WHAT WOULD MAKE YOU READ THIS?

I MET my friend Phiroze in a bookstore in Paris when I was nineteen, and we’ve since had a long and storied friendship. For more than thirty years, unless we’ve been in the same city, we’ve exchanged letters regularly—and, in recent years, emails.

He’s been on the mailing list for this newsletter since its debut. I therefore assumed he was reading it. But yesterday, he dropped me a note. “For the first time I read one of these things. I quite liked it.”

I nearly plotzed. Phiroze. I’ve been sending him newsletter after newsletter, but he hasn’t been reading them? And this is my friend—someone already disposed to read letters from me. He has a long, proven history of reading letters to me.

Who else on my mailing list isn’t reading this? How do I persuade them that if only they’d try it, they’d like it?

“Why didn’t you read it before?” I asked him. He wasn’t sure. But he liked it.

I think your tone is very well suited to your audience, warm, chatty, friendly, knowing, post graduate, a little self deprecating but then suddenly confident and informed.

This response suggests the newsletter itself isn’t displeasing—but for some reason, people don’t open it.

Perhaps people are so deluged with information that the arrival of a newsletter feels like a burden, a demand for attention that no one has left?

Or might readers fear it will be boring? Or depressing?

What can I do, I wonder? Better headlines? A different color? I’ve tried, as you see, changing the color scheme to red. More cheerful.

Any idea what else I could do to persuade people just to give it a chance?

Could I ask you to try sharing it again, with your friends, with a note reassuring them that it isn’t boring?

FAITHFUL READERS: PLEASE SKIP TO THE JUMP

IF YOU’VE been reading since the beginning, just skip this part. This is for those of you only now decided to read this newsletter.

Welcome, new readers! Let me explain what you’ve found. This is a newsletter, which like any newsletter treats the news—that is, current events—from the perspective of an expatriate, a scholar of international relations, and an ardent defender of liberal democracy.

It’s an extremely alarmed perspective. It can, in truth, be depressing. But there’s good news: The future is uncertain. Nothing is written. The future depends what we, ordinary men and women, decide to do about it.

But this is not just a newsletter.

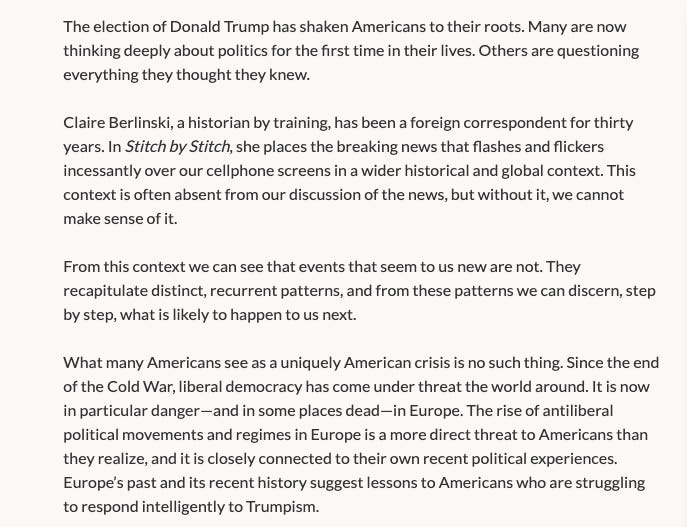

Since 2016, I’ve been working on a book about the New Caesars, the rise of illiberal democracy, and the death of freedom. The project has been wholly crowdfunded by my readers. Here is the précis:

(Doesn’t that sound interesting? If you’d like to contribute, please do.)

This book now exists, as a manuscript that requires some proofreading, but is basically done. I could just publish it, as a traditional book.

But I’ve decided instead to publish it in this newsletter. You will discover that interleaved with my commentary on the news, there is a book. You don’t have to read it cover-to-cover to follow it, but if you’d like to read it that way, you can: It has a unified, coherent structure. I’m rewriting a bit as I go along to ensure each newsletter also stands on its own—I assume that many readers will read them that way, and, I hope, share them—but basically, I’ve already written most of what you’ll read. I’m also adding material that’s in the news; after all, it’s a news letter.

You’ve caught this train mid-chapter. You can read the first two parts of Social Media and the New Man here:

You can read the introduction to the book here:

And the first chapter, here:

You might be interested in this chapter, too:

But you don’t have read any of that. You can also start right here, today.

The newsletter is completely free, but it’s entirely supported by my readers’ voluntary contributions—and if you find it useful or enjoyable, I’d sure be very grateful for yours. Those of you who contribute make it possible. So if you’re reading this and you haven’t contributed, please thank the people who did, because they’re subsidizing you.

If you’d like to contribute to this historic literary experiment and be a respectable, paying member of society, however, here are the links to contribute via GoFundMe, Paypal, and Patreon. (I should remember always to put these at the beginning of the newsletter, in case you get bored before the end).

Or let me know if you’d prefer to send a check.

FAQ

Claire, why are you publishing a book as a newsletter? This is unwieldy and hard to follow. I want a book, with pages that turn.

No worries. When it’s done, contributors get a copy of the book. A printed one. It will be better owing to my readers’ enthusiastic copy-editing.

But why are you doing this at all?

Because it’s an experiment in publishing—a delicate undertaking, one never before attempted in the history of literature:

Yes, but why?

Because I’ve convinced myself my own arguments—which you can read by following the links above—are correct. I’m very worried about the future of liberal democracy. I’d like this book to be my small contribution to preserving it. I don’t think it can be of any use at all, though, if no one reads it.

Why wouldn’t people read it?

Well, one of the key arguments I make is that the Internet has profoundly changed the way we understand political arguments, our attention spans, our cognition, and the nature of literacy. The truth (though most of us are too embarrassed to admit it) is that it is growingly difficult for anyone young or middle-aged to read an old-fashioned printed book, cover-to-cover, save under punishment and duress.

This does not mean we no longer read. I spend no less time reading than I used to. In fact, I spend all my time reading, as I have since I was a toddler. But I now read almost everything on a screen, and the way I read is different.

Even when I read a printed book, I find myself reading it differently. The absence of hyperlinks frustrates me. I can’t instantly check the sources, which I’m now accustomed to doing. Footnotes seem to me so inefficient. I’m irritated by my inability to search for keywords.

My brain has now adapted to favor the screen and the Internet over print, and almost certainly yours has, too. The human brain is highly plastic; new connections form among neurons; the internal structures of the synapses change; synapses strengthen or weaken; old neurons are pruned; functions can be transferred from a damaged (or disused) region of the brain to another. It’s a matter of habituation and the environment. When I first began the shift from print to the screen—anyone else remember word processors?—it was the opposite way around: I found it far more difficult to read from a screen. I well remember complaining of it and printing out documents so that I could understand them better.

OK boomer.

Nope, I was born in 1968. But basically, yes.

But I still don’t get it: Why are you sending me a newsletter?

Because I just have a grim feeling no one will read yet another book about what’s happened to liberal democracy. My most devoted readers—the ones who’ve chipped in to GoFundMe or support me on Patreon—might read it to be sure they got their money’s worth, but this means the audience for the book will be very limited. There’s no way the book will have any impact like that.

The market is already saturated with books about this. Some of them are very good, too, but who reads them? Far more people read Scott Adams than Levitsky and Way. (I know because whenever I point out, on Twitter, that we seem determined to enact every stage of Competitive Authoritarianism, someone pops up and tells me I should read that fraud Scott Adams, and I want to rend my garments and wail.)

This pains me, but it’s the way it is. You’re more likely to read and share something on a screen than you are to read and share a printed book. Publishing a printed book will ensure everything I say disappears into oblivion.

This newsletter might disappear, too. But it will have a fighting chance.

Is everything in the newsletter out of date, then?

No! This is the beauty of it. I found, writing this book, that events kept overtaking me. I’d finish a draft only to realize that the first chapter already seemed like the distant past. I at first thought this was my fault—for having tied the first chapter to an obviously evanescent event—but when it happened several times running, I began to suspect it wasn’t me. It was history.

History, and the pace of change, are now moving uncommonly quickly. This happens at times—it would have been hard to write a book about current events during the years from 1789 to 1795, for example, without being overtaken by events.

I revised the book many times before realizing that the problem wasn’t me, but something external. This was spooky. I resisted this idea for a long time, thinking it was obviously narcissistic. Our times could not be that interesting, I thought; every generation must think that, there’s nothing new under the sun. But increasingly, I’ve been persuaded that this is a genuinely revolutionary moment—as significant as the French or the Sexual or the Scientific Revolution. The evidence of it just keeps coming in. We live in a Chinese curse.

But the bright side of living in interesting times is that they are, at least, interesting.

So I’m updating the book as I go along, in light of the news and in light of the questions you send me.

Will this work, as a book or as a newsletter? I don’t know: We’ll find out together.

But I just couldn’t bear the thought of no one reading it, though, especially because so many of my readers contributed to the book campaign. That really touched me. I owe it to them to do something that makes some kind of useful difference and helps us better to think through the problems we’re facing.

But is this book intellectually inferior because I’m reading it on a screen?

Absolutely not. That’s silly.

Why do I feel that way, then?

Because having a taste for printed books is a mark of rarified class and social status.

Are you sure that’s the only reason? I feel guilty, somehow, for reading this on a screen.

Yes, I’m sure. I could print it all out right now and show you that it’s the same thing as a book. The ideas are no better or worse. There’s no reason to think reading this is an intellectually inferior experience because it’s on your screen.

But it’s in bite-sized chunks. It’s not painful to get through it.

There’s no shame in that. Dickens serialized his books, too. That it’s interspersed with contemporary commentary makes it look like a blog, but deep down, it’s a book. And I really think you’ll like it, if only you’d read it.

Okay, Claire, I’ll give it a try.

Great! It’s best if you sign up now so you never miss a newsletter. That way all my references to arguments I’ve made in previous newsletters will make sense. I’ll recapitulate the context briefly as I go along, but I don’t want to do that excessively, for it would punish by repitition the faithful readers who’ve already heard those arguments, and they’re the ones who least deserve it.

What if I don’t like it, though?

If you don’t like it, the “unsubscribe” button is at the bottom of this e-mail. I won’t be offended. I won’t even notice, frankly.

WELCOME BACK, FAITHFUL READERS

I MAKE a point of not noticing who is and isn’t reading this newsletter.

But I could, if I wanted to, learn a lot about who you are. To send this newsletter, I use a handy application called Substack. Substack eagerly offers me information about you so that I can better target you with marketing and figure out what you like. It would take me only a few clicks to figure out what, exactly, your name is, where you are, whether you’re reading this carefully or just skimming, how often you open my newsletters, how many times you open them, and what links you click on once it’s open.

Should I ever have advertisers, that data would be of interest to them. Substack offers all of it to me, for free. They asked me no questions at all about how I planned to use it. No one thinks that’s strange. No one thinks that should be illegal.

But I shouldn’t know this, should I? Did you realize you were signing up to share that with me? It is sinister and dystopian. And of course, it’s exactly the same way with every other website or newsletter you visit or read.

I’m fully compliant with the GDPR, but I still have access to all of this, and we now accept this as a matter of course. I discuss this in the previous installment. This is how Americans have come to live in two separate realities, each not only with their own interpretation of politics, but with their own facts.

Now, I don’t look at your data. You may have agreed to share it with Substack, but you didn’t agree to share it with me, and it’s not my business. But mind, this scrupulosity puts me at a disadvantage against competitors who would study your data as a matter of routine. Not a big deal for me, because I have no competition. I enjoy a natural monopoly on Claire Berlinski. But what if I were selling cars, or plane tickets? I’d have to invade your privacy, or I’d go out of business.

These are serious questions, and we hear vague murmerings from time to time about this being a problem—maybe even a massive, quasi-theological problem—but we aren’t yet even in the time zone of thinking about this seriously. We haven’t yet had the hundreds of years we’ll really need to think this through.

PRIVACY AND PRECURSOR AUTHORITARIANISM

It’s not an accident that privacy and liberal democracy find themselves in their death agonies at the same time. Think about it: Liberal democracy is rooted in the prioritization of individual rights over collective rights, and we’re allowing our natural sense of the individual to disappear. In the West, so far, these enormously elaborate surveillance powers have not yet been used in a manifestly totalitarian fashion, as they are in China. But living like this primes us to accept ever-greater authoritarian incursions, ones that only recently would have appalled us.

We can’t opt out. It’s no longer possible to have a professional life without an Internet and social media presence. So a whole generation of adults has now grown up without any natural, robust, and intuitive sense of “privacy.” This may well be one reason why collectivist politics strike millennials as appealing, rather than repulsive. Of course we’re all one big collective, we’re all hooked up to the same machine, right?

We now, each of us, leave a permanent, indelible, daily record of our thoughts—a record more truthful than any written diary has ever been. If you want to peer into my soul, have a look at my search history. Think how useful this information would be to despots of every stripe. Here’s a random sample of “What Claire Berlinski secretly thinks.”

I leave a physical record of every political, economic, or spiritual question I ask myself, large or small. You probably do, too. It would not take long to identify dissidents and thought-criminals this way, would it? What couldn’t a despotic state do with such a detailed record of every citizen’s preoccupations, curiosities, and thoughts?

That this is an incipient instrument of authoritarianism or totalitarianism is so obvious it barely needs stating. Our notions of privacy, human dignity, independent thought, and freedom of expression have to varying degrees been rendered obsolete. How can liberalism, with its emphasis on the self-contained individual, survive the eradication of privacy?

(Even if you don’t find the privacy implications disturbing, don’t you think the people using it should be paying you for all your data?)

MORE INFORMATION, LESS FREEDOM

WHAT’S MORE, you no longer have to throw dissidents in jail—or do anything especially vulgar or violent to them—to minimize the chances they’ll get in your way politically.

Peter Pomerantsev’s work on Russia is the best and most insightful treatment so far of the relationship between propaganda and the new authoritarianism. His parents, Soviet dissidents, were harassed and eventually deported by the KGB for “the simple right to read, to write, to listen to what they chose and to say what they wanted.”

They have those rights in Russia now, to a large extent. But they’re meaningless. More information has not meant more freedom.

The Soviet Union controlled the narrative by silencing its opponents. Putin does this, too, but far more rarely. Instead, Russia confuses its population—and its adversaries’ populations—by snowing them with lies, half-truths, alternative narratives, and alternative facts. (I am not sure whether Kellyanne Conway chose the phrase “alternative facts” in deliberate homage, or whether she happened upon it independently. Probably the latter, but the phrase isn’t a mistake.)

Pomerantsev left Russia in 2010, dismissing Russia as a “sideshow, a curio pickled in its own agonies.” But it wasn’t.

Suddenly the Russia I had known appeared to be all around me: a radical relativism which implies truth is unknowable, the future dissolving into nasty nostalgias, conspiracy replacing ideology, facts equating to fibs, conversation collapsing into mutual accusations that every argument is just information warfare . . . and just this sense that everything under one’s feet is constantly moving, inherently unstable, liquid.”

Dissenters are no longer silenced so much as they are drowned out. States have moved, as Tim Wu puts it, from “an ideology of information scarcity to one of information abundance.”

In a review of Pomerantsev’s work, Douglas Smith writes,

Russia was the birthplace of what he calls “pop-up populism,” pseudo and forever mutating notions of what, and whom, constitutes the “people,” all artfully curated by media and political strategists to meet specific goals. This amorphous mass is assembled around some notion of the enemy — in the Russian case, first oligarchs, then metropolitan liberals, and, most recently, the West. None of this need be coherent. What matters is connecting with people on a profoundly emotional level. And, in what is among the most disturbing aspects of the book, thanks to social media, our deepest emotions are not merely online and for sale, but they can be manipulated in extremely precise ways without our knowing it.

In this new world, censorial limits on information have given way to “censorship through noise” and “white jamming,” a tactic associated with the Russian media analyst Vasily Gatov that involves surrounding people with so much conflicting and confusing information — information intended to play to their fears and cynicism — that they are left feeling helpless and apathetic and convinced the only solution to their problems is a strongman, be it Putin, Duterte, Bolsonaro, or Trump.

If the metaphor of a marketplace of ideas suggested that the truth will always win, the new information environment suggests the opposite lesson. Truth is usually complex, partial, and difficult to ascertain. Lies are easy, simple, and crude. In this marketplace of ideas, the lies are less expensive than the truth—and the lies win.

THE WORLD WE CAN STILL REMEMBER

A PAUSE for nostalgia. My youth has vanished into the mists of time. No, really, it has vanished. No one no knows what I did, for example, during the summer of 1995, when I disappeared in India. My communication with the West was limited to an occasional fax I managed to send my parents every few weeks from various village PTTs. No one will ever search my Twitter feed and discover that while I was there, I said something offensive.

Nor did I know what the rest of the world was thinking. This was, I suppose, the downside. When I returned to Bangkok that fall, I had no idea what had happened in my absence:

“I can’t believe it!”

“Yeah. It’s really sad.

Jerry Garcia’s dead?

You will never know what I did that summer unless you ask me. There is no way to reconstruct my journey. There’s no way to figure out where I stayed, to whom I spoke, with whom I traveled. I took no photos. I posted nothing on social media. I wasn’t “taking a break” from social media. Social media didn’t exist. The human norm was privacy.

No one could take a journey like that now.

No young person could now understand the feeling of being that free, and thus probably couldn’t know to yearn for it. Our identities are now nearly inseparable from our digital footprints.

But Claire, we have laws against using that data in an authoritarian way. We’re safe.

You sure?

AMERICA FIRST VERSUS REALITY

TRUMP and other populists can bang on all they want about the failure of “globalism” and the wonders of nationalism, but this just means they’re inhabiting a fantasy world and they wish you to share it. Globalization isn’t an ideology. It’s a fact. The world has become globalized. The technologies that have made this possible—the Internet and container shipping—are not going to go away.

The past decade has seen a global authoritarian revolution. These political transformations have been taking place in a highly similar way around the world because they emerge from the same, global, economic and technological forces. A very particular form of authoritarianism is emerging from them—an entertaining but empty form of democracy denuded of everything that makes democracy meaningful.

This is the New Caesarism. Caesarism, because it arises in circumstances reminiscent of those that destroyed the Roman Republic. The founders of the United States, avid students of classical history, knew the story of its downfall. They fully understood that democracy and freedom were not identical, and indeed in tension. They grasped the implications of this. “Of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics,” Alexander Hamilton warned, “the greatest number have begun their career by paying an obsequious court to the people; commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.” What Hamilton feared is precisely what is now happening to established constitutional orders the world around—including ours.

New because it is a genuinely new species of Caesarism, one even the founders could not have imagined. We have been slow to recognize the threat it poses because in key respects it genuinely is unlike anything humanity has seen before. It is something new under the sun.

We’re confused because these regimes are genuine democracies, where rulers enjoy real popularity. But liberal rights and freedoms have vanished in them—and the ruler’s popularity is based on a system of surveillance, propaganda, and thought control that we’ve made possible through the invention of the 21st-century’s revolutionary new communication technologies.

The New Caesars are learning from each other. The Internet has made their ideology—and they do have a coherent ideology—virulently contagious. Such regimes, Putin’s in particular, harness formidable state security apparatuses to spread their form of governance. The New Caesars employ similar, almost stereotyped, strategies to gain power and keep it.

In the global war between liberal democrats and the New Caesars, Europe is the critical battlefield. Authoritarian movements and political figures now endanger Europe’s democracy and its long post-war peace, the basis of the post-war global order. We take this order, the only world our generation of Americans has ever known, for granted, even though we can’t flourish and may not survive in its absence. The battle to control Europe’s future urgently demands our attention, both for this reason and because it shows us what to expect next.

But at the very moment events abroad most demand our attention, we have none to give. Since the end of the Cold War, the United States has retreated to an archipelago of cultural isolationism, marked by a progressive loss of interest in the world. In the era of Walter Cronkite, more than 40 percent of broadcast news was international. This figure is now barely four percent. Trump’s election accelerated our path to national solipsism by transforming the White House into a near-preternatural attention vortex: None of us can take our eyes off of it.

We can’t afford this self-absorption. The real story is not Trump. He is a symptom, not a cause. The real story is the rejection of liberalism in the West—and this is the most momentous story of the millennium, for if these ideals fail in the West, they stand no chance anywhere.

Because we have paid so little attention to the global authoritarian revolution, we’ve failed to learn from it. This is why we lacked the imagination to envision Russia’s interference in the 2016 election. It’s why we find ourselves daily astonished by the Trump presidency, even though he is playing from a handbook—one with predictable rules.

Understanding what has happened abroad in these past two decades is key to understanding what is happening to us now. The daily news cycle and its associated culture encourage us to understand these events and their relationship to our recent experiences only poorly and superficially. But when we look more closely, we see that Americans are not living through unprecedented events—not whatsoever.

Our constitution, culture, and geography are safeguards—they are what will save us, if we can be saved—but we can’t repose in them all our confidence. Turkey, too, had strong constitutional, cultural, and geographic safeguards. They failed. Our safeguards should have kept Trump out of the Oval Office in the first place. They didn’t.

OF NOTE

President Trump Says He Is Weighing Putin's Invitation to Russia Victory Day Parade

Pro-Orban media moguls who destroyed Hungary’s media now targeting European outlets

INTERGENERATIONAL MOBILITY OF IMMIGRANTS IN THE US OVER TWO CENTURIES

Co-founder of Syrian 'White Helmets,' James Le Mesurier, found dead in Turkey

MEANWHILE, don’t forget! Please tell your friends this newsletter isn’t boring:

And don’t be a burden on other readers!

PS: LETTERS FROM MY READERS

SOME of you have sent me very good emails with excellent questions and criticism. (Haven’t forgotten yours, Eric.) I think I’ll give over the newsletter, once a week, to your letters and my answers. On Friday, perhaps.