The Media Revolution and the New Man

Manufactured outrage and the breakdown of liberal democracy

So you say you hate the media?

I believe I know why.

The economic and technological transformation of the mass media is a key aspect of the story of the decline of liberal democracy.

Note: It is not irreversible. Nothing is written.

But do not assume it will all work out well.

Some of you may know parts of this story; others, different parts. I’m going to draw them together here in a way that, I hope, provides a useful overview.

The Liberal View

In the liberal view, freedom of expression is to be treasured for two reasons. The first is inherent: It is an aspect of freedom, and freedom is inherently—self-evidently—good.

The second is utilitarian. Freedom of expression, in the liberal view, gives rise to a marketplace of ideas.

The metaphor of a market comes to us from Milton, who in Areopagitica deplored Parliament’s 1643 Ordinance for the Regulating of Printing.

Though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously, by licensing and prohibiting, to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter?

Ideas and Markets

The analogy to a marketplace is interesting, suggestive, and flawed. There is in fact no market in truth, in the classical sense, because there is no price mechanism. Milton acknowledged as much:

Truth and understanding are not such wares as to be monopolized and traded in by tickets and statutes and standards. We must not think to make a staple commodity of all the knowledge in the land, to mark and license it like our broadcloth and our woolpacks.

Knowledge and truth, in Milton’s view, are similar to goods one might trade in a marketplace, in that competition gives rise to better products. Yet they’re also different: They are not ordinary commodities.

Liberals have long believed that if ideas are allowed to compete freely, the truth will emerge. The public will weigh and measure ideas, opinions, proposals, policies and Weltanschauungs. The better ideas will naturally win. They will become laws and policies.

The Fourth Estate

The term “Fourth Estate” reflects the liberal precept that the media, in a healthy polity, plays a critical role—one as weighty as the executive, the legislature, and the judiciary. The term is a neologism. In medieval Europe, the First Estate was the clergy; the Second, the nobility, and the Third the peasantry.1

In the liberal view, the media serve as guardians of the public interest. A free press affords the public the opportunity to supervise and scrutinize those who hold power. It is an essential component of the system of checks and balances designed to proof democracy against despotism.

Jefferson, particularly, averred with a faith and urgency that no one alive now feels that truth would emerge from freedom of the press:

… The art of printing secures us against the retrogradation of reason and information.

… To preserve the freedom of the human mind ... and freedom of the press, every spirit should be ready to devote itself to martyrdom; for as long as we may think as we will and speak as we think, the condition of man will proceed in improvement.

Where the press is free, and every man able to read, all is safe.

Manufacturing Consent

In 1988, Chomsky and Herman published Manufacturing Consent. The title comes from the phrase “the manufacture of consent,” used by Walter Lippman in 1922 in the book Public Opinion. The consent in concern is the consent of the governed.

The ideas are not original. (Chomsky says Herman wrote most of it. I believe him.) It’s a standard neo-Marxist analysis. But Chomsky’s fame propelled the book to enormous prominence. It’s now the best-known objection to the liberal view of the media. Or the second-best, perhaps; I suppose the best-known objection is Donald Trump’s.

Chomsky are Herman argued that the marketplace of ideas is, indeed, a market. This is not a metaphor. Their model was “simply a free-market analysis of the mainstream media,” they claimed, and the results were “largely the outcome of the working of market forces.” But just as there was no reason to think a market for broadcloth and woolpacks would give rise to truth, they said, there is no reason to think truth would emerge from a marketplace of ideas.

The American mass media, they allowed, was not censored in the Soviet style. But they believed it functioned even more effectively as a comprehensive system of propaganda, for contrary to received wisdom, the media was neither liberal nor dedicated to the public interest. It was profit-driven, and operated according to the logic of “market forces, internalized assumptions, and self-censorship.”

“The mass media,” they wrote,

serve as a system for communicating messages and symbols to the general populace. It is their function to amuse, entertain, and inform, and to inculcate individuals with the values, beliefs, and codes of behavior that will integrate them into the institutional structures of the larger society. In a world of concentrated wealth and major conflicts of class interest, to fulfill this role requires systematic propaganda. In countries where the levers of power are in the hands of a state bureaucracy, the monopolistic control over the media, often supplemented by official censorship, makes it clear that the media serve the ends of a dominant elite. It is much more difficult to see a propaganda system at work where the media are private and formal censorship is absent. This is especially true where the media actively compete, periodically attack and expose corporate and governmental malfeasance, and aggressively portray themselves as spokesmen for free speech and the general community interest. What is not evident (and remains undiscussed in the media) is the limited nature of such critiques …

… The essential ingredients of our propaganda model, or set of news “filters,” fall under the following headings:

the size, concentrated ownership, owner wealth, and profit orientation of the dominant mass-media firms;

advertising as the primary income source of the mass media;

the reliance of the media on information provided by government, business, and “experts” funded and approved by these primary sources and agents of power;

“flak” as a means of disciplining the media; and

“anti-communism” as a national religion and control mechanism.

These elements interact with and reinforce one another. The raw material of news must pass through successive filters, leaving only the cleansed residue fit to print.’ …

Journalists, they argued, were riddled with false consciousness:

…. The elite domination of the media and marginalization of dissidents that results from the operation of these filters occurs so naturally that media news people, frequently operating with complete integrity and goodwill, are able to convince themselves that they choose and interpret the news “objectively” and on the basis of professional news values. …

… Advertisers will want, more generally, to avoid programs with serious complexities and disturbing controversies that interfere with the “buying mood.” They seek programs that will lightly entertain and thus fit in with the spirit of the primary purpose of program purchases—the dissemination of a “selling message.”

… Economics dictates that they concentrate their resources where significant news often occurs, where important rumors and leaks abound, and where regular conferences are held. The White House, the Pentagon, and the State Department, in Washington, DC, are central nodes of such news activity.

If you prefer your Chomsky in cartoon form, this will do:

(Note the irony: Al Jazeera, of all organizations, produced that cartoon.)

What’s the Alternative?

Chomsky and Herman made an implicit argument. Were the media to cease manufacturing consent, the scales would fall from our eyes, and something better would emerge. That’s self-evident, or trivially true, as they say. Absent the media’s propaganda, we’d see the diminution of class and hierarchically-organized social orders and the spread and deepening of egalitarianism.

In 2008, Chomsky was asked whether the rise of the Internet might be significant:

He was wrong. We can now see, with miserable clarity, that politics were not “secondary at best.” We now have a keen insight into the alternative to manufactured consent.

Manufactured outrage

The Internet, and particularly social media, are a key cause of our breakdown into mutually hostile camps, each of whom views the other as wicked lunatics. We have failed fully to appreciate how revolutionary this technology is. It has introduced into our lives something the human race has never experienced, and we have neither developed institutions nor long-standing mores to help us cope with it.

None of us realized how much social media would change our relationship to the world, each other, and the truth. None of us had the sense to say, “Yes, this could be an enormously useful product, but it should be slowly introduced to humanity over a period of 200 years—not suddenly unleashed on an innocent public. It will take us at least two centuries to develop the laws, wisdom, and habits we need to make sure this technology is a boon to us, not our downfall.”

History doesn’t work that way. We had a revolution. We’re still having one. We’re now living in an epistemic and social world for which we’re unprepared.

You’re the center of the world

Why do you see so much journalism that infuriates you? So much obvious bias and mendacity? Because you click on it. It is your desire to be outraged and sensationalized that creates a market for the outrageous and sensational.

This is why we’re so polarized, politically, and it’s why we’re so profoundly ignorant about the world beyond our borders. These are serious problems: They make it impossible for us to govern ourselves, and they make for disastrous foreign policy.

Simply put, the advent of cable, satellite, the Internet, and other technological advances in media production have resulted in too much consumer choice. Consumers who are in no position to determine what’s newsworthy have been given the power to decide what they think is important. They’re in no position to determine what’s newsworthy not because they’re stupid, but because, by definition, they are news consumers. They wouldn’t be trying to find the news if they already knew it, would they?

News consumers now customize the information they receive to an extraordinarily high level of precision. They ignore everything else. Because stories are no longer bundled together in a single product—the nightly news, or a newspaper—the reader no longer has to slog through, or at least cast his eyes over, stories about high-level meetings on arms control negotiations before he can get to the sports page. We choose each item with a mouse-click—goodbye, list of boring economic indicators. Hello, American Civil War!

Advertisers can now measure precisely the amount of time you spend looking at any given page on the Internet. They’re interested in only one thing, and it’s not leaving you better informed or your country’s civic health. They couldn’t care less if you read the news backward instead of forward. The only thing they care about is this: “Did this page convince you to linger long enough to click on our ad and then buy our product?”

There’s a close, established correlation between the amount of time your eyes stay on the page and the probability of you clicking on an ad. If a page holds your attention, from the advertiser’s point of view, that’s good. They’ll show you more, in particular, of the thing engaged you. By reading that story, you’re telling advertisers how to get your attention, and it doesn’t matter if the attention is good or bad. It’s good for them.

Humans, we’ve discovered, prioritize news that terrifies or enrages them. We have a profound desire to know about these things. The reasons for this are probably self-evident.

Here’s how this affects journalism, as the New Yorker explains:

Chartbeat, a “content intelligence” company founded in 2009, launched a feature called Newsbeat in 2011. Chartbeat offers real-time Web analytics, displaying a constantly updated report on Web traffic that tells editors what stories people are reading and what stories they’re skipping. The Post winnowed out reporters based on their Chartbeat numbers. At the offices of Gawker, the Chartbeat dashboard was displayed on a giant screen.

Think of your attention the way you’d think of cold, hard cash. Advertisers now know everything about you. They know exactly which stories are alluring to you and where you are when you click on them. They know your history of online purchases and your zip code. They collect all of the demographic data that you willingly shed into the Internet, every day. They spend a lot of time analyzing it. They can judge with considerable confidence what kind of story is going to get you to do what they want. And what they want you to do is buy what they’re selling.

They don’t give a damn about the political consequences of the stories they’re using to sell their products. That, from their point of view, is what journalism is: “Stories they use to sell their products.”

Behavioral advertising

They want you to linger on that page until you notice an ad that has been chosen just for you, based on everything they know about you: one that tells you about a sale on power tools, or cropped skinny jeans; or a report, at the low, low price of US$1,459, about the online advertising market.

This is called “behavioral advertising.” It leads to a higher “conversion rate,” as they call a sale. It’s better than billboards, better than radio, better than the Goodyear blimp. There’s nothing like it.

Advertising used to be based on instincts and hunches, or at best a poll or a focus group. No longer. It’s based on you. You’re seeing ads that reflect the amount of time you’ve spent on every page you’ve ever cast your eyes upon and every link you’ve ever clicked.

They know the route you took to get at those pages. Did you get there by means of Drudge? By MSNBC? That’s information you willingly provide to big data whenever you buy something online. Do you get outraged when you read about Trump? Or the “coup against Trump?” Well, stories about Trump or the “coup against Trump” are what you’re going to see, every time you look at the news, until you’ve spent your last disposable dollar and you’re lathered into a violent frenzy.

A parallel you is living on a server farm in Oregon

Now consider this. Did you buy those skinny jeans? That information is going to be used to sell you health insurance.

How? Well, if you can fit into those jeans, you’re not overweight. (Data point 1.) They know, from Facebook, that you’re 39 years old. (Data point 2.) Tinder knows that you’re attractive (as opposed to just thinking you are). A sign of good health. (Data point 3.)

You shed data like dandruff. You’ve told Google maps you don’t have a long commute. That means you’re less likely to die in a car accident. (Data point 4.) You’ve never searched for, “I’ve just been diagnosed with glioblastoma.” An excellent sign. (Data point 5) Are you shopping for “x-treme paragliding gear?” Your life expectancy just went down. (Data point 6.)

All of this is information someone actually has, and you willingly agreed to share it. Yes, you did. You didn’t read that long contract very carefully, but that’s exactly what you agreed to do. Nothing on the Internet is truly free.

Information like that allows insurers to assess your life expectancy to a very high degree of accuracy. Assuming you’re young and healthy, you can now be bundled with other healthy people in your age bracket into a low-risk, low-cost health insurance pool. And you’ll love it. It will be a lot cheaper than what you’ve got now. (Skeptical? Fine, but note it down. When they debut the product, you can say, “I guess she was right.”)

A few years ago, the predictive algorithms became accurate enough to say, to a high degree of specificity, not only what kind of story people would click on, but what kind of product they would buy when they clicked on those stories.

The algorithms match the kinds of stories the customer likes, the kind of mood the customer likes to be in before he or she spends money, the customer’s tastes in consumer goods, his income, his purchasing patterns, and even the desires he isn’t consciously aware he feels, using a surveillance apparatus more totalitarian and dystopian than anyone ever had the imagination to foresee.

The odd thing is that everyone loves it, to the point they’re inseparable from its delivery vehicle—their phones. No one saw that coming, either.

Chomsky and Herman were partly right

Here’s what’s changed since the era of journalism Chomsky described and which you may remember fondly. Reporters and editors used to drive the news agenda. But for the most part journalists were, contra Chomsky, a liberal and dutiful class who strove earnestly to inform you about things they believed were important to liberal democracy and our civic health. They were not nearly as cow-like as Chomsky believes they were. Yes, they too were selling advertised products. No, they were not just selling those product.

Journalists don’t drive the news agenda at all anymore. You do. You click, the journalists give you more of what you clicked on, period. Occasionally, “news” companies break even by chasing #Trump or the #crazythingswokepeopledo. If they turn a profit, a high-minded editor might have the very rare privilege of paying a real reporter to do a real news story. Sometimes, this is supplemented by a philanthropist who gives the reporter a grant.

But there’s not much left of the massive news gathering and reporting apparatus that existed in America thirty years ago. The old guard, which liked to think it had a higher calling to report “the news,” has mostly died, been forced out, or overruled. What’s being sold to you now as the news is, for the most part, politics-flavored entertainment. This is what Chomsky thought it was. It wasn’t, when he described it this way, but it’s far closer now.

Every single story is now chosen by an editor who asks, “How likely are readers to click on this?”

The outrage du jour

I belong to an e-mail list composed of people who like to talk about national security issues. Because everyone on the list is human, though, as often as not the topic of discussion is the outrage du jour. There’s always an outrage.

A few weeks ago, the outrage involved the local hero in Iowa who raised a million dollars for a children’s hospital. Do you remember that one?

What started as a quest for a little extra beer money has evolved into a million-dollar gift to children in need. Carson King went viral last week with a homemade sign asking viewers of ESPN’s College GameDay to donate to his Venmo account so he could afford to stock up on beer. ….

By the end of the day, he’d accumulated more than USS$1,000—and quickly realized that the fast-growing cash would be put to much better use at the University of Iowa Stead Family Children’s Hospital, as opposed to his wallet.

And what does the media do? They scour our hero’s Twitter feed and find—miserabile visu!—that at the age of 16, he Tweeted something racist. They publish his adolescent Tweets, prompting ritual expressions of shame and apologies all around. But too late! Anheuser Busch drops its matching donation. Rough luck for the kids with cancer. The public is outraged, so it scours the reporter’s Twitter feed only to find that he too said something racist as a teenager. The newspaper bravely fires their reporter.

This story got the list hopping mad. “The editor who signed off on the piece should also be fired. Everyone who was involved should be fired. This isn’t journalism,” one wrote.

Not to be outdone, another one replied, “Whenever there is a major disaster like the Challenger explosion or 9/11, it is common for there to be a blue ribbon commission to look into how it happened and what can be done to prevent similar things in the future. We need such a commission to figure out what happened to journalism.”

Save the commission. I can explain.

Here’s what happened to journalism

It turns out that everything you hate about the media is your fault.

Let’s begin with foreign news coverage. I moved to Turkey in 2005. For a few years, I was able to support myself as a freelance writer. But after the financial crisis, almost every news outlet to which I had sold news articles about Turkey went under. Those that survived, and they were few, had a single message for me. “We’d be interested in publishing something by you, but we’re not interested in Turkey. Could you pitch something else?”

That year, I published an article in City Journal titled Less than Splendid Isolation.

The explanation for the decline of professional journalism is by now so familiar that it hardly needs rehearsing. (Internet, recession.) Harder to explain is the decline in the ratio of foreign to domestic news. The phenomenon is particularly striking if you live, as I do, in a country that has largely dropped off the media’s radar screen. It’s still more obvious if you’re a journalist: no one wants stories from Turkey these days.

Days before, the spokesman for the Turkish Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Committee had addressed a group of journalists in Istanbul. His topic—“Is Turkey drifting away from the West?”—struck me then, and still seems to me, important. But no one from a major US daily or news station attended—even though journalists from Britain, Belgium, Spain, and Greece did. “The Americans never come,” the organizer said. I could not give this story away to Americans. “Sorry, Claire,” wrote the editor of one news magazine, to whom I pitched the story. “We’re not interested in Turkey stuff.”

By 2012, by my rough count, about half of the Western journalists based in Istanbul had taken the bait and gone to work for Al Jazeera. They were the only ones hiring. Everyone else was shutting down, or “not interested in Turkey.” This was especially remarkable because the Syrian civil war was obviously becoming one of the most significant stories of the century, and just as obviously, Turkey was critical to this story.

In-depth international news coverage was vanishing from America’s mainstream news. What little made it into the news wasn’t sufficient to permit readers to grasp what was happening overseas or to form a wise opinion about it. Worse, a lot of it was just wrong. Factually wrong. The phenomenon was non-partisan. It was as true at The New York Times as it was at Fox. The way The New York Times was wrong was usually much more subtle, but it doesn’t matter: wrong is wrong.

This was odd. It was counter-intuitive. This was the era of the Internet, mobile phones, social media, citizen journalism. In theory, it was easier—far easier—to learn about the rest of the world. Why then, in practice, was news about the rest of the world disappearing?

Television, foreign news, and nuclear war

One might argue, and some have, that the phenomenon requiring an explanation is not Americans’ loss of interest in the news from abroad, but the brief period—during the Cold War—during which Americans did exhibit this interest. It is not a coincidence that this was the television era, and not just the television era, but the era of the broadcast cartel.

In 1963, NBC and CBS doubled the length of their nightly news programs from 15 minutes to 30. The networks were unsure whether there was an audience for a longer program. To prove their value, they began bulking up foreign coverage. Having a network of foreign correspondents, news editors believed, was proof of credibility, a sign that the news organization spared no expense to be on the scene wherever important events were taking place.

By the 1970s, the development of satellite technology made same-day coverage possible, and television had lost the Vietnam war.

As Garrick Utley wrote in 1997,

The mass public in the United States has never shown much sustained interest in what is happening abroad. Throughout the nation’s history, the American sense of self-containment has rarely been challenged, and then only by direct threats to US interests. The Barbary pirates’ “terrorism,” the War of 1812, and the sinking of the Maine were international punctuation marks of the nineteenth century. In this century, too, Americans’ interest in foreign affairs has generally been limited to war and the threat of war. The longest of these conflicts, the Cold War, coincided with the growth of television, from the late 1940s to the late 1980s.

During this period, however, for the first and last time, Americans took a keen interest in news overseas. Utley believes this was because “nuclear weapons were aimed at American communities.” Could that be?

No. This hypothesis doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. If Americans paid attention to news from overseas chiefly because nuclear weapons were aimed at their communities, they would be more keenly interested in news from abroad now than they were then.

Our loss of interest in the prospect of nuclear war is one of the great mysteries of the modern era. Regularly, I see such constructions as this in the media: “Back during the Cold War, when we were threatened with the prospect of nuclear annihilation … ” As if, truly, this prospect had come to an end.

Russia regularly threatens to vaporize American cities. The number of countries capable of annihilating the United States has grown. The major powers have been upgrading their arsenals. They have been testing, producing and deploying new weapons with an uncertain effect on traditional deterrence doctrines. Arms control efforts have serially failed: a qualitative global nuclear arms race is now underway; the world’s nine declared nuclear states are spending hundreds of billions of dollars to improve their arsenals. Tensions between nuclear-armed states are sharply on the rise. India, Pakistan and North Korea are enlarging their nuclear arsenals as fast as they can. Key treaties have been broken or are under threat. The US has withdrawn from the INF and Open Skies Treaty. START is headed for a similar fate. The United States and Russia retain launch-under-attack postures that increase the risk of miscalculation. The international system has been profoundly destabilized. No, we are now more at risk of nuclear war than ever before in the history of the human race.

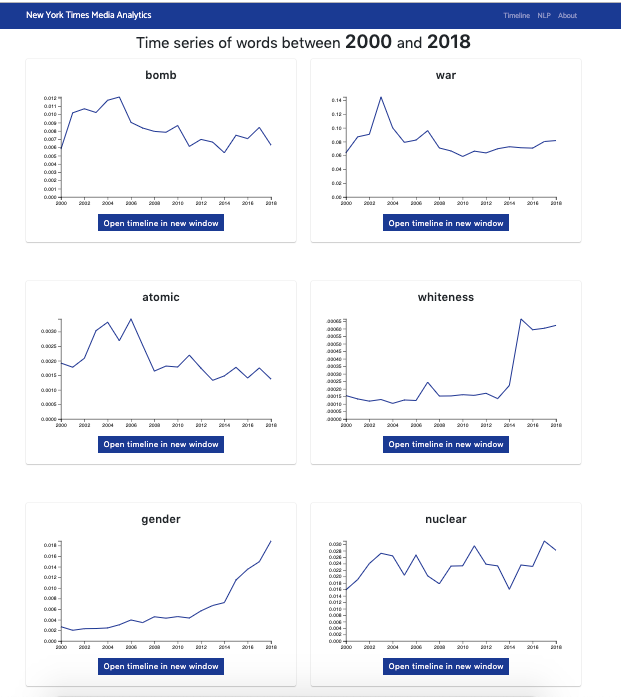

Yet Americans no longer fear nuclear war as they once did. An analysis of word-use frequency in The New York Times suggests we have larger preoccupations:

(Note that the values on the y axis are not held consistent.)

Perhaps it’s simply a matter of acculturation: We’ve managed to go this long without a nuclear exchange, people think, so it can’t happen.

Or perhaps it’s because we no longer receive news from abroad.

Perhaps Garrick Utley has it exactly backward.

The decline of broadcast news

In 1989, ABC broadcast 3,733 minutes of foreign news into American households. By 1996, the number had declined to 1,838 minutes.

During the Cold War, every major American newspaper and television station covered foreign news, particularly from the Soviet Union and Europe. American television networks set the standard for global news coverage and drove the global news agenda. All the major networks had bureaus across the globe, staffed by correspondents who had long been on the ground. Whether they were in Berlin, Cairo, Istanbul, or Moscow, they knew their region, they knew the people, they spoke the local languages, and knew the history of the stories they covered.

Even small local papers had bureaus overseas. They hired foreign correspondents, paid them a living wage, and sent them—and their families—to foreign countries with generous expense accounts and housing allowances and a budget for interpreters and fixers. Their reports ended up on the papers’ front pages, or, in the case of television news, at the top of the hour.

What happened between then and now?

The big three broadcasters were a cartel. In 1980, more than 90 percent of Americans watched ABC, NBC, or CBS during prime time. With essentially captive audiences, they could afford to compete against each other to do expensive things, like covering the news abroad. By 2005, the number had fallen to 32 percent.

The explanation for the demise of broadcast news is technological. The rise of cable and satellite networks, coupled with the widespread penetration of the remote control device, offered viewers the chance to see something else. New broadcast networks, such as Fox, Telemundo, Univision, and Azteca, cut into the big three share—but overall, the audiences were lost to cable, satellite, and the VCR.

Consumer and advertiser spending on mass media has remained relatively constant. But these resources are now spread over 90 channels instead of three. Voilà: there are no resources left for foreign news coverage.

Foreign news coverage is the most obvious example of “how competition made television much more entertaining but much less good at conveying the news.” But it’s the same across the spectrum: The resources for reporting on the United States itself are similarly spread thin.

It’s common to say that people have lost confidence in the media because the media has become untrustworthy. It’s much more accurate to say that the media has become untrustworthy because doing good reporting is resource-intensive. There simply aren’t enough people who want to read (or watch) good reporting to make it profitable. Given the choice between carefully reported, professional, fact-checked news programs and 120 more amusing shows, people have voted with their remote control. “The news” now has to compete with “the best television shows ever made, streaming in on Netflix,” and everyone likes watching that show about the woman with dragons a lot more than watching the news.

Don’t blame Fox, by the way. I know everyone thinks Fox has stolen their parents and turned them into drooling zombies, but no one watches Fox, either. The percentage of Americans who get their news from Fox is remarkably small: In 2022, the audience for their prime time news slot was 2.1 million people—less than one percent of the adult population of the United States.

As for the decline of print media, this one’s obvious: It’s the Internet.

It’s damn good for CBS

It’s one outrage after another, isn’t it? What the media did to those Covington boys, right? Not just obscene, but painfully stupid. For days, journalists of every political disposition could not stop banging on about those Covington kids in MAGA hats who harassed a Native American veteran at the Lincoln Memorial. The media managed somehow to turn that story into the week’s most important news and a sign of our terrifying times even though it was not true. An equal number of column inches were then devoted to denouncing the journalists who denounced the teenagers. The media has persuaded a whole generation of kids that we will all, literally, boil to death in eleven years, even as it systematically ignores the growing threat of nuclear annihilation.

And let’s not forget: the media put Trump in the Oval Office. Chasing ratings, it gave him two billions dollars worth of free coverage. “It may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS,” said Les Moonves:

Man, who would have expected the ride we're all having right now? ... The money's rolling in and this is fun. I’ve never seen anything like this, and this going to be a very good year for us. Sorry. It’s a terrible thing to say. But, bring it on, Donald. Keep going.

The epistemological crisis

France’s Centre d’analyse, de prévision et de stratégie and the Institut de recherche stratégique de l’École militaire recently wrote an excellent report describing the scope of the problem. They use the phrase “epistemological crisis.” That there is such a crisis is well-known among people who work in the media and the military, but I don’t believe it has truly filtered down to most media consumers, who still believe they’re savvy enough to distinguish real from fake reports.

Most people now get their news from social media and podcasts, not from established broadcasters or newspapers. (And most people don’t realize that established newspapers now rely on Twitter for a very significant proportion of their foreign news coverage—have you noticed how often the dateline, in newspapers like the Times and the Post, is not the city or country in question?)

People haven’t fully internalized how dysfunctional this situation is—yet. They still think they’re getting a pretty good sense of what’s true and what’s not from what they read on the Internet. Trump’s supporters get their news from Breitbart, Fox, and right-wing social media accounts (of which a significant proportion are Russian). The rest of America reads the New York Times and the Washington Post—who are getting their news from Twitter—and follow left-wing Twitter accounts. (a significant part of the far-left on the Internet is also Russian: They’ve just dusted off the COMINTERN files.)

People express disgust and distaste for “the media” and claim that the opposite side is fake. They don’t yet fully realize how fake it is—and how much of what they think of as their own side is fake.

And if it’s bad now, just wait until deep fakes go mainstream.

How to get better journalism

Here’s how to make journalists stop doing things like “publishing a vaguely offensive thing that a local hero said on Twitter when he was sixteen.” It’s so simple you wouldn’t believe it.

Never, ever click on stories about that kind of thing.

Think of your attention the way you’d think of cold, hard cash. They’re measuring the amount of time you spend looking at stories like that. The amount of time your eyeballs spend on the article or articles about the article is all they care about. By “they” I mean advertisers. If something gets your attention, they’ll show you more of it. They’ll show you more, in particular, of the thing that most enrages you. By reading that story, and stories about that story, you’re telling advertisers how to get your attention, and it doesn’t matter if the attention is good or bad. It’s good for them.

This isn’t a conspiracy theory of any kind, as fantastic as it sounds. You’re seeing the news you’re seeing because you want to see it. Your fantasies are creating it.

Your outrage has been successfully manufactured.

Privacy and authoritarianism

It’s not an accident that privacy and liberal democracy find themselves in their death agonies at the same time. Liberal democracy is rooted in the prioritization of individual rights over collective rights, and this technology is eroding our sense of the individual. A whole generation of adults has now grown up without any natural, robust, and intuitive sense of “privacy.” This may well be one reason why collectivist politics strike millennials as appealing, rather than repulsive. Of course we’re all one big collective, we’re all hooked up to the same machine, right?

In the West, so far, these enormously elaborate surveillance powers have not yet been used in a manifestly totalitarian fashion, as they are in China. But living like this primes us to accept ever-greater authoritarian incursions, ones that only recently would have appalled us. Nor can we opt out. It’s no longer possible to have a professional life without an Internet and social media presence.

We now, each of us, leave a permanent, indelible, daily record of our thoughts—a record more truthful than any written diary has ever been. If you want to peer into my soul, have a look at my search history. Think how useful this information would be to despots of every stripe. I leave a record of every political, economic, or spiritual question I ask myself, large or small. You do, too. It would hardly take long to identify dissidents and thought-criminals this way, would it? What couldn’t a despotic state do with such a detailed record of every citizen’s preoccupations, curiosities, and thoughts?

That this is an incipient instrument of authoritarianism or totalitarianism is so obvious it barely needs stating, yet we rarely think about it. Our notions of privacy, human dignity, independent thought, and freedom of expression have to varying degrees been rendered obsolete. How can liberalism, with its emphasis on the self-contained individual, survive the eradication of privacy?

Furthermore, you no longer have to throw dissidents in jail—or do anything especially violent to them—to minimize the chances they’ll get in your way politically.

The new propaganda

Peter Pomerantsev’s work on Russia is a particularly insightful treatment of the relationship between propaganda and the new authoritarianism. His parents, Soviet dissidents, were harassed and eventually deported by the KGB for “the simple right to read, to write, to listen to what they chose and to say what they wanted.” When he wrote that book, he observed that his parent to a large extent had those rights in Russia. But they’re meaningless. More information has not meant more freedom.

The Soviet Union controlled the narrative by silencing its opponents. Putin does this, too, but far more rarely. Instead, Russia confuses its population—and its adversaries’ populations—by snowing them with lies, half-truths, alternative narratives, and alternative facts. (I am not sure whether Kellyanne Conway chose the phrase “alternative facts” in deliberate homage, or whether she happened upon it independently. Probably the latter, but the phrase isn’t a mistake.)

Pomerantsev left Russia in 2010, dismissing Russia as a “sideshow, a curio pickled in its own agonies.” But it wasn’t.

Suddenly the Russia I had known appeared to be all around me: a radical relativism which implies truth is unknowable, the future dissolving into nasty nostalgias, conspiracy replacing ideology, facts equating to fibs, conversation collapsing into mutual accusations that every argument is just information warfare … and just this sense that everything under one’s feet is constantly moving, inherently unstable, liquid.”

Dissenters are no longer silenced so much as they are drowned out. States have moved, as Tim Wu puts it, from “an ideology of information scarcity to one of information abundance.”

In a review of Pomerantsev’s work, Douglas Smith writes,

Russia was the birthplace of what he calls “pop-up populism,” pseudo and forever mutating notions of what, and whom, constitutes the “people,” all artfully curated by media and political strategists to meet specific goals. This amorphous mass is assembled around some notion of the enemy—in the Russian case, first oligarchs, then metropolitan liberals, and, most recently, the West. None of this need be coherent. What matters is connecting with people on a profoundly emotional level. And, in what is among the most disturbing aspects of the book, thanks to social media, our deepest emotions are not merely online and for sale, but they can be manipulated in extremely precise ways without our knowing it.

In this new world, censorial limits on information have given way to “censorship through noise” and “white jamming,” a tactic associated with the Russian media analyst Vasily Gatov that involves surrounding people with so much conflicting and confusing information — information intended to play to their fears and cynicism — that they are left feeling helpless and apathetic and convinced the only solution to their problems is a strongman, be it Putin, Duterte, Bolsonaro, or Trump.

If the metaphor of a marketplace of ideas suggested that the truth will always win, the new information environment suggests the opposite. Truth is usually complex, partial, and difficult to ascertain. Lies are easy, simple, and crude. In this marketplace of ideas, the lies are less expensive than the truth.

And the lies win.

Wikipedia tells me that Carlyle was the first to use it to describe the press. I haven’t confirmed this, but it’s probably true: It’s somewhere in Sartor Resartus. I find Carlyle unreadable, so you’ll have to check for yourself.