What Ukrainians (and the world) should learn from the Manafort pardon

Don’t rely on Americans to prosecute your criminals. Do it yourself.

From the editors:

We realize that readers around the world are right now—and above all—preoccupied with the United States’ instability.

We published Part I of last week’s two-part essay, treating the massive new investment deal between China and the EU, on January 6. We had spent the day laboring on the essay, so focused were we on our work that we didn’t look at the day’s news.

After pressing “send,” we checked Twitter.

When we grasped what had happened, we understood immediately that no one would read what we’d written. There is only so much attention in the world.

We thought it a shame. The essay put the dysfunction of the United States in its global context, and in that light, unfortunately, the insurrection in the capitol is even more sinister, if such a thing were possible. You can read it now, if you missed it:

No one can ignore China, Part I

No one can ignore China, Part II

Recently, we asked cosmopolitan globalist Vladislav Davidzon to explain the Ukrainian perspective on Paul Manafort’s pardon. He delivered exactly what we asked—under extremely difficult personal circumstances—but we wondered if it was fair to him to publish his essay today. Would anyone read it? We asked ourselves if perhaps we should postpone his article, disrupt our schedule, and write about the obvious: America’s Kristallnacht.

No, we decided. That is not what we do. We said so at the outset: “We will not chase breaking news. It breaks, we shrug.” We founded the Cosmopolitan Globalist because the Anglophone world is oversaturated with news about itself and devoid of news about anyone else. If you want the perspective of Washington insiders about Trump, dozens of newsletters will offer you that perspective, better than we can; you’re spoiled for choice. If you’d like a bigger perspective, keep reading.

You don’t need another breathless report about Donald Trump’s latest antics—not even if a mob of his crazed followers siege the United States capitol to prevent American legislators from carrying out a peaceful transfer of power, besmirch it with Confederate flags and Nazi symbols, bludgeon a police officer to death with a fire extinguisher, ransack the building, and literally defecate in it. That this really happened is, we grant, distracting. But we proceed—steady, if perturbed—In our mission.

In a concession to the reality that no one can really focus on anything else, we will also publish a special issue, tomorrow, treating the global reaction to the coup attempt. It will contain advice from people who live in countries where this sort of thing happens more frequently. They know practical things Americans should now consider, especially if the next attempt is successful.

Tomorrow’s special edition will be for subscribers only.

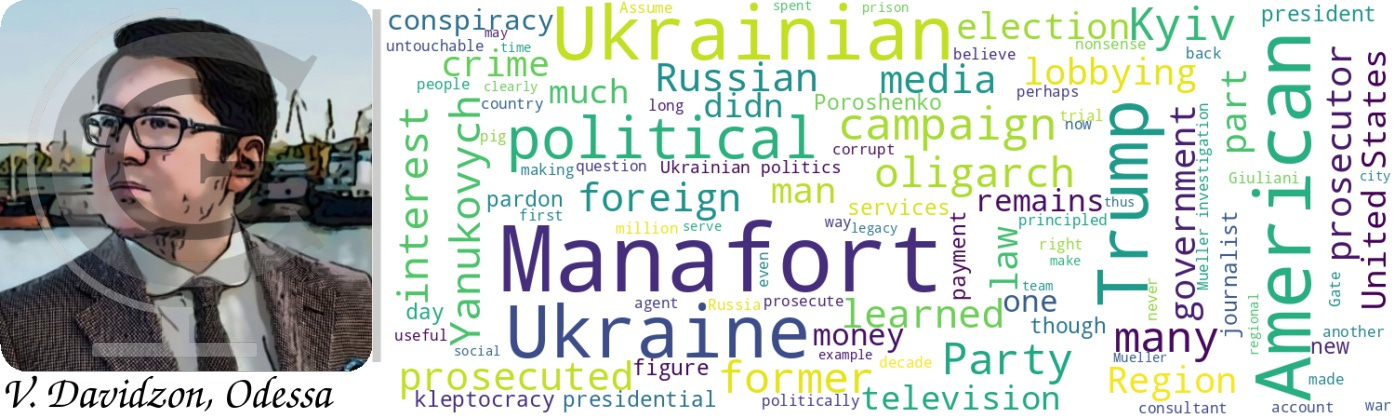

By Vladislav Davidzon, Odessa

What Mueller taught Ukraine

Empowered to investigate Russian interference in the United States’ 2016 election, Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s team undertook a thorough discovery process. The team uncovered, and made public, a trove of information about Donald Trump’s former campaign manager, Paul Manafort, and his machinations in Ukraine. Fascinated Ukrainians gained insight into the way the Ukrainian political elite deals with the Americans. More importantly, we learned that irrespective of Manafort’s guilt under United States law, he had clearly broken Ukrainian laws.

Ukrainians are dejected that Manafort has been sprung. But we have no right to be. We relied on Americans to prosecute him instead of doing it ourselves. Watching Manafort leave prison and return, triumphant, to his lobbying efforts may disconcert many in Kyiv, but we should draw a lesson from this prolonged farce. If you want the law enforced in your country, prosecute your own criminals. That is what sovereignty is about.

What Americans learned about Ukrainians

Ukrainian politics, as Americans were forced to learn, are boisterous and lively. Ukraine’s elections are ferociously competitive. The country’s surreal, wild, and often sociopathic politics devolve, in part, from regional social cleavages. Different parts of the country are radically different. Western commentators focus on Ukraine’s linguistic divisions, but they’re not a genuine problem. The genuine problem is this: From the Holodomor to the ongoing war in the east, Ukraine is a traumatized country, and the cursed process of coming to terms with the Soviet legacy has been geographically, socially, and psychologically uneven.

Different regions of Ukraine have achieved radically different levels of economic development and thus have radically different visions of the future. Ukraine’s infrastructure remains primitive. It has taken me 18 hours to get from one city to another. Most people have never spent time outside their region. Older people, pensioners, often lack the money to go to cafés, or travel; they spend their time at home watching propaganda television. Ukrainian politicians routinely ratchet up these social tensions to serve their own ends. Meanwhile, Westerners looking to make quick buck are attracted to the mountains of cash stockpiled in the Ukrainian black and grey economies.

What Ukrainians learned about Americans

Western political consultants have long been deeply involved in Ukrainian politics. In the 2010 election, for example, Manafort and his crew—many of them alumni of the International Republican Institute—helped Viktor Yanukovych win the Presidency. The skills foreign consultants bring, such as their mastery of modern polling and campaigning techniques, can swing an election.

The documents unveiled during Trump’s impeachment trial featured blow-by-blow accounts of the way Ukrainians lobby D.C. These fascinated us: The American investigation revealed more about Ukrainian politics than Ukrainian investigative journalism ever could.

We also learned that American journalists are vacuous, partisan, and credulous. Text dumps in the US media showed us that the Giuliani conspiracy was an intricate and very silly feedback loop. Ambitious schmucks like Andriy Telizhenko (a former low-ranking diplomat and political operative), General Yuriy Lutsenko (a lame-duck prosecutor), and Andrei Derkach (a now-sanctioned Russian agent and Ukrainian MP) produced nuggets of partly-true but torqued-up information, or just made up something deranged—or maybe not—and fed it to the gullible American media. Two days ago, the US Treasury sanctioned most of these figures for attempting to influence the 2020 US presidential election.

Some of these people were working with Russian intelligence, which we know because the US Treasury said so—and sanctioned them. They provided much of the nonsense; mercenary personalities in Kyiv packaged their own kompromat with tantalizing tidbits for American consumption. Some of it was nonsense and some of it was real and it was hard to tell which was which. Giuliani read these revelations and instructed his minions in Ukraine to search for more evidence of this seemingly plausible (or insane) thing.

The minions found a host of opportunists: Some were malicious Russian operatives, assets, or fellow-travelers; but many in Kyiv were only too happy to make up anything their American visitors wanted to hear—be they Democratic Americans or GOP Americans—because now they were being paid to spout nonsense, not only in dollars (though that too, of course) but in important-sounding meetings, connections, television coverage, and fame, all emanating from Washington, D.C.—the whole game calling to mind nothing so much as Auden’s lines:

God bless the lot of them, although

I don’t remember which was which:

God bless the U.S.A., so large,

So friendly, and so rich.

Any new material they found was then repackaged by partisan American journalists who so clearly knew nothing about Ukrainian politics that they retailed it without asking any questions.

Giuliani instructed the hapless Ukrainian government, essentially held hostage by these repackaged stories, to find more like them. Or to hold meetings it had no interest in holding with odd and disreputable characters. This gave semi-sidelined and discredited schmucks like Lutsenko an incentive to unearth more self-serving nonsense, which was then fed directly back to Giuliani. The former prosecutor—who back in his glory days took down the New York City mafia—was now doddering and credulous; he eagerly believed everything these notorious scoundrels fed him; and they used him to serve their own personal and political ends.

The other side of the American partisan divide was no more shrewd. CNN, for example, gave extensive airtime to Serhiy Leshchenko, presenting him as a neutral observer who could explain the complexities of Ukrainian politics to mystified Americans. They failed to notice that the former MP and investigative journalist was up to his neck in complex court intrigues; they presented him as someone perfectly qualified to explain this story to befuddled Americans who, understandably, couldn’t quite follow all the intersecting plot lines.

Thanks to the Mueller investigation and Trump’s first impeachment, Ukrainians learned how all of this works. Many were startled to discover that much like the Wizard of Oz, the mighty United States was just an old man with a megaphone and a smoke machine, frantically pulling at levers.

Why wasn’t Manafort prosecuted in Ukraine?

We learned so much more, though. We learned that Manafort had kept tens of millions of dollars in 31 bank accounts spread across more than a half a dozen countries. We learned that the former presidential administration kept Manafort’s services off the books, making payments through intermediary companies owned by Ukrainian oligarchs and regional officials, including Rinat Akhmetov, Borys Kolesnikov, Serhiy Lyovochkin, and Dmytro Firtash.

Ordinary Ukrainians always had their suspicions, of course. But we wouldn’t have known precisely how it worked if Manafort’s right-hand man, Rick Gates, hadn’t laid it out, in detail, at Manafort’s trial. Gates explained the web of some fifteen connected Cypriot shell companies and another dozen offshore entities: Ukrainian oligarchs paid Manafort and Gates millions for their services; the money then got wired back and forth among these entities—many of them controlled by Ukrainian oligarchs—to disguise these illicit payments as internal loans and conceal the income from American authorities.

And what were those services? Manafort advised Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych and his Russophone, Donbass-based political party, the Party of the Regions. Nota bene: the Party was politically and culturally aligned with Moscow, but not quite the slavish proxy of Russian geopolitical interests that numerous American accounts have suggested. The party never had much interest in seeing Ukraine’s national interests totally subsumed or assimilated by Moscow; it represented the interests of the region and its political clans above all else.

Manafort spent nearly a decade in Ukraine as a consultant to the Party of the Regions and to Yanukovych personally, crafting policy and inculcating in party members proper manners and dress habits. He was part of a generation of consultants who taught Ukrainians how to hold elections and win them. The tools he brought with him, such as precise and modern polling, gave the Party of the Regions winning campaign themes. Later, he pivoted; he planned to help Ukraine integrate—eventually—into the European Union under his “Engage Ukraine” plan. He brought in heavyweight European politicians such as former Polish president Aleksander Kwaśniewski—lobbying guns for hire.

Most of this falls under the penumbra of “What lobbyists do.” Lobbying isn’t illegal in Ukraine. What is illegal, under Ukrainian law, is breaking the laws governing the behavior of political parties—and the entire illicit financing scheme.

So why wasn’t he prosecuted for these crimes in Ukraine? Because Ukraine, for the most part, still lacks an independent judiciary. So long as Manafort’s client was Ukraine’s president, Manafort was too big to fail.

The Black Ledger

After Yanukovych absconded to Russia, his extravagant Mezhyhirya Residence was thrown open to the public. Ukrainians marveled at the private zoo, the peacocks and ostriches, the personal golf course and vintage car collection, the kitschy handmade galleon floating on a private, man-made lake.

Manafort offered his services to the administration of the new president, Petro Poroshenko, but he didn’t get the account. The regional oligarchs who used to pay his invoices—an informal tax or tithe levied on them by Kyiv—ceased making payments. Manafort was in debt to Kremlin-proxy and oligarch Oleg Deripaska (a proposed joint investment in real estate went awry), and he was accustomed to a profligate lifestyle. He needed a new source of income.

Famously, though, he refused payment for running the Trump Presidential campaign. His subordinates and colleagues told me that his goal was to use Trump’s victory to create the ultimate D.C. lobbying shop: He meant to become the biggest lobbyist in town.

In the summer of 2016, Poroshenko’s domestic opponents miscalculated terribly. Believing Hillary Clinton would win, and hoping to guarantee this, they provided the so-called Black Ledger to the media and the DNC. The Black Ledger, discovered in the charred remains of the headquarters of the Party of the Regions—which had been burnt down in the final days of the Maidan revolution—contained handwritten records indicating, among other things, that the Party had illegally funneled US$ 12.7 million to Manafort, in cash. These records were conspicuously displayed at a Kyiv news conference and simultaneously published by British and American newspapers, forcing Manafort to resign from Trump’s campaign.

Trump, it seems, blamed all of Ukraine for the imbroglio. Kurt Volker, the former special envoy to Ukraine, testified under oath during the first impeachment trial that in White House meetings, Trump had ranted, “Ukraine is a terrible place, they’re all corrupt, they’re terrible people, they tried to take me down.” Trump’s paranoid response to the Russia investigation, combined with what he viewed as an illicit Ukrainian effort to sway the 2016 Presidential elections, led him to blackmail Kyiv and thus to Ukraine-gate.

This is not a war against kleptocracy

But Ukrainians should not be interested in this widely misunderstood story, nor in the bizarre, cinematic drama that ensued. What should interest Ukraine is that it took an American prosecutor to expose Manafort’s crimes and put him behind bars. Furthermore, the prosecution that put him behind bars devolved from an American political scandal, not from the United States’ principled and consistent stance against kleptocracy—and certainly not from a campaign against kleptocracy in Ukraine.

It remains unclear whether Manafort knew anything that could incriminate Trump. A jury in Northern Virginia convicted Manafort of eight counts of financial fraud and deadlocked on ten other charges. Facing another trial, on related charges, in the District of Columbia, Manafort accepted a bargain: He would plead guilty to several felony counts, including financial fraud and conspiracy to obstruct justice, in exchange for answering “fully, truthfully, completely and forthrightly” questions about “any and all matters” of interest to the government.

In November 2018, however, federal prosecutors announced that Manafort had lied to them, violating the terms of the deal and thus rendering it void. They announced their intention to try him—and nail him—on all of the charges. Manafort, who habitually thought that he was smarter than everyone else, entered a guilty plea; and Trump, meanwhile, showed his hand:

The lead prosecutor in the Mueller investigation says the investigation team simply assumed that Trump had—by means of this Tweet and perhaps otherwise—offered Manafort a pardon in exchange for his silence. Perhaps. Or perhaps there was no grand conspiracy with Moscow in the first place—or if there was, Manafort didn’t know about it.

Everyone has noticed, and derided, Trump’s odd and obsequious behavior around Vladimir Putin. Many of Trump’s enemies are absolutely persuaded that he’s the Kremlin’s Manchurian candidate. Figures in the legacy media who should have known better have given themselves over to elaborate conspiracy theories to this effect. Yet despite the frenzied searching, no one has come up with the smoking gun or the kompromat.

I would posit that Manafort didn’t have it, either. Maybe Manafort didn’t provide the testimony Mueller wanted because he was counting on a pardon from Trump. But Occam’s Razor says he couldn’t provide the testimony. Rachel Maddow’s theory—that Trump is an out-and-out controlled secret asset of the Russian intelligence services, Putin’s marionette—was always far-fetched, and she squandered the institutional credibility of the legacy media in suggesting so. While Putin no doubt rejoices in every bit of destruction Trump has unleashed, Trump doesn’t have the discipline to be a professional Russian asset. He couldn’t organize a piss-up in a brewery. His narcissism and bad memory militate against the hypothesis that he’s capable of being involved in the kind of complex conspiracy that many American journalists posited. It is much more plausible that Trump is what Russians would call a useful idiot.

Assume that Trump has no moral compass. Assume he still has no idea why his behavior toward Russia alarmed the American establishment. Assume he sincerely believes the Mueller investigation was, as he continues to insist, a witch-hunt—a personal attempt to destroy him. Assume Trump genuinely believes a cabal of deep-state spies and bureaucrats is out to get him. All of this seems plausible. If so, we should conclude that Trump pardoned Manafort because he sincerely believes Manafort was politically persecuted. In this case, Trump may be half-right: Disagreeable though he may be, Manafort was politically prosecuted, if not politically persecuted.

Was Manafort’s pardon a grave injustice, as many in the US media have passionately declared? Yes and no. If American journalists believe Manafort was prosecuted as part of a principled fight against kleptocracy, they’re kidding themselves. Manafort has already spent two years in prison. The pardon means he won’t serve the next seven years of his sentence, which was increased when he formally ceased cooperating with the Mueller investigation. He lost millions of dollars in the civil forfeiture; Trump’s pardon won’t bring any of that back.

Manafort is not a sympathetic character. Leave out of the moral equation the inherently louche nature of his work: He was undeniably guilty of tax evasion, money laundering, and failing to register as a foreign agent.

But in truth, there never was a principled fight against corruption and violations of the Foreign Agents Registration Act in Washington. You’d know if there had been: They’d put half the city away in a single day. Manafort helped create the Swamp; Trump made it even Swampier.

Manafort was prosecuted because he was close to Trump. He was an idiot to expose himself that way, given the cemetery’s worth of skeletons in his closet. He was foolish and he was hubristic. Taking the reins of the Trump campaign was obviously going to end badly.

Manafort behaved as if he was untouchable. Why did he think so? Americans and Ukrainians alike would profit from asking that question.

The Untouchable

Manafort figured he was untouchable because he’d grown accustomed to the sensation—after all, he’d enjoyed decades of tacit protection; or at least, sustained indifference, from one after another American government. He was untouchable in Ukraine because he was a valued legate to the Ukrainian political establishment—and that establishment has, for decades, protected its own. No major political figure ever goes to prison in Ukraine for crimes committed at the top of the Ukrainian power vertical.

When Poroshenko first came to power, in 2014, he de facto ratified this understanding by making a series of deals with his peers in the political elite that crossed every political and economic red line. No senior figure but Yanukovych, who by then was safely in Russia, was ever prosecuted. To be fair to Poroshenko, this allowed him to govern, rather than spend precious political capital fighting ultra-powerful oligarchs who possess both parliamentary proxies and vast media holdings.

Ukraine’s current president, the former television actor and comedian Volodymyr Zelensky, ran a populist campaign against corruption. He attacked Poroshenko`s compact on the campaign trail. But once in office, he likewise failed to prosecute a single senior member of the oligarch class. Perhaps Zelensky, like his predecessor, concluded that taking down an oligarch, or a major political figure who owns a television network, would just get in the way of governing and implementing his agenda for reform. Zelensky, unlike his predecessors, owns no television networks. He is reliant on good relations with the oligarchs to convey his political message.

Whatever Ukraine’s leaders are thinking, the fact is that only Americans have succeeded in putting senior Ukrainian miscreants behind bars. This was true of the massively corrupt former prime minister, Pavlo Lazarenko, too: He was prosecuted and jailed in California for money-laundering, corruption, and fraud. If Manafort saw justice—however briefly—in a Virginia courtroom, it was not because Ukrainians themselves had the balls to take him on.

Manafort operated at the highest levels of government in Kyiv. He committed serious crimes in multiple jurisdictions. It is a criminal offense, in Ukraine, for a political party to make off-the-books payments. Manafort was both the accessory and the beneficiary of that crime. Yanukovych illicitly transferred state funds to Manafort by means of a system everyone concerned knew damned well was illegal under Ukrainian law. Manafort was both an accessory and beneficiary of that crime, too.

Yet he would never have been prosecuted by Ukrainians or tried in a Ukrainian court. Even if the prosecutors had the will, they wouldn’t have dreamt of taking on someone with that kind of political protection. Only American prosecutors and judges could bring him to justice. When they did, there was an outbreak of joy among reformers in Kyiv, who celebrated in cafes, on television talk shows, and in their social media posts.

Their vicarious pleasure was misplaced. Americans nabbed Manafort for violating American laws, not Ukrainian ones. Why should Ukrainians care about that? Our system remains corrupt and incapable of prosecuting all the other Manaforts.

The American system remains corrupt, too. Foreign lobbyists continue to defy the Foreign Agents Registration Act. There are no common ethical or legal norms governing foreign lobbying in the United States. Any hope that Trump might drain the swamp—even if inadvertently, or through the power of his counter-example—has long since evaporated.

He was our boy

After many long conversations and interviews with Manafort’s associates and subordinates in Kyiv, I have concluded that he was a world-class sociopath. I’ve also concluded he enjoyed the tacit protection of sectors of the American government for decades. He was a campaign adviser to Ford, Reagan, Bush, and Dole. In the 1980 presidential campaign, he worked under the man who was to become Reagan’s CIA Chief. He then founded a lobbying firm and represented clients significantly more distasteful and violent than Yanukovych. He didn’t scruple against lobbying for Mobutu Sese Seko or Jonas Savimbi. It’s reasonable to think many in the US government viewed him as a useful tool of Cold War US foreign policy—or at least, “basically on our side.”

Several former American ambassadors to Kyiv confirmed to me, in detail, that Manafort had been very useful to the State Department: He had advanced the US agenda and passed the right signals and messages on to the brutish Yanukovych. He was always a useful backchannel.

Manafort’s defenders have claimed that he pushed Yanukovych toward engaging and eventually integrating with Europe. Manafort discovered though his polling (no one had really done it in Ukraine before) that a majority of voters wanted to be part of the EU—even if a solid majority, at the time, did not want to be in NATO. This was the strategy that created the bidding war for Kyiv’s loyalty.

Manafort went afoul of American interests in his money-making schemes with Oleg Deripaska. Because of this, and because he undertook assignments in the Balkans to lobby against NATO and American foreign policy interests, Americans grew sick of him. But he only became radioactive after joining the Trump campaign. And he didn’t become radioactive because of his crimes overseas, which were hardly a shock to the US government.

The US clearly did not undertake to prosecute Manafort because we’d had it with the rot in Ukraine. Or the United States. Manafort’s prosecution was political, not part of an independent judiciary’s principled assault on kleptocracy. The latter has not yet happened—not in Ukraine, and not in America; both political cultures are more similar by the day.

… Twelve voices were shouting in anger, and they were all alike. No question, now, what had happened to the faces of the pigs. The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.

Vladislav Davidzon is a journalist who divides his time between Ukraine and France. He was the founding editor of The Odessa Review and is Tablet’s European Culture Correspondent. He is a non-resident fellow of the Atlantic Council.

Claire and co, I am so happy that you all are doing what you are doing and providing some insight into the machinations happening in other parts of the world, the other political systems and conflicts that we never hear about over the din of American politics. While those are certainly interesting, it is nothing compared to what I am learning about the world because of the efforts that you all are making. Happy to be supporting you all. Hoping to one day know enough to offer some thoughts of my own.

Very informative and well worth reading. I couldn’t help but notice the parallels between Ukraine and the United States, especially this comment by Mr. Davidzon;

“Zelensky, unlike his predecessors, owns no television networks. He is reliant on good relations with the oligarchs to convey his political message.”

Couldn’t we say exactly the same thing about Biden (and for that matter, Trump)? They own no media outlets. Aren’t they dependent on oligarchs like Jeff Bezos, Jack Dorsey, Mark Zuckerberg, Sundar Pichai, Robert Iger, Rupert Murdoch, Brian Roberts and Shari Redstone to get the word out?

Are American oligarchs really any less powerful or corrupt than Ukranian oligarchs?

Could that be the reason a large percentage of Americans detest the status quo (which Biden represents) in the same way Ukranians do? Speaking of President-Elect Biden, perhaps Mr. Davidzon will tell us what to make of Hunter’s escapades in Ukraine.

Mr. Davidzon describes the Ukraine as a bifurcated society: one half oriented towards the West and one looking longingly to the East. Is Ukraine really any more bifurcated than the United States where the cleavage is between those who are college educated and those who aren’t?

Is our country any less embittered than Ukraine? Don’t both nations suffer from the same ailment; oligarchs who care only for themselves.