point out, there’s actually no shortage of information about the world that can be found, if you know where to look. Even countries with no free media to speak of, like North Korea, still have a controlled media in which you can find significant clues about what’s happening there. And there’s a massive amount of newsworthy information on social media.

But it isn’t making its way into newspapers and news broadcasts. This is partly because of the way newsrooms are structured: They’re still organized on national lines; so the Washington Post is a US newspaper; the Kiev Independent is a Ukrainian one. But the editors of these publications—and there are very few of them left; they’ve mostly disappeared along with the journalists—tend not to understand foreign news very well.

We’re starting with the premise that our network of friends and contacts, which really does span the world, functions as our first-pass editor. Someone in Turkey, for example, will let Claire know if there’s a big story developing there. (She lived in Istanbul for a decade.) Vivek has the same feeling for Asia. Between us, Vivek and Claire have nearly a century’s worth of newsroom experience in every continent save Antarctica. And South America.

Second, there’s been another massive technological revolution, one that newsrooms so far haven’t figured out how to exploit. Google can now give us an instantaneous, free, perfectly comprehensible, and remarkably accurate translation of all the newspapers of the world, be they in Mandarin, Farsi, or Russian. Their translations are often of better quality than a professional one. Any American, even one who doesn’t know a single Chinese character, can now read any Chinese newspaper on the internet, from front page to last. And vice-versa.

Finally, if you think social media is a sewer and you don’t want to waste your time looking at it, we do it for you. (And you should think it’s a sewer and a waste of time, because mostly it is.) For an ordinary news consumer, it’s just too much of a slog to read several hundred foreign-language news sources and follow thousands of Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, and Telegram accounts every day. Finding genuinely important stories amid all the cat videos and Elon Musk memes is hugely time-consuming. We do it for you.

We scan about 200 newspapers in every major language, every day, then send you a selection of the most important and interesting items from Asia, Oceania, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. If we begin to suspect there’s an important story that hasn’t been written, we write it ourselves, if we can; or we shake down our friends and get them to write it.

No one else is doing this, as far as we know. The major news aggregation algorithms still serve only English-language results to their English-language news feeds. For reasons of habit and market demand, they never bother showing you the non-English sources. So you can be sure that if you read Global Eyes regularly, you’re really reading all the news that’s fit to print.

Q. I’m sold! But I’m still confused: What’s the difference between Global Eyes and the Cosmopolitan Globalist?

The Cosmopolitan Globalist is the name of this publication. Global Eyes is our premium world news roundup, which arrives regularly in our subscribers’ mailboxes. If you’d like to read it, you should subscribe: It’s a bonus for paid subscribers only.

What exactly do I get with Global Eyes?

You get the most important stories of the day from every major geographic region, and sometimes more, depending on the news. These days we’re also including regular updates from Ukraine and Russia, for obvious reasons. But unlike most newspapers, we’re not allowing the war in Ukraine to push all the other foreign stories off the front page. There will always be news from Asia, the Middle East, the Americas, and Africa, too.

Our guarantee: If you read Global Eyes regularly, you will be a reasonably well-informed person.

Do I get anything else?

You do! You also learn what the Cosmopolitan Globalists have been writing and reading elsewhere. Sometimes, you get short essays and blasts of opinion from the editors; sometimes, you get in-depth analysis: For example, a series introducing the basics of IR theory, or this extended essay on the work of geopolitical forecaster Peter Zeihan.

You also get a small, bracing dose of Russian and Chinese state propaganda at the end of Global Eyes. Look for 🦇The Daily Bat and 🥢 The CCP is disappointed with you, our insanely popular premium features. We allow the Russian and Chinese nomenklatura to speak to you directly so that you can be sure you’re understanding them correctly.

That sounds great! I can’t wait for the CCP to express its contempt for me. “Daily,” you say?

No, not daily. There’s a lot to do at CG—research, writing, editing, and trying to raise money—so some days, you won’t get a newsletter. But we strive for “daily.” Strictly speaking, it’s “most days.”

I guess that’s fair. What else do I get?

You get the Daily Animal! Or the daily architectural marvel, or the daily unknown literary masterwork, or another illustration of the world’s mystery, civility, and magnificence. Global Eyes can be depressing, seeing as the world these days is a grim catalogue of murder, mayhem, rape, starvation, and misery in every corner of the globe. But there’s a lot of good news that doesn’t get reported, too: It’s also a very beautiful world—a magnificent one—and we won’t let you forget that.

Thank God. Do I get anything else?

You do! You get Tecumseh Court’s Guide to Combat. Tecumseh Court regularly answers all the questions you’ve ever wanted to ask a US Marine Corps combat veteran about how to get ahead by making deadly war on your enemies.

Well, that sounds like a solid deal. I’m sold. But I’m still not sure I understand the difference between the newsletter and the website.

It’s easy. The website is where we keep an archive of essays, podcasts, interviews, and long-form journalism.

But why do you have a magazine in addition to a newsletter? That’s confusing.

Because when people write for us, they like to be able to say that they published their article in a proper magazine—one where it’s easy to find the article you’re looking for and the back issues are archived. Also, advertising is part of our revenue model, and you can’t advertise on a Substack newsletter. Finally, we’re going to be expanding, if we can find investors—and then we’ll add lots of new features and functions to the website. It will get bigger and much better with time.

I think I’ve got it. But why is it that when I press “SUBSCRIBE” over at the magazine, it takes me to this newsletter?

Because it’s the simplest way to handle subscriptions. Substack does a good job with credit card processing and billing. Adding a separate payment gate to the magazine seemed like a recipe for annoying our readers.

If you subscribe on Substack, you get automatic access to everything. You get all of our newsletters, you get Global Eyes, you get access to all the archives on Substack and in the magazine; you get the podcasts; you get the videocasts; you get invitations to all of our special events and Zoom calls; you get the Translation Superhighway, and you get to join our discussion forums and debates. The whole shebang, for one low price.

Q. Special events? Like what?

Well, recently our Cosmopolitan Globalist Book Club has been reading Bloodlands, by Timothy Snyder. And we’ve had debates, like our Great Energy Debate. But we’ve got a lot more coming up in the months ahead: stay tuned.

What’s the deal with the Translation Superhighway?

That’s one of our big ideas and our favorite things. Over in the magazine, we’re slowly adding a section where you can read all the major newspapers of the world through Google Translate. If you’d like to read the same newspapers we read when we choose items for Global Eyes, go over to the Translation Superhighway and pick your language. We tell you a bit about the newspaper your reading—its history, its biases, whether it’s apt to have been heavily censored—and we select half a dozen of the most interesting stories, every day. We’ve started with Russian and Arabic. We’re going to put up Hindi and Punjabi next. You can read lots more about the concept here.

Got it. What’s up with all the emojis in Global Eyes?

We’re going to use them at some point to create a searchable index, so that you can instantly pull up all the stories related to, say, inflation, or Singapore.

I want to support the Cosmopolitan Globalist, but I don’t want to subscribe.

Why not? Well, you can make a one-time donation on PayPal, if you like Or support Claire on Patreon. But the most helpful thing you could do if you don’t want to subscribe is share it widely:

And if you know someone who might like to advertise with us, or sponsor our podcasts, or invest in us, please make the appropriate introductions.

I’d like to reprint or syndicate an article.

We’d be very happy if you did! Send us an email and we’ll work something out.

Can I give a subscription to a friend?

Of course! This is a very popular thing to do.

Do you have CG swag?

Our readers said they weren’t interested in it, but if you are, let us know and we’ll revisit the idea.

I’d like to write for the Cosmopolitan Globalist. What should I do?

Send us a pitch! We’re interested in the whole world. We’d especially like to hear from you if you’re in Southeast Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, or Latin America. The only thing we’re not interested in is “My Big Opus on Transexual Swimmers” or some other well-worn trope of the Culture War. If we need those, we’ll generate them with AI.

I think what you’re doing is terrific and I’d like to invest in CG.

Drop us a note! We’ll show you our pitch deck and tell you what we’d do with your money.

Why did you call it The Cosmopolitan Globalist?

You try finding a domain name suitable for an international journal of global affairs that isn’t taken already.

But isn’t that a Stalinist antisemitic insult?

Yes. But we don’t care what Stalinist antisemites call us.

Claire, I know you don’t want to write about the culture war, but I love it when you write about #MeToo and guns.

Yeah, okay. Every so often. But it’s like cheesecake. In small portions it can be part of a balanced diet. But not every day, come on.

Why do you sometimes put people’s names in bold?

It means that person is one of us. He or she has written for us, subscribes to us, or is in some way part of the club.

How many of you are there?

No idea! About fifty of our friends have written for us so far, and we have high hopes for the rest.

Say, who are your readers? Where are they from?

According to our stats, about half of them are in the US. Another quarter are from Europe—we get some from every country, but we’re especially big in Lithuania. We don’t know why. The remainder are from everywhere: India, Russia, Israel, Nigeria …

Our readers are great. They’re well-informed, curious, literate, and funny. We always tell our writers that they don’t have to write down: Our readers can handle complexity. You can even read the comments on our articles without wanting to slink into a hole and die. We don’t have to edit or censor them because our readers are unfailingly polite. How many publications can make that claim?

Hey, maybe I should advertise my Bespoke Widgets to your discerning readership on the Cosmopolitan Globalist?

Of course you should! Send us an email. You could sponsor a podcast, too.

I subscribed, but I’m not getting the newsletter.

Try this, first, and if that doesn’t help, send us a note and we’ll fix it, pronto.

I have another technical question about my subscription or billing.

Here are the solutions to the most common problems. If they don’t work, send us a note and we’ll fix it, pronto.

Q. I have another question that you didn’t answer.

A. Send us an email: We’ll add the answer to this FAQ.

I’d like you to explain all of this in a video.

Try this:

I’m sold! How do I subscribe?

Right this way! ➘➘➘➘➘➘➘➘➘➘➘➘➘➘➘➘