Destiny and demographics

Why don't secular people in wealthy countries have kids?

We had an interesting discussion in the comments yesterday. Subscribers: If you don’t join or at least read the comments, you’re missing one of the benefits of paying for a subscription. Unlike every other comment section on the Internet, ours is not a sewer. It’s lively, friendly, and intelligent, and often, it’s where I accidentally write a bonus essay. I never mean to do that. But sometimes I reply to someone and realize that what I’ve written was more interesting than what I’d planned to send out that day. So do check out the comments, meet other subscribers, make friends. Anyone who pays to read the Cosmopolitan Globalist is probably someone who enjoys thinking about the same things you do.

The conversation arose in response to the item I posted the other day about South Korea’s demographic disappearance: Korea’s plunging birthrate alarms government. Total fertility—the number of children per women—plunged to .78 last year, which is astonishing. The replacement rate is 2.1. In Japan, the number was .81. This is obviously catastrophic for the country’s future, and it’s catastrophic for its economy, right now: South Korea is confronting massive manpower shortages. I remarked of the article that the population bust Peter Zeihan warned about is here, and I said:

This seems to happen to every country that industrializes and no one knows what to do about. (Yes, Israel is an exception, but until recently, so was the United States. Israel will probably have the same problem soon enough.)

In response, our reader WigWag wrote:

Devout people make babies; secular people don’t. It’s really that simple. As the United States becomes more secular, its birth rate will continue to decline. Israel has one of the highest birth rates in the world because the ultra-Orthodox routinely have more than six children per couple. That’s double the rate of the rest of Israel’s Jewish population and three times the rate of secular Israeli Jews. The religious Zionist population (less observant than the ultra-Orthodox, but observant nonetheless, also have a very high birth rate. Israel’s secular population (the citizens freaking out over a minor judicial reform) has a much lower birth rate than the rest of the nation’s Jewish population and its Arab minority. Secular Jews in Israel are likely to enter a demographic tailspin just as reform and secular Jews in the United States have. Societies that eschew religion are committing demographic suicide all over the world.

No comment on the part about “freaking out over a minor judicial reform.” To my surprise, though, I actually agreed with the rest of his remarks. You can read my long response to him here, and to make it even easier, I’ll append it below, slightly edited for clarity.1 But on reflection, I think this theory is incomplete. And on further reflection, I think the theory is wrong.

There is, indeed, a close correlation, around the world, among a cohort of phenomena: Industrialization, urbanization, secularization, and declining birthrates. They tend to happen in that order. But why?

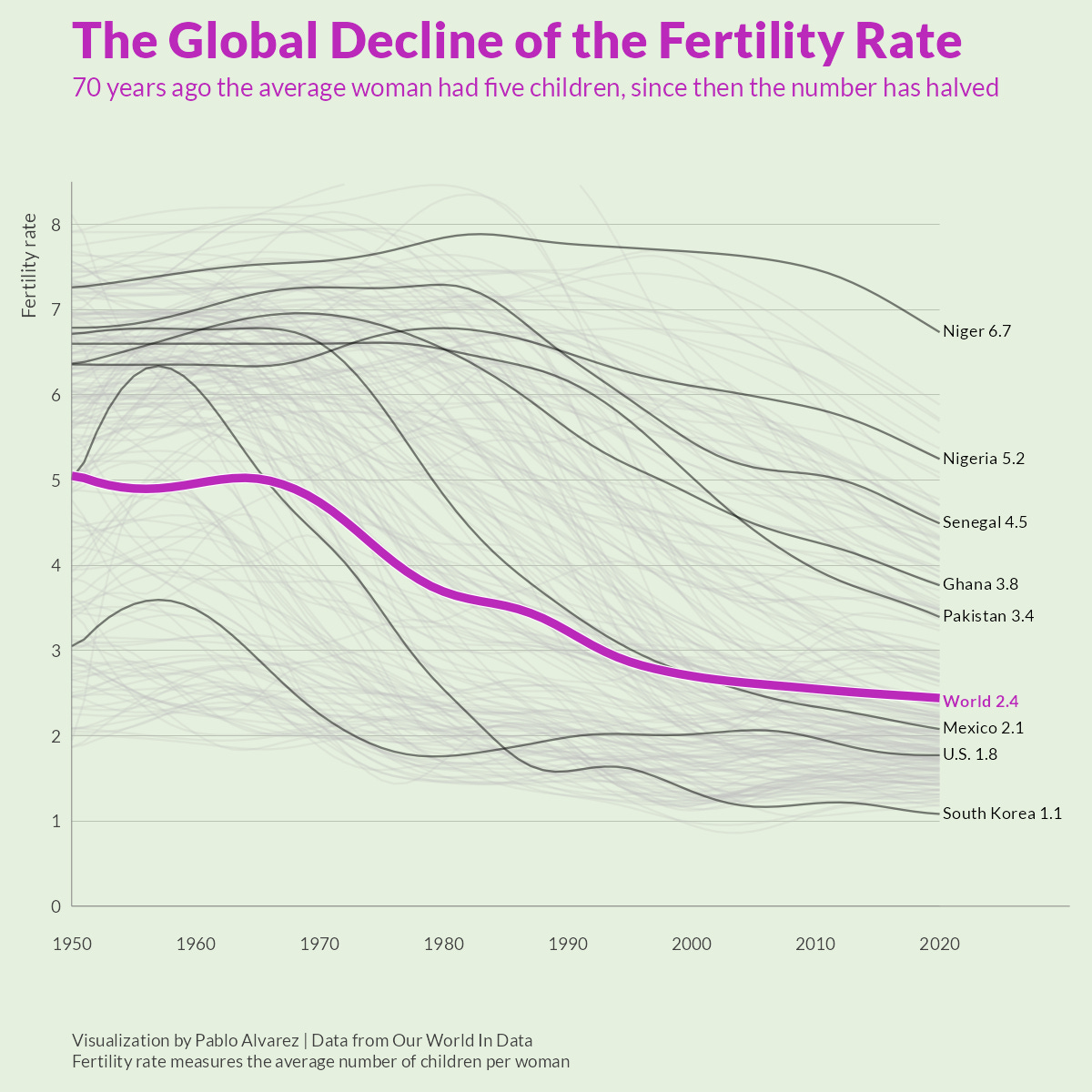

For the past 70 years, fertility rates have declined, globally, by fifty percent.

There’s no firm consensus about why, but there are a number of interesting conjectures with a great deal of empirical support to them. It turns out that the degree to which women are educated is the most important variable.

In 1960, Gary Becker wrote An Economic Analysis of Fertility. This is, I think, the seminal idea. He argued that you could model the demand for children in much the way you could model the demand for any other good. Fertility decisions, he proposed, are made by rational individuals who weigh the costs and benefits of having children and make their decisions based on preferences, resources, and other opportunities available to them. Therefore, he concluded, the opportunity cost of having children will be a key determinant of fertility decisions: Having children requires a significant investment of time and money. It could otherwise be used for work or leisure.

Becker argued that changes in the economic environment—particularly, greater opportunities for women in the labor force and changes in the cost of raising children—will affect fertility decisions. In developed countries, he noted, high income has a negative effect on fertility; this is because people with higher incomes face greater opportunity costs for each additional child. In societies where mothers spend much more time with their children than fathers—still the majority of human societies—the opportunity costs are mostly born by the mother. So of course, as soon as women are educated and have better opportunities, they’ll want to have fewer children. What’s more, educated women know how to use contraceptives.

This in turn causes a feedback loop: Educating women reduces fertility; reduced fertility means you can afford to educate more of your daughters; lower fertility means the school system can give each pupil more attention; and within a few generations from the emancipation of women, you’ll get someone like me: a woman with a doctorate from Oxford who’s the end of her genetic line.

This is a wholly plausible story and it’s compatible with the data. Highly compatible.2 You can more-or-less predict a country’s fertility rate by the number of years of women spend in school:

This explains the anomaly of Israel, too: Ultra-orthodox men spend a lot of time studying, but what they’re studying has no value in the workplace. They study the Torah. They don’t study anything else. This is why 35 percent of ultra-orthodox men work in jobs with low pay and low productivity, and 50 percent don’t work at all. The ultra-orthodox don’t educate their children in core-curriculum classes like math, science, or English. Nor do they send them into vocational studies. They can’t study the secular books because they’re not kosher. They spend their days bent over prayer books, which is very good for the soul, I’m sure, but lousy for the CV. From an economic point of view, the ultra-orthodox may as well be completely uneducated. This is a very sensitive issue in Israeli society, as you can imagine, particularly because ultra-orthodox men don’t serve in the military, either.

And this is why the poverty rate among the ultra-orthodox is twice as high as that of the general population. If we look at fertility choices strictly in the terms I suggest above, you don’t need to ask what the ultra-orthodox believe about being fruitful and multiplying to understand why they’re multiplying more fruitfully. (You also don’t need to ask why secular Israelis are “freaking out” about a significant change in the country’s balance of power in favor of the ultra-orthodox.)

But there’s an interesting trend in Israel. Ultra-orthodox girls are now more likely than boys to study practical, secular subjects, because someone has to put food on the table—and they want to get jobs to support their husband as he studies the Torah. Often, they’re the family’s main breadwinner, and as Gilad Malach writes,

Over time, however, what began as a necessity has become widely accepted as a favorable and preferred state of affairs, and one that is supported by the ultra-Orthodox education system. Thus, today’s education and vocational training system for ultra-Orthodox girls is oriented—from the very beginning of elementary school—towards ensuring that they will be able to find employment as adults. The impact of this shift quickly became apparent, as employment rates among ultra-Orthodox women rose from 51 percent in 2003 to 77 percent in 2019, reaching almost the same level as among other Jewish women (83 percent).

The girls still aren’t encouraged to study what they’d need to study to get good jobs, but increasingly, they’re encouraged to study subjects that increase their opportunities.

This is why I suspect that over time, Israel’s birthrates are apt to follow the usual trajectory for the developed world. As soon as women get educated, the cat is out of the bag. It may not be happening as quickly in Israel as elsewhere, but it will probably happen, because modern, economically sophisticated societies place stringent demands on people. If you don’t have a job, you starve; if you don’t get an education, you’ll have a miserable job; if your men refuse to work, your women will have to do it; and if they get educated enough to do it well, your birthrate is going down. Way down.

This correlation holds within societies as well as between societies, by the way. The less-educated the women, the more kids they’ll have.3

Now, while the correlation between education and secularization—and both with low birth rates—is tight, I’m not quite sure which way the causal arrow goes: Do secular people educate their girls? Or do educated people secularize? Or might it be that industrialization forces people to educate their girls, for economic reasons, and causes them to secularize, for independent reasons? This is all a bit tangled up. It will be interesting to see whether educated ultra-orthodox women secularize.

Another variable clearly correlated to declining fertility is the percentage of women in the workforce—a correlation that may also be explained exactly as Gary Becker explained it. Why have women entered labor markets in such vast numbers in the past century? It’s not because they’ve secularized. It’s because they’ve been able to do so, for the first time, and they’ve been able to do so because of the massive changes in the structure of the economy: The shift from a primarily agricultural economy to one based on manufacturing and services creates far more jobs in which women are not at an obvious disadvantage because they’re smaller and weaker; this, plus the rise of labor-saving consumer durables, explains almost all of the change.4 What’s more, to achieve a fully-developed economy and all of its attendant benefits, women must enter the workforce. Failing that, you get caught in the middle-income trap.

There are other determinants of fertility to consider. There’s a strong correlation between decreasing child mortality and decreasing fertility, for example. Simply put, parents realize they don’t need spares. Restrictions on child labor, likewise, reduce fertility: If you can’t put your kid to good use, having an extra one is a net drain, not a gain, on your household finances. (Changing moral perspectives on child labor also tend to accompany industrialization.)

So the growing cost of having a child in the developed world is clearly a factor. The more developed an economy, the more years of education your kid will require to participate in it gainfully, and the more sense it makes to concentrate your investment in a single kid, or two, instead of half a dozen. Also, with economic development comes urbanization, and with urbanization, stiff competition for housing. It’s one thing to have seven kids if you live on a farm and you can send the tykes off to slop hogs and pull a plough all day; it’s quite another if you live in a one-bedroom apartment that costs more than three farms and your kids expect you endlessly—and expensively—to amuse them.

When you add all of this together, declining fertility in wealthy societies can be explained—and explained very well—without reference to secularization. But now add the effect of secularization. Why secularization should lead to low fertility is intuitively obvious: If God tells you to have lots of children, you’re more likely to do it. And indeed, this is what we see, although what we see is slightly more subtle than this, in an interesting way; to wit, as Landon Schnabel discovered, your fertility will decline if you live in a secular society, irrespective of your personal religious beliefs:

Secularism, even in small amounts, is associated with population stagnation or even decline absent substantial immigration, whereas highly religious countries have higher fertility rates that promote population growth. This country-level pattern is driven by more than aggregate lower fertility of secular individuals. In fact, societal secularism is a better predictor of highly religious individuals’ fertility behavior than that of secular individuals, and this pattern is largely a function of cultural values related to gender, reproduction, and autonomy in secular societies. Beyond their importance for the religious composition of the world population, the patterns presented in this study are relevant to key fertility theories and could help account for below-replacement fertility.

This is another reason why, I figure, Israel will approach Western norms sooner or later—although the tipping-point may have already been reached: The secular are now slightly less than half the society.

This still doesn’t answer the question, “What is it about economic development, if anything, that secularizes a country?” I don’t quite know. But I do know they’re not necessarily co-occurring processes. In Turkey, for example, we see the same relationship between economic development and declining fertility as we see elsewhere in the world—but we don’t see secularization.5 So it is possible to modernize without secularizing. But it won’t spare you from demographic doom.

In all, then, I agree that there’s a connection between secularization and declining fertility, but it’s just one connection—and it may not be a causal one, nor even a particularly critical one.

My response to WigWag

I agree. The industrialization-urbanization-secularization relationship is extremely robust, globally. I too thought the US and Israel were exceptions to that rule (and thus to the population bust), but seeing how quickly it happened in the US makes me think it will happen to Israel, sooner or later. It happened later in the US for reasons I don’t fully understand, but it sure happened. I don’t understand why the relationship between one and the other has been so tight, but there’s no doubt it is that tight.

So when you say, “Societies that eschew religion are committing demographic suicide all over the world,” what you’re really saying is, “Societies that modernize and industrialize are signing their own demographic death warrant.” But as people keep pointing out in the context of climate change, there’s no way to keep people from industrializing and modernizing: The benefits of it are overwhelmingly obvious, and asking the undeveloped world to remain poor and primitive to prevent carbon from entering the atmosphere—or to protect their faith and their fertility—is a non-starter.

So what’s the solution? For now, there’s actually no problem at all for any developed society that can overcome its aversion to immigration. People from poor countries are desperate to move to wealthier ones. There’s no reason there needs to be a labor shortage of any kind, in any industry, in South Korea, or in any developed country. People are dying, literally, to move there and take those jobs.

But developed countries, we’re seeing, are highly averse to significant levels of immigration—despite all the evidence indicating that culturally, human beings are plastic, and no matter where the immigrants come from, within two generations they’ll be more or less indistinguishable from the natives. Not genetically and phenotypically, but linguistically and culturally.

But people don’t believe this. They find immigration profoundly threatening. Many prefer literally to commit demographic suicide, as you put it—and also to immiserate themselves, because no economy, and certainly no system of care for the elderly, can function without young people—than to envision their cultures and civilizations surviving and thriving via transmission to people who are 99.9 percent identical in their DNA, but who were born in another country.

I have no doubt at all that first-generation immigrants to South Korea from Afghanistan, say, might struggle a bit to adapt, but their children would be perfectly good South Koreans: They’d speak Korean without an accent, they’d understand every nuance of the culture, they’d contribute gainfully to the economy. And their children, in turn, would be culturally indistinguishable from South Koreans and upwardly mobile.

But the primitive belief that being South Korean is a matter of blood, not a matter of language and culture, is preventing South Koreans from saving their economy and their civilization. Unless this changes, within a few generations there will be no South Korea at all, which would be a loss to humanity. It would be an even bigger loss if Western civilization (in the broad sense, meaning the liberal democratic world) perished owing to this fallacy, and because the West industrialized and developed first, it’s at great risk of doing so.

I do wonder what effect technologies such as artificial wombs might have on fertility rates: If women are able to have children without the danger, pain, and inconvenience of pregnancy, might they be more willing to do it? France managed to get its fertility rate nearly to replacement between 1993 and 2013 through ultra-pro-natalist policies: If you have a baby in France, you have guaranteed healthcare and childcare (from the very first day); you have generous parental leave; family allowances; huge tax advantages, and many other benefits. (Causation is not equal to correlation: We don’t know for sure this is why birth rates went up, but most French women attribute it to this, and there’s a consistent relationship, in Europe, between pro-natalist policy and fertility.) French birth rates plateaued during the Great Recession, though, and then started dropping again. Now it’s back down to 1.8, from a high of 2.0 in 2013, which was oh-so-close to replacement:

So I don't think it’s inconceivable that if you make having children a lot easier—and artificial wombs would certainly do that—fertility will rise. (By the way, that's another factor in Israel’s fertility: Their policy is just as family-friendly as France’s.)

Note: France’s fertility is one of the highest in Europe—it’s Europe’s fertility champion. But it’s still not high enough to keep going, not without immigration. You can’t forcibly un-secularize people (unless you like the way Iran is governed), and you certainly can’t de-industrialize and un-modernize people (unless you like having a life expectancy of 30 and famine). So it’s policies like this or immigration.

You know where I stand: I think immigration is a terrific solution. It not only solves the economic problem without forcing people to have children they don’t want, it saves the lives of families like the Sahilis. But my view, unfortunately, is not shared widely, or at least, not widely enough to be accepted without causing a political crisis. I don’t think immigration should be forced upon an unwilling population.

I do think this case should be made to people more plainly, though. If you don’t like immigration, you must have more babies. And if you don’t want to have more babies, stop freaking out about immigration. Otherwise, there will be no more of you. There will be no one to take care of you in your old age; your standard of living will collapse, and soon, you’ll be extinct.

Perhaps if people understood this better, they would grasp why immigration is not a sinister plot against them, but the only solution to a problem they don't otherwise seem to wish to solve.

After writing that, I realized I’d expended all my writing energy for the day and had none left for the newsletter. I should spend less time reading the comments.

See, e.g.: The trade-off between fertility and education: evidence from before the demographic transition; and Long-term determinants of the demographic transition, 1870-2000. The author writes: “When average years of primary schooling grow from 0 to 6 years, fertility should decrease by about 40 percent to 80 percent.” And what do you know, it does.

This is also compatible with a fascinating study I once read. Alas, for the life of me, I can’t remember who wrote it or where I read it. But the gist of it was: If you want teenage pregnancy rates to go down, you don’t need to bother with sex ed, and you certainly don’t need to waste your time giving them creepy lectures about abstinence. By far the most important factor in determining whether teenage girls get knocked up is whether they can imagine doing something else with their lives. It seems that if they have something else they’d rather do, teenage girls are quite capable of figuring out by themselves how not to get pregnant. Unfortunately for the future of humanity, if you get a girl to decide she doesn’t want to be a teenage mother, she’s quite likely to decide she doesn’t want to be a mother at all.

I probably don’t need to point out the obvious, but I will anyway: This suggests that the trend in any developed society will be toward dysgenic fertility—a population that gets dumber. This explains quite a bit, alas.

Only in a highly industrialized economy—or to be precise, an economy that’s developed so much that it’s come through the other end of industrialization and is now chiefly service-based—would people come up with the idea that the size and strength differential between men and women is so basically insignificant that men can readily become women and vice-versa. For more on the often-insufficiently appreciated effects of this economic transition on relations between men and women, see my (very) long essay, The Years of Living Hysterically, particularly Part II, “Enter the Women.”

Here’s a good article about this: Disentangling the Roles of Modernization and Secularization on Fertility: The Case of Turkey.

The takeaway from this discussion is that the Law of Unintended Consequences is still in operation, and that it doesn't care what people believe or want.

If a declining birthrate is the inevitable consequence of development and modernization, then developed, modernizing societies are doomed to decline and stagnation. In the context of development and modernization, the most valuable form of capital is human capital. When that is lacking, development and modernization will come to a halt, then go into reverse. The grim irony of the situation in which we find ourselves is that modernity itself is drying up the sources of that capital.

Immigration may to a certain extent retard that process but can never reverse it. In the American context, immigration doves seem unable to grasp the social and cultural implications of large-scale immigration as a remedy for demographic decline. My own opinion is that it would create a permanent underclass doing those proverbial "jobs that Americans won't do"—an underclass ghettoized by language and cultural differences, exacerbated by low educational levels. Among this country's progressive elites, the traditional American "melting pot" has fallen into disrepute, and they'd see such immigrants as fodder for their debased ideology of multiculturalism. In short, immigration on a large scale would further destabilize American society. I leave aside the question of moral propriety raised by an immigration policy seeking to cream off the best educated members of Third World countries. The medical practice to which my doctor belongs includes a Nigerian physician who emigrated to America in his early thirties. That's one less physician in a country that sorely needs physicians.

As for the cause of the fertility decline in America and similar countries, I think it's too convenient by half to ascribe it to abstract factors like "modernization" and "development." Ideology has been at work on American women since the Sixties. Women's liberation, feminism, call it what you will, began by assuring women that they could have it all and when it turned out that no, they couldn't have it all, feminism began dictating to women what they should and should not want. That in the eyes of contemporary feminists, the position of Senior Vice President of Marketing at Giganticon Corporation is more desirable than marriage and family, is an undeniable reality. Because its original promises didn't pan out, feminism felt compelled to go to war with the institutions of marriage and the nuclear family. An unmistakable sign of this is the pro-choice tendency to portray pregnancy and childbirth as a dangerous, even life-threatening, medical condition.

American men too have taken their cue from feminism. Having been declared optional accessories, and being aware that women have easy access to birth control and abortion, today's young men don't see why sexual satisfaction should involve commitment.

That American women—and in the long run, men—have not been made happier by these formulations is a reality too obvious to belabor. And it hasn't been a day at the beach for American children, either. We hear a lot about "child-friendly policies" that turn out in practice to be proposals for lifting the burden of parenthood from parents and shifting it to the taxpayers. How friendly is that to the kids, really? How likely is it, indeed, that government programs can fill the void left by all that we've lost, all that we've discarded?

I find it difficult to avoid the conclusion that modernity is a suicide pact. Its technological side is, admittedly, a marvel. But the price—socially, culturally, spiritually—was high. And a balloon payment, it seems, is coming due.

Claire, there’s another factor related to fertility decline that hasn’t been mentioned yet; young men and young women are simply having much less sex than they once did. This fact is much discussed in both Korea and Japan. See,

https://m.koreatimes.co.kr/pages/article.amp.asp?newsIdx=208285

and

https://toyokeizai.net/articles/-/56360

It would not surprise me if the same reality was beginning to take hold in the United States and Europe.

Why young men and women are less interested in sexual relations than they once were is an interesting question. The ubiquity of pornography on the Internet may play a role. Another factor might be hook-up sites that facilitate sex but not longer term intimate relations that lead to childbirth.

But I suspect that at least in the United States it is more than that. Changing customs between men and women that started with the feminist movement and reached a climax with the “me too” movement has made it far more challenging for men and women to meet and have sex.

At many universities throughout the United States sexual partners (but in reality, males) are required by university rules to solicit affirmative consent for each and every incremental sexual act leading to copulation. This must contribute to a disincentive for young people to have sex.

Add to this the potential for young men to be accused of sexual abuse if a female partner later regrets her decision to participate in sexual relations and you have another major disincentive. The standard of proof (demanded by both the Obama and Biden Administrations that Trump temporarily eliminated) is so low, that sanctioning an innocent male is remarkably easy.

In addition to school, another place for young people to meet and form lasting relationships that lead to marriage and children is the workplace. Unfortunately, thanks to the excesses of the “me too” movement, it is very difficult for young people to meet partners at work. Unless the young people in question are on the identical level of the workplace hierarchy, even the most innocent and consensual relationships can be construed as harassment. We also shouldn’t forget that in certain quarters, heterosexuality is now viewed by society as inherently oppressive compared to other sexual proclivities.

Finally, there’s another factor that I wonder about. As sexual roles are evolving away from what they have been throughout much of human history, is it possible that men are becoming “feminized” and women are becoming masculinized? If this is indeed happening, is it possible that women are finding it harder to find men that they are sexually attracted to?