This is the third part of an n part series addressing Shawn Rosenberg’s recent claim—and many other such claims, ancient and new—that democracy is doomed.

For those who don’t have time to read Part I or Part II, here’s the abstract of Rosenberg’s paper, a submission to a forthcoming book titled Psychology of Political and Everyday Extremisms:

I argue, unlike many, that the rise of populism is not simply a passing response to fluctuating circumstances such as economic recession or increased immigration and thus a momentary retreat in the progress toward ever-greater democratization. Instead, I suggest current developments reflect an underlying structural weakness inherent in democratic governance, one that makes democracies always susceptible to the siren call of right wing populism. The weakness is the relative inability of the citizens of the modern, multicultural democracies to meet the demands the polity imposes upon them. Drawing on a wide range of research in political science and psychology, I argue that citizens typically do not have the cognitive or emotional capacities required. Thus they are typically left to navigate in political reality that is ill-understood and frightening. Populism offers an alternative view of politics and society which is more readily understood and more emotionally satisfying. In this context, I suggest that as practices in countries such as the United States become increasingly democratic, this structural weakness is more clearly exposed and consequential, and the vulnerability of democratic governance to populism becomes greater. The conclusion is that democracy is likely to devour itself.

And now a word from our sponsor

I was going to use this issue to explain at length why Rosenberg might well be correct—then I thought, “Why? You’ve already written a book about it.”

When I remembered that, suddenly, the point of this newsletter became clear to me.

The book has been titled, Stitch by Stitch: The Unraveling of the West, and Brave old World: Europe Revisited, but I’ve settled on The Rise of the New Caesars and the Death of Freedom. Some of you know about it already, because you contributed to my GoFundMe campaign.

Hey, that’s right! Claire—what happened with that? Where’s the book?

Right here. It’s on my desktop.

Why can’t we read it?

You’re about to. In fact, I’ll be publishing it on this newsletter.

Why do I need to read a newsletter? Why can’t I just read the book?

Because you won’t.

Why you won’t read my book

Based on trends in the publishing world and my previous experiments with publishing my own books, I believe that no matter what I call this book, you will not read it. Not even if you sent me money to write it.

This isn’t just morbid rumination. I’ve got excellent reason to think this.

First, book reading is in decline:

From the same source:

33% of high school graduates never read another book the rest of their lives and 42% of college grads never read another book after college. 70% of US adults have not been in a bookstore in the last five years and 80% of US families did not buy or read a book last year.

I write about this phenomenon in my book. I consider it key to understanding why liberal democracy is in jeopardy. But now we’ve got something like the Barbershop Paradox. What is the point of writing a book explaining why it won’t be read?

If the odds that you’ll read my book are small, they’re even smaller if I self-publish it. This is important, because Rosenberg argues that the ease with which I can publish my own books, without the cooperation of elite gatekeepers, explains why liberal democracy is destined to collapse.

Recall: He argues that right-wing populism is our natural political state—the human default. In his account, we sustained liberal democracy as long as we did because democratically-minded elites controlled the public square:

Partly, the diminution of elite cultural power is a practical matter of dismantling of the centralized technologies of mass communication that facilitated the elite control of the messages that circulated in the public sphere. … the internet, the computer and the smartphone have been developed in ways that give individuals both an increasing range of choices and a greater ability to express preferences in a very public way. Now an alienated, uneducated, working class ranch hand living in east Texas has access not only to the information disseminated by the major television channels or the national newspapers controlled by elites, but also to a myriad of smaller, more varied and less culturally sanctioned sources. Consequently, he or she is now able to choose which messages he or she wants to receive.

Similarly that ‘ordinary’ American, who once had very little political voice, is now able to broadcast his or her beliefs about events and policies, potentially as widely as any senior correspondent for the New York Times or Yale professor … With this democratization of the public sphere, elites have become less able to control the messages that are disseminated and therefore they are less able to assert the dominance of democratic views and to exclude anti-democratic alternatives …

Here’s where I begin to disagree. I agree with him that an ‘ordinary’ American now potentially has the power to broadcast his or her beliefs as widely as any senior correspondent for The New York Times.

But ‘potentially’ is lifting far more weight in his argument than it can support. Two senior correspondents for The New York Times, for example, can on a whim spend a full year chasing down rumors about Justice Kavanaugh’s Dick at Yale, find nothing worth reporting, make sleazy allusions in The New York Times about the Justice’s membre virile—apparently someone “pushed” it, once, during a drunken party, when an innocent lady was present—and in so doing so, hijack the attention of an entire superpower, for days, luring three serious Democratic candidates for the Presidency into saying they favor impeaching the Justice for the crime of having his penis pushed.

An alienated, uneducated, working class ranch hand may potentially be able to reach an audience just as large with his own political views, but it’s far more likely that if he tried something like this he’d be arrested. Some guy who wanders around Yale asking every woman whether they’d ever met the Supreme Court Justice’s Embajador would be seen as harasser, not a rival to The New York Times.

Yes, I can potentially broadcast my beliefs beliefs about events and policies—handily summarized in The Rise of the New Caesars and the Death of Freedom—as widely as any senior correspondent for the New York Times or Yale professor.

But probably this book will just sink off the horizon into the endless sea of noise.

How do I know this?

The elite gatekeepers

I was initially completely persuaded by self-publishing. I hated the elite publishing system—not because I’m a populist, but because it’s dumb and inefficient.

The old-fashioned system involves making your way through an obstacle course of elite gatekeepers:

You show your book to an agent. Agents are found by word-of-mouth, so if you have friends who discuss “agents,” you’ve already passed through a complex series of tricky elite gates. Elite Gate 1.

He or she agrees to represent you. Elite Gate 2.

Most of the time, your book is rejected. (“You will appreciate,” my agent once wrote to me, “that in this industry we take great pains to avoid saying, ‘the Little, Brown editor.’ Anyway, the Little, Brown editor passed.”) But if you get very lucky, a major publishing house buys it and you receive an advance. Elite Gate 3.

After buying it, the major publisher decides whether your book will be a success. Note: The publisher decides this, the reader does not. If the publisher is “behind” a book, they will purchase bookstore co-op; they will print lots of copies of the book and get them into bookstores; and they will send the book to high-profile reviewers in the mainstream media. Elite Gate 4, Dressage.

If and only ↔ they’re behind the book, they will send you off to talk about it on television and radio shows. Elite Gatekeepers 4 + n.

So you, the reader, don’t really decide which books to read. That’s an illusion. The publishers have already decided that for you. You buy the books they put in the window of the bookstore and at eye level. I know it feels as if you have free choice, but you don’t. We have the data to prove it.

For authors, the process is inscrutable and humiliating. Your book may be getting excellent reviews and selling well. But then, for some reason, the publisher decides it’s not a racehorse. After selling out the first few hundred copies, they cease printing any more and no one can find it in bookstores.

There’s not a thing you can do about it, because it’s the publisher’s property. They can do whatever they please with it.

This is why I was initially so excited about self-publishing. I thought it would be a huge improvement for writers. At last, I had the tools to bypass these lazy elite gatekeepers!

Q. Hold on, Claire, I’m confused. Aren’t you an elite?

A. Yes and no. I have elite credentials and elite class-consciousness. But it’s mostly false consciousness. I’m not a member of the part of the elite that shapes, has always shaped, and will always shape public opinion.

Q. Who’s side are you on?

A. Liberal democracy.

Q. That makes you an elite, right?

A. Not so fast. We’ll come back to this.

Self-publishing doesn’t work

It turns out that if you bypass the gatekeepers, no one reads your books. There are some exceptions. Some people are very successful with self-publishing. But they’re flukes. Flukes by definition are rare. And there’s almost no such thing as a successful, self-published book about politics. If you want to be successful in self-publishing, the way to go is genre fiction. (I don’t know why. )

But I didn’t know this, so I began eagerly self-publishing my books. It’s easy to do on Amazon. I self-published this book about India, my novella about Oxford, a companion guide to my book about Margaret Thatcher, and quite a few more—including my doctoral dissertation.

Despite my efforts to energetic efforts to publicize my work, no one bought them.

I tried buying Facebook ads targeting the demographic most likely to buy them. I can affirm that yes, Facebook knows everything about you, and they’ll gladly share the information with anyone who wants to purchase an ad. They know how old you are, your skin tone, your zip code, whether you suffer from erectile dysfunction, what time you wake up, your budget, how likely you are to click through the ads, how likely you are to complete your purchase after putting an item in the basket—everything.

I tried a number of demographics based on Facebook’s recommendations.

It didn’t work. No one bought anything.

I narrowed it down to people who had recently purchased very similar books. That didn’t work either.

I narrowed it down to people who had previously purchased my books.

Nope.

I tried lowering the price, to practically free.

Didn’t work.

I’m not exaggerating. People just don’t want to read self-published books.

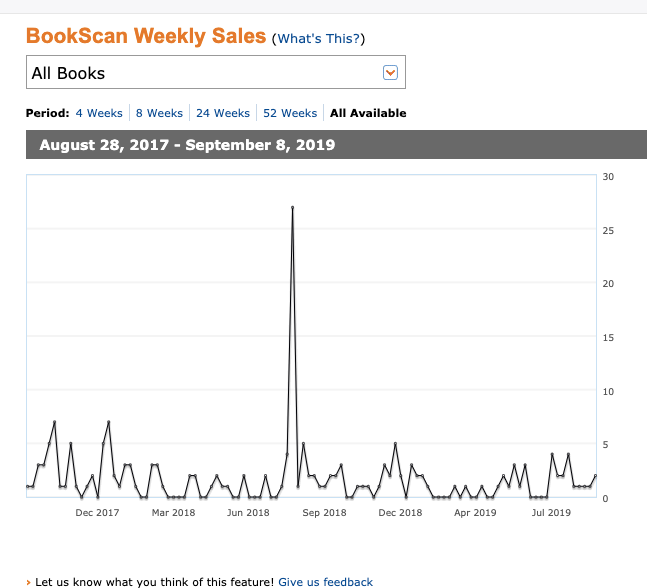

Below are books I published through houses like Random House and Basic.

Note: The high mark—27—does not represent 27,000 books, or even 2,700. I sold 27 books. Of these, 26 were copies of There is No Alternative: Why Margaret Thatcher Matters, and the other was a copy of Loose Lips.

The point, though, is that if you have written a book that you really want people to read, your only hope is selling it the old-fashioned way.

So why didn’t I do that this time? That’s another long story for another day.

But stay with me here, because this is germaine to the argument.

I will trick you into reading a book

So I assume that unless I try a different marketing strategy, this book, too, will disappear. That would be demoralizing. It would be far more demoralizing than the disappearance of other books I’ve published, because this one is more important. I actually believe what I’m saying. I believed what I was saying with my other books, too, but the point I was making wasn’t so important. Like Rosenberg—-although mainly for different reasons—I’m profoundly worried that we’re going to screw up liberal democracy.

I’ve done my best to explain why I think this, why this is happening, and what we should do about it in my book. But it will do no good unless people read it.

Then I noticed how many people signed up for this newsletter: about 2600. That’s many more than initially purchased any of my books. So it occurred to me, over the weekend, that this might be the solution. Newsletters are more suitable to modern attention spans. People like newsletters.

What this means is that soon—maybe when I have 10,000 subscribers—you’ll be reading my book. But you won’t realize it. It will seem to you just like the daily newsletter you’ve been enjoying. I’ll keep mixing it with thoughts from my Twitter feed and other commentary from the daily news. I won’t tell you which parts are from the book and which aren’t.

If you get really hooked on this newsletter, I may even be able to slip the whole book past you without you realizing, “It’s a book.”

After that, I’ll print hard copies and send them to the people who contributed to the campaign.

(Remember: Dickens used the same strategy with Great Expectations.)

The gatekeepers will always be with us

Contra Rosenberg, I don’t think our elites are more democratically-minded than the mass of our less-educated citizens aren’t. I think, to the contrary, that our elite is often more hostile toward liberal democracy than our citizenship at large.

But whatever the case, they’re still in place. I’m trying to do an end-run around them, but if I succeed, it won’t be because ordinary people have been empowered by new technology. It will be because I already have a foot firmly in the elite camp.

Moreover, it’s unlikely I will succeed. It is so unlikely that no one could reasonably conclude the triumph of non-elite views is “inevitable.”

If my experience is typical, and the data suggest it is, there is almost no chance that any given ‘ordinary American’ would be able to broadcast his or her views as widely as a senior correspondent of The New York Times.

If you give it any thought, you’ll see why.

Assume a state of perfect democracy, one in which each of the United States’ 327.2 million citizens has exactly the same ability to broadcast his or her opinions.

Initially, it would be chaos: no one can listen to 327.2 million political opinions at once.

But quickly, some people would become more influential than others. Even if the process was unregulated, it would not be random. If you’re on Twitter, think about how you choose the people you follow. You presumably follow them because you know them, like them, trust them, or think they’re a more valuable source of information than other people on Twitter. Voilà—you’ve selected an elite.

In any society larger than a village, there will be elite gatekeepers of public opinion. They’re a practical necessity. You rely upon them to filter out an enormous amount of irrelevant noise and help you to decide what to think. No one wants to listen to 327.2 million (usually stupid) opinions every day. No one has the time.

I share Rosenberg’s view that human nature is rotten, the outlook for liberal democracy grim, and the most likely replacement is right-wing populism. But I arrive at this conclusion by means of a very different argument.

Why does it matter, Claire? If you wind up in the same place, who cares if you get there by a Mercedes or a pogo stick?

Let me answer with an analogy. Let’s say Rosenberg and I are the attending physicians in a poorly-equipped emergency room in an impoverished and irrelevant country.

“The patient presents with fever, muscle pains, and a sore throat,” says Rosenberg, glancing at the patient’s chart.

“Yep, he sure does,” I agree.

“And oh, look—now he’s vomiting.”

“Yep.”

“Look at that disgusting skin rash,” he says.

“Oh, yeah. That’s disgusting.” He jots down the words, “disgusting skin rash.”

We’re in perfect agreement about the symptoms. We agree this patient has cold, clammy skin. We agree about his weak pulse.

Then the patient faints. We even agree that he’s not conscious.

“His life is at risk,” says Rosenberg.

“Definitely,” I agree.

“Gone by the morning, I reckon,” Rosenberg adds.

“Yep.”

We are as one about the symptoms, the danger, and the probable outcome.

“Ebola,” Rosenberg concludes. “Poor blighter got it from eating bushmeat.”

I shake my head. “No, no. A peanut allergy. We could save him if we had a shot of epinephrine. But we ran out after Brexit. So he’ll die.”

Claire, what about Trump? He’s definitely not the elite’s choice, right?

I’m afraid he is, folks. He styles himself as a populist, but like every other well-known politician, he serves at the pleasure of the elite gatekeepers.

The elites at NBC gave him a platform on The Apprentice. The elites made him a public figure. Everything you know about him, probably, you know from established, mainstream media gatekeepers.

And no, Fox News is not the voice of an alienated, uneducated, working class ranch hand living in east Texas. For the love of God.

Please do not write to me telling me you’re insulted on behalf of alienated, uneducated, working-class ranch hands. If you’ve read this far, you are not a member of the alienated, uneducated, working class. Insisting that you’re a simple, uneducated, working-class ranch hand when clearly you are not is the right-wing populist version of radical chic. Our working class is busy working, not reading this newsletter.

You know how you can tell that Fox isn’t the voice of Chuck, the alienated, uneducated, working class ranch hand living in east Texas? Like this. Do you read things like this about Chuck?

Chuck agreed in June to break off his slower-growing publishing assets from his television and film businesses after coming under pressure from shareholders. Rupert Murdoch, Chuck’s billionaire founder, will remain Chuck’s CEO, with Chase Carey serving as chief operating officer and James Murdoch working as Carey’s deputy.)

No, folks, the elites are still firmly in control of the media. The media has been nowhere near as democratized as Rosenberg reports.

So the spectacle we see before us does not represent a true democratic uprising—nor would we want such a thing, because it always ends in some kind of authoritarianism.

No, this grotesquerie represents a savage intra-elite power war between two elite camps that have both lost their marbles and all sense of responsibility.

They comprise what Rosenberg calls the “cultural elite.”

… These include political institutions like the Congress, the courts and the law, state and city administrations, and the police, and economic institutions like banks and corporations. Via these institutions and the rewards and punishments that are administered by them, elites can manage citizen action so that it approximates, even if inadequately, democratic practices. Elites also exercise ‘democratic control’ by managing the discourses that dominate the public sphere. They can thus affect the pool of socially approved knowledges and preferences that are available to individuals draw upon as they seek to understand, evaluate and react to the circumstances of daily life. This cultural domination is secured through the control of the means by which these discourses are dispersed. This includes the mass media and the institutions of socialization, such as schools and universities. Through these vehicles, the elite can disseminate the orienting beliefs and values of democratic culture.

We could also call it, “The Swamp.” It is cleaved in two—almost perfect mirror images—and they are both energetically disseminating “the orienting beliefs and values” of populism—left-populist and right-populist—rather than the values of liberal democracy.

I agree with Rosenberg that in any such a contest, right-populism will win.

So I end up in the same place as he does, but get there by a different road.

This isn’t the only problem with Rosenberg’s argument. He has confused, or left undefined, important concepts. Specifically, he uses “liberal democracy” an umbrella term that covers concepts that are at odds with democracy, such as freedom, decency, and justice.

This is a mistake to which our generation, for reasons I detail in my book, is particularly prone. (I assume Rosenberg is about my age, which means he received something like the same education I did, which means he’s apt readily to conflate these concepts.)

But I agree with him that right-wing populism is no trivial affliction. As he writes,

Right wing populism is sometimes considered a point further to the right of conservatism and thus its ideological cousin. This view has been expressed both by some political scientists studying contemporary right wing parties (e.g. Dunn, 2015) and by advocates who have attempted to legitimate their cause to a conservative audience attract (e.g. Bokhari and Yiannopoulos, 2016). In my view, this is misleading. The intellectual roots and underlying logic of right-wing populism are better understood as a contemporary expression of the fascist ideologies of the early 20th century, one that reflects the dominance of the democratic environment in which it is currently emerging.

(“Yiannopoulos, 2016?” Isn’t that cute?)

I agree, though, and I discuss this at much greater length in my book.

So far so good. But his prognosis then becomes muddled. He does not say that given its intellectual roots and logic, right-wing populism will inevitably bloom as full-blown fascism. But it’s implied by what he writes, and he doesn’t explicitly say anything to the contrary.

I’m not persuaded this is so—and even if it is so, I’m not sure it’s a wise argument to make.

First, despite the fascist intellectual roots and underlying logic of right-wing populism, the “dominance of the democratic environment,” as he puts it, makes this ideology a different thing in power, in both form and function. It takes a different shape.

Second, one reason we need to clearly disambiguate right-wing populism and early-20th century fascism is that if you insist, or intimate, that right-wing populism and fascism are the same thing, you won’t be taken seriously, nor should you be—because this equivalence grossly minimizes the enormity of the early-20th century fascists’ crimes.

If Rosenberg will insist to the American people, with a straight face, that they are now living under a fascist government, it won’t serve as the salutary warning he intends. To the contrary. It will cause them to conclude the horrors of fascism have been overstated.

Contemporary right-wing populist governments may come to resemble the fascist regimes of the early 20th century—I fear they will—but most of them have not yet.

The Inevitability

When Rosenberg concludes that right-wing populism is inevitable, what precisely does he mean? I can envision a range of scenarios along a continuum, from

Right-wing populists will be elected, but they will be stymied at every turn by mature democratic institutions and thus limited in the amount of damage they do.

Indeed, in some cases, citizens will tire of their incompetence and vote them out of office before they consolidate power so fully that they can no longer be ejected by normal democratic mechanisms—making this a passing phase;

to

Every liberal democracy will experience full-grown fascism—and, inevitably, total war, because that is the inevitable fascist terminus. In the nuclear era, none of us will survive.

Although he believes right-wing populism inevitable, he does not explicitly say which scenario he believes to be inevitable, nor which point of the continuum seems to him more probable. He does not say, in effect, whether he thinks this would be merely grim or literally the end of the world.

I don’t know, either. But I would caution against predicting “10” in the hopes of achieving “1.” It’s intellectually dishonest, and probably counterproductive.

I don’t know if Rosenberg believes the Trump Administration is a proto-fascist government. But if he truly believed that, he wouldn’t say or write what he does. Fascist governments tolerate no dissent. If full-blown fascism is inevitable, it’s insane to stake out ground as a dissenter. You’ll be first on the list when it comes time to round up the intellectuals and shoot them.

So I don’t believe he thinks full-blown fascism is inevitable. I believe he thinks it’s possible—as do I—and he is writing this as a warning. By showing us we are on a dangerous path, he hopes, he will persuade us not to take it.

But his warning isn’t as convincing as I’d like it to be. There are too many diagnostic mistakes. And he concludes with advice that makes no sense. So I think my book will do a better job, if I can convince people to read it.

For example. What is his advice? How might we change our destiny?

.. we can ask if this trajectory and the promised results [right-wing populism] are inevitable. I think the answer is probably yes. However there is another possibility, if an unlikely one. Before it is too late, the democracies might directly address their own critical vulnerability, the inadequacy of their citizens. … The alternative is to create the citizenry that has the cognitive and emotional capacities democracy requires. This would entail a massive educational initiative, one that would have to be premised on the recognizing the dramatic failure of prior efforts. Perhaps in this way, democratic forms of governance may yet prevail.

But this is nonsensical—as surely he must know—because his very argument, to this point, has been that human nature makes democratic governance impossible, that human nature cannot be changed, and what’s more, science has revealed that this is human nature. Everything is written. Our liberal commitment to Anglo-American political theory—or watching too much Lawrence of Arabia when we were kids— prevents us from courageously facing this.

For decades, the work on social cognition regarded the conception of the individual as a reflective, integrative, self-directing agent as a straw man, one that was contradicted by a large and ever-growing body of evidence. The result is a view of people a inherently fast and sub-rational (as opposed to slow and considered) thinkers who are heuristic, schema and emotionally driven processors of information. How they think and react is thus not circumstantial and readily remedied, but is instead indicative of who people really are. This is human nature [my emphasis] and therefore something which is certainly not easily, and perhaps not even possibly, changed.

If this is true, we can’t re-educate our citizens. (Also: “re-education” sounds like a cure worse than the disease. He didn’t use the word “re-education,” but if previous educational efforts have failed, re-education is implied.)

But I don’t think he’s got the nature of the problem right. We’ve managed until very recently to govern ourselves—despite our highly limited human nature—without descending into fascism. It is not true, I would argue, that our elites have lost control of public discourse.

The great danger of Trump, in my view, is not Trump per se. I don’t think he will fundamentally transform America. The institutional safeguards that have always made it difficult for any one man to impose a fascist government on the United States will continue to make it difficult.

My fear is that our entire elite class is so distracted by their inter-elite struggle that they’re paying no attention to the rest of the world—which is vulnerable to fascism.

I fear that while our elite is distracted, the rest of the world will go to hell, and they will realize this only when it’s too late.

I fear that we should be thinking about this:

But instead, our elites are completely preoccupied by reports and sightings of Kavenaugh’s dick.