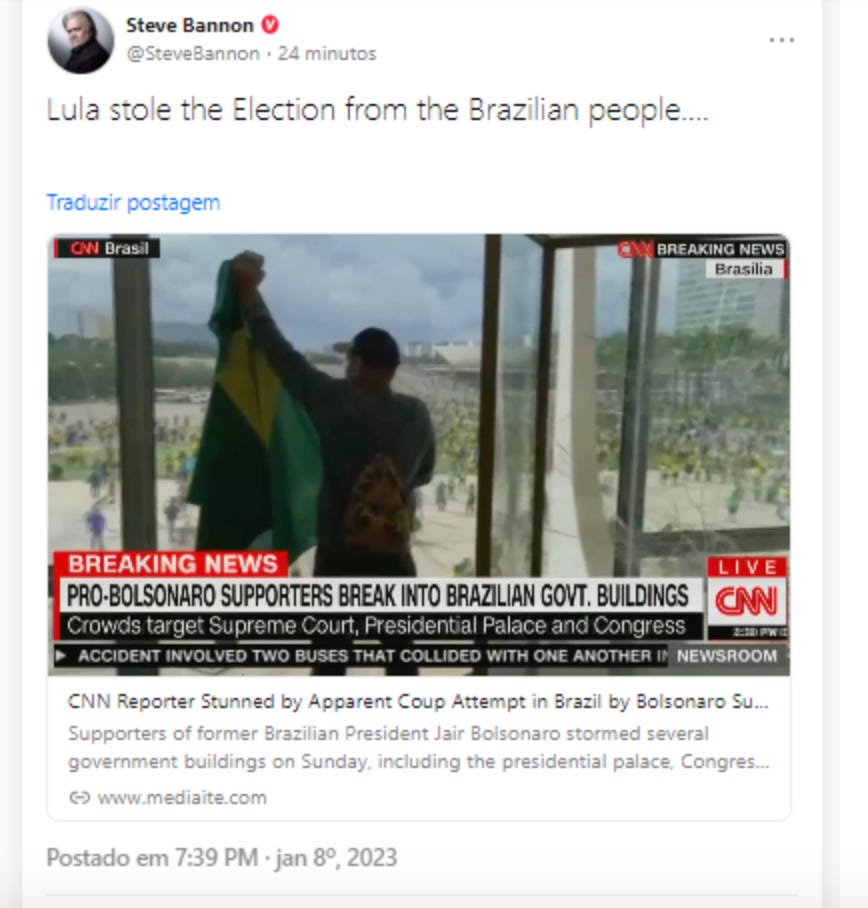

What happened on January 8 in Brasília closely resembled what happened on January 6 two years before in the US Capitol. This is not a coincidence. The same circle of American radicals—Steve Bannon, in particular, along with a number of other figures closely associated with the insurrection in the Capitol, such as Mike Lindell, the My Pillow guy—were intimately involved in the planning and incitement of the insurrection in Brasília. If you were in any doubt that Trump and Bannon intended to foment the violence we saw at the Capitol on January 6, you now have your answer. They intended it. Bannon was so undeterred by our response that he tried it again.

Too many Americans, I suspect, looked at the scenes in Brasília, noted their similarity to the scenes at the Capitol, and moved on without asking why. It’s not just a matter of cultural contagion by means of images on television. It’s much more than that.

Obviously, there were important differences between the two uprisings. The most important was that the Brazilian uprising was performative. Lula had already been inaugurated. There was no chance of preventing what had already happened. Bolsonaro had already decamped to Florida, where he had gone strangely silent. There’s no evidence (yet) that, beyond insisting for years that the election would be fraudulent, he personally involved himself in the uprising. But there’s more than enough evidence that the mob was motivated by the belief, supported by no evidence, that the election was stolen—a lie promoted on social media by exactly the same people who promoted it in the United States.

We’re exporting mayhem. A specific and identifiable group of people are involved. They’ve done this in the United States, they’ve done it in Brazil, and presumably, they’ll do it again. We need to investigate this. We need to prosecute the ones who have broken American laws. If we can’t manage to inspire a sense of urgency in Merrick Garland, we should encourage Brazil, if it proves they’ve broken Brazilian laws, to request their extradition.

Most of the key organizers and propagandists of the January 6 insurrection were involved in Brazil’s.

That the same playbook was used to foment Brazil’s insurrection is also a much deeper problem. We now know that what happened in the US on January 6 wasn’t a one-off. What does this suggest? Perhaps it suggests that the epistemic chaos of the social media era is not compatible with democracy and ordered liberty? A particular kind of lie, conjoined with social media, can destabilize even the most established democracies. If the US can be subverted this way, every democracy is vulnerable, and if Americans feel any responsibility at all to the cause of democracy, we have to devise solutions to this problem.

One solution could be legislative. What Bannon and Co. have done, in the US and in Brazil, can be described precisely, and perhaps it can be prohibited with targeted legislation that is not so broad as to threaten crucial civil liberties. We need to at least think about this before they do it a third time.

We already have the basic legislation: The Smith Act:

18 U.S. Code § 2385 - Advocating overthrow of Government: Whoever knowingly or willfully advocates, abets, advises, or teaches the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying the government of the United States or the government of any State, Territory, District or Possession thereof, or the government of any political subdivision therein, by force or violence, or by the assassination of any officer of any such government; or

Whoever, with intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any such government, prints, publishes, edits, issues, circulates, sells, distributes, or publicly displays any written or printed matter advocating, advising, or teaching the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence, or attempts to do so; or

Whoever organizes or helps or attempts to organize any society, group, or assembly of persons who teach, advocate, or encourage the overthrow or destruction of any such government by force or violence; or becomes or is a member of, or affiliates with, any such society, group, or assembly of persons, knowing the purposes thereof—

Shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than twenty years, or both, and shall be ineligible for employment by the United States or any department or agency thereof, for the five years next following his conviction.

Like the assault on the Capitol on January 6, the assault in Brasília was an attempt to overthrow or destroy the government. But it was a very particular kind. The hallmark was a massive mob, fueled by massive lies. The delusion, too, was a very particularly delusion: In both cases, the mobs sincerely believed that electronic voting machines were rigged, despite the lack of any evidence for this proposition and extensive audits indicating that this had not happened.

Will Saletan correctly describes the key element in the Bulwark. “This isn’t a fight over ideology,” he writes. “It’s a fight over information.”

In a traditional anti-democratic coup, the military or the armed opposition seizes power in overt defiance of a previous election. But that isn’t what happened in the United States two years ago. Donald Trump summoned a mob to Washington and unleashed it on the US Capitol not by calling for the overthrow of the government but by claiming, falsely, that he was the duly elected head of the government. He used fictitious allegations of election fraud to manipulate his followers. They stormed the Capitol believing that they were defending, not deposing, the winner of the election.

The Smith Act has a complicated Constitutional history. It was used to prosecute American communists for subversion. It should not have been. After a string of convictions, the Supreme Court began ruling against the government in such cases, beginning with Yates v. United States. The Smith Act, said the court, couldn’t prohibit teaching the duty to forcibly overthrow the government as an abstract principle, divorced from any effort to instigate action to that end.

The corollary, though, is that it can be used to prohibit teaching the duty to forcibly overthrow government when it is conjoined with an effort to instigate action to that end. This idea could be used to update the Act and criminalize this kind of incitement.

The Smith Act could, therefore, read:

Whoever, with intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any such government, promulgates the lie that a valid election was stolen, with the intent of convincing a mob that the government is illegitimate and must be violently overthrown—

Shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than twenty years, or both, and shall be ineligible for employment by the United States or any department or agency thereof, for the five years next following his conviction.

Is that constitutional? I’m not sure. But if the Smith Act is constitutional, surely that should be, too. If you can criminalize teaching the duty to overthrow the government (provided you really are trying to overthrow it) I don’t see why this wouldn’t pass muster. The government does, after all, have the right to prohibit its own overthrow, and if it doesn’t, there’s something wrong with the Constitution. So if that’s a well-established limit on the First Amendment, why wouldn’t this be, too? The risk is real. We’ve now twice seen the same people inciting mobs to believe a valid election was stolen as a means of unseating the government. That’s a clear and present danger if ever there was one.

We can’t just throw up our hands and say, “But it’s their First Amendment right to lie!” It can’t be, any more than it was Sam Bankman Fried’s First Amendment right to lie. In some contexts, lying is criminal. This particular lie is meant to turn citizens into a mob and use them as a battering ram to overthrow lawful governments. Any pretense that Bannon and Co. did not specifically intend to do that on January 6 at the Capitol died in Brasília. Once, perhaps, is an accident—a lie that got out of hand. Twice is not.

We have more legislation we could adapt:

18 U.S. Code § 956 - Conspiracy to kill, kidnap, maim, or injure persons or damage property in a foreign country: Whoever, within the jurisdiction of the United States, conspires with one or more persons, regardless of where such other person or persons are located, to damage or destroy specific property situated within a foreign country and belonging to a foreign government or to any political subdivision thereof with which the United States is at peace, or any railroad, canal, bridge, airport, airfield, or other public utility, public conveyance, or public structure, or any religious, educational, or cultural property so situated, shall, if any of the conspirators commits an act within the jurisdiction of the United States to effect any object of the conspiracy, be imprisoned not more than 25 years.

This, too, could be amended: Whoever, with intent to damage or destroy specific property situated within a foreign country and belonging to a foreign government, promulgates the lie that a valid election was stolen, with the intent of convincing a mob that the government is illegitimate and must be violently overthrown—

Similarly, 18 U.S.C. § 2339A and 18 U.S.C. § 2339B prohibit providing material support to foreign organizations that engage in terrorist activities. Should we not amend this to prohibit providing support to foreign organizations that engage in the effort to overthrow a government by inciting a mob to believe a valid election was stolen? We can’t just allow these people to jet around the world trying to overthrow the governments of our allies, can we?

Meanwhile, can’t Bannon and Co. be prosecuted under 18 U.S. Code § 953?

18 U.S. Code § 953 - Private correspondence with foreign governments. Any citizen of the United States, wherever he may be, who, without authority of the United States, directly or indirectly commences or carries on any correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government or any officer or agent thereof, with intent to influence the measures or conduct of any foreign government or of any officer or agent thereof, in relation to any disputes or controversies with the United States, or to defeat the measures of the United States, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both.

Recall that the US Senate, on September 28, unanimously adopted a resolution calling on the United States to “continue to demonstrate against efforts to incite political violence and undermine the electoral process in Brazil.” What Bannon and his buddies did specifically undermined the clearly expressed will of the United States Senate. It may not be illegal, under the law as currently written, but it is certainly an outrage, and if it’s legal, it shouldn’t be.

Whether or not the US manages to prosecute or otherwise constrain this crew—I have no idea what’s going on in the Justice Department, but it sure doesn’t seem as if we’re able to do it—other democracies need to protect themselves. None of these people should ever be permitted to set foot again on the soil of any country that cherishes its own democracy. No visas. No entry. For God’s sake, they are not visiting to see the Cathedral. How many times do you have to attempt to overthrow a democracy before the world cottons on?

Next year we have France and Hungary, in April or May. Then we have Bolsonaro in October and then the midterms. This is the chessboard. Will be fascinating, right Matthew?—Steve Bannon to Matthew Tyrmand, on his podcast

All movements are interconnected and interdependent—Tyrmand to Bannon

Brazil, with this Lula dispute against Bolsonaro, will be the last bastion of us trying to say something.—Bannon

I think the most important election in the world is that of Brazil—Tyrmard

Talking about 2022, why is Facebook saying that it will increase its efforts, in quotation marks, anti-disinformation, for the Philippines, for Brazil, for France, for Hungary, for the U.S. midterm elections? It’s because Facebook is trying to shape the world in its new order—Jason Miller

They are using ballot boxes that come from Venezuela. The people want auditable and paper ballots in Brazil.—Bannon

You may be wondering what evidence there is for Bannon’s involvement. Brazil is, after all, a foreign country. It has its own complex history, its own language, its own culture, its own dynamics. We shouldn’t assume that it is relevantly akin to the United States, however similar those scenes might have looked. How influential could someone like Steve Bannon really be in Brazil?

At first, I thought the answer was, “probably not that much.” In fact, this essay began as my usual complaint: “It’s not all about us. It’s narcissism to believe that other countries are just like the United States. We must understand Brazil on its own terms. Probably, Brazilians have no idea who Steve Bannon and his friends are.”

But the more I looked for evidence to support my thesis, the more I realized I was wrong. Brazilians know damned well who they are. That’s why the Brazilian Federal Police detained and interrogated Jason Miller and Gerald Brant after the 2021 CPAC conference in Brasília:

The Federal Police took the testimony of former Trump advisor and Gettr social network founder Jason Miller and businessman Gerald Brant, a friend of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and a link between him and his family with the American right, in the morning of Tuesday in the context of the digital militias inquiry, which succeeded the inquiry of undemocratic acts and investigates possible organized actions to attack institutions. Both arrived in Brazil last Saturday to participate in the conservative CPAC conference in Brasília, organized by federal deputy Eduardo Bolsonaro (PSL-SP). The questioning took place at the Brasília airport, when Miller and Brant were preparing to leave the country. They were received by Bolsonaro at the Presidential Palace on Sunday. …

At the same time of the testimony, Bolsonaro made a coup-like speech before thousands of supporters in Brasília. He threatened the Supreme Court and its president, Minister Luiz Fux. Several supporters of Jair Bolsonaro are targeted by the investigation, in which the president of the PTB, Roberto Jefferson, was arrested. The Federal Police had Miller and Brant on their radar, as the panel showed, because they understand that the Bolsonarista disinformation networks operate on the same model established by Trump supporters in the United States when trying to discredit electronic voting machines. The most recent conception of this communication strategy is attributed to Steve Bannon, the guru of the Trump campaign. He was a consultant for Cambridge Analytica, involved in the scandal of using Facebook user data in the election campaign, and ran the Breitbart News website, known for disseminating disinformation. (In Portuguese.)

Brazil’s Federal Police spokeswoman, Denise Ribeiro, stressed the links among Miller, Brant and “American citizen Steve Bannon, a person pointed out as one of those responsible for the propaganda model backed by fake news used in elections.”1 Miller and Brant came to Brazil, she said,

with the intention of leveraging the use of Gettr in Brazil, which has as its proposal to restrict the control mechanisms exercised by the State, when the ideas disseminated there reach the limit of legality, in the line that separates freedom of expression from a radicalized discourse and the practice of hate crimes.

The Federal Police specifically identified the modus operandi of Bolsonaro’s supporters—the dissemination of misinformation, for example, about electronic voting machines—as “a communication strategy used in the 2016 elections in the US and credited to Steve Bannon.”

Yes, they know who they are. They knew exactly what they were up to.

In 2018, the Brazilian newspaper Folha de S.Paulo began reporting that Bannon was creating a political training school in Brazil, called the “Academia de Governo Bolsonaro.” Their sources claimed that Bannon was working with Brazilian politicians and business leaders to establish the school in a rural area near Sao Paulo. The reports also state that the school would be modeled after the “Gladiator School” that Bannon attempted to establish in Italy.

Bannon’s fingers are all over this.

Musk made Twitter safe for Brazilian fascists. He personally moderated content about the Brazilian elections. He made no effort to stop the organization of the insurrection on Twitter He claimed that Twitter had rigged the vote. And then, when the violence came, he issued the most chutzpahdik comment ever to grace social media: “I hope the people of Brazil are able to resolve this peacefully.”

Eduardo, the youngest of the Bolsonaro sons, is known as the most extremist sibling. He’s a congressman with presidential ambitions. Like his father, he avidly defends the bloody military dictatorship that ruled Brazil for 21 years. In the first year of his administration, Bolsonaro appointed his son Eduardo as Brazil’s ambassador to the US on the grounds that he was “a friend of Donald Trump’s children.”

The appointment was scuttled on the grounds that he had no other qualification, but Trump treated him as the ex officio ambassador nonetheless.

Eduardo met Steve Bannon in August 2018.

According to the Washington Post, they discussed “social media strategy.” Months later, Bannon appointed Eduardo South American representative of The Movement, Bannon’s European consortium of far-right populist movements headquartered in Brussels.

Since then, Eduardo has met MAGA luminaries and key supporters of the January 6 insurrection no less than 77 times, as documented by Pública in an excellent investigative piece. (In Portuguese.) Here are some of the people to whom he’s close:

Carol Adams, a Republican Party donor close to Donald Trump

Charlie Gerow, Republican Party strategist and president of the American Conservative Union, a conservative think tank at the center of the alliance between Trump and Bolsonaro allies. He organizes the CPACs in Brazil.

Charlie Kirk, CEO of Students for Trump and Turning Point USA.

Darren Beattie, former speech writer at Trump’s White House. (He was fired for participating in a white nationalist conference.)

Donald Trump Jr.

Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump. (They are very close to Eduardo.)

Jason Miller, senior advisor to Trump’s campaign in 2020 and founder of Gettr. Gettr has sponsored a number of events supporting Bolsonaro’s reelection in the US and in Brazil—the latter in violation of Brazilian election law.

Mark Green, who voted against the certification of Biden’s election. He was in Brazil for the CPAC and met with Bolsonaro and his ministers to discuss “electoral integrity.”2

Matt and Mercedes Schlapp. Matt has been in the news recently.

Matthew Tyrmand, of Breitbart and Veritas.

Mark Ivanyo, head of the think tank Republicans for National Renewal. The group’s primary goal is building bridges between the US and the global far right. (Ivanyo says that Hungary is “the beacon,” but in Brazil, “Eduardo is our primary partner.” Eduardo was the headline speaker at his group’s inaugural event in 2020.

Mike Lindell, the pillow guy. Eduardo went to South Dakota in August 2021 to attend a so-called cybersecurity forum organized by Mike Lindell. Bannon was there, too. Eduardo gave a speech predicting that the elections in Brazil would be fraudulent. He then met Lindell again on January 5 in Washington DC, five days before the uprising in Brasília.

Nick Luna, Trump’s former personal assistant and bodyguard.

And of course, Steve Bannon.

Pública missed a few meetings. In mid-November, Eduardo attended the America First Policy Institute’s gala at Mar-a-Lago, where he hung out with Trump and Kari Lake. Then he went to South Florida, where he had lunch with Jason Miller. Miller went to Brazil twice last year to attend Bolsonaro’s campaign events. Eduardo spoke to Bannon, who according to the Washington Post invented the term “Brazilian Spring,” this to make the pro-coup demonstrations seem more like a “wide democratic movement.” The hashtag reached Twitter’s Trending Topics many times after the election.

Bannon had declared war on Lula at Mike Lindell’s Cyber Security Symposium in Sioux City in August of 2021, as Brasilwire reported:

Eduardo was invited to take the stage and was introduced by Bannon as “the third son of Trump from the tropics.” The congressman repeated disinformation about Brazil’s electronic voting machines and presented videos of his father on motorcycle convoys with his supporters.

In an opening speech, international far-right ringleader Bannon attacked former President Lula, and claimed that Brazil’s 2022 presidential election is “the most important of all time in South America.”

Bannon said, “About 30 days before the big intermediate elections, Jair Bolsonaro will face the most dangerous leftist in the world, Lula. A criminal and communist supported by all the media here in the US, all the left-wing media. This election is the second most important in the world and the most important of all time in South America. Bolsonaro will win unless it is stolen by, guess what, the machines.”3 …

It is not the first time Bannon has spoken about Lula. Following his release from politically-motivated imprisonment in November 2019, Bannon called the former president “the biggest idol of the globalist left in the world” since the end of the Obama presidency, and that that his return to the streets will bring “huge political disturbance to Brazil.” Bannon called Lula “cynical and corrupt,” insisted that he had been corrupted by power, and warned that his return would mean the “return of corruption” to Brazil.4

Eduardo, by the way, was extremely familiar with what had happened in the US on January 6. In fact, he seems to have been involved in it. As Oliver Stuenkel wrote in The Americas Quarterly, Trump’s defeat would have been a disaster for Bolsinaro. The family was highly motivated to ensure it didn’t happen. On January 4, 2021—48 hours before the insurrection—Eduardo entered the United States for a “surprise visit” to the White House at the invitation of Ivanka Trump. Eduardo was present for the so-called War Council at the Trump International Hotel in Washington on January 5, 2021.

On the evening of January 6, Eduardo posted a photo of himself beside Pillow Guy Mike Lindell. It said, “Pleased to meet Michael Lindell, a former junkie and now a successful businessman in the US.” He also posted selfies with Jared Kushner, Ivanka Trump, Matt Schlapp, and Daniel Schneider.

During a live stream on January 6, Lindell explained the plan to “set up a committee that would give ten days where we could get the evidence” of election fraud. “The whole world is watching,” he said. Then he added, “I met with Brazil last night, the president of Brazil’s son.” (At the same meeting, we know now: Michael Flynn, Rudy Giuliani, and Sidney Powell.)

This caused alarm in Brazil, as well it should have. Below: “As if the photo were not enough, Lindell himself, live on the morning of the attack on the Capitol, confirms that he was with ‘the son of the president of Brazil’ the night before. He did a live stream towards the event that ended with deaths and depredations.”

What exactly Eduardo was doing isn’t clear, but it sure seems as if the Bolsinaros were carefully studying Trump’s attempt to steal the election.5 So the chain of events in Brazil didn’t just imitate the events that led up to January 6. The Bolsonaro family was part of January 6. Bolsonaro then replicated the experiment in Brazil, with the aid of exactly the people who performed the initial experiment on the United States.

Later on January 6, Bolsinaro senior unequivocally endorsed the insurrection at the Capitol. “I followed everything. You know I’m connected to Trump. You know my answer. Now, [there have been] a lot of fraud charges, a lot of fraud charges.” He then repeated his lies about the 2018 election in Brazil. “Mine was defrauded. I have proof of it. I should have won in the first round.” He explicitly vowed to his supporters that he would do the same thing in Brazil:

What was the problem [in the US]? Lack of trust in the vote. So there, the people voted and the mail vote was boosted because of the so-called pandemic, and some people voted three, four times, dead people voted … If we don’t have printed ballots in 2022, some means to audit the vote, we are going to have a problem worse than in the United States.6

Compare this to the way the then-head of Brazil’s Electoral Court, Justice Luís Roberto Barroso—who had been in the US as an observer of the election—responded: “Good people, regardless of ideology, don’t support barbarism. I hope the American society and institutions react with vigor to this threat to democracy.” Meanwhile, the outgoing House Speaker, Rio de Janeiro representative Rodrigo Maia, tweeted: “The invasion of the US Congress by extremists represents a desperate act by an antidemocratic tendency which lost the elections. It is ever more clear that the only path is democracy, with dialogue and respecting the Constitution.” That’s how normal people who don’t plan to steal an election respond to such a sight.

Bolsonaro was the last of the G20 leaders to recognize Biden’s victory. He waited until December 14 to congratulate him. Only Putin and Kim Jong-il took longer. From this point, every organ of the Brazilian government, Bolsonarista and non-Bolsonarista alike, feared what was coming.

The day after January 6, Eduardo retweeted Brazil’s far-right Foreign Minister Ernesto Araújo, who wrote,

One must recognize that a large part of the American people feel assaulted and betrayed by their political class and distrust the electoral process. … One must stop calling decent citizens ‘fascists’ when they demonstrate against elements of the political system or members of institutions.

Bannon was a key player in the effort to persuade Brazilians the election had been stolen. Eduardo subtitled, and shared on social media, Bannon’s speeches charging that the Brazilian election was fraudulent, and used these to legitimize the claim. The tweet below says,

Censorship looms. But make no mistake, that is the opinion of the majority abroad. The freer international press has covered our election better. If electronic voting machines were only well regarded by a few countries, now no serious country will adopt them.

Eduardo maintains close relationships with Mike Lindell, Ali Alexander (who coordinated the “Stop The Steal” movement), and Bannon himself. All of them spread, to the American public, the lie that Brazil’s presidential elections would be or were stolen. All of their lies were translated into Portuguese and fed back to the Brazilian electorate via Eduardo and his coterie.

Minutes after Bolsonaro’s defeat was announced, Bannon said on Rumble, “Bolsonaro cannot admit defeat.” (My emphasis.) So when Bannon insists the insurrection had nothing to do with him, saying, “The people down there—they’re not watching ‘Bannon War Room.’ Millions are going through the streets. It’s a self organizing protest,” he’s lying. This was anything but “self-organizing,” and yes, the people down there were watching “Bannon War Room.” To my surprise. (You’d think they’d have something better to do.)

As Pública writes,

From the production of false dossiers to lawsuits and the creation of memes with Fake News about the vote, the similarities between the actions of the two presidents before and after the elections allow us to state that it is a Playbook—a manual that follows a roadmap to erode confidence in the electoral result, keep the electorate engaged and sow the ground for actions of destabilization. (In Portuguese.)

Bolsonaro followed the Trump playbook in detail, up to the very point where he seems to have lost his nerve and fled the country. Like Trump, he insistently sowed doubt about the integrity of the electoral process. Both, early in their tenure, tried to establish inquiries into election fraud; both failed because there was none to be found. Both used allied congressmen to reinforce the lies and enhance the public’s doubts. Both flooded the zone with fantasies and memes about election fraud. Both encouraged their supporters to intimidate voters at the polls. Both toyed with the idea of delaying the election or stopping the vote count. Both refused to concede. Both refused to attend their rivals’ inaugurations. Both deplored the vote as fraudulent. Both promoted the argument that their electoral defeat was “statistically impossible.” Both filed frivolous lawsuits contesting the result. Both discussed involving the military in unseating the elected government. In both cases, their supporters endorsed the notion that the violence they had unleashed was actually committed by leftists.

Most of the key organizers and propagandists of the January 6 insurrection were involved in Brazil’s. Bannon hasn’t just been vocally amplifying the bogus claims of election fraud in Brazil. He’s been advising the Bolsonaros, meeting them at Mar-a-Lago to share tips on subverting election results. Jason Miller, too, advised Bolsinaros, which is why he was detained in Brasília.

As government buildings in Brasília were being trashed, Bannon pumped out more incitement Gettr, praising the “Brazilian freedom fighters.” He wrote, “Lula stole the election. Brazilians know that” repeatedly. This is not incidental. It is not true that no one in Brazil knows who Bannon is nor cares. Bolsonaristas seem to follow his every word. Bannon’s incitement, as the violence took place, was quite a bit like Trump’s “Mike Pence let us down” tweets. He knew exactly what effect he was having.

Bannon dedicated a significant portion of his January 9 podcast to Brazil. In the first segment, he and his guest, Matthew Tyrmand, repeated the lies about the election fraud, along with quite a few others. They claimed, for example, that the protests brought “millions” of Brazilians to the streets.

Pública analyzed all the episodes of the War Room that cited Brazil from 2021 to 2022. For months, Bannon and Tyrmand propagated false information about the Brazilian elections, in English. This was quickly translated to Portuguese and widely disseminated in Brazil. After the first round of the election, Bannon claimed it had been rigged by the Supreme Court and the Superior Electoral Court.7

Trump himself doesn’t seem to have been involved the effort to discredit the Brazilian election. He certainly provided the inspiration, however. He was closely aligned with Bolsonaro during his time in office, seeing him as a kindred spirit on matters ranging from the promotion of quack cures for Covid to harassing journalists. He counted Bolsonaro as a “great friend.”

If Trump played no special role in disseminating the Big Brazilian Lie, however, our radical wing was intimately involved. In both English and Spanish, they encouraged, justified, and then downplayed Brazil’s insurrection by spreading the charge that the election had been stolen. Tucker Carlson dedicated his opening monologue to the defense of the Bolsonarista rioters.8

Gateway Pundit, a notable source of 2020 election lies, claimed over and over that the election in Brazil was stolen. For months before the insurrection, Fox News segments were translated into Portuguese and spread on YouTube.

After the attack in Brasília, Tyrmand participated in a Twitter Space to discuss it. His co-host was Allan dos Santos, a Bolsonarista blogger on the lam from Brazilian authorities in the United States. (He’s been charged with incitement. Unlike the United States, Brazil has specific laws prohibiting lying about an election in a manner calculated to inspire violence.) Tyrmand again said that the insurrection involved “millions” of people in the “biggest demonstration in a democratic country in the history of humanity at least since the end of the Soviet Union.” (About 1,500 people were involved.) He also insisted the insurrection was “peaceful.” (Who are you going to believe, Tyrmand or your lying eyes?) He insisted it only transpired because people felt “that they would lose their democracy.” (Yes, they did—because of liars like Tyrmand.) The organizer of the Twitter Space, Mario Nawfal, explicitly and proudly compared the invasion of public buildings in Brasília to the invasion of the Capitol: “Brazil made its own on January 6.”

Similar lies were published on Breitbart, The Gateway Pundit, and on Twitter by, for example, Jack Posobiec and Charlie Kirk. (Eduardo spoke earlier this year at Turning Point USA.)9 I would have imagined no one in Brazil would care what any of them had to say. But I would have been wrong.

Elon Musk’s role deserves special mention. Musk and Bolsonaro met last May. Bolsonaro called Musk’s Twitter bid a “breath of hope,” saying he hoped Musk would end the “lies” in Twitter about his stewardship of the Amazon. He was vexed, he claimed, by Twitter’s censorship. (Under its former management, Twitter corrected his claim, for example, that Covid vaccines cause AIDS. How he imagined Musk would reconcile his desire for the “lies” to be stamped out even as the “censorship” would end is unclear.) Later, he said, “It’s the start of a relationship which I’m sure will soon end in marriage.” He added that Musk’s Twitter purchase would represent “the freedom of press that we always want and desire, total freedom, without limit.”

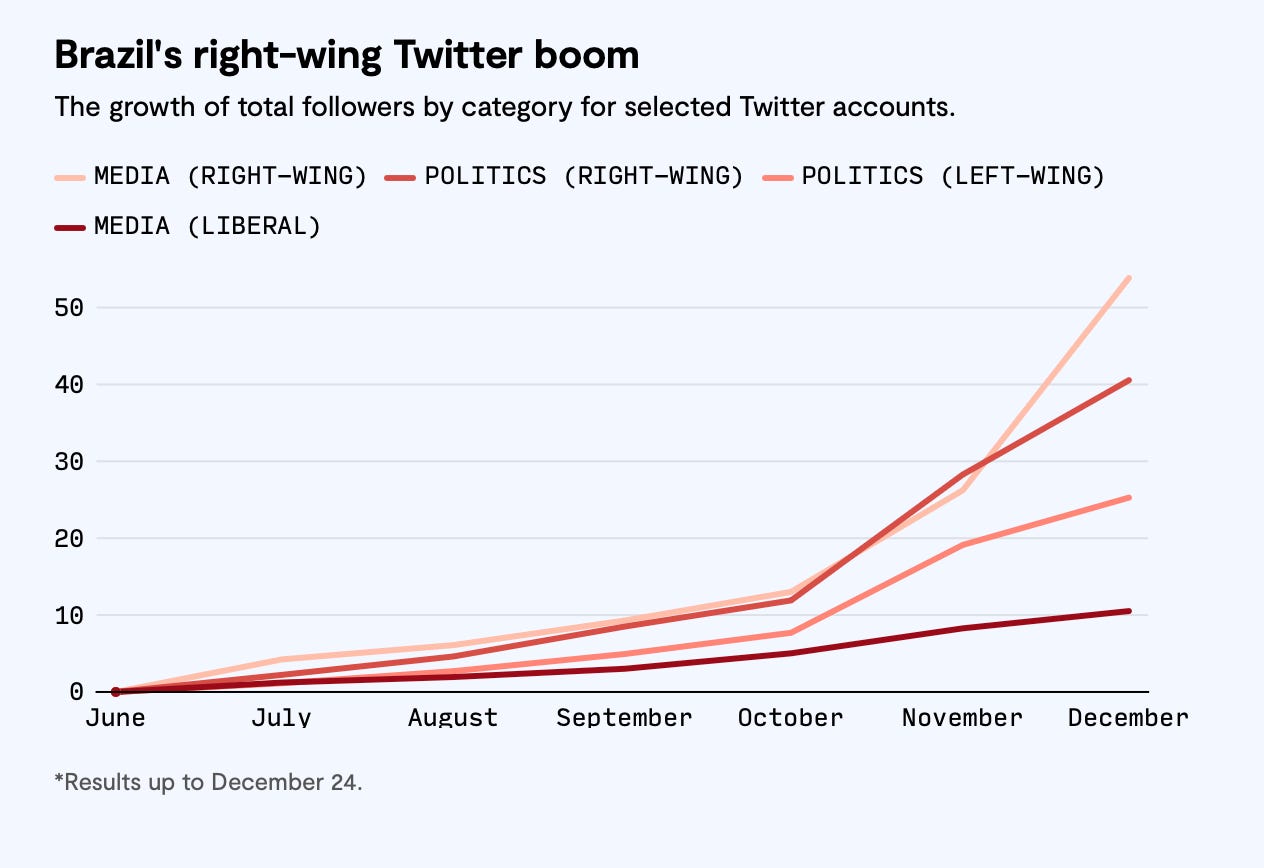

And he got his wish. As Rest of World noted, Musk’s takeover of Twitter caused Brazilians and international observers alike to worry that cutbacks in moderation would encourage Brazil’s far-right to flood the platform. With the aid of Brazilian statisticians and data experts, they therefore analyzed what had happened since Musk’s takeover. They found these concerns well-warranted:

The people flooding the platform do not seem to have been wholesome, garden-variety conservatives fretting about personal responsibility and top marginal tax rates. They cite Michele Prado, an independent researcher on the Brazilian far right:

Elon Musk has rehabilitated profiles of highly harmful extremists. This legitimizes extremist content and ... in the short term, provides content that further radicalizes people on the extreme right—people who are joining demonstrations [in front of army barracks], calling for a military coup to break with the democratic order.

It’s not “conservative,” in the Margaret-Thatcher sense, to call for a military coup. In fact, I would submit that if you’re using Twitter to call for a military coup, you should not be allowed to use Twitter. I do not believe that a robust commitment to free speech entails Elon Musk’s obligation to offer a platform to people who plan to extinguish democracy and with it, civil rights.10

Musk fired every employee in Brazil who had been responsible for moderating content. It was their job to prevent violent incitement and election denial from flooding the platform. Both promptly flooded the platform. In the months leading up to the election, social networks in Brazil were drenched in disinformation and calls (in Portuguese) to “Stop the Steal.”

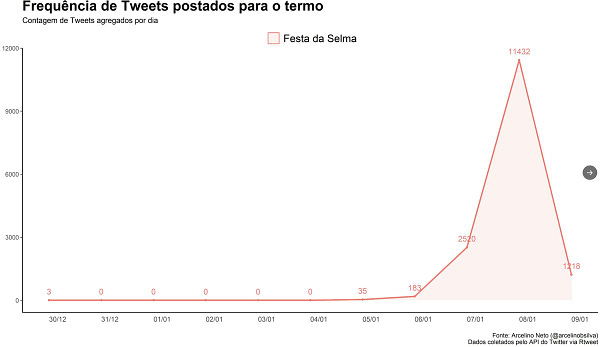

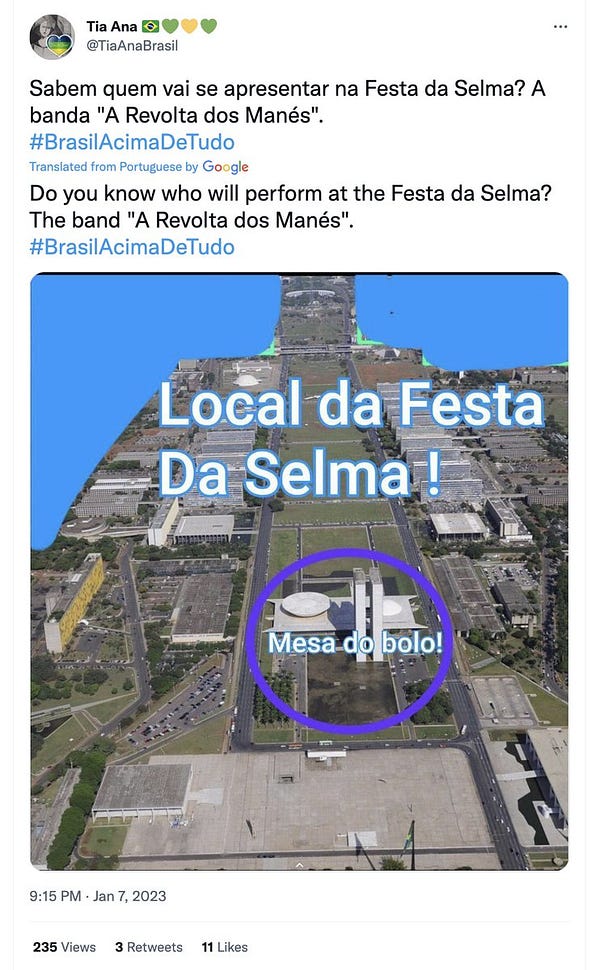

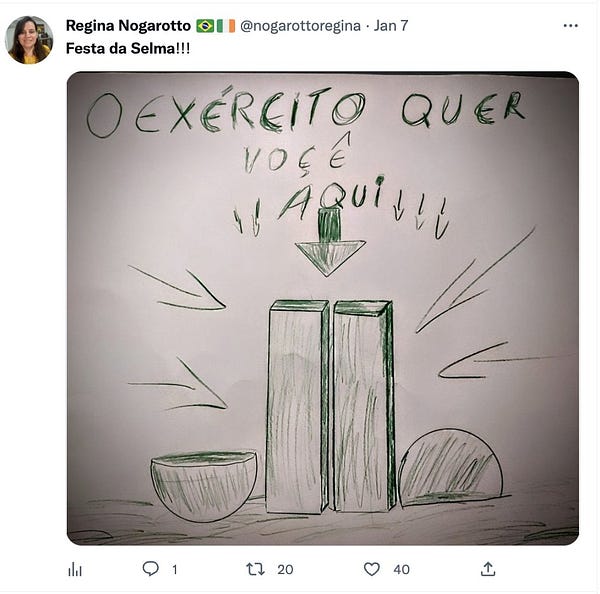

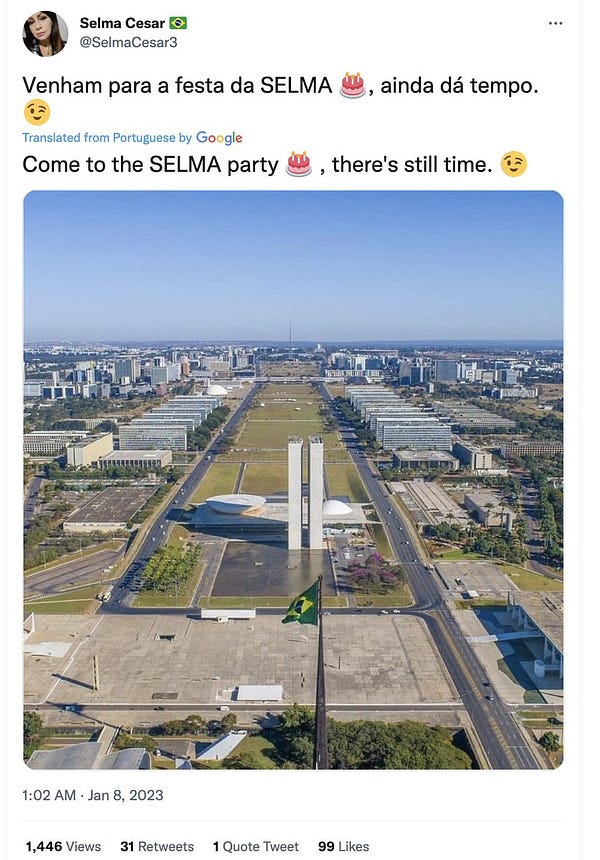

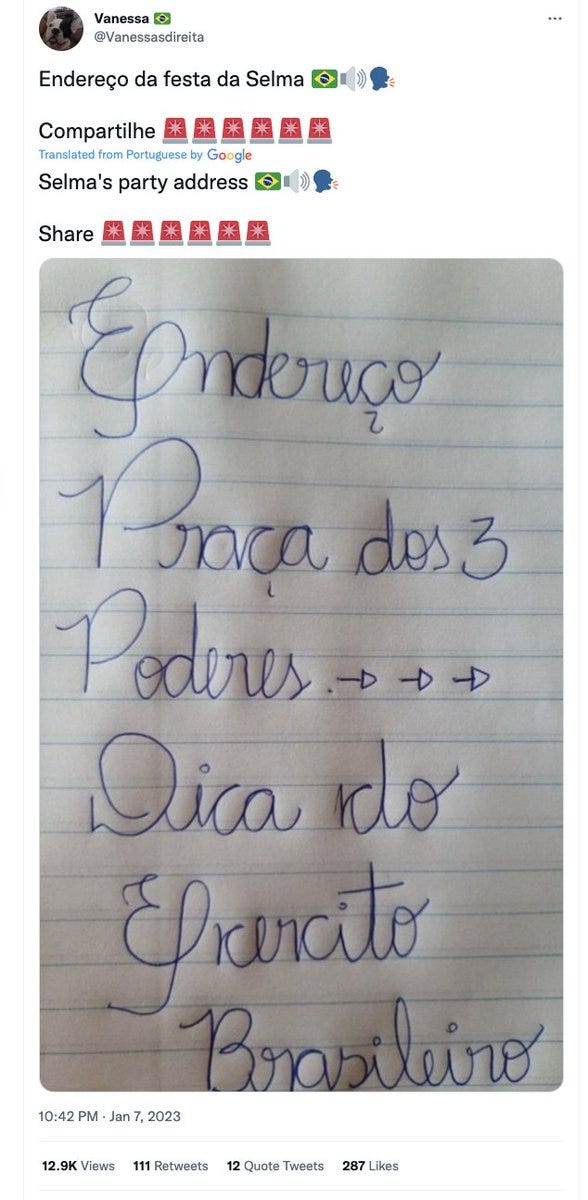

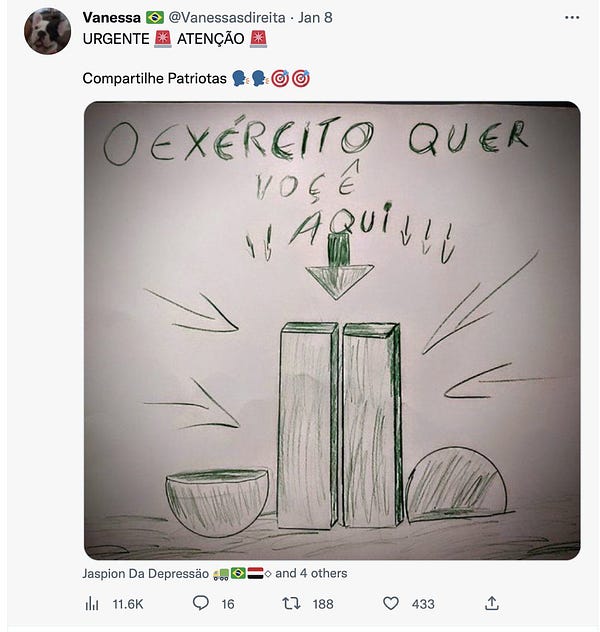

All of the violence was organized on social media: the roadblocks, the camp outside the quarters of the Brazilian Armed Forces where Bolsonaristas spent weeks baying for a coup, and the attack in itself. The insurrectionists, led by Bolsinaristas who had previously been banned, organized under the hashtag #FestadaSelma. Like the January 6 insurrection, this took place in the open. Unlike the January 6 insurrection, however, no one can claim that such a thing was previously unimaginable. Brazilians were extremely worried about the prospect, and when the day of Lula’s inauguration passed without incident, they breathed a massive and premature sigh of relief.

Musk took a personal interest in the Brazilian elections. As the Post reported:

Elon Musk has been personally moderating Twitter posts related to the Brazilian election, becoming directly involved in nuts-and-bolts operations just days after closing his US$44 billion acquisition of the social network, sources told The Post. “He is constantly calling balls and strikes,” one source close to Twitter said.

On December 3, after a long day of calling balls and strikes, Musk decided to wade into the volatile situation himself:

With this, Musk directly contributed to the febrile mood in Brazil, reinforcing every conspiracy theory Bannon and Bolsinaro had worked to sow. Musk’s willingness to believe anything he reads is, by the by, remarkable. He is someone—the only person—with access to all of Twitter’s internal files, yet he’s repeating “concerning Tweets?” It wasn’t enough for him that Twitter ceased making any effort to get lies about Brazil’s election off the platform or prevent the organization of an insurrection. Musk had to create an entirely new conspiracy theory—one based on “concerning Tweets.” Obviously, given the source, this was bound to sound credible to dimmer Brazilian insurrectionists.

To recap: Musk made Twitter safe for Brazilian fascists. He personally moderated content about the Brazilian elections. He made no effort to stop the organization of the insurrection on Twitter. He claimed that Twitter had rigged the vote. And then, when the violence came, he issued the most chutzpahdik comment ever to grace social media:

On the very day the mobs invaded Brasília, he invited Ali Alexander (organizer of the Stop the Steal rally, prominent and vocal US insurrectionist, prominent and vocal Brazilian insurrectionist) back on Twitter. He did so before Brazil’s deluded idiots had even finished proudly defecating all over the seat of their government.

Musk’s irresponsibility is a global menace, now, and by my lights, a serious one. We’ve already had a Facebook genocide. Now we’ve had two far-right insurrections, in the largest democracies in the hemisphere, inspired by lies promoted on social media.

But Twitter is hardly the only social media company to blame. There were paid ads on Facebook and Instagram in Brazil calling for a military coup. Paid ads also spread disinformation about the elections. Agência Pública found that these ads were seen more than 400,000 times:

Agência Pública identified at least 65 more ads published on Facebook and Instagram by supporters of Jair Bolsonaro who don’t accept their leaders defeat at the polls. The texts disclose undemocratic protests and defend a coup to prevent the inauguration of the president-elect, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, and have been seen at least 414,000 times since the beginning of November. Ads with coup content that propagate misinformation about the elections are not allowed by Meta’s policies. Still, only four of the publications analyzed were removed by the platform before the publication of this report. (In Portuguese.)

A lot of money was spent to purchase highly-targeted ads on Facebook and Instagram that seeded lies about the election. Who purchased those ads? Who advised them about how to target their audience? Accepting such ads is against Meta’s policies. Shouldn’t someone sue them?

The policies social media companies adopt in the face of this trend matter enormously to the future of democracy. This is now proven, not hypothetical. Musk’s approach—Popper’s paradox be damned—is grossly unsuitable for a private platform that offers algorithmically-accelerated, anonymized, no-cost speech.11 We’ve seen the consequences of it; we’ve seen them repeatedly. They’re terrible.

Beyond the role that Americans played in both uprisings, I wonder to what extent social media, inherently, causes people to behave this way. Does it, by its nature, give rise to a predictable and dismal cascade of events involving political polarization and radicalization, fake news, and a violent challenge to elections? If so, we need to think hard about this, because that won’t be the last insurrection we see. What do we do if the epistemological chaos characteristic of the modern information environment is incompatible with democracy? What’s more important to us—ordered liberty, or Twitter?

So what will happen now in Brazil? The crackdown on the Bolsonaristas could be quite repressive. The US managed to get through this experience without descending immediately into authoritarianism, but this doesn’t mean Brazil can do it. Brazil’s creepy Supreme Court, in its zeal to protect Brazil from Bolsonaro, has of late been throwing more people in jail without due process than makes sense. Did Bannon think for even a second about the risk he was creating for ordinary Brazilians whose crime was being dumb enough to believe his lies?

What were they thinking, playing around with this in Brazil? They have no business there. The American media has pointed out insistently that the Brazilian insurrection occurred almost two years to the day after the American insurrection, but it’s more significant that January 8 is the fifty-year anniversary of the São Bento massacre, one of the bloodiest days under Brazil’s military dictatorship.

We have an obligation to help Brazil recover from this. These are our cretins, and we’ve failed to control them. We shouldn’t allow this to fade from our headlines. American journalists should work with Brazilian journalists and investigators to understand exactly what happened.

They should ask the following questions, too: What’s going on in Florida? Why has Bolsinaro taken up residence there? Why is the former head of security for Brasília, Anderson Torres, vacationing in Florida? (He’s been fired because of the police’s dereliction of duty in Brasília, and rightly so.) What else do we know about Eduardo’s activities? Who financed the attack in Brasília? Who paid for all those the buses? Who bought those ads on Facebook?

We need to think about a moral and legal architecture for social media that makes sense. We simply must prevent our citizens from trying to topple democratically-elected governments abroad. It’s absurd and outrageous that we now have a group of Americans who fly around the world trying to violently overthrow the governments of our allies.

There’s precedent for charging US citizens who foment coups overseas. We’ve successfully brought charges against Americans for trying to overthrow the Gambian government, for example. Our legislation isn’t far from being what we need to contain this problem. (If the House weren’t being run by insurrectionists right now, we could pass it tomorrow.)

We should cooperate fully with Brazilian investigators, and if they ask us to extradite Americans for violating Brazilian law, we should. Americans, for the most part, don’t know how much they should fear a coup. Brazilians do. If we can’t find the mettle to prosecute our coup-plotters, maybe they’ll do it for us.12

We should have prosecuted these people already for their roles in our own insurrection. Garland’s delay in doing so is inexcusable, and it’s had tragic consequences. These people aren’t just threatening the United States, but every democracy, at a time of great global instability and risk. The United States is now—rightly—viewed as a threat to democracy, even among our allies, and we will be until we put these people behind bars.13

I found this in a Portuguese source, and forgot to copy the link to it. Now I can’t remember where I found it, and because I don’t speak Portuguese, don’t know how to search for it. I’ve been looking for an hour. I’ll keep looking, and I’ll update this when I find it.

Green: “Over the last two months, I’ve heard from countless constituents who have no confidence in the outcome of the presidential election in certain states. And who can blame them? I tried to sound the alarms for nearly a year in House Homeland Security Committee and Oversight Committee hearings that the increase in mail-in balloting and last-minute changes to election laws could lead to confusion, fraud, and distrust. Sadly, those warnings were not heeded.”

At the time, polls showed Lula ahead of Bolsonaro by nearly 20 points.

It’s hardly as if it went away. The going theory in Brazil seems to be that Bolsonaro decamped to Florida to evade prosecution for corruption, or worse. (There are also persistent stories of Bolsonaro’s involvement with death squads. I’m not in Brazil; I couldn’t possibly say if those are true.)

Bolsonaro’s argument is that electronic voting machines cannot be trusted and Brazil needs print ballot to prevent fraud. Absolutely no one who understands how the machines work agrees with him. Brazil’s electronic voting system is “a model for the nations of the hemisphere and the world,” according to the State Department.

Every national and international observer from the Federal Court of Auditors to the Organization of American States to the Carter Center has testified that the elections were transparent and fair.

What is wrong with him? What is Tucker Carlson’s motivation for supporting Vladimir Putin, Victor Orbán, Brazilian insurrectionists, anti-vaxxers, and every other indecent cause on earth? Why is he unerringly drawn to these causes? His viewers don’t care about Brazil. He doesn’t need to have an opinion about this at all, no less this one. Seriously, what’s up with this? I’m aware that he’s not unprecedented, but it’s fair to say that not since Father Coughlin has there been a figure like Tucker Carlson in American life. I wish journalists would ask this question with more seriousness. I wish Fox would ask itself this question with more seriousness. This is a deeply sinister figure, and someone needs to figure out why he’s doing this.

If you take the Twitter files seriously, you will believe that the de-amplification of Posobiec by Musk’s predecessors is a scandal. I find it more scandalous that he’s allowed to be on Twitter at all, given his record of inciting two violent insurrections against democratically-elected governments, one of them our own.

Not that Musk has any kind of commitment to free speech. What he’s said, in this regard, is obviously horseshit.

For those who need a refresher, here is Karl Popper’s argument, from The Open Society and its Enemies:

Less well known [than other paradoxes] is the paradox of tolerance: Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. … In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right to suppress them if necessary even by force; for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to rational argument, because it is deceptive, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists or pistols. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, in the same way as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or to the revival of the slave trade, as criminal.

We should also ask whether Russia played a role in this. Bolsonaro was one of Putin’s few allies. Despite being asked by Washington urged to cancel his trip to meet Putin last February, Bolsonaro not only visited him, but declared himself “in solidarity with Russia.” Brazil voted against a resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the UN General Assembly. Bolsonaro condemned the economic sanctions against Russia last July. Brazil abstained from a UN draft Council resolution condemning Russia’s announcement that it had annexed Ukrainian territories. Russia had good reason to hope for Bolsonaro’s success.

See, for example, this editorial in Japan’s Asahi Shimbun:

… The United States also experienced a mob attack on the Capitol Building two years ago. Investigations and indictments are still under way, and the extent of involvement by former President Donald Trump and the Republican leadership remains to be fully clarified.

But one thing is certain. The movement in Brazil to reject the results of its own presidential election was influenced by the US Capitol invasion of Jan. 6 , 2021. In that sense, the United States is also very much to blame for what occurred there. … Rifts in society are widening in the United States and Brazil, while other nations are leaning toward authoritarianism. We believe it is one of Japan’s tasks to urge them all to reassess the value of democracy.