Are you new to the Cosmopolitan Globalist? Welcome. Here’s the first part of this essay:

And these interviews with Hungarians are short, but they’re very well done:

The United States of Europe

At the dawn of the twentieth century, a dozen distinct ethnic groups lived under the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, speaking at least sixteen languages. Germans and Hungarians, together, made up 44 percent of its peoples, and power was concentrated in their hands.

After the 1867 compromise, ethnic Hungarians intensified an often repressive campaign of Magyarization, causing bitter resentment. By 1906, the tempo of nationalist uprisings and terrorism in the Austro-Hungarian empire was quickening. The Archduke Franz Ferdinand was uneasily aware that two ethnic groups could not forever dominate the others.

So alarmed was he that he entertained a radical solution: reconstituting the Austro-Hungarian empire as a supranational, federal structure composed of sixteen national states, all under a constitutional monarchy. The circle of scholars in his entourage, foremost among them Aurel Popovici, sketched out detailed plans for such a polity. Popovici, greatly inspired by the Constitution of the United States, called the hypothetical federation, “The United States of Greater Austria.” He might also have called it “the European Union,” for the plan was in its essentials the same.

At the end of his book elucidating the idea, Popovici wrote,

The moment is a historical and a decisive one. For our whole future: will the Habsburg Empire preserve or will it collapse? Everything can still be aligned, everything can still be saved. It’s now or never!

Franz Ferdinand was serious about this plan. It would not have been easy to implement, not least because Hungarians had no intention of losing their dominant position. But it could have worked. We know this because it has.

It’s deeply mournful to imagine the other twentieth century that might have been. Had only the Archduke taken Popovici’s imprecation to heart: Now or never. But the Archduke hesitated, and on June 28, 1914, met his fate.

The ghastly twentieth century had begun.

And the war came

“My darling one and beautiful, everything tends towards catastrophe and collapse,” wrote the British naval official Winston Churchill to his wife. It was midnight on July 29. One day before—a month to the day after the Archduke’s assassination in Sarajevo by a Serbian nationalist—Austria-Hungary had declared war on Serbia. Catastrophe came, and by its end, the German, Ottoman, and Austro-Hungarian empires had collapsed.

The United States entered the war against Austria-Hungary in December 1917, eight months after declaring war on Germany. Among American war aims were ending forever the militarism of Austria-Hungary and reordering Europe along the principles of Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points.3 Although the term “self-determination of peoples” is not mentioned in the Fourteen Points, it was assumed.

In Padua on November 3, 1918, the representatives of the Italian High Command, representing the Allies, signed an armistice with their Austro-Hungarian counterparts, who represented a rapidly disintegrating army and a collapsing empire.

That year, the crops failed and the pandemic began. Hungarians had nothing but death, defeat, and grinding misery to show for the war. Currents of nationalism became torrents. Tension escalated among ethnic groups. Their demands for independence grew implacable, and soon, unstoppable.

When the empire collapsed, it did so with breathtaking speed. In October 1918, the Hungarian parliament voted to dissolve its union with Austria. By the end of October, the Habsburg realm was gone.

The Bolshevik Revolution and the Hungary-Romania War

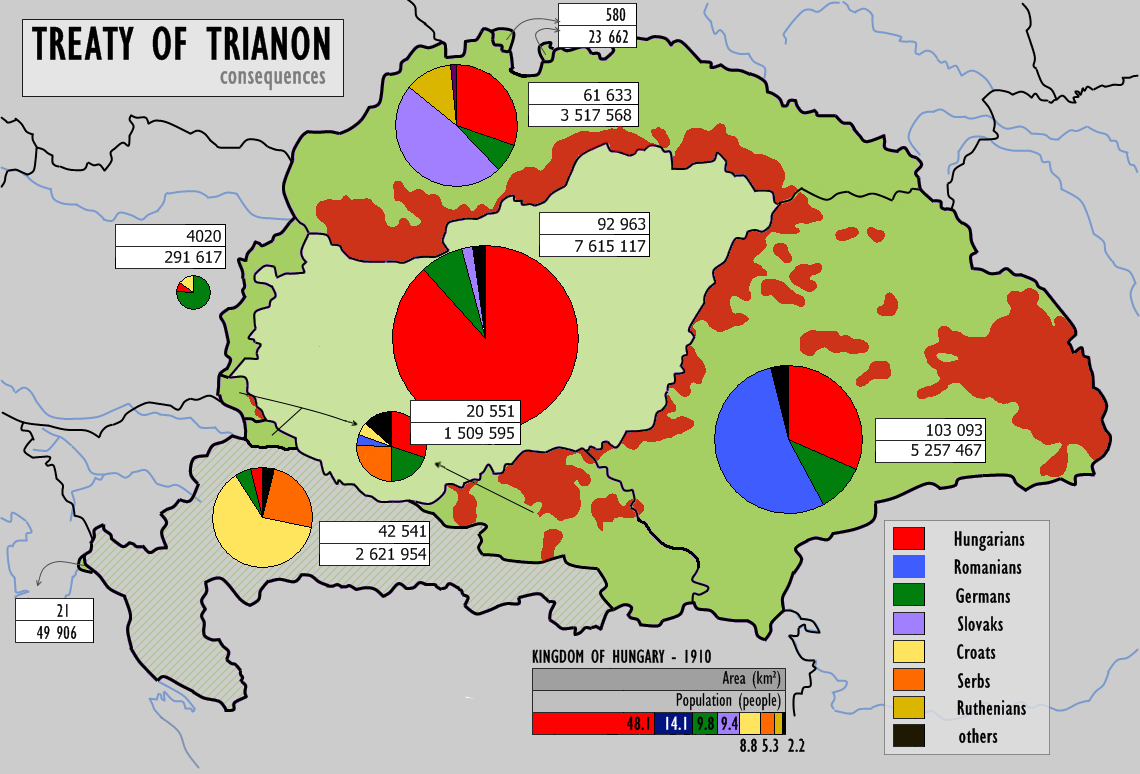

Hungary declared itself a republic on November 16, 1918. But so did the other territories of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and they all laid claim to the same territory. Only 54 percent of the Hungarian Kingdom was ethnically Magyar. In many regions, ethnic Hungarians were a minority. Throughout the next year, Hungary would fight viciously with its neighbors over the ruins of the empire.

When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions. Hungarians had been defeated in the most bitter and bloody war in human memory. Still under an economic blockade, the new republic suffered from skyrocketing inflation, mass unemployment, and shortages of housing, food and coal. In November, the Bolshevik revolutionary Béla Kun returned from Moscow. He modeled his tactics for agitating against the government of the new republic on Lenin’s, denouncing and promising everything to everyone. In March, under direct orders from the Kremlin, he staged a successful coup d’état. The first Soviet republic outside of Russia was pronounced in Budapest.

The Hungarian Soviet Republic endured for 133 days and came complete with a Red Terror. Several hundred people, mostly scientists and intellectuals, were murdered. Kun swiftly nationalized private property, and despite his initial promise to redistribute the land to the peasants, began converting it to collective farms. The Lenin Boys, a communist paramilitary, confiscated the peasants’ food for redistribution in the cities. The Lenin Boys did what Lenin Boys do: They hunted down the bourgeoisie and the counter-revolutionaries, robbed everyone blind, and undertook a brisk schedule of shootings and hangings. These measures were received as warmly as they usually are.

Kun stupidly declared war on Romania. The Entente had been willing to make territorial compromises, but Kun rejected their overtures. “Comrades,” he declared at a rally,

we do not profess the doctrine of territorial integrity, but we want to live, and this is why we did not accept that our freed proletarian brothers living in the neutralized zone be rejected under the yoke of capitalism. … It is a matter, therefore, which concerns the struggle between the international revolution and the international counter-revolution.

The Allies supported Hungary’s neighbors, and France in particular supported Romania, to whom it owed a debt for the contribution of the Romanian Army to the victory of the Entente. When the war came to a close in 1919, there was little of Hungary left.

Kun had imagined that the Red Army would intervene to settle the war on Hungary’s terms, but the Red Army’s setbacks in Ukraine ensured that this was not to be. The industrial proletariat meanwhile decided it had better things to do than fight the Romanians on behalf of a Bolshevik lunatic, so the Romanians wound up marching into Budapest. Kun fled to Austria, blaming the Hungarians: “The Hungarian proletariat betrayed not their leaders but itself,” he said:

If there had been in Hungary a proletariat with the consciousness of the dictatorship of the proletariat it would not collapse in this way … I would have liked to see the proletariat fighting on the barricades declaring that it would rather die than give up power. … The proletariat which continued to shout in factories, ‘Down with the dictatorship of the proletariat’, will be even less satisfied with any future government

Kun later perished in Stalin’s purges.

Trianon

In the same year, leaders of the Allied powers—Britain, France, Italy, and the United States—assembled in Paris to redraw the world map. Few modern conflicts do not, in some way, have their roots in the Paris Peace Conference.

The Treaty of Versailles was, strictly speaking, only one of the five treaties issuing from the conference; it was imposed upon the Weimar Republic. The term Versailles often (incorrectly) serves as shorthand for all five, including the Treaties of Saint Germain, Neuilly, Sèvres, and Trianon. Whatever we call them, no treaties in history have been more comprehensively impugned. They are the treaties historians love to hate.

And for good reason. The peacemakers knew little about the religions, ethnic loyalties, and national aspirations of the people whose fates they determined. The borders that emerged from the ashes of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires were not those of natural nation-states; they were contrivances to secure the great powers’ control over their colonial possessions and create buffer zones between themselves and their enemies.

The boundaries of the new countries made no sense.4 They yoked together people who loathed each other and had always loathed each other. They separated people who spoke the same language and had lived together for centuries

In June of 1920, the peacemakers gathered in the Grand Trianon château in Versailles to sign the Treaty of Trianon, which formally ended the war between the Allies and the Kingdom of Hungary.5 France was allied with Hungary’s rivals in the ongoing Hungarian-Romanian war, an arrangement that would be formalized in the so-called Little Entente, aimed at preventing a Habsburg restoration. French diplomats played the largest role in writing the treaty. The Allies did not negotiate the treaty. They had won. Hungarians had no choice but to accept.

In theory, the treaties of the Peace Conference were meant to grant self-determination to the peoples, vast in number, who had for centuries lived under the multiethnic Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman Empires. The peacemakers made an attempt to apply this principle to the Balkans and Central Europe, but soon realized that homogeneous nation-states could never be created from such a map, no matter how they carved it, for every state would have a sizable ethnic minority within its borders. They endeavored to draw the lines so that most ethnic Germans would live Austria, Magyars in Hungary, Poles in Poland, Italians in Italy, and Romanians in Romania. As for everyone else? They’d go to Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia. Good enough for government work.6

“As a Europhilic American, I don’t want European countries to be like America; I want them to be European, and more to the point, I want France to be French, Hungary to be Hungarian, Sweden to be Swedish, and so forth.”

—Rod Dreher (Good luck with that, Rod!)

Hungary’s borders, they concluded, should be, more or less, those to which the Kingdom of Hungary had been reduced after the war. This left the new Hungary a landlocked dwarf. The Treaty of Trianon was the most punitive of the treaties imposed in the postwar settlement. Hungary lost nearly three-quarters of its prewar territory and nearly as much of its population.

Large regions of the Kingdom were assigned to neighboring countries on ethnic grounds. But these regions had very large Hungarian minorities. Suddenly, 3.4 million ethnic Hungarians—nearly a third of the ten million ethnic Hungarians still alive after the war—found themselves formally separated from their ethnic kin. Worse, before the war they had been not just the majority, but the aristocracy: Magyars had been the landowners in the Hungarian Kingdom, and they viewed the other ethnic groups as peasants, because they were. Now they were ruled by peasants.

There was no love lost between Magyars and other ethnic groups. The former had for years attempted to Magyarize the latter. The Allied decision to break up the Kingdom so punitively was at least partly motivated by sympathy for those ethnicities, who had regaled them with stories of their repression at Magyar hands. Magyars were not destined to become beloved minorities in the new homes to which they had been assigned.

Nor were they even to be left alone in their new, amputated Hungary. They would still be obliged to live with a large minority of Germans, Slovaks, Croatians, Romanians, Bunjevacs, Šokacs, Serbs, Slovenes, Jews, and more, just as before—except that they would no longer be annealed politically by their shared loyalty to the Dual Monarchy. These other groups would now be aliens in the Hungarian nation-state—which was supposed to be, according to the theory, a polity legitimized by the shared ethnicity of its citizens.

Hungarians were outraged by the settlement. Hungary had lost its Hungarians, its territory, half of its ten largest cities, its access to the sea, half of its arable land, its industrial base, its raw materials, and its markets. The treaty limited the Hungarian army to 35,000 officers and men and abolished the Austro-Hungarian Navy. It also obliged Hungary to pay reparations—to their hated peasant neighbors.7

The Hungarian delegation signed the treaty under protest. Agitation for its revision began immediately. It has never ceased. The anti-Trianon slogan “Nem, nem soha!” (“No, no never!”) became ubiquitous.

Hungary, lamented Hungarian nationalists, had been maimed.

They should have thought of that before starting the war.

Admiral Horthy

Now we arrive at the part that is most relevant to explaining what Viktor Orbán is doing, and why it’s so sinister.8

The Bolsheviks were ousted by Conservative Royalists, the so-called Whites, led by Miklós Horthy, the former commander in chief of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. The march of the Whites came complete with a White Terror, even longer and bloodier than the Red. For two years, militias tortured and executed leftists and Jews, whom they blamed for Hungary’s territorial losses and the rise of the Bolshevik regime.

Horthy marched into Budapest on November 16, 1919. The Hungarian Parliament elected him regent of a new Kingdom of Hungary, albeit one without a king, since Charles IV had been exiled and the Allies wouldn’t let him to return. Horthy demanded the expansion of the regent’s powers: He wanted the prerogatives of the king, including the right to appoint and dismiss prime ministers, convene and dissolve parliament, and command the armed forces. The Parliament granted him this wish.

This is how the Hungarian historian, István Deák, describes Hungary under Horthy:

Between 1919 and 1944 Hungary was a rightist country. Forged out of a counter-revolutionary heritage, its governments advocated a “nationalist Christian” policy; they extolled heroism, faith, and unity; they despised the French Revolution, and they spurned the liberal and socialist ideologies of the nineteenth century. The governments saw Hungary as a bulwark against Bolshevism and Bolshevism’s instruments: socialism, cosmopolitanism, and Freemasonry. They perpetrated the rule of a small clique of aristocrats, civil servants, and army officers, and surrounded with adulation by the head of the state, the counterrevolutionary Admiral Horthy.

Does this sound familiar?

The Horthy government is sometimes described as fascist, but it’s not the mot juste; the regime had a parliament, and it was possible to express critical views in a handful of opposition papers. But it collaborated with the fascists and had fascist ministers. Fascist movement such as the Arrow Cross emerged, but Horthy was somewhat hostile to them (much as Orbán has been somewhat hostile to Jobbik.)9

If he was not a fascist, however, Horthy certainly wasn’t a liberal democrat.

Or a hero.

Under Horthy’s first prime minister, István Bethlen, a certain measure of stability returned. British economic support played a significant role in Hungary’s stabilization.

But then came the economic crisis. In 1932, Horthy replaced Bethlen with Gyula Gömbös, an outspoken antisemite and, yes, a fascist. Gömbös reoriented Hungarian policy toward Germany and Italy, and undertook the project of Magyarizing Hungary’s remaining minorities. He signed a trade agreement with Germany that helped Hungary’s economy, but made Hungary dependent on the Third Reich for raw materials and markets.

To recidivist Hungarians sorrowing for their lost territories, Hitler was an electrifying figure. Antisemitism became the ideological lodestar of the Horthy system. The Arrow Cross embraced Nazism enthusiastically.

Horthy’s government passed the First Jewish Law in 1938. Despite its name, it was not, in fact, the first such law. Upon taking power in 1920—many years before the rise of the National Socialists in Germany—Horthy’s government passed the Numerus Clausus Act, the first antisemitic law in twentieth-century Europe. The First Jewish law of 1938, which restricted the number of Jews in the professions, the government, and commerce, was the most antisemitic law outside of Nazi Germany. The Second Jewish Law, passed the following year, squeezed Jews even more. Some quarter of a million Hungarian Jews lost their jobs.

Hungary at this time declared an official policy of forced Jewish emigration. When Hungarian Prime Minister Pál Teleki met Hitler in November 1940, it was Teleki, not Hitler, who insisted upon the necessity of expelling every Jews from Europe. However, in a 1940 letter addressed to his prime minister, Horthy explained that he couldn’t yet completely eradicate every trace of Jewry from Hungary’s economic life:

As regards the Jewish problem, I have been an anti-Semite throughout my life. I have never had contact with Jews. I have considered it intolerable that here in Hungary everything, every factory, bank, large fortune, business, theater, press, commerce, etc. should be in Jewish hands, and that the Jew should be the image reflected of Hungary, especially abroad.

But it was impossible to expel them all immediately, he explained, because the Hungarian economy would grind to a halt without them:

Since, however, one of the most important tasks of the government is to raise the standard of living, i.e., we have to acquire wealth, it is impossible, in a year or two, to replace the Jews … for we should become bankrupt.

The Third Jewish law, passed in 1941, defined anyone with Jewish grandparents as “racially Jewish” and prohibited Jews from marrying non-Jews. Jews who had sexual relations with a “decent non-Jewish woman resident in Hungary” would be imprisoned.

Between 1938 and early 1944, the Hungarian parliament passed 22 antisemitic laws and issued 267 antisemitic ministerial and governmental decrees. These targeted Jewish land for confiscation, deprived Jews of the right to vote, excluded Jews from military service, and forced them instead to perform unarmed military labor—into slavery, in other words. Local authorities, in an access of zeal, often exceeded the letter of these laws, taking it upon themselves to ban Jews from spas and markets.

After the Anschluss, Hungary threw in its lot with the Nazis and joined Hitler in dismembering Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Yugoslavia. It succeeded in reclaiming parts of the lost territories. In June 1941, Hungary joined Germany in invading the Soviet Union.

In August, Horthy’s government ordered the deportation of some 20,000 Jews without Hungarian citizenship, almost all of them refugees from Nazis, to the city of Kamianets-Podilskyi in Ukraine. They were sent in the full knowledge of the fate awaiting them, and slaughtered by Einsatzgruppen commandos. The next year, the Hungarian military and gendarmerie murdered 700 Jews in Újvidék. Some 45,000 Jews conscripted into forced labor battalions died of exposure, enemy fire, or mass executions on the Eastern Front.

“Although the [military] Labor Service System was not established as a vehicle of murder,” writes Robert Rozett, a scholar of the Hungarian Holocaust,

it became one, primarily because of the treatment of the men on the front. Their difficult labor was routinely augmented by brutal and humiliating harassment—most infamously, being made to pull wagons in place of perfectly healthy horses. In a great many instances the Hungarian soldiers responsible for the Jewish men stole their food, and resold small portions of it to them for exorbitant prices. Suffering from hunger, disease, exposure to the elements and cruel treatment, many men died. Some were killed after being assigned deadly tasks; the most gruesome was to clear minefields with only sticks, and without any previous training. Others were murdered outright. Some 400 Labor Service men, sick with typhus, were burned alive in a barn near the Kolkhoz of Doroschitz.

Over the course of the war, Horthy began to have doubts about Hitler. He was greatly demoralized when in 1943, the Soviet army punched through Romanian troops at the River Don and obliterated the Second Hungarian Army. Hitler blamed Hungary’s Jews—they had died in large numbers in the defeat—and demanded Horthy punish them. Horthy obliged by supplying him with 10,000 more Jews for forced labor battalions.

As it became obvious that the Axis would lose the war, and with the Red Army on Hungary’s borders, Horthy sought a separate peace with the Allies. The news reached Hitler. Enraged, Hitler summoned Horthy to a conference in Salzburg. To placate him, Horthy agreed to deport 100,000 more Jews. In the revisionist storyline, Horthy declares he will send no more than that and becomes a hero—the leader who saved as many Jews as he could. In reality, Horthy decided to send their families, too.

Horthy’s role in the destruction of European Jewry is crystal clear. It was unambiguously documented. By the spring of 1944, everyone knew what transporting Jews into German hands meant. Rozett puts it this way:

The Germans pushed for concerted action against Hungarian Jewry, and Horthy not only did not resist—he put the government apparatus at their disposal. The well-oiled process of destruction of the Jews followed quickly: restrictions, wearing the Jewish badge, confiscations, the establishment of ghettos and systematic deportations.

Horthy’s dishonor gained him nothing, because the Salzburg conference was a ruse: Hitler had decided to invade Hungary. German troops entered Hungary in March 1944. Hitler left Horthy in office as a figurehead. Adolf Eichmann rushed to Hungary to personally supervise the deportation of Budapest’s Jews. The deportation began on May 14, 1944 and continued at a rate of 12–14,000 a day until July 24, by which date 437,000 Jews had been deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and gassed upon their arrival, save for those selected for medical experiments and delivered to Dr. Mengele.

Eichmann’s Kommando numbered only twenty men. It was left to the Hungarian Interior Ministry, the Gendarmes and local authorities to carry out the deportations. Eichmann was pleasantly surprised by their enthusiasm for the job. As a result of their initiative, Hungarian Jews were, in the words of the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, “identified, plundered, ghettoized, deported, and murdered with a speed and efficiency virtually unparalleled in the history of the Holocaust.” During this time, the gas chambers in Auschwitz set a record, killing 800 children in a single day.

In America, given our history, to protest against “race mixing” has a clear and unambiguously ugly meaning, one that decent people must reject. It is unfair, though, to apply the American framework to Europe, which has a very different history.

—Rod Dreher, defending Orbán from the charge that his protest against “race mixing” was racist.

The Allies were by this time also well aware of the fate of the deported. The Pope, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and King Gustaf V of Sweden pleaded with Horthy to use his influence to stop the deportations. Roosevelt threatened military retaliation unless they were ceased, warning Horthy he would be prosecuted for war crimes. Horthy complied. The deportations ended on July 9.

On October 15, Horthy announced in a national radio broadcast that Germany had lost the war, and Hungary had concluded a preliminary armistice with the Soviet Union. Hitler responded by sending a Waffen-SS commando to kidnap Horthy’s son and then detain Horthy, who was given to understand that he would withdraw the armistice or his son—by now, at the Mauthausen concentration camp—would be killed. Horthy complied. As the Nazis demanded, he abdicated his office and named the leader of the Arrow Cross as the new head of state and prime minister.

The Arrow Cross swiftly prevented the surrender that Horthy had arranged, even though Soviet troops were now deep inside the country, and returned to their most urgent priority—killing Jews. Between November 1944 and January 1945, Arrow Cross death squads shot some 15,000 Jews on the banks of the Danube. They continued until Soviet forces took Buda and Pest in early 1945. “This was not a marginal group of fanatics,” Rozett emphasizes, “but part of the Hungarian mainstream.” They killed or deported 100,000 Jews before Soviet troops took control of the country in 1945.

After the war, Hungary’s Trianon borders were restored, except for three Hungarian villages, which were transferred to Czechoslovakia.

Of the 14.5 million people living in Hungary at the beginning of the war, 825,000 were Jews. They had been law-abiding, patriotic, prosperous, educated, and completely assimilated. They trusted the rule of Hungarian law. They were loyal Hungarians and proud of it. Nearly 600,000 of them perished in the Holocaust.

In December of 1945, Horthy was released from Nuremberg. He could not return to Hungary, which was now a Soviet satellite. He died in exile in Portugal, a year after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, disconsolate that the revolution had failed.

The return of the repressed

There is much more one could say about Hungarian history. For economy’s sake, I have written nothing about 1956, or 1989. But this is enough to place Orbán in context.

You may have known some of this. You may have known none of it. But this I guarantee: Viktor Orbán knows all of it. So when Orbán praises Horthy, speaks like Horthy, and behaves like Horthy—when he uses Horthy’s rhetoric and cloaks himself in Horthy’s symbols—it’s not a mistake.

Rule number one: Rewrite history, deliberately fostering nostalgia for an authoritarian past. (If the lessons of history suggest the path you’re following leads to disaster, then history, not the path, must be changed.)

Rod Dreher, presumably, doesn’t get the Horthy references. Tucker Carlson sure doesn’t, and neither do the Republican Senators who (God help us) decided, after watching Tucker Carlson broadcast from Budapest, they were very impressed with this family-friendly Orbán fellow and cut off a US program to aid Hungarian journalists. That Donald Trump didn’t get the references is a given, though one doubts he would have been disturbed even if he had. He brought an end to the State Department’s policy of giving Orbán the cold shoulder, and welcomed him to the White House.

Today’s news:

Hungary blocks €18 billion in aid for Kyiv and deepens rift with EU.

Finnish parliament to hold NATO vote while awaiting Hungary, Turkey decisions

Revisionist history

If you tell them that Orbán’s government has built statues and memorials to Horthy, has renamed Hungarian streets after Horthy, that plaques and town squares and monuments dedicated to Horthy have under Orbán sprung up like mushrooms after a spring rain, most Americans would shrug. Just as Hungarians could not be expected to grasp what it meant to Americans to see the Confederate flag raised in the Capitol on January 6, Americans can’t be expected to grasp what Horthy means in Hungary. If CPAC delegates know the name “Horthy” at all, which I doubt, it would hardly evoke much emotion. Nor would their innocence have been rectified had they read such publications as The Economist, which in 2012 asked brightly, “Does Hungary have a new hero?”

Miklos Horthy, Hungary’s wartime leader, whose birthday is today, is enjoying a controversial renaissance. This weekend the mayor of Csókakő, a picturesque village west of Budapest, inaugurated a bust of the admiral, flanked by far-right supporters in military-style uniforms. The Csókakő memorial is the latest of a wave of Horthy memorials. The town square in Gyömrő, has been renamed for him. Horthy’s Alma Mater, the Reform College of Debrecen, in eastern Hungary, has put up a plaque to its former pupil.

The Economist then tells us that Horthy brought “peace, stability and steady economic growth after the trauma of the Treaty of Trianon.” Hungary, they add “remained a quasi-democracy for most of his rule and a relatively safe haven for its Jewish community.” (My God, that is impressively stupid. I suppose, technically, it’s true; a fall from a skyscraper is “relatively safe” until the last two inches, after all. This is why you need to subscribe to the Cosmopolitan Globalist if you haven’t already.)10

In this new, revisionist dispensation—by which even The Economist is impressed, it seems—Hungary was not a collaborator in the Holocaust, but the helpless victim of Nazi aggression. Germans, not Hungarians, killed the Jews. Horthy tried to protect the Jews of Budapest.

Fidesz has rewritten the constitution to suggest that the Horthy government wasn’t responsible for Hungary’s actions during the last fourteen months of World War II, when the majority of Hungarian Jews were deported and murdered. The crimes of Hungarian fascists have been erased from national museums. The national museum now hosts exhibits glorifying Horthy. Fidesz funds an entire think tank dedicated to Horthy revisionism.

In 2017, inaugurating a newly renovated luxury house once owned by Horthy’s minister of Education, Kuno Klebelsberg, Orbán declared,

That the lost World War, the 133 days of Red Terror, the Treaty of Trianon did not crush us underneath the foot of history, well, this is thanks to a handful of exceptional statesmen: Governor Miklós Horthy, Prime Minister István Bethlen, and Minister Kuno Klebelsberg.

Klebelsberg was a Magyar supremacist and ravening antisemite who blamed Hungarian Jewry for the bourgeois liberal and communist revolutions as well as the Treaty of Trianon. A day later, János Lázár, Minister of the Prime Minister’s Office, called Horthy a “great Hungarian patriot.”

This nostalgia has not gone unnoticed by Hungary’s neighbors—and how could it? Within days of winning the 2010 election, Orbán announced June 4 would henceforth be a day of national mourning for the “Trianon diktat.” In 2011, Hungary took over the revolving presidency of the EU. In the atrium of the very building where officials from the 27-member EU hold their summits, Hungarian officials installed a giant carpet featuring a map of Hungary. Guess where the borders were.11 That was the month in which the government passed its new citizenship law, granting ethnic Hungarians everywhere the right to a Hungarian passport. Soon they would have the right to vote, too. This created at least a million new Hungarian citizens. And Orbán just won’t knock in off with that map: He posts it on social media whenever he gets the chance. Every time, it infuriates Hungary’s neighbors. You do it once, maybe—just trolling. Regularly? Despite the ill-will it causes, the summoning of ambassadors? You tell me.

Horthy apologists find Horthy a noble figure. They say the White Terror was an understandable response to the Red Terror. They say—and there is no reason to believe this—that Horthy was ignorant of the fate of the Jews. They say responsibility for their deaths should be assigned not to Horthy and real Hungarians but to the puppet government of the Arrow Cross. (The director of the above-mentioned Horthy-revising think tank just cuts to the chase: He says Horthy was justified in deporting the Jews.)

As soon as Fidesz came to power in 2010, they put one of their own in charge of the Holocaust Memorial and Documentation Center in Budapest. One of his first steps was removing all mention of Horty’s alliance with Hitler and sanitizing the record of the regime’s participation in the destruction of Hungarian Jewry.

To commemorate the 70th anniversary of 1944, when the Nazis marched into Hungary, Orbán’s government erected a monument in Budapest’s Liberty Square “to the victims of the German occupation of Hungary,” depicting Nazi Germany as a sharply-taloned eagle. It is swooping down to attack the Hungarian people, represented by a weeping archangel Gabriel. It offers no hint that these victims were Jews. Nor that Hungarians—government and citizens alike—were partners in their victimization. Then there’s the grotesquerie of suggesting that everyone in Hungary suffered equally, to the point that Catholic iconography might best evoke the victims.12 Hungarian critics immediately deplored the thing and demanded its removal. The government told them they were imagining things and refused.

Hungary is so innocent, in this recasting of history, that no one need be ashamed, no one need find it indecent, when Hungarian streets are lined with tens of thousands of posters of a sinister, grinning Soros—with the slogan “Let’s not allow Soros to have the last laugh!”—plastered on its billboards, on the metro, even on the floors. Do you really think Hungarians don’t know what that means?

When addressing CPAC, Orbán insisted Hungary had a “zero-tolerance” policy toward antisemitism. (The audience applauded, at least.) But it’s not so. Leaders of Fidesz have rehabilitated one after another Hungarian collaborator and antisemite. They’ve honored Cécile Tormay, one of Hungary’s most obsessive anti-Semites, a woman who argued that Jews were a failed race corrupting the pure bloodline of the Hungarian nation. Orbán praises the Jew-killing war criminal Albert Wass. A magazine controlled by Orbán’s lawyer depicted the president of the Federation of Jewish Communities in Hungary showering in bank notes.

[T]here is a reason Davos Man and his minions single out Hungary for special abuse: it is a country whose democratically elected leadership is unapologetically in favor of the natural family, a traditional Judeo-Christian moral framework, and defending national identity, even if it means controlling borders.

—Rod Dreher

If all of this is lost on American audiences, who have no idea who any of these people were—this to the point that Sebastian Gorka, a member of the Vitézi Rend, was allowed to run around the White House unobstructed—it’s not lost on Hungarians. Soon after these honors were bestowed, Holocaust memorials were defaced and vandalized, a Jewish cemetery was desecrated, pig trotters were draped on a memorial for Raoul Wallenberg, and the 90-year-old former chief Rabbi was abused in the street by a man who told him that he “hates all Jews.”

Orbán primly condemned this.

Jozsef Nyiro, a ghastly antisemite and fascist born in Transylvania in 1918, had been banned from the Hungarian curriculum, like the rest of those scum, until Fidesz rehabilitated him. In 2016, Laszlo Kövér, a leading Fidesz member and Speaker of the Hungarian Parliament, tried to organize a reburial service for him in Romania—which Romania banned. “Romania does not accept commemorations and anniversaries for people who were known for anti-Romanian, anti-Semitic and pro-fascist behavior,” said the Romanian prime minister.

Then Fidesz bestowed the Order of Merit of the Knight’s Cross on Zsolt Bayer, a living journalist who calls Jews “stinking excrement” and says Roma are “animals” that “should not be allowed to exist.” According to Hungary’s Official Gazette, Bayer received the decoration because of his “exploration of several national issues” and as “as a recognition of his exemplary journalistic work.” More than 100 past recipients of Hungarian state awards returned their own honors in outrage. The US Holocaust Memorial Museum sent a letter of protest: “This failure,” they wrote,

must raise serious questions for those who have stood by Fidesz and have justified their support by pointing to the danger represented by the racist, ultranationalist, and xenophobic Jobbik party. Bayer’s racist statements are as extreme as those that emanate from Jobbik.

Immediately, one of Orbán’s media cronies published a story with the headline, “America again wants to meddle in Hungary’s affairs.”

Orbán appointed another prominent and open anti-Semite, Beatrix Siklósi, to run Hungary’s most popular public radio channel.

Wildly anti-Semitic writers have been put on the school curriculum. Jewish ones have been phased out. The Hungarian media insistently refers to Zelensky as “the Jewish comedian.” Eleni Kounalakis, the former US Ambassador to Hungary, described her time there as a “four-year window into some of the darkest corners of antisemitism.”

Here, journalist László Bartus describes the comments in one of the government’s publications, Mandiner:

“He fought his way into the category of the ten ugliest Jews alive,” “Orbán-phobic Khazar,” “disgrace of his kind,” “bastard ÁVÓ Jew,” “You, anti-Hungarian nefarious Jew,” “a ton of shit should fall on you,” “you should be shown as a monkey filled with hurds in a panopticon,” and we could go on. These quotations are intended only as an introduction to the world of anti-Semitic and Nazi comments on the Mandiner website …

We would like to draw your attention to the fact that in all Nazi commentaries there is a sexual connotation, which is also an integral part of classical anti-Semitic literature, that the Jew is a fornicator, the Jew is incestuous, the Jew is gay. The last, needless to say, is inextricably linked to the regime’s pedophile-homophobe law and the hate campaign targeting homosexuals. An ordinary Hungarian anti-Semitic Nazi who fancies himself a Christian knows exactly who these laws are about, Orbán does not even have to say it, he just has to say “liberals” …

These texts appear on a page of a newspaper of the Government of Hungary. In this light, it is a very peculiar phenomenon of the Hungarian press and public life that the online edition of the newspaper Mandiner, which is part of the Central European Press and Media Foundation, established and funded by the Hungarian Government, contains blatant anti-Semitic and Nazi comments that are reminiscent of the press of Hitler’s Germany or even go beyond it, but could be the envy of the Völkischer Beobachter, the official newspaper of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party.

In 2020, the far-right Mi Hazánk party organized a torchlight parade in Budapest to celebrate the 100-year anniversary of Horthy’s ascent. Neo-Nazi paramilitary groups joined the march, fresh off a Nazi memorial march the month before, and the leader of Mi Hazánk gave a speech railing against Jews for ruining Hungary, demanding they be “held accountable.” This happened a few hundred meters away from the Parliament, right in front of the new Horthy statue, which has become a gathering place for events like this, which happen frequently. Viktor Mak of the Kafkadesk in Budapest writes, “Perhaps the success of the party is due to the open secret that Mi Hazánk is supported by Fidesz.”

Despite what even his most vociferous critics might say, Orbán has seemingly stumbled upon the secret sauce for keeping his country’s Jews safe during a time when virtually every other European country is inundated with skyrocketing levels of antisemitism.

Before his trip to speak to CPAC, Orbán addressed the 31st Bálványos Summer Free University and Student Camp. The infamous speech even made the news in the Anglophone media, which may not know much about Hungary but sure knows you can’t talk like that about race-mixing—not to mention his little joke about the gas chambers and his praise for the most racist book written since the Turner Diaries. Appealing to the siege of Vienna and the battle of Poitiers, he explicated his vision in language that caused his advisor Zsuzsa Hegedüs to resign, calling the speech “a pure Nazi text worthy of Goebbels.” On the wings of the audience’s applause, he flew off to Texas to address his American fans: “I’m here to tell you that we should unite our forces,” he said to their rapturous cheers. “The globalists can all go to hell.”

It's not just the rehabilitation of Horthy that’s repulsive, it’s the way Orbán styles himself after Horthy. His rhetoric, like Horthy’s is an unending catalogue of paranoia about leftists and ethnic defilement, punctuated with outbursts of resentment about the mistreatment Hungary has suffered at the hands of the Western powers. His exploitation of Christian symbolism parallels Horthy’s.14 Like Horthy, he depicts Hungary as a fortress, a bastion in Europe, and the protector of Christianity. Diplomats’ descriptions of Horthy during the interwar period and their descriptions of Orbán now are weirdly interchangeable.

Horthy certainly wasn’t the first to evoke these ideas. In 1250, King Bela IV begged for the aid of Pope Innocent IV against the Mongols, citing Hungary’s status as the porta christianitatis—the gate of Christianity—protecting the West. This image has been evoked many times in Hungary, just as it was in every state between the Ottoman Empire and the Christian world. Albanians, Serbs, Romanians and many other people saw themselves the same way. The unusual aspect of this belief in contemporary Hungary, though—beyond the fact that they see themselves this way in 2022, when Ukraine, not Hungary, is protecting Europe against barbarian invaders from the East—is that Hungary resents the rest of the West for its ingratitude for Hungary’s sacrifice. Gallup, conducting a survey on Hungarian historical consciousness, found that 71 percent of Hungarians agreed with the statement, “Hungary was the bastion of the West for a thousand years, and they never rewarded us for it and even now still don’t.” It’s this self-pitying whine, this ressentiment, that links the Horthy and Orbán eras.15

All of this was obviously latent in Hungary, dormant and waiting to be exploited. Orbán hasn’t created these passions ex nihilo. But dormant is just fine. Until Orbán, no major politician had sought to awaken, heighten, and exploit these sentiments for political advantage. No sane politician would. Not only is it disgusting, it’s dangerous.

Thus, once again, Hungary has an internal enemy and an external one, both determined to betray the proud Hungarian people. Now, again, irredentism is an intrinsic feature of Hungarian state doctrine. On the centenary of Trianon, the government unveiled a new memorial, commissioned at a cost nearly US$$17 million. Kate Maltby, a descendent of Hungarian Jews, described plans for the thing as “uncomfortably reminiscent of Holocaust memorials.”

Pedestrians who walk through a 100-meter ramp will be able to read the engraved names of nearly 13,000 Hungarian settlements that Trianon irredentists consider a true part of Hungary—among them, not only towns in Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Ukraine, but more questionably contested parts of modern-day Poland, Croatia, Slovenia, and Austria. The memorial will also feature a fractured granite block and an eternal flame, symbolizing Hungary’s continuing commitment to its fragmented communities.

This is the most sinister aspect of this story. After two world wars, both of which ended in the same territorial fate, you would think Hungarians had learned the lesson: Do not touch that flame. Don’t ever get near it again again.

But if the lessons of history suggest the path you’re following leads to disaster, then history, not the path, must be changed.

I’ll discuss the real implications of Hungarian irredentism, and how it’s related to the headlines we’re now seeing, in the next (and final) essay. For now, here’s an article to which I linked in the beginning, but it might be more interesting to you now.

If you’re new, here are links to this whole series. You’ll want, at least, to read Part I, although it isn’t strictly necessary to understand what follows. If you read them in order, you’ll find that you’re reading a serialized book. I’ve tried to structure it so that every chapter stands alone, but you’ll see the Zusammenhang better if you read them sequentially:

Part I: An introduction to the political trend that defines our age.

Part II: The demos, the ochlos, and the people’s will

Part III: On the downfall of the Roman Republic

Part IV: Caesar and the Internet: Something new under the sun.

Podcast: Dina, Vivek, Monique, and Claire discuss the New Caesarism.

I hope everyone listened to at least a few of them, and I’m proceeding today in the assumption you did.

I assume you’re familiar with them, but if you need a refresher: The Fourteen Points.

So better to protect their lines of communication to India, for example, the British helped themselves to three provinces of the Ottoman Empire that had previously been governed from Istanbul. Together, these provinces formed nothing like a modern nation-state. Voilà Iraq—still nothing like a modern nation-state.

Just slightly more than a century ago. There could well be people alive who remember this day.

Technically, it was not yet Yugoslavia but the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

If you enjoy reading source documents, here’s a wonderful collection of British documents on Hungary between 1918-19. I can get lost in documents like these for weeks—which, come to think of it, is why your newsletter schedule has been a bit erratic.

Besides, it’s so interesting. As horrible as it is.

For what it’s worth, Jobbik now claims it has renounced the fascism and become a normal conservative party. I doubt it.

What the Economist has written, in addition to evincing a stupidity not often to be found in nature, is just factually wrong. Flat-out. Didn’t they think to ask a historian if they could trust what I assume was a Fidesz press release? Did they feel journalistic probity required them to offer both sides of the “Was there a Holocaust” debate?

Said one Austrian MP, stiffly: “This is a complete misinterpretation of EU’s current challenges.” Ah, Eurocrats.

The Archangel Gabriel is the guardian angel of Israel, so hardly exclusive to Christianity, but a graven image of the Archangel? For Jews, this is blasphemous, and praying to angels idolatrous.

The amazing thing about this quote is that the author, Ari Blaff, travels to Budapest to see this paradise (presumably on Orbán’s dime), which he’s learned about from Rob Dreher. He seeks out the Chief Rabbi of the Dohány Street Synagogue. “‘They [Jews] are afraid,” the rabbi tells him. It’s “a misconception to see Hungarian Jews safely nestled in Budapest.” But this does not stop Blaff from celebrating the safety of Jews in Hungary! He concludes: “[P]erhaps there are some merits to learning from a proudly Christian and explicitly conservative country.”

When Orbán first took power in 1998, he moved the Holy Crown of St. Stephen from the National Museum to the Parliament. This means nothing to Tucker Carlson. But it does to Hungarians. They know that Horthy governed in the name of the Holy Crown of Saint Stephen, claiming it was a symbol of Hungarian sovereignty. When Orbán began wrapping himself in that crown, it was a message every Hungarian understood.

Thanks for this Claire - there's a huge number of things that I wasn't aware of. As you say, it puts Orban in a much scarier context.

This recurring theme of weakened nation states with a deep sense of grievance keeps causing problems - Russia obviously, right now, and however the war with Ukraine ends it's unlikely the Russian attitude is going to improve overnight. Hungary sounds like another, albeit smaller, example. One of the miracles of the twentieth century to me was the rehabilitation of (west) Germany and Japan after the war. So far both have done a commendable job of facing up to their past and doing better (although the recent arrests in Germany are perhaps a reminder that there's always someone wanting to hark back to an imagined glorious past).

I was today years old before I knew any of this. It’s both useful and hugely disturbing, not the least of which is that EU leaders knew most of it before granting Hungary membership.