Read Part I, first. This won’t make sense otherwise.

When we left off in Part II, Marine Le Pen had expelled her father from the party, and he had disowned her, accusing her of “sawing off the branch on which she sits.” Soon, another branch of the family—Marion Maréchal—will cross-pollinate with a local shrub.

This essay written by my father, David Berlinski, is the perfect introduction to Eric Zemmour. —Claire

“France has not Said its Last Word”

Ed. Rubempré, September 2021

David Berlinski, Paris

Éric Zemmour is a French political journalist by profession, a long-standing contributor to Le Figaro; and if he is known at all in the United States, he is known chiefly for being well-known in France. In France, he is known for being rather like Donald Trump—striking evidence that neither country understands the other. The resemblance, if it exists at all, is sentimental. Zemmour is as lean as Trump is fat, vulpine in aspect, so much so that were he to be seen exiting a chicken coop, no one would be surprised.

It has been Zemmour’s presence on the new French television station, Cnews, that has promoted him up from scribbledom.1 Arrayed against a number of croaking rabâcheurs, he talked over them when necessary, and, when not, talked endlessly; in his moments of repose, he smiled, grimaced, chuckled, shrugged, snickered, guffawed, and, from time to time, held his hands up to the heavens in a gesture suggesting it was all too much to bear. He proved himself a master of French debate. Aucun sujet ne lui fait peur, Manuel Bompard remarked.2 No subject frightened him. True enough. As he caused a stir, he gained a following, and, by a process akin to transubstantiation, managed to appear in the French presidential race the moment he disappeared from Cnews.

French presidential elections are held in two stages. If in the first round no candidate wins an absolute majority, the two leading candidates face one another in the second. The scramble for pole position is now underway, with even Anne Hidalgo, the mayor of Paris, convinced that by continuing to open her mouth, she is bound to attract the sort of late summer lightning generally seen flickering over hot air. With the exception of Zemmour, the candidates have all declared that if France does not yet know what she wants, they know what she needs. Zemmour has remained undeclared and unreformed, and by saying out loud what many French politicians would not dare say at all, he has made himself the cynosure of every media eye.

He has a genius for publicity. When offered a high-powered French sniper’s rifle for inspection, he promptly pointed it at a number of journalists. The junior minister of the interior, Marlène Schiappa, eagerly took the bait in the expectation, or the hope, that shortly she would be able to swallow it, whereupon Zemmour denounced her as an imbecile. It was a conclusion to which the French had independently given their assent. Marlène Schiappa is, after all, the author of Lettres à mon utérus.

Zemmour’s fondness for forest fires has done him no harm. The most recent Harris poll has him pegged at 17 percent of likely voters. No candidate has ever done so well in so short a time, remarked Antoine Gautier, the head of research at Harris Interactive.3 That what goes up may well come down is a political principle that, for the moment, seems to have escaped Gautier’s notice. Dominique Strauss Kahn was doing very well in public opinion polls until he was discovered investing himself heavily in room service at a New York hotel.4

If nothing else, Zemmour’s ascendance has left Marine Le Pen gasping for electoral oxygen. In an interview with Boulevard Voltaire, Zemmour suggested that Le Pen had foundered because she failed to see that whenever he spoke, civilization itself was at issue and thus at stake. Madame Le Pen acquired a stricken look. And no wonder. She had for years made every effort to purge her party, le Rassemblement National, of the least trace of anti-Semitism.5 Her commitment to Israel was said to be profound. That she now found herself outflanked by a French-born Algerian Jew may well have persuaded her to reconsider the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

It would have persuaded me.

Whatever the lessons Zemmour means to impart to Madame Le Pen, Emmanuel Macron is shortly to learn them, too. “We are the two poles of a real debate,” Zemmour has said, adding again that what is at issue is a clash of civilizations.6 These are exciting words, suggesting, as they do, Ezekiel 38–39, or, at any rate, something more exciting than questions about French gasoline prices, an issue last seen exercising the Gilets Jaunes and no one else. In Le Suicide Français (The French Suicide), Zemmour was notably pessimistic about the whole business, as the title might suggest; but he has since perked up considerably, and in his most recent book, La France n’a pas dit son dernier mot (France Hasn’t Said its Last Word), he indicated that a country capable of electing him to the presidency might not be quite so tempted by suicide as previously he had supposed.

Le Suicide Français was a notable bestseller in France. It made Zemmour’s reputation as a man of declarative fearlessness. Multiculturalism, women’s rights, homosexuality, American historians, the young, the fat, no-fault divorce, 1968, dowdy women, the Rolling Stones, hairy transsexuals, the Centre Pompidou, affirmative action, the feminization of French society? He was opposed to them all, professional French women especially. At his public trials, they had it in for him and he has it in for them:

The president of the court is a woman; so is the prosecutor. So are most of my accusers’ lawyers. Under their black robes, which is really a prestigious uniform of another era, they wear mediocre clothes, the fabrics tired, their hair done in a hurry, their makeup done without care; everything in their silhouette, their attitudes, their absence of elegance, gives off a je-ne-sais-quoi air of negligence, carelessness, and lack of taste. One sees at a glance that members of these professions have tumbled down the rungs of the social ladder.7

On the other hand, Zemmour has no political experience whatsoever, circumstances that may well appeal to the French before he assumes power, but are likely to dismay them if he does. The point has not gone unremarked:

Justice, immigration, secularism, the authority of the State, equality between men and women ... On all these subjects, the French are familiar with Éric Zemmour's thoughts; and Zemmour, in any case, could soon leave off being a polemicist in order to devote himself to the presidential campaign. But what about his positions on the economy?

His positions on the economy? There is this:

… the common thread of his positions, if he is a candidate, is to defend the interests of France and the French. This means regaining the country’s sovereignty and economic pride.8

These are words, Trumpian in tone, but détromper in effect, if only because their connection to any coherent economic policy is hard to discern.

Never mind. Éric Zemmour is not about to address the niceties of international trade or the doctrine of competitive advantage, and besides hinting broadly that what was good enough for Jean-Baptiste Colbert is good enough for him, he has hinted nothing at all. The sources of his appeal are otherwise.

If so, otherwhere? It can hardly be said that Zemmour has imposed himself on the French by means of his personal magnetism. He has none. Among his supporters, he appears, although smiling grandly, distinctively uneasy, almost as if he is prepared by racial memory to see a weapon in their outstretched hands. Why, then, Zemmour? It is a question that has occupied all of the gabbling French talk shows, and for once the gabble seems to have converged on a consensus. It is because alone among the candidates, he is prepared to talk of matters of deep concern to the French, their concerns so deep that if they are in plain sight, they remain forbidden to plain speech.

On Islam, Zemmour is unyielding. There is an irremediable clash between French and Islamic civilizations. Should they find themselves in the same room, one of them must get out. Just recently, Zemmour debated Jean-Luc Mélenchon on French television. Mélenchon is a cultivated, well-read man. When confronted by Zemmour’s declaration that either we get rid of them or they get rid of us, he responded with the by-now expected objurgation: vous êtes un raciste, a gesture as useful as that of a peacock in spreading its tail feathers before a boa constrictor. The solution to the problems posed by Islam in France, Mélenchon argued, was a form of creolization, the promotion of scattered pidgins into a new national language. Zemmour needed only to observe that so far as he was concerned, pidgins were pigeons, and that, in any case, the French themselves showed no very great eagerness to see their original language disappear in favor of a Gallo-Islamic monstrosity.

When not relieving himself of his animadversions in debate, Zemmour repairs to the French classics to make the case that Islam is just no good, appealing especially to Claude Lévi-Strauss:

[Islam is a] great religion which is based less on evidence of revelation than on an inability to establish causal connections in the external world. In the face of the universal benevolence of Buddhism, or the Christian desire for dialogue, Muslim intolerance takes on an unconscious form in those who are guilty of it; if they are not always interested in brutally getting others to share their truth, they are nevertheless … incapable of supporting the existence of others as others. The only way for them to protect themselves from doubt and humiliation is through their annihilation, witnesses of another faith and another way of life.9

When in 2002 Levi-Strauss was asked to reassess this paragraph, he could do no better than to appeal to Michel Houellebecq, a form of reciprocal reinforcement that rather suggests a building large as the Taj Mahal mounted on two toothpicks:

I said in Les Tristes Tropiques what I thought of Islam. Although expressed in a more temperate language, it is not far from what Houellebecq is saying today … 10

The appeal to Houellebecq was prophetic. There is a strong family resemblance between Zemmour and Houellebecq. Having both been kidnapped at birth by gypsies, the hypothesis that each is the other’s twin cannot easily be dismissed.

Still, Zemmour has managed to suggest a point of incoherence in the very idea of multiculturalism. If cultures are distinct, they can be mixed, as they were in Cairo or Istanbul under the Ottomans, but they cannot be merged; and if they are not distinct, what point remains in trying to merge them?11 Islam, in Zemmour’s view, stands opposed to classical French values, in particular; and to the long traditions of European thought in general. It is a great totalizing force; uninterested in accommodation, it demands submission; and where it has taken root in French life, it acts as an infection beyond antibiotic therapy, the very many Muslim enclaves dark, hooded, violent, criminal, isolated, fanatical, intolerant, drug-obsessed, misogynistic, opposed entirely to Republican values, and amenable only to force if they are amenable to anything at all.

Distinct enough?

Are the scattered Muslim communities in France violent, criminal, and generally opposed to French republican values? Some of them, sure.12 Are French efforts at assimilation weak, disorganized, fatuous, and largely ineffective? That, too. If this is all very worrying, Zemmour is prepared to explain how very worrying it all is:

Not a day without theft, rape, assault in the street or in the subway. Not a day without its countless gratuitous assaults. Not a day without its crime. Not a day without her police station attacked, her school burned down, her police officers assaulted, targeted by mortar fire, her firefighters stoned, her doctors threatened, her teachers insulted, her young French women raped, her teenagers injured, her drug traffickers arrested and released, her RER passengers molested, robbed, her schoolboys contemned as dirty French, her old men robbed, her old women brutalized and murdered.13

À chaque jour suffit sa peine, as the French rapper Nessbeal remarked.14

It comes as a surprise to learn that the French homicide rate is 1.3 per 100,000.15 A homicide rate of 1 per 100,000 functions as something like a standard candle measuring the lowest possible homicide rate.16 The US national homicide rate is four times greater on average than the French, and more than ten times greater in various southern cities. In 2021, the New Orleans homicide rate stood at 17.5 per 100,000. These are facts that have provoked Zemmour to the contemplation of counter-facts—contrefaits, first cousins, of course, to counterfeits. “Cities like Grenoble,” Zemmour writes, “are compared by their citizens to Chicago with respect to crime.”17 The Grenoble homicide rate is 2.83 per 100,000; the Chicago homicide rate, 18.26. Whether the inhabitants of Grenoble were conveying their regret at not doing better at home or expressing their admiration for a job well done in Chicago is not entirely clear.

What is very curious in all this is the deep community of interests between France’s Islam and Zemmour’s France. Zemmour is in favor of the family; he is opposed to divorce; homosexuality, sexual deviance of any sort: He regards transsexualism with the undisguised horror a man discovering a pit viper in his toilet bowl, and at the worst possible moment, too. Zemmour is in favor of the heavy hand of decorum; he is an elitist in art, culture, cuisine, and literature; he is a Bonapartist and a Gaullist; and, in all this, what point of principle separates him from Islamic thought? He does not wish to be ruled by mullahs: fair enough; but he is a man enough of the world to understand that he must be ruled, and so the point at issue is an embarrassment of choices. Zemmour has read Freud. He quite understands that no society can endure that does not limit the instinctual desires of mankind. He is appalled by films such as Les Valseuses. He is in favor of female modesty, good manners, decorum, the elegance and refinement of life, the arts, fine dining, and the sense of virility that affords a man the pleasant sense that, Thank God, he was not born a woman.

Why Monsieur, any Muslim cleric in France might well respond, so are we.18

In all this, Zemmour is good fun. It is impossible to resist his pleasure in the headline Libération assigned his profile: Bite Génération.19 His discussion of a meeting he held with Marine le Pen is a masterpiece of controlled malice, Madame le Pen, her foot in a cast owing to a fall, emerging from their rencontre as a crippled lummox.

The fun goes only so far. It is one thing to read Zemmour’s endorsement of virility, the more so since in combat with a flea, the ensuing order of precedence would be difficult to predict; but it is quite another to read Zemmour’s assessment of Vichy. It is a subject that demands another level of moral seriousness.

Under the Vichy regime, roughly 75,000 Jews were deported from France to their death in in the German-occupied east. Of these, one third were French citizens. Two hundred thousand Jews survived, the majority French citizens. In Holland and in Belgium, proportions were reversed. The facts, if incontestable, are hardly a source of pride.

It is for precisely this reason that Vichy officials and their apologists were concerned to embed the facts in a narrative that did them more credit than the facts might suggest. It is a narrative with a familiar shape: Mass murder does not offer its apologists a great many rhetorical luxuries. If French officials who were not otherwise disposed to harm a soul found themselves presiding over the deportation of foreign Jews, why, this was only because they were forced to do so by the Germans. They accepted what they could not change, but shortly thereafter they challenged what they could not accept. Vichy officials became the shield behind which French Jews gathered. “I did all I could,” Pierre Laval argued at his postwar trial, “considering the fact that my first duty was to my fellow-countrymen of Jewish extraction whose interests I could not sacrifice.”

Writing in the revised and last edition of his 1961 treatise, The Destruction of the European Jews, Raul Hilberg accepted Laval’s argument:

The foreign Jews and immigrants were abandoned and an effort was made to protect the native Jews. To some extent, that strategy met with success. By giving up a part, most of the whole was saved.20

Until the publication of Robert Paxton’s two studies, Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order, 1940-1944, and Vichy France and the Jews (written with Michael Marrus), the Vichy narrative seemed to do justice to the facts, and in the best possible way: the facts were acknowledged, the state excused.21

This has now changed. Unlike Hilberg, Paxton and Marrus had studied the French archives. The narrative, they determined, was wrong in most aspects, and where it was not wrong, misleading. Neither the French nor the German archives revealed a strategy to save French Jews: No shield protected them; and no Vichy official was ever heard echoing General Mario Roatta, who, when asked to turn over Jews to the Germans in the Italian-occupied portion of Croatia, declared that to do so would be “incompatible with the honor of the Italian Army.”22 There were some things that even an ardent fascist would not do.

Vichy France was a profoundly anti-Semitic state, and in its legal restrictions on Jewish life, it drew no distinction between Jews in France and French Jews.23 Vichy copied Nazi laws and ordinances—designating Jews as an underclass, banning them from the army, press, commerce, and industry; depriving them of the right to hold public office; restricting, even, the hours they could be seen in public. The deportation of foreign Jews was not forced upon Vichy by the Germans. Quite the contrary. It was a French initiative, the Germans themselves somewhat surprised to have encountered a European satrap so entirely prepared to appreciate the seriousness of the Jewish problem.24 French officials understood that with the deportation of foreign-born Jews complete, they would be obliged to send French Jews to their death. The Final Solution meant the destruction of every last Jew in Europe; in the end, it meant the destruction of every last Jew on earth.

French officials understood this, too.

Zemmour has read Paxton and this leaves him in the difficult position of endeavoring to show that while Paxton may have been correct in detail—the dead were, after all, dead—he was incorrect in some larger moral calculus to which Zemmour has been given access. While we are obsessed by “les préoccupations humanitaires et l’extermination des juifs”—humanitarian concerns and the extermination of the Jews—the French under Vichy were occupied by “more prosaic concerns,” and if they happened to notice their neighbors being deported in cattle cars, they very reasonably came to the conclusion that deportation was, in fact, an undertaking in which young people were sent to Germany for a spell of healthy outdoor labor under the auspices of the Service du Travail Obligatoire, or STO.

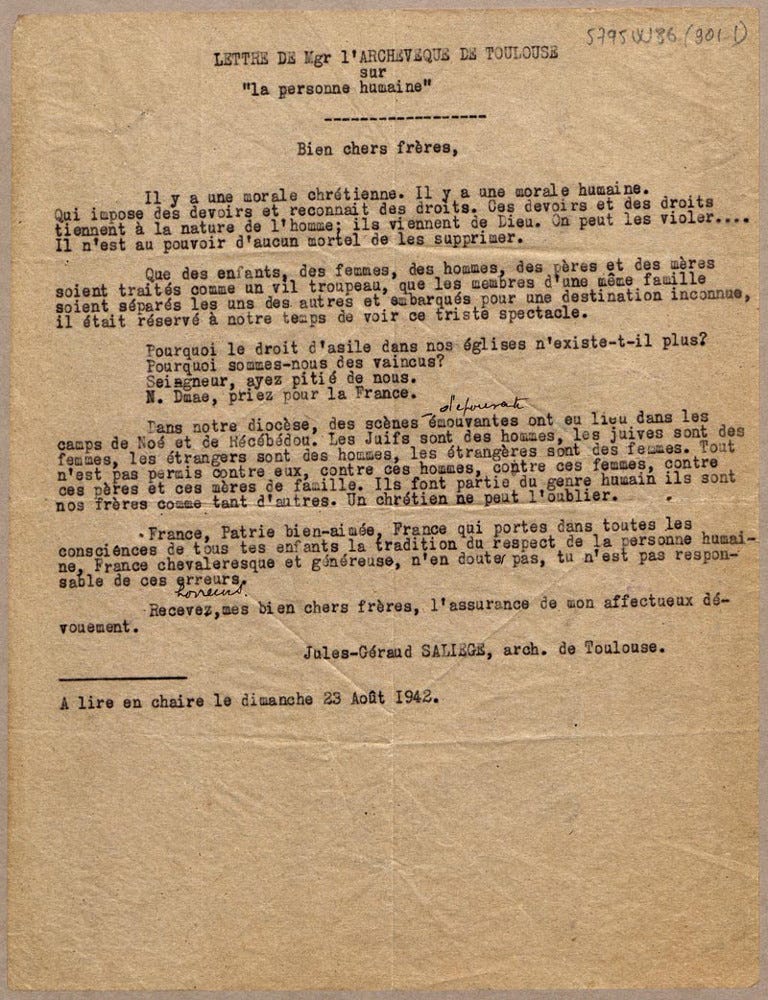

It is not entirely obvious that in our time, anyone is much obsessed by the extermination of European Jewry. The world has taken the Holocaust in its stride, no doubt following Raymond Aron, who, Zemmour writes, “exhorted his co-religionists to reject ‘the obsession with memory.’”25 Whatever the prosaic concerns of the French under Vichy, they knew very well what deportation entailed. On the 23rd of August, 1942, Monsignor Jules-Géraud Saliège delivered a pastoral letter to his congregation.26 It is a noble document. His concerns proving somewhat less prosaic than most, Monsignor Saliège noticed what was underneath his nose: France was deporting men, women and children to an unknown destination. Saliège was under no illusions about just who these people were. And no illusions about where they were going. Tout n’est pas permis contre eux—not everything is permitted against them, he warned. On the 30th of August, Monsignor Pierre-Marie Théas, the Bishop of Montauban, remarked in his own pastoral letter that the anti-Semitic measures in force throughout France were an insult to human dignity, a violation of the most sacred rights of the individual and the family.27 This does not sound as if the French were misinformed about the meaning of deportation.

Neither were Vichy officials.28

In his discussion of the now-standard historical account of Vichy, Zemmour offers neither facts that deserve to be better known nor arguments that deserve to be better heard. He is in his historical inquiries desultory. The gravamen of his concerns is elsewhere. The Jews whom the French sent to their death, Zemmour believes, were sent to their death because they were not French enough.29 Citizenship is no longer at issue. A sinister new moral calculus has come into play. In his desire to champion being French beyond the possibility of denial or defection, Zemmour has come close to excusing mass murder. It is something that he seems to sense. In a recent television appearance with Ruth Elkrief, he refused to discuss Vichy further on the grounds that he had said enough. In this, he was correct.

Robert Paxton is another matter. He looms large in Zemmour’s thoughts and he is about as distractible as a Rottweiler. In Le Suicide Français, Zemmour drew a distinction between assimilation and multiculturalism. He is in favor of the first, contemptuous of the second. With Paxton, it is the other way around. The French have long demanded assimilation of its Jews, the demand itself going back to Clermont-Tonnerre’s address to the National Assembly in 1789: Il faut tout refuser aux Juifs comme nation et tout accorder aux Juifs comme individus—everything for the Jews as individuals, nothing for their people. If this is an especially astringent form of assimilation, it is one that Zemmour is prepared manfully to swallow. There is, he writes, after all, a

radical difference in point of view between Xavier Vallat, a Maurrasian30 anti-Semite, who tolerated only assimilated Jews in the manner of Swann in Proust, and [Heinrich] Himmler, who judged assimilated Jews to be the worst kind of Jews because their Jewishness could not easily be revealed.

It cannot be said that this remark comprises an entirely satisfactory defense of Xavier Vallat. It is no great achievement to be morally superior to Heinrich Himmler, and, indeed, the position is available to the common cockroach. Nor is the radical difference to which Zemmour appeals quite as radical as he suggests. In his autobiography, Xavier Vallat, who was, after all, the Commissioner-General for Jewish Questions under Vichy, remarked that he found Jews “parfaitement supportable à dose homéopathique”—perfectly acceptable in homeopathic doses.31

Let me see. At 6X under the Hahnemann C scale, the relevant homeopathic dilution would be one part per million. The population of France in 1940 was roughly forty million. M. Vallat was thus prepared to tolerate forty Jews on French soil. This cannot be considered expansive in its generosity. The homeopathic scale goes up to 10X. At that dilution, Vallat would have been hard pressed to find a single Jew, thus prompting the question what he proposed to do with the three hundred thousand Jews contaminating the French homeopathic state?

Just what he did, one imagines.

During the press of his wartime duties, Vallat was rather less whimsical:

The Jew is not only an unassimilable foreigner, whose implantation tends to form a state within the state; he is also, by temperament, a foreigner who wants to dominate and who tends to create, with his kin, a super state within the state.

Then there is Justice Minister Barthélemy, another great sniffer of ethnic distinctions:

[The Jews] have refused for centuries to melt into the French community.

Given his ethnic character, his reactions, the Jew is not assimilable. So the regime considers that he must be kept apart from the French community.32

If this is the company Zemmour prefers to keep, need it be said that they would have preferred not to keep his?

Assimilation à la français—Zemmour’s vulgar phrase—was always a heavy imposition. French Jews had never been completely assimilated into French life, since what was required was a state of assimilation so perfect that it extended backwards by five generations and thereafter so complete that every trace of Jewishness was wiped from the Jewish face.33 Assimilation, unlike citizenship, is a matter of degree, and in the eyes of Vichy officials, Jews in France, whatever their citizenship, could decrease but never obliterate the distance between themselves and the French.

The historical experience of Jews both in France and in Germany revealed the demand for assimilation to be what it was all along: impossible to meet and repugnant to impose. To the outsider, French or German Jews might have seemed perfectly assimilated, but to the racial Feinschmecker, no degree of assimilation was satisfactory. To be a Jew was to be a Jew necessarily. The Jews of both France and Germany understood this.34

Years later, some German Jews had their revenge. Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem is in very large part an attack on Adolf Eichmann for the clumsiness of his German diction and the inadequacies of his Kantian scholarship, deficiencies, needless to say, to which a real German—someone, in fact, rather like Hannah Arendt herself—would not be liable.35 To the end of her days, Arendt was unable fully to compass that Eichmann was a real German and that to the end of his days, Adolf Eichmann, were the matter put to him, would have regarded Hannah Arendt as a real Jew, her grasp of Kant notwithstanding. There it is: the fatal delusion among French and German Jews: that they were French or Germans because they spoke better French or German than their killers.

Anxieties that have affected so many others have affected Eric Zemmour. He is what he seems, an outsider forever burrowing into the center of things but forever consumed by the anxiety that he is not burrowing far enough.36 It is hardly a surprise that he feels obliged to suggest that one hundred years after his innocence was decisively established, Alfred Dreyfus may well have been guilty.37 If in this he believes that he is satisfying the ghost of Charles Maurras, still grumbling in the hereafter about la revanche de Dreyfus, he is mistaken. Both French and German Jews were consumed almost to the point of madness by the wish to demonstrate that they were French or German enough. It did them no good.

Zemmour cannot let the whole business go and in a rhetorical declaration that any psychologist would recognize as a form of projection, he has complained that “millions of people live here in France, but don’t want to live à la français.” I am one of them, and although I am prepared, when all Paris goes mad with grief, to accept residence in the Panthéon, it will be as an American and a Jew, the terms of exile. Nothing better, so far as I am concerned, and certainly nothing less.

The demand placed on strangers that they had best get busy and assimilate themselves is an idea in service to the much larger idea of the nation-state. The distinction between the two is crucial. The state is the largest administrative unit within a particular geographical region. The nation is another concept entirely. It belongs to the mythical orders of mankind. One becomes a citizen of a state; one is assimilated to a nation.

There is something like the French nation, an imaginary brotherhood extending, at least, to the throat of the Merovingian empire, a collocation of continuities in speech, dress, attitudes, manners, habits, religion, and psychology. No one doubts this. To be French and to be Chinese are two quite different things. And, indeed, one might define the French nation as the last common ancestor of all living Frenchmen together with all of his or her descendants, the dead as well as the living a part of one mystical brotherhood. The moment an effort is made to make precise the very idea of the French nation it becomes plain that those satisfying the definition of French nationality and those satisfying the definition of French citizenship are not one and the same. French school books begin with the words Nos ancêtres les Gaulois. Neither my ancestors nor Zemmour’s were Gauls. I would bet my life on it.

Jews in France were forced to do as much under Vichy.

They lost the bet and paid with their lives.

The idea of assimilation is an irrelevance because the nation into which one is assimilating is an illusion. If defined carefully, as I have just defined it, it follows that hardly anyone is a French national. Too many centuries in which one group after the other washed across the ever-shifting borders of Europe have made that an impossibility. If defined loosely as a mystical order, as when the Nazis spoke of the entirely imaginary Aryan nation, it follows that no one is an Aryan (or a Frenchmen) since there are no public criteria for membership. The most perceptive observers of Nazi Germany recognized that in the end, only the SS would be pure enough to bear the burden of Nazi ideology, and even then, not entirely so. The Nation belongs to the mythical orders of mankind where it occupies a profoundly dangerous place.38

Every human being keeps locked within certain forbidden thoughts. What is true of individuals is true of societies: Some things are forbidden, protected by taboo. Forbidden thoughts are tempting and as the French have long believed, the best way to deal with temptation is to yield to it. It is when Zemmour starts talking of the Muslims in France that his listeners rather wish that he might yield a little less, for beyond his evident sympathy for Vichy, what he has to say betrays a certain willingness to consider as possible undertakings that should remain hidden as prospects. They are forbidden. Immigration? Zemmour is against it and proposes that immigration be reduced to zero. Just who is going to clean his streets, he does not say. The éboueurs in my neighborhood are all of them men of the Maghreb. Zemmour has argued that some eighty to ninety percent of the incarcerated in France are Muslim. He may well be right. He proposes to expel them all if they are not French citizens. Needless to say, it is not a crime in France to have committed a crime in France. Nihil poena sine lege is a principle of Roman and French law.

Zemmour will have none of those legal niceties. Like the coarser figures in the Vichy regime—the odious Louis Darquier de Pellepoix, for example—he wishes chiefly to get on with it and never mind how. The idea that France has been invaded or otherwise infected or that the French are in danger of replacement by Muslims—these are ideas that drag the soul downward. The word expulsion comes too readily to Zemmour’s lips. It would have been far better had he managed to keep down what should never have come up.

Zemmour is what he is: a nimble provocateur with a fine line of gabble. If that is what he is, that is all he is. He is not about to become the president of the French Republic. France is a reasonably well-run, very prosperous, democratic state. It is too late to resurrect the French nation as a factor in French life. That vein is no longer patent, as surgeons say. The French are not about to entrust the administration of their state to Eric Zemmour.

I’d bet my life on it.

David Berlinski is Claire Berlinski’s father. The translations are the editors’.

Often said to be rather like Fox News. Zemmour participated on a show entitled Face à l’Info, its presiding moderator, Christine Kelly, a woman of remarkable composure.

Bompard, a left-wing member of the European Parliament, is Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s campaign manager.

“Jamais un candidat n’a connu en si peu de temps, dans des mesures d’intentions de vote, une évolution telle que celle que connaît Éric Zemmour,” Antoine Gautier, France24. The poll: Baromètre d’intentions de vote pour l’élection présidentielle de 2022–vague 16.

Zemmour, La France n’a pas dit son dernier mot [LF] (Rubempré: 2021), n.5, p. 19. The first edition was published with an embarrassing orthographic error in its initial paragraph: pêcher for pécher, with the result that Zemmour was observed fishing for his sins instead of undertaking them. The edition was quickly removed from the bookshelves. For purposes of this review, the corrected edition is the first edition. The book contains a number of factual errors, as well, some of them outstanding; on p. 25, Zemmour manages to get wrong the dates of the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople by five hundred years; and on p.17, he includes Louis-Ferdinand Céline, quelle crapule, among the great French authors who have “rarement refusé un engagement politique.” If Céline ever had a political thought in his head beyond let’s kill all the Jews, it has been well concealed. And for a great admirer of Napoleon Bonaparte, Zemmour might have taken better care to distinguish him from Napoleon III. C. Demassieux has made available a list of mistakes.

“Nous avons déjà eu Marine Le Pen, elle n’a pas imposé ce débat. Elle a parlé d’autre chose. Quand elle en avait l’occasion, elle a préféré parler de l’Europe, de l’euro, mais pas de cette question. Donc, son tour est passé,” Zemmour, Boulevard Voltaire.

“Nous sommes les deux pôles d’un vrai débat non pas de société mais de civilisation. Ce débat aura lieu, grâce aux sondages. Ça y est. Ce débat ne pourra pas ne pas avoir lieu.” Zemmour, Ibid.

“Le président du tribunal est une femme; le procureur également. La plupart des avocats de mes accusateurs aussi. Sous leur robe noire en guise d'uniforme prestigieux d'une autre époque, elles portent des vêtements de médiocre qualité à l'étoffe fatiguée, sont coiffées à la hâte, maquillées sans soin; tout dans leur silhouette, dans leurs attitudes, leur absence d’élégance, dégage un je-ne-sais-quoi de négligé, de laisser-aller, de manque de goût. On voit au premier coup d'oeil que ces métiers—effet ou cause de la féminisation—ont dégringolé les barreaux de l'échelle sociale. Il flotte une complicité entre elles, proximité de sexe et de classe.” Zemmour, LF, p. 125.

Barthélémy Philippe asks, “Justice, immigration, laïcité, autorité de l’Etat, égalité femmes-hommes… Sur tous ces sujets, les Français connaissent bien la pensée d’Eric Zemmour, qui pourrait bientôt quitter son costume de polémiste pour se consacrer à la campagne présidentielle. Mais quid de ses positions sur l’économie ?” He cites Loïk Le Floch-Prigent: “En revanche, le fil rouge de son positionnement, s’il est candidat, c’est de défendre les intérêts de la France et des Français. Cela passe par la reconquête de la souveraineté et de la fierté économique du pays.” Zemmour has not yet declared his candidacy, but his advisors are much occupied in suggesting that his economic views are of a remarkable grandeur.

Zemmour provides no source for this quotation, which appears on p. 489 of Le Suicide Français (Albin Michel: 2014). (SF). Aside from some mumbo-jumbo about masculine and feminine religions, Islam proving unpleasantly masculine (or the reverse), it would seem Lévi-Strauss had it in for Islam because he did not care for the Taj Mahal. “Grande religion qui se fonde moins sur l’évidence d’une révélation que sur l’impuissance à nouer des liens au-dehors. En face de la bienveillance universelle du bouddhisme, du désir chrétien de dialogue, l’intolérance musulmane adopte une forme inconsciente chez ceux qui s’en rendent coupables ; car s’ils ne cherchent pas toujours, de façon brutale, à amener autrui à partager leur vérité, ils sont pourtant (et c’est plus grave) incapables de supporter l’existence d’autrui comme autrui. Le seul moyen pour eux de se mettre à l’abri du doute et de l’humiliation consiste dans une "néantisation" d’autrui, considéré comme témoin d’une autre foi et d’une autre conduite. La fraternité islamique est la converse d’une exclusive contre les infidèles qui ne peut pas s’avouer, puisque, en se reconnaissant comme telle, elle équivaudrait à les reconnaître eux-mêmes comme existants.” See Tristes Tropiques (Gallimard: 2007), pp. 475-490. Zemmour seems unaware that these remarks, and the chapter in which they are embedded, are widely seen as the weakest sections of Tristes Tropiques and an embarrassment to the author, Raphaël Enthoven asking somewhat plaintively pourquoi ne parle-t-on jamais de l’islamophobie de Claude Lévi-Strauss? The charge of islamophobie is, of course, nonsensical. It suffices to say of Levi-Strauss that with respect to Islam, he did not know what he was talking about. As much is true of Zemmour. See, as well, Abdelwahab Meddeb, “L’islam dans ‘Tristes Tropiques,’” Esprit, no. 377 (8/9) (Editions Esprit: 2011), pp. 77–86.

“J’ai dit dans “Tristes Tropiques” ce que je pensais de l’islam. Bien que dans une langue plus châtiée, ce n’était pas tellement éloigné de ce pour quoi on fait aujourd’hui un procès à Houellebecq. Un tel procès aurait été inconcevable il y a un demi-siècle ; ça ne serait venu à l’esprit de personne,” Lévi-Strauss in La République des Livres.

Zemmour’s conviction that in approving multiculturalism, Paxton is exhibiting a peculiarly American form of naïveté is snooty but absurd. The Russian, the British, the Ottoman, the Austro-Hungarian, and even the Chinese empires were all multicultural.

Islamic terrorism is a concern to the French at every level of society. And rightly so. No one need argue the point.

“Pas un jour sans vol, viol, agression dans la rue ou dans le métro. Pas un jour sans ses innombrables « agressions gratuites ». Pas un jour sans son crime. Pas un jour sans son commissariat attaqué, son école brûlée, ses policiers assaillis, ciblés par des tirs de mortier, ses pompiers caillassés, ses médecins menacés, ses professeurs insultés, ses jeunes Françaises violées, ses adolescents blessés, ses trafiquants de drogue arrêtés et relâchés, ses passagers de RER molestés, détroussés, ses collégiens traités de « sales Français », son vieil homme cambriolé, sa vieille femme brutalisée et assassinée.” Zemmour, LF, pp. 9-10

Shortly before dental surgery, one hopes.

Homicide rates are typically expressed as the ratio of homicides to a population of 100,000. See my essay, “The Best of Times,” in Human Nature (Discovery Institute Press: 2019), pp. 41–69 for details.

The homicide rate in London, 1950, as it happens.

Zemmour, LF, op. cit.

That there is a community of interests between Zemmour’s France and Islam is the theme of Michel Houellebecq’s Soumission.

Cécile Daumas, “Bite Génération.” The headline involves a vulgar pun.

Laval parle: notes et mémoires rédigés à Fresnes, d ’août à octobre 1945 (Paris: 1948), pp. 105-6; Le Procès de Xavier Vallat présenté par ses amis (Paris: 1948), pp. 117-18.

Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, Vol. II (Holmes & Meier: 1985), p. 610, whence the quotation from the English translation of Laval’s Diary, published in 1948. Ibid. p. 637. Hilberg’s discussion of Vichy is one of the weaker sections of his book. Because it was written in the 1950s, Hilberg had limited access to the French archives that would later serve Paxton in his research. In his remarks in SF, Zemmour is quoting from the French version of Hilberg’s work. There seems to be a three-way discrepancy between the 1961 and 1985 English editions and the French edition itself:

“Dans la version de 1961, totalement tributaire sur ce point des archives allemandes, qu’il a d’ailleurs mal lues, Hilberg écrit ainsi que, « dans une grande mesure », la « stratégie » de Vichy, qui aurait consisté à sacrifier les Juifs étrangers pour « sauver » des Juifs français, « fut couronnée de succès. Par l’abandon d’une partie, la part la plus importante fut sauvée. » (Raul Hilberg, The Destruction of the European Jews, Quadrangle Books, 1961, p. 389).

“Or, il s’agit là, précisément, d’une erreur réfutée depuis. Comme on le sait, Vichy n’a pas négocié avec les Allemands le sauvetage des Juifs français en échange des Juifs étrangers, dans la mesure où il avait été convenu entre les deux parties que les Juifs étrangers seraient raflés et déportés avant les Juifs français:

“Dans la version française éditée initialement en 1988 (Fayard, puis Gallimard, 1991 deux volumes), qui résulte de la nouvelle édition de 1985 (éd. Holmes & Meiyer), la phrase sur la « stratégie » de Vichy a, certes, été subtilement modifiée (1988, p. 523): « Dans une certaine mesure, cette stratégie réussit. En renonçant à épargner une fraction, on sauva une grande partie de la totalité. »

“En fait, Hilberg a apporté des modifications ténues lors de la réédition de La Destruction des Juifs d’Europe en 1985, pour tenir compte des travaux de Serge Klarsfeld, Michael Marrus et Robert Paxton. Mais il s’agit surtout, en pratique, d’ajouts de ... notes intrapaginales se bornant à mentionner leur existence. L’ouvrage de Serge Klarsfeld, Vichy-Auschwitz, paru chez Fayard en 1983 pour le premier volume, n’a visiblement été lu par Hilberg, qui ne parle pas le français, que dans sa version allemande.”

In SF, Zemmour appeals to the French edition of Hilberg’s treatise without noticing the change. “Pourtant, le grand spécialiste mondial de l’extermination des Juifs, Raul Hilberg, dont les analyses du processus de la solution finale sont reprises par tous ceux qui écrivent sur le sujet, ne dit pas autre chose dans La Destruction des Juifs d’Europe,” Zemmour, SF, p. 90.

Like Nazi Germany itself, Vichy took pains to put in force anti-Semitic legislation before taking anti-Semitic action. “The most conspicuous of these measures,” Paxton and Marrus remark, “was the Statut des juifs ... It assigned, on the basis of race, an inferior position in French civil law and society to a whole segment of French citizens and to noncitizens and foreigners living on French soil.” Robert Paxton and Michael Marrus, Vichy France and the Jews (Basic Books: 1981). This is to speak in the abstract. The text of the law gives an entirely different impression. Family papers in my possession indicate that Article 3 (a and b) were swiftly violated. On demobilization from the Foreign Legion, where he had fought against the Germans au cours de la campagne 1939-1940, my father was promptly denied the right to work in France. The relevant documents are also on file at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. All that one can say of this wretched legal document is to express astonishment that this great tongue should have fallen so low as to lick the dust.

The experiences of the French under Vichy are corrosive enough to undermine any number of liberal opinions—my own included. The décret Marchandeau was passed by the Third Republic to limit and repress the expression of anti-Semitism, chiefly in French newspapers. Its wording has all of the sinister vagueness of campus free speech codes in the Anglo-American world. It is a direct attack on free speech. The language is, by now familiar enough: “ … when defamation or insult committed against a group of persons, by their origin, race or religion, will have been designed to arouse hatred among citizens or residents ... ” This decree was repealed by the Vichy government. It is painful to observe that the Marchandeau decree worked; its repeal was both a moral and an intellectual catastrophe.

“ … exhortait ses coreligionnaires israélites à rejeter ‘l’obsession du souvenir,’” Zemmour, SF, p. 88. Ses coreligionnaires israélites? Well, well, well.

Lettre pastorale de l'archevêque de Toulouse sur “la personne humaine.” This noble document deserves to be reproduced in full:

“Les mesures antisémites actuelles sont un mépris de la dignité humaine, une violation des droits les plus sacrés de la personne et de la famille.”

What it meant in Drancy in the summer of 1942 is what it meant in plain fact:

“The children were in bare rooms in groups of one hundred. Buckets for toilet purposes were placed on the landings, because many of them could not walk down the long and inconvenient stairways to the toilets. The little ones, unable to go alone, would wait agonizingly for help from female volunteers or another child. This was the time of the cabbage soup at Drancy. This soup wasn’t bad, but it was hardly suited for children’s digestion. Very quickly all the children suffered from acute diarrhea. They soiled their clothing, they soiled the mattresses on which they spent night and day. With no soap, dirty underclothing was rinsed in cold water, and the child, almost naked, waited for his underclothes to dry. A few hours later, a new accident, and the whole process had to be repeated.

“The very young often didn’t know their names, and then one asked their friends who sometimes gave some information. Family and first names then being established, these were inscribed on little wooden dog tags …

“Every night one heard the perpetual crying of desperate children from the other side of the camp, and from time to time the distraught calling out and the wailing of children who had lost all control.”

I was not there by the grace of God. The author is Georges Weller, whose descriptions provided evidence at the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Cited in Paxton and Marrus, p. 264.

“Defining a legitimate government as ‘one whose authority, accepted by the people it governs, provides for the basic requirements of the public welfare’ it concludes after a lengthy proof ‘[that] a government is not created to hand over its people but to defend them. It should act for its people and not against them … ’” Marc-Olivier Baruch, “Vichy and the Rule of Law,” Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem, 6 | 2000, 141-1. The reference is to Gaston Fessard, Au Temps du prince esclave: Ecrits Clandestins 1940-1945 (Critérion : 1989), pp. 87-88.

Charles Maurras.

Xavier Vallat, Le nez de Cléopâtre (Souvenirs d’un homme de droite, 1918-1945) (Paris : 1957), p. 226. So French, as Zemmour might remark—as he does remark in his appreciation of Georges Bernanos, who in a fatally clumsy attempt at irony remarked that Hitler a déshonoré l’antisémitisme. Bernanos wrote on the eve of war. He had no idea what was coming. Zemmour knew what had come. His idea that this is a “a very French” form of irony manages to insult every party concerned.

Paxton and Marrus, op. cit., p. 99.

In 1940, both my parents had lived in France for years; both spoke perfect French, and both were graduates of the École Normale de Musique. Already a distinguished German concert pianist, my father was a student of Alfred Cortot in piano and Nadia Boulanger in composition. He served in the French Foreign Legion and was decorated lavishly for services in combat. Assimilated enough? Apparently not. Cortot refused all requests for assistance. He was at the beginning of his career as a Nazi collaborator—a career, it is satisfying to recount, that destroyed his reputation. My parents were denied the right to work in France and at the last possible minute managed to escape France for Spain. No, not assimilated enough at all.

In The Alien Corn, Somerset Maugham captures this perfectly when he has a defiant and successful British Jew refer to his own “oriental barbarism” on the grounds that it is better to acknowledge what cannot be expunged.

Thomas Mann made the same mistake in remarking that German culture could be found wherever he happened to be standing. He happened to be standing in southern California; German culture remained where it was—in Nazi Germany.

Edmund de Waal’s The Hare with the Amber Eyes is exquisite on this point, and so is Gregor von Rezzori’s Memoirs of an Anti-Semite. Zemmour should have read these books; it is shame that he did not.

Franz Kafka’s Der Bau expresses this particular system of anxieties perfectly.

I discuss this further in “A Passage from India.”