I’m back. I was back on Monday night, in fact, but I had a vacation of such lovely ease and calm that I’ve had the devil’s own time convincing myself to get back to work, not least because work means catching up on the news, which I have every reason to suspect is dreadful. But I’m now stepping back into the ice water of reality. The best way for us all to get caught up on the week I missed is with an edition of Global Eyes, which you’ll soon receive.

First, though …

MIDDLE EAST 101

As those of you who came to class last Sunday know, the departure lounge of Marrakesh Menara Airport did not prove conducive to pedagogy. It was just too noisy. Thank you, Arun, for holding up the fort in my absence.

Did anyone manage to record that discussion? Arun said that he thought Tim might have recorded it. Tim, if you did, would you be kind enough to upload the video to YouTube and send me the link?

If no one recorded it, did anyone take notes? Perhaps you could post those in the comments or in the chat?

If you didn’t take notes, perhaps you could jot down just a few sentences now to let me know roughly what you covered?

Tomorrow, I’ll post the full lesson plan for next Sunday—chronology, notes on the reading, discussion questions, and videos. But since it’s already mid-Wednesday, I’ll send the reading assignment right now.

We’ll be reading one book only this week, and not even the whole book. William Quandt’s Peace Process is available in full at this link. Quandt’s a superb scholar, a very clear writer, and does a terrific job of synthesizing the primary and secondary source material. So:

Read the introduction, which includes some useful observations about how US foreign policy is made, particularly in pp. 5-20.

Skim all of Part 1, on the Johnson Presidency, though if those events are still fuzzy to you, this is a good review.

Skim Chapter 3 (Nixon, Rogers, and Kissinger, 1969–72). But as you’re skimming, make sure that you’re familiar with all the events he discusses in this chapter. If you have any lingering confusion about what happened during this period and when, though, this chapter’s a good review.

Do the same for Chapter 4 (Kissinger’s Diplomacy, 1972–73). If all went according to plan last Sunday, you’ll be familiar with these events, too. If not, though, read this. (Please let me know that you’re not familiar with this, too: I’m assuming you covered this in class; if not, I should know.)

Start reading closely at Chapter 5 (Kissinger and the Disengagement Agreements, 1974–76). Perhaps you covered some of this last Sunday, too? Again, let me know.

Continue through Chapters 6, 7, and 8 (Carter and Camp David, 1977–78; Egyptian- Israeli Peace; and the beginning of the Reagan Administration). We’ll be covering the events in Chapter Eight in more detail, and from different perspectives, next week, when we look at events in Iran and Lebanon. But this chapter will get you started.

Finally, please read Chapter 14, the conclusion. This is especially useful if you’re looking for insight about the present-day crisis.

We’re going to come back to this book, so if the spirit moves you, read all the chapters before the conclusion, too. But all you need for this coming Sunday are the introduction, Chapters 5-8, and the conclusion.

By the way, make sure to read the footnotes, too. He includes large chunks of primary source material in them. They’re also a good guide to further reading.

I’ll say more about this tomorrow, but I figured I should get this to you right away.

A Marrakech Idyll

It’s quite common for people to visit Morocco and fall so passionately in love with the place that they never leave. They renovate old riads and become experts on Moroccan textiles, or they start a new surfing school in Essaouira. They begin new lives as Instagram influencers.

After a few days, I began wondering if I shouldn’t join their ranks.

I’ve even begun looking up Moroccan real estate listings. It’s a lot more affordable than Paris. Even if I didn’t live there full-time, I could buy a riad and rent it on AirB&B when I was away, like every other expat who’s been driving up the price of riads. Wouldn’t it be glorious for the Cosmopolitan Globalist to have a riad in Marrakech? A place we could hold dinners and conferences, invite speakers, and discuss matters of global import? Or just a place to get together in the dark midwinter and have our spirits lifted?

The climate alone would be reason enough. Northern Europe in February is bleak—grey, raw, wet. But Marrakech at this time of year is glorious. The air is dry and fragrant and the skies are perfectly blue. Everything is drenched in golden Mediterranean light.

Here’s the riad we stayed in:

A riad, by the way, is exactly what you want if you’re in Marrakesh. Riads in Moroccan medinas look modest from the outside, but inside, they’re opulent and luxurious. They’re built around a large courtyard that surrounds a garden and a fountain, or a pool. It’s a private, even secret, world unto itself in the middle of the city.

Ordinary houses have windows that face the street, but the windows in a riad face the courtyard, drawing your attention inward, toward the babbling fountain, the orange and lemon trees, the mint tea on the table. The architectural style is cooling, too. I’m not exactly sure why—it has something to do with the water and the shade and the thick sandstone walls. But it really works. So even when the medina is hot, noisy, and chaotic, the riad stays cool, quiet, and soothing. You walk in, and the rest of the world drops away.

I’m so enamored with the idea of a Cosmopolitan Globalist riad that I’ve planned the whole thing already. Before I get carried away, though, how many of you would come to a Cosmopolitan Globalist retreat at a riad in Marrakech?

I need a few more subscribers before I can afford a riad, though. So please, hop to it! Subscribing brings all sorts of benefits, anyway. I’m always racking my mind to figure out what kind of new perk I can offer our paying members, and the more members we have, the better those perks can be:

Marrakech is just charming, though in truth, it’s a gentrified tourist entrepôt and it always has been. (Tourists have been complaining for centuries that Marrakech has been ruined by the tourists.) But the fact that it’s a thriving tourist attraction means that it has everything a European visitor needs to be happy: colored cottons hanging in the air, charming cobras in the square, striped djellebas we can wear at home and reliable high-speed Internet in every riad.

The hippy trail vibe has long since worn off, and if the monkeys, mint tea, carpet sellers, Ali Baba lanterns, and spice shops seem familiar, it’s because they are—they’re the staples of Marrakech-themed decor around the world. But this is Marrakech, and while it no longer feels fully exotic, it’s beautiful and at least slightly exotic. Also, you don’t need to worry that you’ll be sold to Barbary pirates. The sunlight is exquisite, and Morocco is the only country I’ve visited where I’ve genuinely regretted not having spent more money on local handicrafts. Moroccan handicrafts are really nice—they don’t look like a pile of worthless ethnic junk once you bring them home.

Marrakech was once the heart of the Muslim West and the capital of the Almoravid Emirate, an empire that stretched from the Senegal River to the middle of the Iberian Peninsula. The Almoravids laid the city’s original red sandstone in 1070. Trade and commerce have been thriving in its souks ever since. If you’ve been to Seville or Cordoba, Marrakech will look familiar: The Almoravids had a distinct aesthetic genius. Everywhere they went, they left something of enduring beauty. (Exactly at the boundaries of the Almoravid Empire, the magic ends and the architecture becomes forgettable.)

The old city of Marrakech is a labyrinth of tiny alleys, squares, souks, and riads surrounding palaces and mosques. There was, by the way, a large Jewish quarter in Marrakech and their influence remains obvious; a surprising number of shops sell menorahs and Yads. Jews have been there since forever, and though most left for Israel, a lot have been coming back recently. The culture of the city is Arabic, Berber, Jewish, and French, and the old city bustles with life and color.

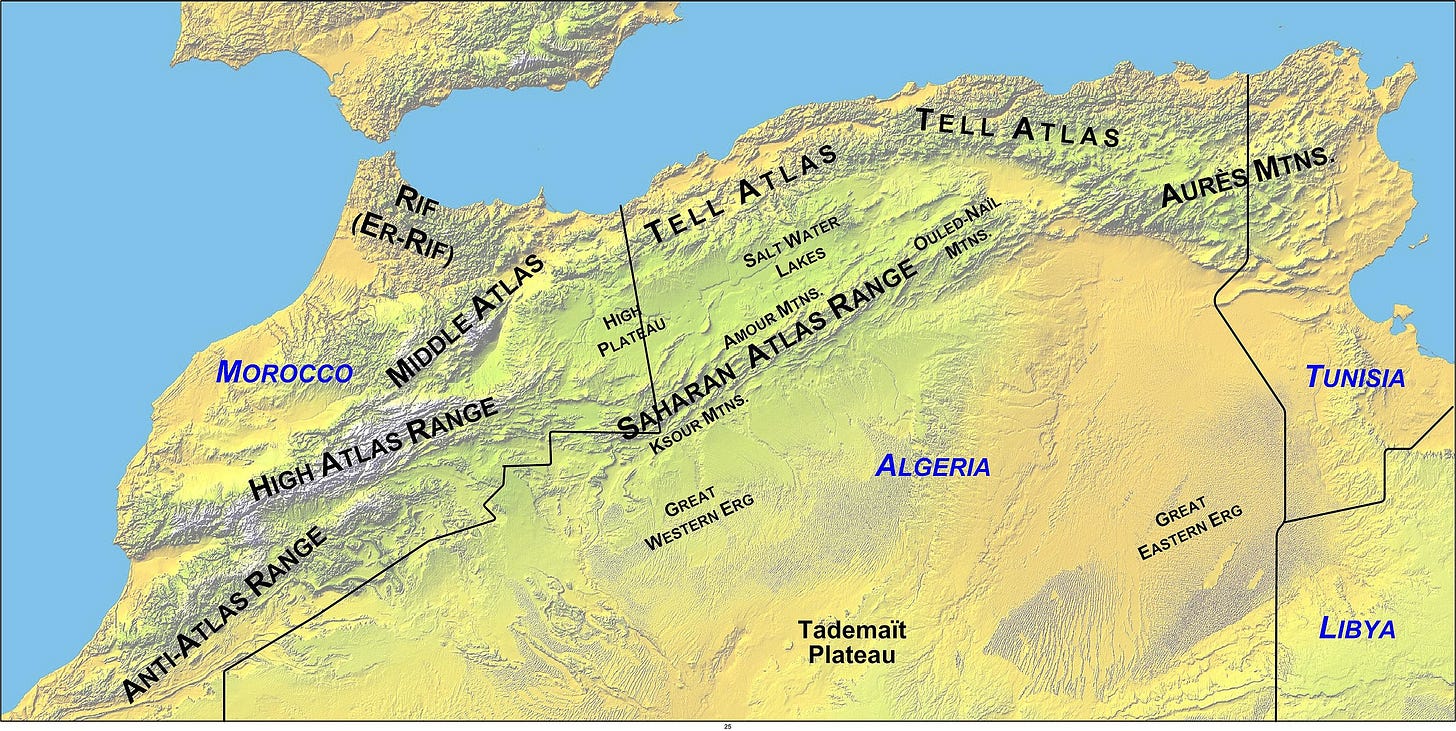

A little over an hour away from Marrakech, you’re in the foothills the Atlas Mountains, where we spent three beautiful nights deep in Berber country—and I must say that if ever you need to take your sister to a place where she’ll chill out and stop screaming “Pass the goddamned Ukraine aid!,” that’s the place to take her.

Morocco has a magnificent light. It is very much like the light of California, which I’ve always loved, but the color of the sky is more intense: It’s an almost purplish cobalt blue.

The smell of those mountains is astonishing. If you grew up there, I’m sure every other place in the world would be a lifeless olfactory disappointment. It involves wood fires, citrus and fig trees, cedar, juniper, lavender, cumin, cinnamon, rockrose, ginger, and many other strong wild sweet smells that I couldn’t identify but I’d now recognize immediately as part of the Atlas Mountain smell. After taking a deep lungful of the mountain air, I suddenly understood the answer to a question I’d never thought to ask: The whole point of incense is to mimic the smell of the Atlas Mountains.

There’s a drought, so the landscape is almost arid but for the fragrant bushes, the wild herbs, the stands of olive trees, and the cedar. The Berber have been living there for as long as anyone can remember, speaking their ancient language and living according to their ancient and highly patriarchal village laws.

As you drive into the mountains, you pass by women’s collectives selling perfumed oils and expensive unguents made of hand-pressed argan oil and herbs. The collectives are part of a larger project initiated by the King of Morocco to transform the status of Moroccan women.

When a monarchy works, is can be an extremely effective tool of governance. When I was last there, in 2013, I spoke to Moroccans who believed they’d been spared the violence of the Arab spring by the wisdom and enlightenment of their King. The case for this is better than you’d think, actually. There had been massive protests in Morocco, as there were in every Arab country. But unlike other leaders, the King didn’t respond with a violent crackdown. Instead, he appointed a constitutional commission to draft a new Moroccan constitution. The commission proposed reducing the King’s power and introducing democratic reforms, and the new constitution was adopted in 2011, after a nationwide referendum. The new constitution, among other things, enshrined equality between men and women in both rights and duties.1 (In 1956, when Morocco gained independence, Moroccan women were legally prohibited from leaving their homes without a male guardian, so this is a significant achievement.)

Mohammed VI ascended to the throne in 1999, following the death of his father, King Hassan II. His dynasty is said to descend directly from the Prophet, and one of the King’s many titles is “Commander of the Faithful,” which makes him the country’s highest religious authority as well as its highest political authority. It was this status that allowed him to overrule the Islamic conservatives who opposed these reforms. By giving wives the right to prevent their husbands from taking a second wife, he all but outlawed polygamy. He raised the legal age for marriage to 18. Women would no longer be required, as a matter of law, to obey their husbands.

Morocco is not a liberal democracy in the sense that we understand the term. As in other constitutional monarchies, the king is the head of state, but he’s also the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces and he maintains complete control over the judiciary. He has the authority, too, to appoint and dismiss prime ministers.

But perhaps this is the best way to introduce democracy. During the Arab Spring, countries ruled by a monarch remained stable. The republics collapsed or descended into savage bloodletting. In the wake of the West’s failed experiment in Iraq, some bitterly concluded that democracy can’t work in the Arab world. But I don’t think this is what the evidence suggests. Democracy in the West emerged gradually. If it emerges in the Arab world, it will also emerge gradually, and probably through a process like this.

If you’re lucky enough to have an enlightened monarch, as Morocco does, it seems you can introduce elements of parliamentary democracy quite successfully. You can also make significant progress in advancing women’s rights. Morocco is a deeply conservative and religious society, and no, Moroccan women don’t yet enjoy the status in society that Western women do. But they might, in time, at this rate.

Moroccan politics, however, were of much less interest to me than the beauty and calm of the Atlas Mountains, and here, a few photos will serve better than anything I can say:

It’s dark and cold in Paris. And I’m afraid to read the news.

Subscribe now, so we can all go back to Marrakech.

Here’s a good article about the alacrity and wisdom with which the King responded to the Arab Spring. Quite a remarkable story, actually. Moroccans adore him.

Torn.

Do I go somewhere beautiful and enjoy the last years of my life in comfort, or do I keep fighting for the United States that we want?

Right now I am compromising by living in Colorado and fighting against the petty tyrannies of an authoritarian leftist legislature.

(For those who wonder what I mean, in a time of major issues such as homeless illegals setting up tent cities in Denver (when the weather can be -10 Fahrenheit), the legislature focuses on regulations eliminating free bags in grocery stores.)

The stupidity of American elected officials is exhausting.

The temptation to walk away is strong.

So envious!!! But so happy you got a good rest!!! Glad to have you back :-)