The Future of Sino-African Relations

Ken Opalo sorts facts from hysteria—and offers China some advice.

Claire—Our readers were just about evenly divided between clamoring for more Ken Opalo (I agree—he’s terrific) and wanting a fresh edition of Global Eyes. So today we’ll do both. Global Eyes will be in your In Box this evening. Meanwhile, if China’s relationship to Africa interests you, make a point of following the links in this interesting essay. They lead to books and articles that are well worth adding to your reading list.

China and Africa in a multipolar world

By Ken Opalo

I. Enabling friends’ bad habits

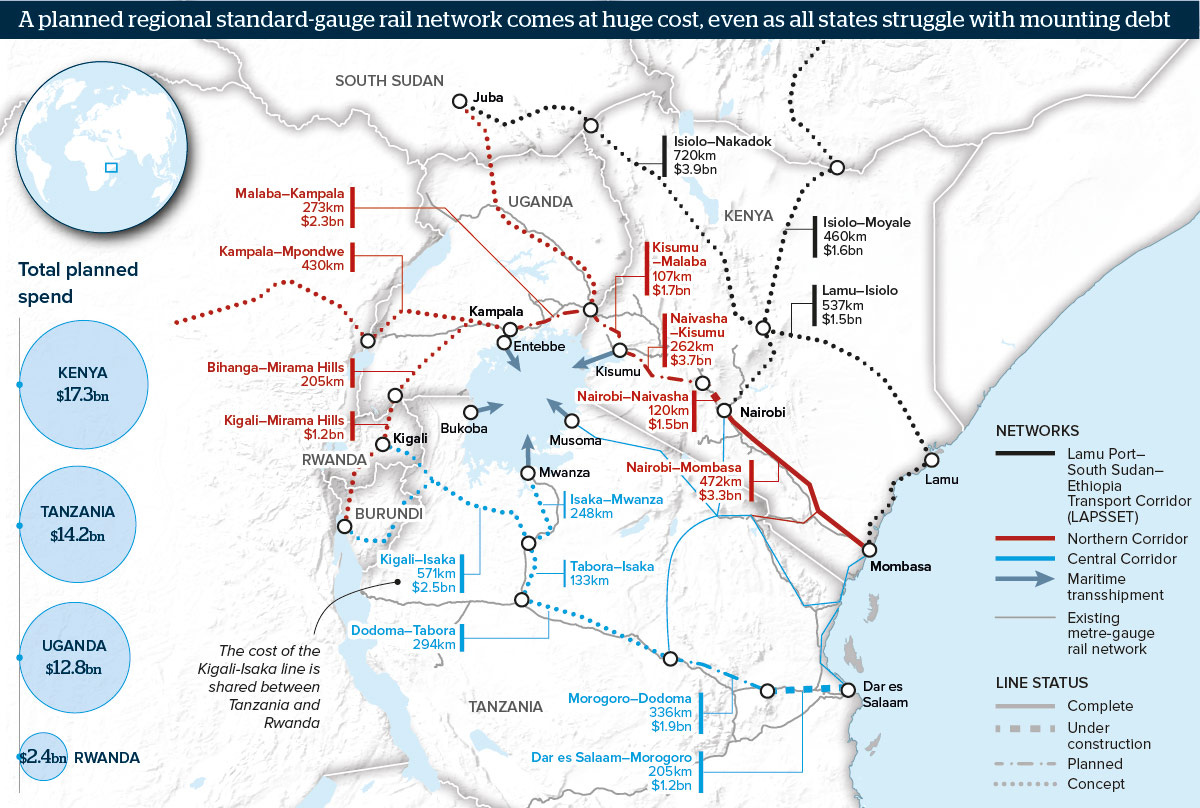

As The Economist once put it, some countries get a loan to build a railway, but Kenya might have built a railway to get a loan. Kenya’s new 700-kilometer standard gauge railway cost US$4.7 billion to build. It was also wildly overpriced and poorly thought out. Kenyan analysts’ informed protestations were roundly ignored. It later turned out that the line would only be commercially viable if extended through Uganda to Rwanda (see the map below). Despite the Kenyan government’s coaxing of haulers away from the roads, the rail traffic is not enough to service the loan.1

Both Uganda and Rwanda have yet to fully commit to the idea. Tanzania’s planned line to eastern DRC will likely sap more traffic from the Kenyan line. In any case, Kenya needs another loan to extend the line to the Ugandan border, even as it drains its Treasury to service the original loan. At the moment, the railway ends abruptly in the middle of nowhere (so to speak).

In short, the Kenyan standard gauge railway is currently quite the white elephant. It is also Chinese designed, financed, and built.

Angola presents a related—albeit somewhat different—fiscal boondoggle. After emerging from decades of conflict, Angola found in China a partner of convenience with whom it could barter its oil for infrastructure and other imports. On paper, this seemed like a good idea, especially by contrast with the standard “Western model” of tax havens and oil-for-elite-properties in Europe and the US. By 2020, more than 60 percent of Angolan oil exports flowed to China. Angola also quickly became the largest recipient of Chinese loans in Africa. During the same period, Angolan elites drove their economy into the ground—including by bleeding the national oil company, Sonangol, dry.

At the center of Sino-Angolan commercial relations was the “Queensway Group” of Hong Kong, a web of companies with reported links to Chinese intelligence and state-owned companies. A significant share of the pillaging of Angolan public wealth was reportedly channeled through the group. Given the alleged links to Beijing, Chinese officialdom must have known what was going on.

Forget the misplaced hysteria about China’s so-called debt-trap diplomacy in Africa, common in much of the Western press. (Commercial loans from Western lenders or Western-led multilaterals typically dominate African loan books.) The biggest strategic challenge for African countries arising from China’s recent commercial forays in the region is the apparent insouciance about rank bureaucratic incompetence, crippling corruption (not the “facilitation” kind), poor project implementation, and the proliferation of failed mega-projects.

Such failures are not just bad press for China. They actively undermine Beijing’s geopolitical ambitions, in addition to jeopardizing African countries’ hard-won macroeconomic stability. Presumably, China wants African allies that are more than just votes at the UN—it wants friends whose economic capabilities and political influence amplify China’s power on the global stage and showcase the superiority of the “Chinese model” of economic and political management, or simply demonstrate that it pays to be an ally of Beijing, regardless of ideological orientation. Actively enabling the colossal misbehavior of ruling elites who lack an encompassing interest or long-term vision for their countries (as in Kenya and Angola) is as far from this ideal as one can get.

For a country (and regime) that prides itself on its long-termism, China’s Africa policy serves up a lot of questionable short-term thinking.

II. The future of Sino-African relations

There is no doubt that as a revisionist global power, China wants to be a favored partner of African states. At multiple Forum on China–Africa Cooperation meetings since 2000, Beijing has committed billions of dollars in loans (and some grants) to African economic development, totaling about U$160 billion since 2000. The mostly positive effects of this are readily visible across the region. For 33 years straight, the Chinese foreign minister’s first international trip has taken him to Africa, an important symbolic performance of the region’s strategic importance to Beijing. China also likes to engage in high-visibility direct diplomacy, such as constructing the African Union’s new headquarters, state houses (“palace diplomacy”), parliaments, and other civic and cultural buildings.

However, if China wants to build even stronger relations with African countries and maintain the significant goodwill it enjoys across the region (see image above), it has to learn from the mistakes of the last twenty years. Over the past two decades, Chinese-financed and Chinese-built roads, power lines, dams, and other infrastructure have unambiguously improved livelihoods in Africa (despite all the corruption and questions about quality). Yet all that investment can easily be swept down the drain by the consequences of African and Chinese officials’ short-termism.

I do not think that China is doomed to failure in Africa. But it can fail if it does not take a more constructive approach to commercial relations with African states. Deliberate efforts to ensure incentive-compatible deals that nonetheless generate sustainable growth—and don’t saddle countries with white elephants— will be particularly apposite as Chinese growth slows, interests rates rise, and cash becomes scarce. There is corruption, and then there is corruption.2

At this critical juncture in African history, Beijing has a unique opportunity to build its global reputation through constructive partnerships. As a corollary, failure will tarnish its global brand. Consider that regardless of their debt profiles, popular narratives about debt overhangs in African states invariably focus on Chinese loans. Over time, African publics may come to associate China with economic mismanagement, thereby limiting the scope of Sino-Africa relations.

Under the assumption that China will remain a valuable economic partner to African states into the foreseeable future, below I suggest how Beijing may avoid the pitfalls of short-termism.3

Externalize Chinese bureaucratic competence:

A lot of people like to credit autocracy with China’s economic miracle. They are wrong (see here, here, here, here, and here). It takes a lot more than crude coercive power to lift hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. Democracies and autocracies alike excel when managed by competent governments sitting atop professional, goal-oriented bureaucracies (which need not be perfect, or corruption-free). One of the most valuable lessons China could offer its partners abroad, regardless of their regime type, is how to cultivate and sustain bureaucratic competence at scale.

Mostly under-governed and misgoverned, African states would particularly benefit from assistance in boosting their bureaucratic capacity. In this regard, China has unique advantages. Inured by centuries of strong statehood, most Westerners think of governance reforms only in terms of constraining government—even in contexts where governments barely exist! China would provide a different approach that professionalizes and extends the reach of African governments.

Rather than wasting time and resources on party-to-party exchanges (China should consult Western attempts to export their political models to Africa), Beijing should instead develop an ambitious goal of helping its African partners build competent, development-oriented bureaucracies. The idea here is that Chinese assistance would yield bureaucracies that are good enough (warts and all) to jumpstart African states’ economic takeoff, much as happened in China. Ideally, such bureaucracies would be compatible with politicians’ incentives but would not, for example, approve the construction of commercially unviable railways to nowhere just so politicians can get their cut.

Invest in African agriculture:

African states have some of the least productive agricultural sectors in the world—mostly due to a lack of state investment in infrastructure, inputs, and extension services (see figure below). Low agricultural productivity, in turn, is an important stumbling block to industrialization in the region (not to mention the human cost of famines and threats to political stability).

Investing in African agriculture would be a win-win proposition for China. First, it would provide its African partners with a strong basis for economic development and political stability. Second, it would contribute to China’s strategic foreign investments in agriculture to supply its domestic market—especially its growing middle-class demand for meat and dairy. Third, it would help reduce the yawning trade deficit with African countries, reducing associated tensions.

Depending on the country, Chinese investments would focus on research and development, irrigation, mechanization, and other inputs (like fertilizer), farm-to-market logistics (especially safe storage), and agro-processing.

Be more aggressive in adding African links to Chinese value chains:

Mass job creation is the best way to quickly lift millions of people out of poverty. No contemporary country knows how to do this better than China. As the world’s factory, China is a key part of global value chains. It is also working on moving up the value chain to higher-value products, and facing a demographic wall that will raise the cost of Chinese labor. A number of Chinese firms have begun production in African countries precisely for these reasons.4

Yet Beijing could do more to boost African participation in global value chains. For example, it could provide policy incentives for collaborative ventures that result in technology transfers and boost managerial know-how. It could also eagerly embrace African attempts to add value to mineral exports. And as with improvements in agriculture, African participation in Chinese value chains would help to reduce African states’ trade deficits with China.

Expand investments in African human capital:

By 2015, China had already surpassed both the US and the UK as the leading destination of Africans studying overseas (before Covid, estimates put the figure at more than 74,000 African students). This was not by accident. Investing in its partners’ human capital is a core part of Chinese foreign policy. These investments coincided with the explosion of demand for higher education in African countries. Following the long decade of economic stagnation (1980-1994) and disinvestment in public services (including education), African countries aggressively expanded access to education, including tertiary education. However, decades of disinvestment mean that the available capacity in public and private universities cannot meet the sky-high demand. This demand can be met by foreign universities, including China’s.

Training scientists, engineers, journalists, or businesspeople at reputable Chinese universities will go a long way toward increasing the stock of quality human capital in African countries. It would also provide a base for strengthening links between African and Chinese firms, in addition to providing potential employees for Chinese firms operating in the region. More broadly, it would be a valuable investment in Chinese soft power for the long haul.

Cultivate a more sophisticated understanding of African politics:

Formally, China espouses a policy of non-interference in its African partners’ domestic affairs. In practice, China seeks to build personal relationships with political and economic elites in the region. There have also been sporadic attempts to establish formal ties between African ruling parties and the Chinese Communist Party. Often, these efforts betray a misunderstanding of African politics motivated by a projection of the Chinese system.

To be blunt, Beijing doesn’t seem to understand how to deal with roving bandits with short time horizons (due to elections or other regime threats) and limited state capacity outside of their capitals.

Yet if it wants to be a constructive development partner to African states, China can no longer hide behind its non-interference policy. Economic development is as political as it gets. Any constructive partner in that effort necessarily has to invest in knowing and appropriately responding to host political economies.

Simply assuming that every public official has a price is a surefire ticket to ruin. Instead, understanding the intricacies of domestic institutions and politics would unlock opportunities to tie the hands of African elites in a manner that avoids some of the pitfalls highlighted above. For example, availing contracts to legislatures (as required by law) could mitigate unsustainable overpricing of infrastructure projects and boost China’s image as a responsible development partner.

III. Conclusion

Sino-African relations have a long history and promising future. So far in this century, China has been a net positive influence on economic development in Africa. However, if the relationship is to remain on a positive footing, Beijing needs to make a number of adjustments based on lessons from the last twenty years. I have proposed that the adjustment include actively helping African countries build effective bureaucracies, investing in African agriculture, incorporating African links in Chinese value chains, expanding investments in African human capital, and cultivating a more sophisticated understanding of African politics.

Finally, I should note that the rise of personalist rule in China under Xi Jinping’s likely life presidency is a source of uncertainty about Sino-Africa relations. However, I have (moderate) confidence that the Chinese political system will remain stable, and that Africa will continue to be a core part of China’s global geopolitical ambitions. This reality presents a great opportunity for African leaders to build partnerships with Beijing focused on improving the livelihoods of their populations.

Ken Opalo is an Assistant Professor in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University and the author of Legislative Development in Africa: Politics and Postcolonial Legacies. (You can download the book’s introduction here.) Read more by Ken Opalo at An Africanist Perspective, which treats the political economy, international affairs, and culture of Africa. The Cosmopolitan Globalist warmly and gratefully thanks him for contributing to this Africa Week series.

Claire—the hyperlinked article reminds me that I’ve also written about the methodological difficulty, and the importance, of properly measuring corruption.

Ken—See also my earlier discussion of the way African countries ought to approach their engagements on the global stage, including with China.

Claire—we’ve previously discussed China’s demography and its implications, for example in this essay exploring the work of Peter Zeihan. I now wish I had thought to ask Zeihan whether he imagined it possible for China to outsource its labor requirements to Africa, develop a massive African market, and thereby escape the effects of its demographic crisis (and thus avoid the economic and political collapse he predicts).

Now if only the West would wise up before Xi’s replaced by a Deng!

Ken,

Why aren't the graduates at the at the School of Foreign Service where you teach influential enough to implement a change in US policies toward our aid to Africa? I assume many of the current administration of USAID are graduates of your school? Why no new thinking on making US aid more effective?