Social Media and the New Man, Part II

Faithful readers,

It’s taken me forever to put out the next installment of this newsletter because I’ve had too much to say. I can’t quite figure out how to make a chapter flow coherently over a series of newsletters. Perfectionism will be the death of this project, though, so I’m going to hit “send” on this today, whether or not it’s the best I can do. I know it’s too long. But just save it and read it in parts over the next few days, okay?

And please don’t forget the immortal wisdom of Dr. Johnson: No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money!

Here’s Part 1 of Social Media and the New Man.

Growingly, I see the Internet, and particularly social media, as the primary cause of our breakdown into mutually hostile camps, each of whom views the other as complete lunatics. I don’t think we’ve fully appreciated how revolutionary this technological change is and the degree to which it has introduced into our lives something the human race has never experienced, and for which it hasn’t developed institutions or long-standing mores with which to cope.

With the invention of social media, we had a revolution. People of a conservative temperament hate revolutions for a reason. If you had asked me, when Facebook debuted, “Does the world need a revolution? Because that’s what this product entails,” I would have said, “Strangle it in the cradle.”

None of us realized how much social media would change our relationship to the world, each other, and the truth. None of us had the sense to say, “Yes, this could be an enormously useful product, but it should be slowly introduced to humanity over a period of 200 years, not suddenly unleashed on an innocent public that has no idea how to cope with it. It will take us two centuries to develop all the laws, wisdom, and institutions we need to make sure this is a boon to us, not our downfall.”

But history doesn’t work that way, alas. We had a revolution—we’re still having one—and it has changed everything. Old rules no longer apply. We’re living in a new epistemic and social world, one for which we’re simply unprepared.

Are we on the verge of civil war?

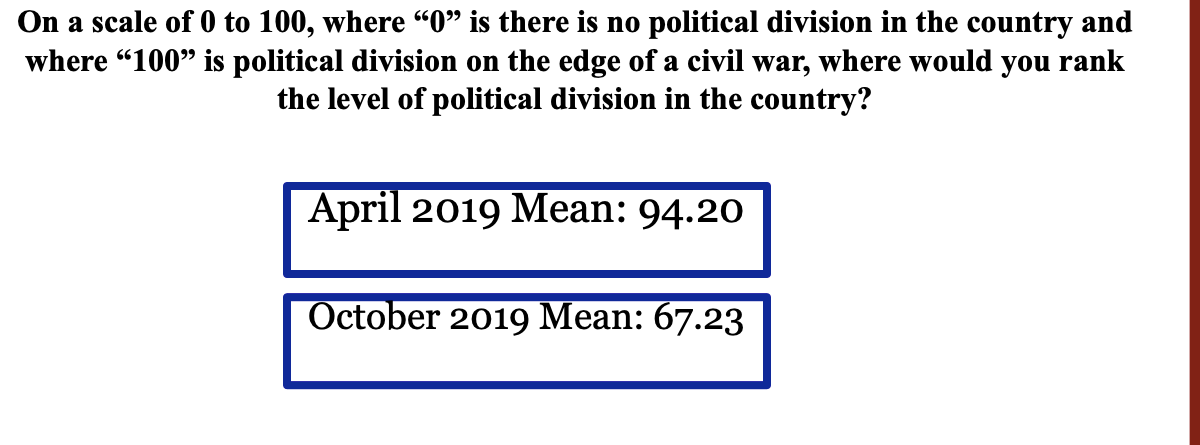

Speaking of polarization, the Georgetown Institute of Politics and Public Service recently released a poll. They asked 1,000 Americans to rate the acuity of our political divisions on a scale of 0-100, where 0 indicates “no social tension at all,” and 100 indicates “on the verge of civil war.”

The mean response was 67.2.

Countless news outlets reported this thus:

How close is America toward Civil War? About two-thirds of the way, Americans say.

Voters believe US two-thirds of the way to 'edge of a civil war': poll

Poll: Majority Of Americans Fear We Are On The Verge Of Civil War

Take some time with it. Compare what it actually says to what the headlines say.

What I printed above was only a small sample of the headlines I saw. I must have seen about fifty—all equally wrong, and not just wrong, but shockingly innumerate in a way that makes me wonder how we’re sustaining an advanced industrial economy. Why aren’t our airplanes just falling out of our skies?

These headlines appeared in outlets spanning both partisan and class divides. The headlines were wrong in both the low-rent Internet tabloids and in the coastal-elite media: No one read this poll carefully.

Blame it on the pollsters, in the first instance. The more attention this kind of research gets, the easier it is for them to get the next round of funding. That’s perhaps why they sent out a press release with a sensationalist headline that failed to represent what people told them.

So, the press release:

NEW POLL: VOTERS FIND POLITICAL DIVISIONS SO BAD, BELIEVE U.S. IS TWO-THIRDS OF THE WAY TO “EDGE OF A CIVIL WAR”

That’s wrong. Completely.

Then we can blame the journalists. Perhaps they didn’t read the press release, no less the poll itself. Had they read through to the third paragraph of the press release, they would have seen this:

These observations contribute to the Civility Poll’s additional finding that the average voter believes the U.S. is two-thirds of the way to the edge of a civil war. On a 0-100 scale with 100 being “edge of a civil war,” the mean response is 67.23.

Are you not immediately seeing the problem? I’ll walk you through it.

There’s a scale from 1-100, with 0 representing “no social tension at all,” and 100 representing “the edge of civil war.” When asked where we were, the mean response was 67.23.

That’s the mean response, not the median or mode. In other words, they added up all the responses and divided them by the number of respondents. What value would make this number meaningful, and what value is not offered? Class? Anyone?

That’s tight. Range. If I have a hundred dogs, and I want to know their mean weight, I can add up all the dogs’ weights and divide the number by 100. Suppose I find that the mean dog is ten pounds overweight.

Does that tell you, “MOST OF THESE DOGS ARE 10 POUNDS OVERWEIGHT?”

No, it doesn’t. We don’t know the range. It’s possible that every single dog was ten pounds overweight. Then it would be fair to say, “Most dogs are ten pounds overweight.” But it’s every bit as possible that no dog was ten pound overweights. Say a lot of them were skinny. But the majority were obese.

It’s possible that every single respondent replied, “67.23.” It’s equally possible that half replied “34,” and the other half replied, “100.” (I’m rounding.) If it was the former, not a single American polled believed we were on the verge of civil war. If it was the latter, half of Americans polled believed we were nowhere near civil war, and half believed we were on the verge of civil war.

That the mean value was 67.23 does not mean that “a majority” or “two-thirds” of Americans believe we’re on the verge of civil war. It doesn’t tell us anything at all unless we know the range.

If 100 percent of Americans had replied “67.23,” it would not entail that two-thirds of Americans believe we’re on the verge of civil war. It would suggest that all Americans think we’re two-thirds of of the way toward being on the verge of a civil war.

And it is a meaningless question in the first place. What does “two-thirds of the way toward a civil war” mean? How did respondents understand the question? Did they think, as I would, that “0” would be just as dystopian a number as “100,” given that a nation with “no political divisions” would comprise the null set and otherwise be entirely inhuman? How are we defining “civil war?”

The whole poll is a gumbo of meaninglessness. It leaves us with some data suggesting, maybe, that some Americans are feeling a bit of agita.

Here’s the stupidest part. No one noticed this:

So a more accurate headline by far would be, “Belief that America is close to civil war falls dramatically.”

Or perhaps, “Who the hell knows what this poll means?”

You’re the center of the world

So why did you see all of those obviously sensationalistic and mathematically illiterate headlines?

Because you click on them.

Your desire to be outraged and sensationalized creates a market for the outrageous and sensational.

Although we’re not on the verge of civil war, we are polarized, politically, and we’re profoundly ignorant about what’s really happening beyond our borders. These are problems. They make it impossible for us to govern ourselves, and they make for disastrous foreign policy.

Why?

Simply put, cable, the Internet and other technological revolutions in news gathering have resulted in too much consumer choice, which gives consumers who are in no position to determine what’s newsworthy all the power to decide what they think is important. That they’re in no position to determine what’s newsworthy is not because they’re stupid. It’s because, by definition, they are news consumers. They wouldn’t be trying to get the news if they already knew it, would they?

News consumers now customize the information they receive to an extraordinarily high level of precision and ignore everything else. Because stories are no longer bundled together in a single physical item—nightly news, the newspaper—the reader no longer has to slog through, or at least cast his eyes over, stories about high-level meetings on arms control negotiations to get to the sports page. We choose each item with a mouse-click—goodbye, list of boring economic indicators. Hello, American Civil War!

Advertisers carefully measure the amount of time you spend looking at any given page on the Internet. They’re interested in only one thing, and it’s not, “Does it leave you better informed?” No, they couldn’t care less if you read it backward instead of forward. The only thing they care about is this: “Does it convince you to linger on the page long enough to click on the ad and then buy the product?”

Eyeball time on the page is linked to your propensity to click through the ad. Clock how long your eyeballs rest upon any given story. The advertisers truly don’t care if you’re pleased or enraged by it. If something gets your attention, from their point of view, that’s good. They’ll show you more, in particular, of the thing that most enrages you. By reading that story, you’re telling advertisers how to get your attention, and it doesn’t matter if the attention is good or bad. It’s good for them.

Humans prioritize news that enrages them. We seem to be designed to do this. The reasons for this are probably self-evident.

The New Yorker ran a good piece about all of this recently. It may even seem to you like an apology, of sorts:

Chartbeat, a “content intelligence” company founded in 2009, launched a feature called Newsbeat in 2011. Chartbeat offers real-time Web analytics, displaying a constantly updated report on Web traffic that tells editors what stories people are reading and what stories they’re skipping. The Post winnowed out reporters based on their Chartbeat numbers. At the offices of Gawker, the Chartbeat dashboard was displayed on a giant screen.

Think of your attention the way you’d think of cold, hard cash. Advertisers now know everything about you. They know exactly which stories are alluring to you and where you are when you click on them. They know your history of online purchases and your zip code. They know all the demographic data that you willingly shed into the Internet, every day. They spend a lot of time analyzing it. They can judge with considerable confidence what kind of story is going to get you to do what they want.

They want you to buy what the advertisers are selling. They don’t care about the political consequences of the stories they’re using to sell their products.

So they want you to linger on that page until you notice the ad—the one that informs you about a sale on power tools at the local mall; or the latest white-cropped skinny jeans; or a report, at the low, low price of $1,459, about the online advertising market.

This is called “behavioral advertising.” It leads to a higher “conversion rate,” as they call it. It’s better than billboards, better than radio, better than the Goodyear blimp. There’s nothing like it.

Advertising is no longer based on a hunch. It’s not even based on polling data. It’s based on you. You’re seeing ads that reflect the amount of time you’ve spent on every page you look at on the Internet.

They know the route you took to get at those pages. Did you get there by means of Drudge? By MSNBC? That’s information you willingly provide to big data whenever you buy something online.

Do you get outraged when you read about Trump? Or the “coup against Trump?” Well, stories about Trump being Trump and the “coup against Trump” are what you’re going to see, every time you look at the news, until you’ve spent your last disposable dollar and you’re lathered into a violent frenzy.

Consider this. If you buy those skinny jeans, that information is going to be used to sell you health insurance.

How? Well, if you can fit in those jeans, you’re not overweight. (Data point 1.) You’ve already told Facebook that you’re 23. (Data point 2.) Tinder knows that you’re actually attractive, as opposed to just thinking you are. (Data point 3.)

You shed data like dandruff. You don’t have a long commute. You’re less likely to die in a car accident. You’ve never searched for, “I’ve just been diagnosed with glioblastoma.” (Good sign.) Are you shopping for “x-treme paragliding gear?” Your life expectancy just went down.

Remember, all of this is information someone actually has, and you willingly agreed to share it. Yes, you did. You just didn’t read that long contract very carefully.

So now you can be bundled with other healthy young people like you into a low-risk, low-cost health insurance pool. And you’ll love it.

Skeptical? Fine, but note it down. When they debut the product, you can say, “I guess she was right.”

Chomsky and Herman were partly right

Reporters and editors used to drive the news agenda. But for the most part the media was, contra Chomsky, a liberal and dutiful class of people who strove earnestly to inform you about things they believed were important—and who were not nearly as stupid as Chomsky believes they were. Yes, they were selling a product. No, they were not just selling a product.

Journalists don’t drive the agenda that way anymore. You do. You click, we give you more of what you clicked on.

Occasionally, “news” organizations break even by chasing #Trump or the #crazythingswokepeopledo. Then a high-minded editor might have the very rare privilege of paying a real reporter to do a real news story—usually supplemented by a philanthropist who gives the reporter a grant.

But there’s not much left of the news gathering and reporting apparatus that existed when we were kids in America. The old guard, which liked to think it had a higher calling to report “the news,” has mostly died, or been forced out, or overruled. What’s being sold to you now as “the news” is, for the most part, “politics-flavored entertainment.” Every story is chosen on the basis of how likely it is to make you click on it.

A few years ago, the predictive algorithms became accurate enough to say, to a high degree of specificity, not only what people would click on, but what kind of product they would buy when they clicked on those stories.

The algorithms match the kinds of stories the customer likes, the kind of mood the customer likes to be in before he or she spends money, the customer’s tastes in consumer goods, his income, his purchasing patterns, and even the desires he isn’t consciously aware he feels, using a surveillance apparatus more totalitarian and dystopian than anyone ever had the imagination to foresee.

The outrage du jour

I belong to a friendly e-mail list comprised of people who like to share thoughts on strategy and national security. Because everyone on the list is human, though, half as often as not the topic of discussion is the outrage du jour. There is always an outrage.

A few weeks ago, the outrage was the local hero in Iowa who raised a million dollars for a children’s hospital. Do you remember that one?

What started as a quest for a little extra beer money has evolved into a million-dollar gift to children in need.

Carson King went viral last week with a homemade sign asking viewers of ESPN’s College GameDay to donate to his Venmo account so he could afford to stock up on beer. ….

By the end of the day, he’d accumulated more than $1,000—and quickly realized that the fast-growing cash would be put to much better use at the University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital, as opposed to his wallet.

And what does the media do? They scour our hero’s Twitter feed and find—miserabile visu!—that at the age of 16, he Tweeted something racist. Then they publish his adolescent Tweets, prompting ritual expressions of shame and apologies all around. But too late! Anheuser Busch drops its matching donation. Rough luck for the kids with cancer. The public is outraged, and naturally, the outraged public scours the reporter’s Twitter feed only to find that he too had said something racist as a teenager. The newspaper bravely fires their reporter.

This story got my friends hopping mad. “The editor who signed off on the piece should also be fired. Everyone who was involved should be fired. This isn’t journalism,” one wrote.

Not to be outdone, another friend replied, “Whenever there is a major disaster like the Challenger explosion or 9/11, it is common for there to be a blue ribbon commission to look into how it happened and what can be done to prevent similar things in the future. We need such a commission to figure out what happened to journalism.”

Save the commission. I can explain.

Here’s what happened to journalism

It turns out that everything you hate about the media is your fault.

Let’s begin with foreign news coverage. I moved to Turkey in 2005. For a few years, I was able to support myself as a freelance writer. But after the financial crisis, almost every news outlet to which I had sold news articles about Turkey went under. Those that survived, and they were few, had a single message for me. “We’d be interested in publishing something by you, but we’re not interested in Turkey. Could you pitch something else?”

That year, I published an article in City Journal titled Less than Splendid Isolation.

The explanation for the decline of professional journalism is by now so familiar that it hardly needs rehearsing. (Internet, recession.) Harder to explain is the decline in the ratio of foreign to domestic news. The phenomenon is particularly striking if you live, as I do, in a country that has largely dropped off the media’s radar screen. It’s still more obvious if you’re a journalist: no one wants stories from Turkey these days.

Days before, the spokesman for the Turkish Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee had addressed a group of journalists in Istanbul. His topic—“Is Turkey drifting away from the West?”—struck me then, and still seems to me, important. But no one from a major US daily or news station attended—even though journalists from Britain, Belgium, Spain, and Greece did. “The Americans never come,” the organizer said.

I could not give this story away to Americans. “Sorry, Claire,” wrote the editor of one news magazine, to whom I pitched the story. “We’re not interested in Turkey stuff.”

By 2012, by my rough count, about half of the Western journalists based in Istanbul had taken the bait and gone to work for al-Jazeera. They were the only ones hiring. Everyone else was shutting down, or “not interested in Turkey.” This was especially remarkable because the Syrian civil war was obviously becoming one of the most significant stories of the century, and just as obviously, Turkey was critical to this story.

In-depth international news coverage was vanishing from America’s mainstream news. What little made it into the news wasn’t sufficient to permit readers to grasp what was happening overseas or to form a wise opinion about it. Worse, a lot of it was just wrong. Factually wrong. The phenomenon was non-partisan. It was as true at The New York Times as it was at Fox. The way The New York Times was wrong was usually much more subtle, but it doesn’t matter: wrong is wrong.

But this was odd. It was counter-intuitive. This was the era of the Internet, mobile phones, social media, citizen journalism. In theory, it was easier—far easier—to learn about the rest of the world. Why then, in practice, was news about the rest of the world disappearing?

Television, foreign news, and nuclear war

One might argue, and some have, that the phenomenon requiring an explanation is not Americans’ loss of interest in the news from abroad, but the brief period—during the Cold War—during which Americans did exhibit this interest. It is probably not a coincidence that this was the television era, and not just the television era, but the era of the broadcast cartel.

In 1963, NBC and CBS doubled the length of their nightly news programs from 15 minutes to 30. The networks were unsure whether there was an audience for a longer program. To prove their value, they began bulking up foreign coverage. Having a network of foreign correspondents, news editors believed, was proof of credibility, a sign that the news organization spared no expense to be on the scene wherever important events were taking place.

By the 1970s, the development of satellite technology made same-day coverage possible, and television had lost the Vietnam war.

As Garrick Utley wrote in 1997,

The mass public in the United States has never shown much sustained interest in what is happening abroad. Throughout the nation’s history, the American sense of self-containment has rarely been challenged, and then only by direct threats to U.S. interests. The Barbary pirates’ “terrorism,” the War of 1812, and the sinking of the Maine were international punctuation marks of the nineteenth century. In this century, too, Americans’ interest in foreign affairs has generally been limited to war and the threat of war. The longest of these conflicts, the Cold War, coincided with the growth of television, from the late 1940s to the late 1980s.

During this period, however, for the first and last time, Americans took a keen interest in news overseas.

Utley believes this was because “nuclear weapons were aimed at American communities.”

Could that be?

No. This hypothesis doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. If Americans paid attention to news from overseas chiefly because nuclear weapons were aimed at their communities, they would be keenly interested in news from abroad.

Our loss of interest in the prospect of nuclear war is one of the great mysteries of the modern era. Regularly, I see such constructions as this in the media: “Back during the Cold War, when we were threatened with the prospect of nuclear annihilation … ” As if, truly, this prospect had come to an end.

Russia regularly threatens to vaporize American cities. The number of countries capable of annihilating the United States has grown. The major powers have been upgrading their arsenals. They have been testing, producing and deploying new weapons with an uncertain effect on traditional deterrence doctrines. Arms control efforts have serially failed: a qualitative global nuclear arms race is now underway; the world’s nine declared nuclear states are spending hundreds of billions of dollars to improve their arsenals. Tensions between nuclear-armed states are sharply on the rise. India, Pakistan and North Korea are enlarging their nuclear arsenals as fast as they can. Key treaties have been broken or are under threat. The US has withdrawn from the INF and Open Skies Treaty. START is headed for a similar fate.

The Trump Administration has begun rolling out low-yield nuclear weapons and writing first-use doctrines for them. This idea had been entertained during the Reagan era; the Administration conducted extremely elaborate war games to see what would happen:

The result was a catastrophe that made all the wars of the past five hundred years pale in comparison. A half-billion human beings were killed in the initial exchanges and at least that many more would have died from radiation and starvation. NATO was gone. So was a good part of Europe, the United States and the Soviet Union. Major parts of the Northern Hemisphere would be uninhabitable for decades.”

This is why a shaken Reagan emerged to say, “A nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought.” He reaffirmed this, with Gorbachev, on signing the INF treaty in 1987.

Both the United States and Russia retain launch-under-attack postures that increase the risk of miscalculation. The international system has been profoundly destabilized.

Serious voices in Germany are calling for the acquisition of the Bomb. So are serious voices in Australia. Likewise South Korea and Japan.

Donald Trump has absolute authority to launch nuclear weapons, without anyone else’s consent. He has reportedly asked why, if we have nuclear weapons, we can’t use them. His supporters aver that this is fake news. It may be. But that’s not the point. The point is that we can all imagine him saying such a thing. His temperament is such that this seems, very much, like something he would say.

No, we are now more at risk of nuclear war than ever before in the history of the human race.

So why is there still so little coverage of events overseas?

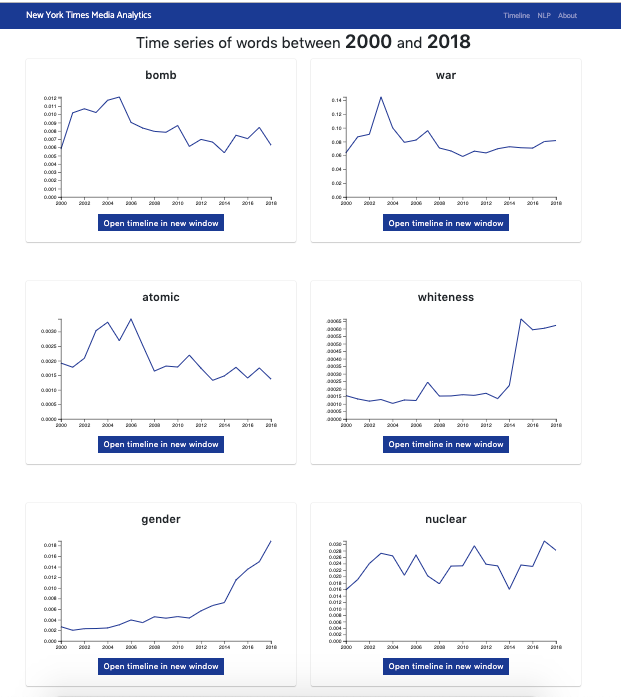

Certainly, Americans no longer fear nuclear war as they once did. An analysis of word-use frequency in The New York Times certainly suggests we have larger preoccupations:

(Note that the values on the y axis are not held consistent.)

Perhaps it’s simply a matter of acculturation: We’ve managed to go this long without a nuclear exchange, people think, so it can’t happen.

Or perhaps it’s because we no longer receive news from abroad.

Perhaps Garrick Utley has it exactly backward.

Cable, the VCR, and Satellite

In 1989, ABC broadcast 3,733 minutes of foreign news into American households. By 1996, the number had declined to 1,838 minutes.

During the Cold War, every major American newspaper and television station covered foreign news, particularly from the Soviet Union and Europe. American television networks set the standard for global news coverage and drove the global news agenda. All the major networks had bureaus across the globe, staffed by correspondents who had long been on the ground. Whether they were in Berlin, Cairo, Istanbul, or Moscow, they knew their region, they knew the people, they spoke the local languages, and knew the history of the stories they covered.

Even small local papers had bureaus overseas. They hired foreign correspondents, paid them a living wage, and sent them—and their families—to foreign countries with generous expense accounts and housing allowances and a budget for interpreters and fixers. Their reports ended up on the papers’ front pages, or, in the case of television news, at the top of the hour.

What happened between then and now?

The big three broadcasters were a cartel. In 1980, more than 90 percent of Americans watched ABC, NBC, or CBS during prime time. With essentially captive audiences, they could afford to compete against each other to do expensive things, like covering the news abroad.

By 2005, the number had fallen to 32 percent.

The explanation for their demise is largely technological. The rise of new cable networks and the widespread penetration of the remote control device offered viewers the chance to see something else. New broadcast networks, such as Fox, Telemundo, Univision, and Azteca, cut into the big three share, but overall, the audiences were lost to cable, the VCR, and satellite.

Consumer and advertiser spending on mass media has remained relatively constant. But these resources are now spread over 90 channels instead of three. Voilà: there are no resources left for foreign news coverage.

Foreign news coverage is the most obvious example of “how competition made television much more entertaining but much less good at conveying the news.” But it’s the same across the spectrum: The resources for reporting on the United States itself are similarly spread thin.

It’s common to say that people have lost confidence in the media because the media isn’t trustworthy. It’s much more accurate to say that the media has become untrustworthy because doing good reporting is resource-intensive and no one wants to read, or watch, good reporting. “Watching it” is paying for it. Given the choice between carefully reported, professional, fact-checked news programs and 120 much more amusing shows, people decide not to suffer through “the news.” “The news” now has to compete with “the best television shows ever made, streaming in on Netflix,” and everyone seems to like the show about the woman with dragons more.

Don’t blame Fox, by the way. I know everyone thinks Fox has stolen their parents and turned them into drooling zombies, but no one actually watches Fox, either.

As for the decline of print media, this one’s quite obvious: It’s the Internet.

What that blue-ribbon commission would tell you

Cable, the Internet and other technological revolutions in news gathering have resulted, to put it simply, in giving consumers who are in no position to determine what’s newsworthy too much power to decide what they think is important.

News consumers may now customize the news they receive to an extraordinarily high level of precision and ignore everything else. Because stories are no longer bundled together in a single physical item—the newspaper—the reader no longer has to slog through, or at least cast his eyes over, stories about high-level meetings on nuclear disarmament in order to get to the sports page. We choose each item with a mouse-click—bye-bye, Open Skies, hello American civil war.

It’s damn good for CBS

It’s one outrage after another, isn’t it? What the media did to those Covington boys, right? Not just obscene, but painfully stupid. For days, journalists of every political disposition could not stop banging on about those Covington kids in MAGA hats who harassed a Native American veteran at the Lincoln Memorial. The media managed somehow to turn that story into the week’s most important news and a sign of our terrifying times even though it was not true; an equal number of column inches were then devoted to denouncing the journalists who denounced the teenagers.

The media has persuaded a whole generation of kids that we will all, literally, boil to death in eleven years, even as it systematically ignores the growing threat of nuclear annihilation.

And let’s not forget: the media put Trump in the Oval Office. Chasing ratings, it gave him two billions dollars worth of free coverage. “It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” said Les Moonves:

Man, who would have expected the ride we're all having right now? ... The money's rolling in and this is fun.

I’ve never seen anything like this, and this going to be a very good year for us. Sorry. It’s a terrible thing to say. But, bring it on, Donald. Keep going.

The Centre d’analyse, de prévision et de stratégie and the Institut de recherche stratégique de l’École militaire co-wrote a report describing the scope of the problem. They specifically use the phrase “epistemological crisis.” That there is such a crisis is well-known among people who work in the media and the military, but I don’t believe it has truly filtered down to most mass media consumers, who still believe they’re savvy enough to distinguish real from fake reports.

Most people now get their news from social media, not from established newspapers. But most people don’t realize that established newspapers rely on Twitter for a very significant proportion of their foreign news coverage. (Have you noticed how often the dateline, in newspapers like the Times and the Post, is not the city or country in question?)

I don’t think people truly realize how weird the situation is—yet. I think that as of now, people still think they’re getting a “pretty good sense” of what’s true and what’s false from what they read on the Internet. Trump’s supporters read Breitbart and Drudge, watch Fox, and follow right-wing accounts (of which a sizable proportion are Russian). The rest of America reads the Times and the Post, watches CNN, and follows mainstream or left-wing Twitter accounts. (Much of the far-left on the Internet is also Russian: They’ve just dusted off the COMINTERN files.)

People express disgust and distaste for “the media,” and claim that the opposite side is fake. They don’t yet fully realize how fake it is and how much of what they think of as their own side is fake.

In the coming few years, this will become clearer to people, especially when people start seeing a lot of deep fakes. Then they’ll really get it that the line between true and false has been hopelessly blurred.

I don’t think people will like that feeling. I certainly don’t.

How to get better journalism

Here’s how to make journalists stop doing things like “publishing a vaguely offensive thing that a local hero said on Twitter when he was sixteen.” It’s so simple you wouldn’t believe it.

Never, ever click on stories about that kind of thing.

Think of your attention the way you’d think of cold, hard cash.

They’re measuring the amount of time you spend looking at stories like that. The amount of time your eyeballs spend on the article or articles about the article is all they care about. By “they” I mean advertisers, and it doesn’t matter if you’re pleased or enraged. If something gets your attention, they’ll show you more of it. They’ll show you more, in particular, of the thing that most enrages you. By reading that story—and—this is key—stories about that story, you’re telling advertisers how to get your attention, and it doesn’t matter if the attention is good or bad. It’s good for them.

This truly isn’t a conspiracy theory of any kind, as fantastic as it sounds.

You saw that “America on the verge of Civil War” headline, whether you’re on the right or the left.

You saw it because you wanted to see it. Your fantasy created it.

Your outrage has been successfully manufactured.