The Flight from Reality

What do Jordan Bardella, Joe Biden, Donald Trump, and Brexit have in common?

They called Michael Heseltine “Tarzan” back when he was Margaret Thatcher’s Secretary of Defense. He’s 91 now. Only he was willing to say it plainly:

We’re facing the most dishonest election campaign of modern times. Because both major parties have got one obsession, and that is to keep the real debate out of … the subject of Brexit. And you can’t have a discussion about the country’s economy, or its defense, or immigration, or the environment, and not discuss Brexit. I mean, we have cut ourselves off from our principal market, our most important partners. And that is the underlying crisis that faces this country. And it’s terrifying to me that whilst public opinion is moving, and the younger generation is frustrated, the two major parties think they can go through six weeks of campaigning and not have anything to say about it.

The party leaders avoided the word and the topic so scrupulously that an anthropologist would have surmised it a religious taboo. The deeply isolated people of this small island believe the utterance of the word “Brexit” will cause crops to fail and women to miscarry. In the few sentences where the word “Brexit” appears in the Conservative Party’s 76-page manifesto, it is meaningless: “And to protect our pubs, we will maintain our Brexit Pubs Guarantee … ”

The language of Labour’s manifesto is carefully calibrated. It is meant to be read by someone who knows, far below the level at which he can verbalize it, that Brexit did catastrophic damage, not just to the British economy, but to Britain’s place in the world, its power, its security, and its reputation for being a stable and well-run country full of sensible people. Someone who knows, very deep down, that it was a stupid, reckless decision, made in a fit of pique, for ignominious reasons; that he was sold a bill of goods by hucksters who used him to further their own ambition; that his life is harder, and his children’s lives will be harder, because he fell for a con as obvious as an email from the Nigerian Minister of Petroleum. It is meant to be read by someone who grasps, in a primitive and preverbal way, that he should have known, because someone was promising him money for nothing, which isn’t the way the world works, and because everyone warned him what would happen.

The manifesto is not written plainly enough to bring these thoughts to conscious awareness. People who’ve done great damage feel shame. People you’ve made to feel ashamed won’t vote for you. The word “Brexit”—the primary legacy of the Tory’s fourteen years in office— appears in the manifesto only once.

Instead, the language of the manifesto makes the argument—aimed, again, at the parts of the reader’s mind that are unconscious and unverbal—that voting for this unexciting version of Labour, led by sober, responsible Keir Starmer, will make things right and be an atonement. The section on foreign policy is titled “Britain Reconnected.” (My emphasis.) The “darkening global landscape,” it says demands “a strong and connected Britain.” Under Labour, the UK will be “a leading nation in Europe once again.” No plan for this is offered, because it can’t be done. Labour “will work to improve the UK’s trade and investment relationship with the EU, by tearing down unnecessary barriers to trade.” It says nothing about how those barriers got there.

Then the word Brexit makes its single, lonely appearance: “But to seize the opportunities ahead, we must make Brexit work.”

This implies, obviously, that it did not work.

There are the explanations voters give to pollsters when asked to account for their political choices. Then there is the unconscious agenda. I once thought that the former must be quite important. But in the past decade, I’ve seen so much evidence that the vast majority of voters don’t care at all about policy or ideology that I’ve concluded otherwise. Almost all of the language we use to discuss politics—all discussions of policy, the economy, taxation, legislation—is a smokescreen for a very different psychological agenda. That agenda is largely unconscious. None of what people say about why they prefer one candidate to another is true. Politics, in a democracy, is about giving voters what the deep, unacknowledged part of them longs for while simultaneously providing them with a political language they can use to justify that choice.

The relationship between a people and their leader is a profound one, psychologically, and this is where the action is really taking place. If you accept this, you can understand why it was possible for the GOP to embrace a candidate whose proposals amounted to a formal contradiction of every precept the party had long espoused. When in 2020 the GOP declined to publish a platform at all, I realized that I’d spent my life profoundly misunderstanding politics in democracies. An election is not about the issues. It isn’t won by the party with the most promising scheme for health insurance or the candidate whose ideas for lowering energy costs sound most feasible. It’s about the Superego and the Id.

I’ve written before about the political scientist Shawn Rosenberg, who in 2019 scandalized the annual meeting of the International Society of Political Psychologists by presenting a paper in which he made the case that democracy was devouring itself. “In well-established democracies like the United States,” he concluded, “democratic governance will continue its inexorable decline and will eventually fail.” Here’s the abstract:

In many of the established democracies of Europe and North America, populist alternatives to democratic governance are gaining popularity and political power. In attempting to make sense of these developments, I argue, unlike many, that the rise of populism is not simply a passing response to fluctuating circumstances such as economic recession or increased immigration and thus a momentary retreat in the progress toward ever greater democratization. Instead I suggest current developments reflect an underlying structural weakness inherent in democratic governance, one that makes democracies always susceptible to the siren call of right-wing populism. The weakness is the relative inability of the citizens of the modern, multicultural democracies to meet the demands the polity imposes upon them. Drawing on a wide range of research in political science and psychology, I argue that citizens typically do not have the cognitive or emotional capacities required. Thus they are typically left to navigate in a political reality that is ill-understood and frightening. Populism offers an alternative view of politics and society which is more readily understood and more emotionally satisfying. In this context, I suggest that as practices in countries such as the United States become increasingly democratic, this structural weakness is more clearly exposed and consequential, and the vulnerability of democratic governance to populism becomes greater. The conclusion is that democracy is likely to devour itself. In the hope that it may not, I briefly consider the kinds of institutional changes that are necessary to facilitate the development of the citizenry democracy requires.

I wrote about Rosenberg’s thesis at the time:

I took his argument seriously. I conceded there was evidence for it. But I thought the verdict remined out. “I still expect Trump to leave,” I concluded, “when citizens vote him out.”1

(You won that round, Shawn.)

Brexit is not the only reason that Britain has lived through years of economic immiseration and political dysfunction. But it is the biggest reason.

Britain has now experienced two lost decades. Real wages in Britain still haven’t recovered to pre-2008 levels. If wages had kept pace with pre-crisis trends, the average UK worker’s wages would now be at least £10,000 higher.

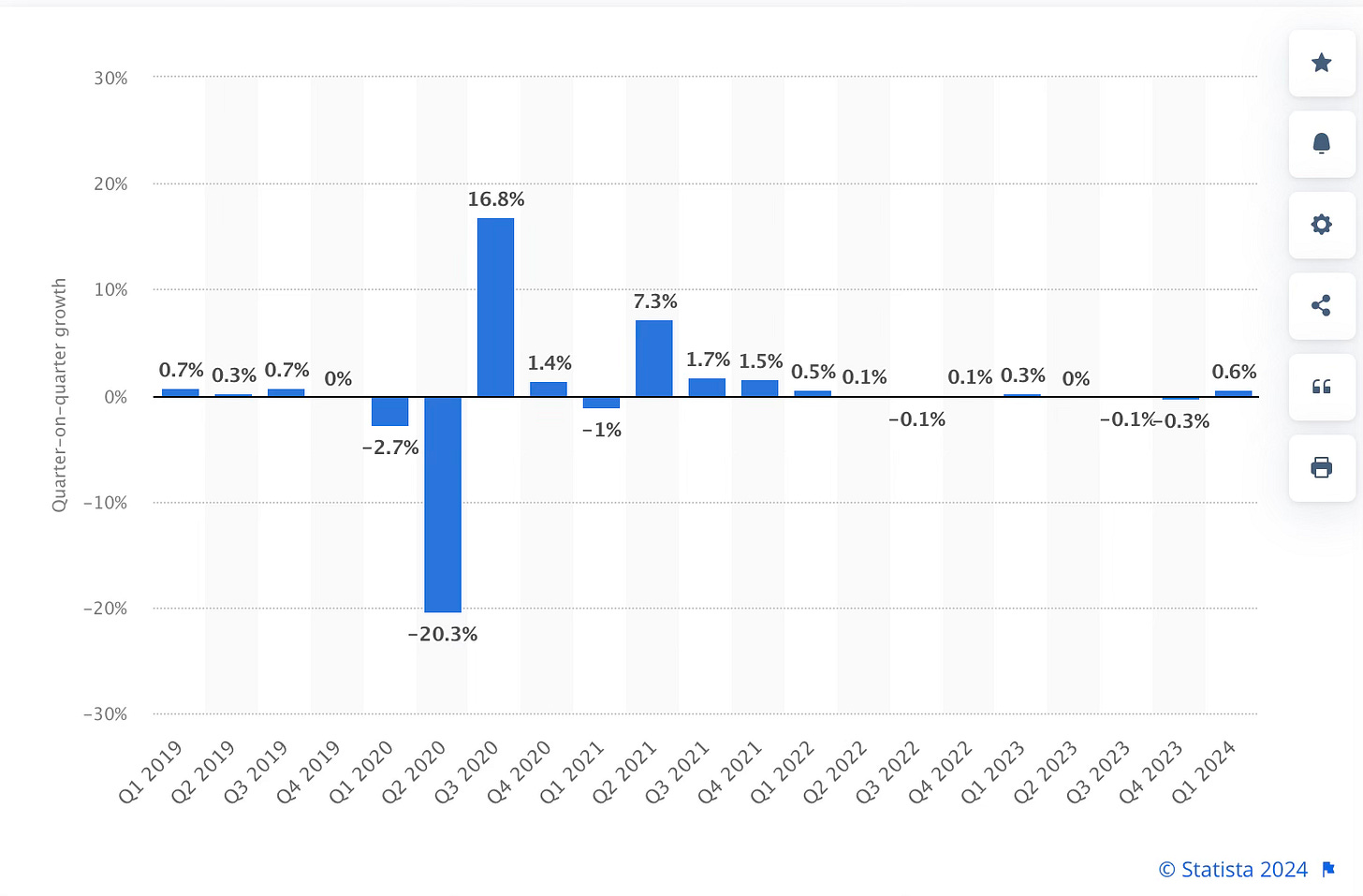

This stagnation was one of the reasons Leave won. But if the economy was underwater before, it is now on the sea floor. Britain experienced almost nothing by way of post-pandemic recovery. It has had the highest inflation and lowest growth in the G7.

Since the pandemic, US growth has averaged 3.8 percent. Perhaps owing to the impact of inflation, Americans remain persuaded their economy is terrible—in a recession, even. But British growth has been 0.4 percent—the lowest since the 1920s—and it has been suffering from far more severe inflation. The British are right to think their economy is terrible.

The precise economic impact of Brexit on the UK economy is hotly disputed, and not just because the question is so politically contentious. It’s difficult to disentangle the effects of Brexit from the effects of the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, and domestic economic policy. In January, Cambridge Econometrics published a study commissioned by the Mayor of London. It’s a serious effort. They compare the UK’s economic forecast now to one in which it had stayed in the EU. By 2035, they conclude,

GVA (gross value added, the measure of the value of goods and services produced in a given sector) will be 10 percent lower in the UK and 7.5 percent lower in London.

The UK will have 3 million fewer jobs, of which approximately 500,000 would have been in London.

The UK will have 32 percent less investment, leading to lower output.

Imports will be 15.8 percent lower; exports will be 4.6 percent lower.

London’s productivity will remain about the same, but GVA and employment will fall.

London’s economy is more resilient and will be less damaged by Brexit than the rest of the UK. But the gap between London and the rest of the UK will widen even further.

Brexit will have a negative impact on every sector of the economy.

The largest negative effects will be in the construction sector, whose value in 2035 will be 31.7 percent less than it would otherwise have been. The value of manufacturing will be 17.4 percent less. The value of British agriculture will shrink by almost 15 percent. The effects on employment in those sectors will be commensurate.

Other studies have come to different conclusions, but not one serious study concludes that Brexit has proved or will ever prove a net gain for any major sector of the economy.

Consider the table below:

By 2019, UK banks had transferred more than US$1 trillion out of Britain. New investment in the UK from Europe had declined by 11 percent.

London’s economy alone has shrunk by more than £30 billion. The UK’s trade in goods has fallen by 10 percent since 2019, while that of the other G7 countries has risen by 5 percent. Middle-income households in the UK are now 20 percent poorer than those in Germany and 9 percent poorer than those in France. The low-income cohort is 27 percent worse off than its counterparts in both countries.

Voters wanted to stick it to their loathed urban elites, and they did. But above all, they stuck it to themselves.

The Leave campaign promised Britain would be flush. It would use the money it saved by not contributing to the EU for underfunded government services like the NHS. Nothing of the sort has occurred. None of the promises—higher wages, more money, shorter wait times to see a doctor—have come true. Not only did British public services fail to receive that cash infusion, they’ve in many cases stopped working. The new trade deals Britain has signed come nowhere near compensating for the loss. The big prize—a trade deal with the United States—was never in the cards. (Obama told the British people the perfect truth about that.)

Even the promise of fewer immigrants was a lie. Or perhaps especially that promise. To prop up the British economy, the government concluded it had no choice but to massively increase immigration. The number of new arrivals since Brexit dwarfs all previous influxes. In the three years before Brexit, according to the UK’s Office for National Statistics, 836,000 people migrated to the UK. In the past three years, 1.9 million have arrived, as Sky host Beth Rigby reminded Rishi Sunak in this interview below. (On confrontation with these figures, he seemed to forget that he was the prime minister.)

I don’t know why he missed the opportunity to explain why immigration has been rising. Two categories of immigrants account, almost entirely, for the rise. The first are students; the second are health care workers. As in every developed country, the British are living longer and having fewer children. An elderly population requires a lot of medical care. Likewise, as in every developed country, more and more people are seeking university degrees. (This is in some measure because societies are growingly more technologically complex.) Foreign students, who pay more in tuition, subsidize the tuition of British citizens. When the economy slows or stalls, as the British economy has, politicians have a choice: They can cut public services, or they can use lower-cost immigrant labor to staff the NHS and higher-fee immigrant tuition to keep universities affordable. Why these tradeoffs are so hard for politicians to explain and voters to understand, I have no idea: The ideas aren’t complex; in fact, they’re quite intuitive. But voters don’t understand. They believe politicians are drowning them in immigrants and skimping on their health care out of malice.

Without immigrants—not just doctors, but nurses, home care aides, audiologists, hospice workers—the NHS would collapse. The NHS, for the British, is non-negotiable. Nearly four out of five British citizens agree with the statement, “The NHS is crucial to British society and everything should be done to maintain it.” Without foreign students, British universities would collapse, or become so expensive only the very wealthy could attend them. When Britons who haven’t produced 2.2 children complain simultaneously that there are too many immigrants and that the wait times to see a doctor are too long, they are expressing a desire for reality to reconfigure itself. It won’t.

In Britain’s case, the rise in immigration is the direct consequence of Brexit. Losing access to the EU’s massive market was (predictably) harmful to the British economy. Slower growth (predictably) entails less money for public services. The public’s unwillingness to accept cuts in public services means (predictably) that politicians must find a way to make up the shortfall.

It’s true that as promised, leaving cut down on the number of migrants from the EU. They’ve been replaced—and then some—by migrants from Asia and Africa. That is not what the British thought would happen when they voted “Leave.” (I must say this gives me a modicum of satisfaction: Just who did they imagine would change their bedpans?)

The plan to rip page after page of EU regulations from Britain’s statute books has been abandoned. Those faceless European bureaucrats, it turned out, were quite good at writing regulations, and you do need regulations, after all. No one in Britain was keen on seeing what happened to the airplanes without them.

Years of political turmoil ensued as politicians argued about how to implement the referendum without committing economic seppuku, or touching off a fresh war in Northern Ireland. It has left the UK bitterly divided and exhausted. All of this should have been predictable to voters. But they so badly wanted to believe Britain’s problems had a simple cause —“experts!” “elites!” “globalists!” “faceless EU bureaucrats!”—and an easy fix that they allowed themselves to be seduced by Boris Johnson—a man whose every word and gesture screams, “I smash up things and creatures and then retreat back into my money or my vast carelessness or whatever and let other people clean up the mess I’ve made.”

The Wall Street Journal reported recently on the Brexit backlash. They spoke to one Anton Dani, himself an immigrant, who voted Leave:

… He wants a more competitive Britain and likes immigration but thinks that too many people enter the UK to take advantage of government benefits. Today Dani says he is angry. Migrants have continued to come from Europe to [the British town of] Boston, he says, pointing to a group of Romanians walking past his cafe. Life in Boston meanwhile hasn’t noticeably improved, he adds. “We have achieved nothing,” he says. “You learn what you already knew: That politicians are liars.”

Memories do get short, don’t they. Who exactly forced this on him? He voted for it. Does he not remember the politicians who warned him this was a bad idea? So much did the government respect his crummy decision that they carried it out even when it dawned on them that the consequences of it would be so terrible that if nothing else, they were sure to find themselves booted out of office.

Yes, some of the politicians were liars. But it’s not as if he lacked the information he needed to recognize this. Do you remember Michael Gove’s famous interview? Perhaps not: Everyone knows the infamous soundbite, but many may never have seen it in context:

Faisal Islam: The leaders of the US, India, China, Australia, every single one of our allies, the Bank of England, the IFS, the IMF, the CBI, five former NATO secretary generals, the chief exec of the NHS, and most of the leaders of the trade unions in Britain all say that you, Boris, and Nigel are wrong. Why should the public trust you over them?

Michael Gove: I’m not asking the public to trust me, I’m asking the public to trust themselves. I’m asking the British public to take back control of our destiny from those organizations, which are distant, unaccountable, elitist, and don’t have their own interests at heart—

Islam: Elitist? Elitist?

Gove: Absolutely.

Islam: The Lord High Chancellor, a conspiracy of elites? That’s like something out of Wolf Hall—

Gove: Well, I haven’t seen Wolf Hall, but but the one thing that I would say is that the people who are backing the Remain campaign are people who’ve done very well, thank you, out of the European Union, and the people, increase—

[The audience bursts into spontaneous applause. Gove looks pleased with himself. Islam tries to interject, but Gove is on a roll]

—absolutely, and the people who are arguing that we should get out are concerned to ensure that the working people of this country at last get a fair deal. I think the people in this country have had enough of experts with a—

Islam: (incredulous) —Had enough of experts? The people in this country? Had enough of experts? What do you mean by that?

Gove: —from organizations with acronyms saying that they know what is best and getting things consistently wrong. Because these people—

Islam: This is proper Trump politics, isn’t it.

Gove: No, it’s actually a faith in the—

Islam: It’s a faith.

Gove: British people—

Islam: Blind faith.

Gove: —to make the right decision.

Islam: This is Oxbridge Trump.

Gove: I don’t think it is, because one of the striking things about this debate is that those who are arguing that we should remain have a vested financial interest—

Islam: Ah, right. So are they lying, are they stupid, or is there a conspiracy? There’s a conspiracy.

Gove: No, I’m pointing out that the majority of people in this country are suffering as a result of our membership of the European Union.

Islam: The majority?

Gove: Their wages are lower—

Islam: The majority of people?

Gove: Yes. Their wages are lower and their access to—

Islam: —33 million people?

Gove: —public services is restricted—

Islam: What’s your factual basis for the claim that 33 million people in this country are suffering from EU membership? You complain about the other side’s figures. What’s your factual basis for the claim that the majority of people in this country are suffering from EU membership?

Gove: Well—

Islam: You don’t have one, do you.

Gove: Well, I know myself, I know myself from my own background, I know that the European Union depresses employment and destroys jobs.

Islam: You have’t got a majority, have you.

Gove: My father had a fishing business in Aberdeen destroyed by the European Union and the common fisheries policy.

Islam: That’s one person.

Gove: The European Union has hollowed out communities across this country, which, and it has also contributed to lower salaries for working people, and it has also ensured that young people in this country don’t have the opportunities to get the entry level jobs that we heard about last night. Now you can say that their concerns don’t matter—

Islam: —I didn’t say that. I didn’t say that.

Gove: You can dismiss concerns—

Islam: I did not dismiss it. You said a majority—

Gove: You were dismissing my father—

Islam: I didn’t dismiss it. You claimed that your example—

Gove: You were dismissing the claims of working people—

Islam: I did not dismiss it. You claimed—

Gove: You’re on the side of the elite. I’m on the side of the people.

There you go. Pure populism.2

It’s true that Gove is from a working-class background, by the way, very up-by-his-own-bootstraps, so that’s not a complete pose. But at the time he said this, his net worth was assessed at £1.6 million. (How he amassed that on a ministerial salary isn’t obvious to me.) His views about Brexit were entirely a matter of personal ambition; he came to them when he calculated that if Leave passed, Cameron would have to step down, meaning the job would be vacant. So he betrayed Cameron and began campaigning for Leave. When Rishi Sunak called the election that he just lost, Gove announced he wouldn’t stand. “A new generation should lead,” he said.

Anton Dani cannot claim he had no way to discern the truth. Any man who didn’t long to be lied to would have known full well which one of those men was telling it. When someone like Gove says, “I’m on the side of the working class and you’re on the side of the elites,” hide the silverware.

Plenty of politicians told Anton Dani the perfect truth, as plainly as possible—as did the leaders of the US, India, China, Australia, every single one of Britain’s allies, the Bank of England, the IFS, the IMF, the CBI, five former NATO secretary generals, the chief exec of the NHS, and most of the leaders of the trade unions in Britain. As did Keir Starmer, for that matter. Which is why he’s now the prime minister.

So here is Britain, once the seat of an empire on which the sun never set. By virtue of its geography and demography, it will always be highly reliant on food imports, immigrant labor, and access to export markets. Just 23 miles away lies the world’s biggest and most successful trading bloc and single market. It used to be Britain’s main trading partner, accounting for half of its trade, offering British businesses 420 million customers and no barriers to reaching them, plus a labor pool of 150 million educated people at every level of skill. Food and goods were freely importable and exportable without paperwork or tariffs. Every British citizen could travel, study, work, and reside anywhere in Europe, in the most desirable places to live in the world. Britain even had a special deal with the EU, enjoyed by no other country, allowing it to keep its own currency and enjoy the EU’s benefits on more favorable financial terms. What kind of lunacy persuades people to insist that their biggest trade partners impose tariffs on them? Who votes to impose sanctions on themselves?

The British voted for Leave because they didn’t care to think about basic economics, didn’t understand what the EU was, and didn’t care to learn. They were suckered by Nigel Farage, and in a moment of foolish impetuousness—out of the resentful impulse to punish the elites—they overnight turned Britain into an isolated and dreary island with a crummy economy and no influence.

Here is the former chief of MI6, Sir Alex Younger:

… Particularly since I’ve left office and I’ve travelled around Europe, I’m profoundly depressed. Just nobody mentions the UK. We’ve made ourselves irrelevant. And this is extraordinary. The beginning part of this century, we were the dominant force. France has effectively eclipsed us, and you just don’t hear a discussion of us. I think Brexit has marginalized us. It was kind of intended to do exactly that. …We’ve got NATO, and NATO is great, but conflict is about so much more than war, now. It’s in the economic and tech space, and the digital and data, and that’s all civilian—and we just marginalized ourselves. So Putin will have been absolutely delighted by our decision, as will Xi Jinping.

When polled, only 10 percent of the British public say that Brexit is “going well for now.” Only 15 percent say the benefits of leaving have outweighed the costs, and the only reason that number isn’t lower is that it’s so difficult, psychologically, to admit one has been a fool. It is a perfect example not only of the shallowness of populism, but the cost.

So if you were a French voter, looking at Britain, what lessons might you draw from this?

“My God, that is tragic. Those poor people. Let us send them humanitarian aid and pray we are never tempted by such a mistake.”

“Too right, you’ve been eclipsed! Let us enjoy our newfound power and influence!”

“Wow, how can we do that to ourselves? Wait, British friends! We want to be impoverished and irrelevant too!”

I won’t keep you in suspense. You probably guessed where I’m going with this, anyway. The French have decided that Door Number Three looks especially exciting.

No, I don’t get it, either. The UK is only a short hop away, but it may as well not exist for all the French have learned from its experiences. In fact, you’d think Macron was studying the life and works of David Cameron every night by candlelight, so perfectly did he devise a scheme to reprise Cameron’s self-destruction. The impulsive gesture, the recklessness, the idiotic miscalculation, the vanity, the way he cloaked his gamble in lofty rhetoric about letting the people choose—even the look on his face when he realized that (for the first time in his life) he wouldn’t be able to cleverly talk his way out of the mess he’s made.

The French are on fire to drag themselves further down than the British, so assiduously are they repeating their mistakes. Both the far-right and the far-left have told the French exactly the same lies that the British heard from Nigel Farage. They’re making the same promises of magic money that will grow from the ground like sunflowers on Chernozem once France tells the EU to piss off and gets rid of the immigrants (populist porky: far-right variant) or tells the EU to piss off and soaks the rich (populist porky: far-left variant). If you don’t see magical money trees growing from the ground, it can only be because the immigrants and the bankers are stealing them. Obviously.

France has now committed to one of three paths: far-right, far-left, or chaos—or perhaps one of the above and chaos.3 In a few hours, we’ll know which flavor of unnecessary suffering is coming, but we already know unnecessary suffering is on its way, just as the people demand.4

Again, there’s a text and a subtext. The text is immigration and the cost of living, but the subtext is impulsiveness, resentment, envy, and the sincere desire to be told lies. The French, like the British, are determined to ignore every sober voice saying, “That won’t work,” “That will cause more problems than it will solve,” “That’s not a good idea,” “That’s a very bad idea, actually,” and “This is going to completely screw you up, and for a good long time, at that.” They’re dismissing sobriety as the purview of elites and experts and globalists (and we all know what they mean by that). They’re trampling over each other to throw themselves into the embrace of politicians who make magical promises about all the nice things they’ll have if they just believe in something insane.

I’ve read in a number of American outlets that the far-right is performing as well as it is here because centrist politicians have failed to control immigration. But in January, with the help of the far-right, Macron passed an immigration bill so restrictive that the Constitutional Court had to strike parts of it down. The only way Macron could be tougher on immigration is by changing the Constitution, which does not pose an impossibly exigent standard. He gave the far right everything it asked for except tossing out the Constitution, and he tried.5 If French hides were so chapped by the laxity of France’s immigration laws, that should have been enough to mollify them. Macron, in effect, said to France, “There’s no need to vote for the extremists, because I’ll give you what you want and you won’t have to embarrass yourself by voting for a party whose members keep turning up in viral videos wearing SS memorabilia or calling their neighbor a bonobo.”

In English:6

But it turned out that his critics on the left were right. Instead of mollifying the far-right’s voters, it legitimized their agenda. It seems that if you want far-right policies and you’re not embarrassed to say so, you’ll vote for the real thing, especially because the RN promises to get rid of the immigrants and lower the retirement age back to where it was before Macron started lecturing everyone about his latest woke obsession, “the debt.”

They say it will all be paid for by the savings France will incur when the immigrants stop leeching off the real Frenchmen. Also, they’ll lower your taxes more than Macron would. And spend more on all those government services everyone likes. (More health care. Bigger pensions. Cheap gas. Longer vacations More subsidies!) No wonder the French prefer them, right? There will be endless money and happy times once the immigrants are sent à la niche. Plus, no more woke, condescending lectures from bien-pensants like Macron about “the budget.”

His final act of insanity apart, Macron has done a good job. Even a very good job. France was making progress in ways I hadn’t seen here before.

The Economist recently published an article titled, “Is the revival of Paris in peril?” “The French election,” says the sub-heading, “threatens a remarkable commercial renaissance.” Under Macron, they write, Paris has undergone “an astonishing revival.” A city synonymous with bureaucracy, taxation, and employees who couldn’t be fired has become a world leader in finance and tech. Macron ensured that Paris, not Frankfurt, would be the chief beneficiary of the stampede out of London.

Macron is pro-business. He has insisted upon a predictable and friendly climate for investment. But as the Economist concludes, “This business-friendly approach may not survive the parliamentary election.”

This, not immigration, is the source of so much of the anti-Macron passion. He’s made the rich richer. There’s no evidence he’s made the poor poorer. To the contrary, youth unemployment has declined steadily under his watch even though his government phased out subsidies for entry-level jobs. Unemployment, overall, is lower now than it was under Chirac, Sarkozy, or Hollande; and this is true for workers at all education levels.

But making the rich richer—that was unforgivable. Macron is endlessly criticized here for being a banker. Bankers everywhere are endlessly criticized for all the usual reasons. But this is ridiculous: It’s been 35 years since the fall of the Berlin Wall. France’s deep aversion to banking is an absurd anachronism. Macron is called, by the far right and left alike, “The president of the rich.” They would prefer that everyone be poor than anyone be rich.

When Macron called the election, the markets tanked. France is one of the most indebted countries in the EU. Its deficit, at 5.5 percent of GDP, is the EU’s fourth largest. The government borrowed a lot to keep the country afloat during the pandemic, which was the right thing to do. But the pressure on public finances leaves France at the mercy of its creditors.

Le Pen’s budget would add €71 billion to the deficit every year.7 Everything she says she’d spend it on sounds great. Who wouldn’t like higher salaries for teachers, smaller classes, more money for health care, and exemptions from income tax? Who wouldn’t like subsidized jobs for students? Better salaries for doctors and nurses? More judges, more magistrates, and only French food in the canteen—it sounds swell. The problem is that even if she implements every single measure she proposes to prevent immigrants from using France’s social services, the savings would only amount to 9 percent of all her new spending.8

Not to be outdone, the left-wing coalition plans to raise the minimum wage, fix the price of household goods, fix the price of energy, make school free, spend more on low-cost housing, lower the retirement age, repeal Macron’s immigration reform, invite “climate refugees” to France, and raise the deficit by €179 billion per year. They’ll pay for this by soaking the rich. (This tax will have a “climate component.”) But won’t the rich just take their money somewhere else? Oh, but those clever monkeys have thought of that: That’s what the “exit tax” is for. As the Montaigne Institute writes, “no economy could sufficiently compensate for the costs incurred by these measures.”

Macron’s coalition proposes to reform France’s unemployment insurance system and introduce a complementary health insurance scheme to cover expenses that aren’t reimbursed under the current arrangement. Its plan will cost €21 billion per year, says the Institut Montaigne.

Both sides of the French spectrum are furious at Macron for raising the retirement age to 64, even though it was a long-overdue and obvious measure. French life expectancy has soared in the past half-century. This is the kind of problem one is lucky to have. I wrote about France’s response to the proposal to do so:

The other night, in a televised debate with Prime Minister Gabriel Attal and National Rally leader Jordan Bardella, Manuel Bompard, who leads the list for the far-left LFI, promised to lower the retirement age again (as did Bardella). Macron’s government, Bompard said, “stole two years of your life.” The audience thought those words made perfect sense. This says a great deal about how the French conceive of themselves in relation to the state, how they imagine the economy works, and who they imagine the President to be.

They hate Macron, too, for loosening France’s labor regulations, which so badly needed loosening that I knew of a firm with an incompetent employee who hired her replacement without firing her because it was cheaper and less bureaucratically arduous just to keep her on the payroll. Macron fixed that, Alhamdulillah. Laws like that caused stubbornly high unemployment, especially among the young. Reforming them worked. Unemployment dropped. This alone was a huge achievement. No French president had been able to do that before. But the French can’t forgive him for it.

It is dispiriting to watch. Alea iacta est. No matter who wins, France will be poorer, less stable, and less relevant—because voters here are resentful that Macron didn’t meet their emotional needs.

As for those needs, they are complex. Let’s look at the personalities involved.

Emanuel Macron became the president of France at 39, making him the youngest president in French history. Good looking and polished, he is an Énarque—a graduate of the highly selective École nationale d’administration, which prepares the crème de la crème of the French civil service. After his career an an investment banker, he became the minister of economics under François Holland. He betrayed Hollande, founded his own political party, and won the French presidency, even though he had never before so much as stood in an election. He conveys a profound inner conviction that anyone who hasn’t done likewise is just lazy.

Macron is married to his high-school drama teacher, who is 26 years his senior. They became involved when Macron was 15 and she was 40. Everyone in France professes to care not one whit about this and secretly thinks this is weird beyond words.

The French complain that Macron is arrogant and aloof. It’s true that he’s not much for feeling your pain or for backslapping and glad-handling:

(“Manu” is Macron’s nickname. Look how crestfallen that kid is. Macron probably turned him into a Trotskyite.)

Me? It would never occur to me to think about Macron’s social skills if people weren’t constantly telling me how much he offends them. Is he reminding Putin that France, too, has nuclear weapons? Is the garbage being picked up? That’s good enough for me. But I already have a father. I don’t need the president of France’s approval.

Perhaps the hatred of Macron has something to do with his youth, his wife, and his apparently strange sexual tastes. In 2018, I wrote about the very bizarre Benalla Affair. The scandal, which for a time mesmerized France, involved the man in the helmet, below, whom you see enthusiastically beating the snot out of a protester:

The scandal is that the man was 26-year-old Alexandre Benalla—who was not a police officer but one of Macron’s closest advisors and his deputy chief of staff, or perhaps his aide, or his bodyguard, or his driver, the account kept changing. I’ll quote myself:

One thing is perfectly clear: Nothing could keep them apart. France has seen photo after photo of Macron and Benalla skiing together in the Pyrénées and cycling in matching pastels at the seaside. Benalla had the keys to the presidential couple’s home. He was installed in a sumptuous apartment on the Quai Branly with a certain historic significance—it once housed President Mitterrand’s illegitimate family—and paid a salary grossly disproportionate to his role, whatever it was.

The scandal grew worse. Benalla had vague ties to the Russian mob. He used diplomatic passports to which he wasn’t entitled. More videos surfaced. There was, inevitably, an attempt at a cover-up; and while it wasn’t worse the crime, it certainly didn’t help. Jean-Luc Mélenchon described the events as “worse than Watergate” and his parliamentary group submitted a motion of no-confidence, which didn’t succeed because Macron’s party held the majority.

No one ever spoke publicly about the most unsettling part of the story. As I wrote:

… France was ready for a President who married his high school drama teacher; France was ready for a closeted gay President, if that’s in fact what he was, or even an openly gay President. But no, France was not ready for a closeted gay President with a taste for S&M.

In retrospect, I’m not sure that France was ready for a President who married his high school drama teacher or a closeted gay President, either. The scandal probably made it impossible for many in France ever to see Macron in quite the same light.

Voters may not care about policy, but they care very much how a candidate makes them feel. Macron makes them feel ignored, demeaned, and furious. They see that glittering coldness in his eyes and they suspect that he wants to punish them. That he would enjoy it.

Two more protagonists in this psychodrama are worthy of remark. Gabriel Attal recently became, at the age of 34, not only the youngest prime minister in the history of the Fifth Republic but the youngest prime minister in the world. He’s also France’s first openly gay prime minister. Good looking and polished, he comes from a wealthy, bourgeois family. He went to the best schools in Paris. In 2017, he became a junior minister for education, making him the youngest person to serve in the French government. Last January, he replaced Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne, a grey and beleaguered technocrat. I wrote about his appointment here:

… he has no experience of anything. He has never served in the military, never been to sea, never built a company, never been an industrialist, never raised a family, never studied a difficult subject, and never had a job other than politics. Born to the Paris elite, he joined the Socialist Party before he was old enough to vote. Directly after receiving his master’s degree—in public affairs, natch—he embarked upon his political career. Since then, as far as I can tell, he has done nothing but fetch coffee for powerful people, write their speeches, run for political office, and set records each time for being the youngest and most openly gay person to win.

Since then, I’ve revised my opinion. He’s been doing an excellent job. He’s been campaigning indefatigably in the effort to clean up Macron’s mess. Macron destroyed his political career, but he has dutifully kept up with his job and stayed on top of his brief. He consistently shreds his opponents to pieces in debates.9 He is always, obviously, better-informed.

He still comes across to me as too young—there is something overeager about him, even manic—but I sleep fine knowing he’s running things and I will soon miss that.

Now consider Jordan Bardella, who in 2022 was named president of the National Rally. Marine Le Pen’s protégé will be France’s prime minister if his party wins the majority it’s seeking. He will be, at 29, the youngest prime minister in the history of France.

Good looking and polished, he is the only child of Italian immigrants. His father abandoned the family when he was an infant, and he was raised by his mother in a public housing tower on the outskirts of Paris. He says his youth in Saint-Denis was grim: He grew up amid squatters, drug dealers, “seven year-old girls with a veil on their heads leaving the Koranic school,” men who would “slit your throat over a cigarette,” and terrorists. He tells voters that he is running for office to ensure that the rest of France doesn’t turn into Saint-Denis.10

At some point in his student career, Bardella met personalities from the union defense group, or GUD, the far-right student movement described in a 1993 police report as France’s “most virulent formation currently, whose ideological emptiness is matched only by its unbridled propensity to violence.” The leader of the GUD was Frédéric Chatillon. (We’ve introduced him previously.) Bardella became involved with Kerridwen Chatillon, his daughter.

This is how he was discovered by Marine Le Pen, since which point he has lived and breathed far right politics. He was 16. Her eye was superb. She called him her “lion cub,” and sent him for media training.

Le Monde tracked down the former journalist and communication coach who polished him from lummox to luminary. The party had just changed its name from the “front,” suggesting confrontation, to the softer “rally,” which is more like “gathering.”

When Pascal Humeau began coaching Bardella in 2018, Bardella was 22. He struck everyone as their ideal son-in-law. He was the perfect vehicle for the party’s de-diabolization. At the beginning of his training, Humeau has said, Bardella was “an empty shell. He didn’t read books, nor the press, doesn’t inform himself.” He was a machine into which Marine’s language software could be programmed. Humeau taught him to smile. It was a challenge. (His nickname was “the cyborg.”)

Bardella was particularly valuable to Marine because he came from a working class background, and the working class is her party’s base. Humeau takes credit for Bardella’s favorite stump-speech vignette about the drug dealers who would “slit your throat for a pack of cigarettes.” Details like these, he said, “humanized the cyborg.” Meanwhile, Bardella became deeply devoted to Jean-Marie Le Pen. Perhaps the patriarch was a father figure to him.

A regional Paris councillor by the age of 20, then head of the party’s youth wing, Bardella dropped out of college to focus on his political career. At 23, he was designated the leading candidate on the party list. He became vice president of the rebranded National Rally in 2019, and in the same year, became the second-youngest member of the European parliament in European history. There, he systematically abstained from, or voted against, any motion prejudicial to the Kremlin. He did not even vote for a motion condemning Alexei Navalny’s death in custody. “It’s not up to the EU to decide whether one state or another has done the right thing,” he said. “Diplomacy, like the army and defense, is a national matter.”

He did nothing else: He was one of the least productive members of the parliament. Perhaps he was busy with his new girlfriend, Nolwenn Olivier, who is Marine’s niece and Jean-Marie Le Pen’s granddaughter. What brought them together, they say, is their shared passion for cooking.

In 2022, Marine Le Pen installed Bardella as party leader, affording herself the ability to focus her energies on her 2027 presidential bid while Bardella busied himself with the party’s brand metamorphosis. His chief contribution to the detoxification effort was his name, which is not “Le Pen,” and his style, which is calm and sincere, polite without irony. “Our civilization will die,” he says in his speeches, at which teenage girls have been known to faint, “because it will be submerged by migrants who will have changed our customs, culture, and way of life irreversibly.”

It is Bardella’s command of TikTok, above all, that has mobilized France’s youth vote for the far right. He’s perfectly adapted to the medium: smooth, smooth-skinned, even-tempered, comfortable with himself, unburdened by complex thought.

Bardella is as irresistibly charming as Macron is off-putting. A few days ago, my father asked me: “Who does he remind you of?”

I was stumped. “I give up.”

“Same energy,” he said. Maybe. Though Belmondo was older.

Consider how profoundly weird all of this is. The job in question isn’t “actor” or “pop star.” It’s “leader of Europe’s only nuclear power during its worst crisis since the Second World War.” Does this seem like a good idea?

You may, like me, be asking yourself why France is eager to put a boy band’s worth of good-looking, inexperienced young men in positions of utmost responsibility. I haven’t a thing against good looking young men. (Trust me.) But what are they thinking? This can’t be a coincidence. Two, maybe, is a coincidence. But three? Moreover, two of these three men are creatures of a much older and dominant woman, and the third doesn’t fancy women at all. What’s that about?

Like the relationship between Macron and Brigitte, the relationship between Marine and Jordan is immediately, recognizably weird. It’s weird in ways no one ever articulates, because even before the thoughts are fully formed, they’re suppressed. “Such a thought, if I were to have it, would evoke outdated and harmful sexist stereotypes. That’s against the values of the Republic. Therefore I won’t think that.”

France, like the United States, seems doomed to be led by men who are not the right age to be leaders. If France is determined to elect men who look barely old enough to shave, we are determined to elect men who can’t remember the doctor who administered their dementia test. Why? In both cases, there is something being expressed—a profound contempt for reality.

The reality is that men are only suited to that kind of job for a period of about twenty years in midlife—when they are old enough to be mature, disciplined, and experienced, but young enough to be vigorous. There are exceptions at the margins. But they are rare. If you want leadership and statesmanship, pick a man between the age of 45 and 65. Pick someone with a proven record of accomplishment under complex and stressful conditions. Pick, for example, the man who planned Operations Torch and Overlord and then carried them out while serving as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force.

If you’re asked what comes to mind when you think of this man, your first word should be gravitas. It should not be geriatric, gigolo, or gadzooks. Don’t choose anyone whose face makes you stifle a giggle. This is your country, for God’s sake. These people will have the nuclear codes. They are Shiva, destroyer of worlds. This is not a joke.

And yes, nine times out of ten, you’ll pick a man. More men than women are drawn to the top echelons of power, just as more men than women wind up drinking themselves to death in a gutter. As the research (and your own eyes) will tell you, men’s talents are distributed further along the extremes of the Bell Curve. If you’re a woman and this bothers you, you don’t have what it takes to be the President of the United States: This aspect of reality would be the least of your problems on your easiest day, so don’t sweat it.

If you live in the West, the most qualified man will probably be white, because there are more white men than black ones. The reverse is true if you live elsewhere. So when you’re choosing someone to wield that much power, don’t insist that the candidate must be a black woman. This narrows the list of plausible candidates to Kamala and Oprah. If you let white men compete, you’ll have a much better chance off finding a candidate who won’t lose to Donald Trump, and though I like Oprah’s chances, she should not be the President of the United States.

Pick someone with a placid and traditional family life. Pick someone who doesn’t have a shellacked golden weasel where his hair should be. Don’t pick someone who sets any kind of record just by winning the office. If no one before you ever once thought it would be a good idea to put someone that young, that old, or that demented in power, they were probably right. Don’t elect “the first president who married a yak.” Your country doesn’t need a First Yak.

There is no way to win a war on reality. Reality will bite you in the ass every time.

Now if only I could persuade Joe Biden.

By which I meant “voluntarily.” And without trying to stage an autogolpe. I really didn’t see it coming that within five years, the GOP would firmly aver that trying to stage an autogolpe is no impeachable offense, nor should it be a criminal offense, nor should it prevent the golpista from holding office again, and indeed, thinking otherwise is absurd.

If you’re in any doubt about what this rhetorical maneuver signifies, review this:

Update: Looks like chaos. I’m very relieved. This is by far the best of the three. We’ll be ungovernable, but we dodged a bullet.

And why, for the love of God, does France have a proudly-named communist party that can actually win seats in parliament? Didn’t anyone tell them? Marine Le Pen, at least, was smart enough to grasp that some ideas are so bad that if they happen to be your ideas, it’s time to confuse everyone by changing the name of your political party.

Sure, you could probably find some Pétainist freak in a rural hamlet in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur who would make the case that Macron didn’t go far enough because he didn’t mandate drowning any product of racial miscegenation in the Seine. But apart from that, the far right should have been very happy.

I like the way the AI did their voices, but not the translation of the key phrase, “Va à la niche.” Yes, it can be translated as “Go to the doghouse,” but in English that just sounds bizarre, not profoundly offensive. It is, in fact, profoundly offensive in this context. I’d translate it as something like, “Go back into the hole you crawled out of.” (All of France has been debating the phrase “Va à la niche” and what it means that Marine Le Pen insists that no, it’s not offensive and she uses it all the time.)

These numbers will sound like Monopoly money to Americans, but France doesn’t have superpower-privilege. This privilege works out very, very well for Americans and it would be a shame to lose it.

I can reveal to you now, as an immigrant in France, that France already does a damned good job of ensuring that immigrants who take more from the system than they put into it are quickly shown the door. There is no magic money lying on the floor, just waiting for someone to pick it up. This is a fantasy.

I’ve lost count of the number of debates we’ve seen since Macron dissolved the parliament. The difference in this regard between French and American democratic cultures is striking. Here, every candidate is on television seemingly at every hour of the day debating his rivals. The debates are disciplined; the speakers are fluent; they answer the questions they’re asked; they don’t interrupt one another compulsively; they maintain rudimentary decorum. The French have heard from all of the candidates exactly where they stand on all the relevant issues; they have heard the counterarguments; and no one is wondering whether any of the candidates are so demented that their families must keep them on a leash at night lest they wake up and wander into traffic. This makes it all the more dismaying to realize that none of this matters. But French political debates are a sign, at least, that the French still care about their dignity.

Journalists have had difficulty confirming more than one aspect of this account: Who paid for his expensive private schooling? Baffled former classmates tell the media that he never expressed any interest in politics at all. He played Call of Duty a lot, they remember, and he wanted to be a policeman.

This is a stunning piece, Claire, even by your consistently high standards. I found myself repeatedly opening a file where I keep the best quotes I come across.

I believe this one, in particular, is the most profound:

"Politics, in a democracy, is about giving voters what the deep, unacknowledged part of them longs while simultaneously providing them with a political language they can use to justify that choice."

It explains so much of the disconnect between the candidates' rhetoric, the polls, and the eventual election results that has been bothering me since I was old enough to vote!

And every candidate whose natural inclination is to recite statistics and numbered action plans should tattoo this on his left arm:

"Voters may not care about policy, but they care very much how a candidate makes them feel."

I do think you are being a bit unfair here:

"The text is immigration and the cost of living, but the subtext is impulsiveness, resentment, envy, and the sincere desire to be told lies."

Besides a natural resentment on the part of an in-group toward an out-group, there are legitimate concerns about crime, lack of assimilation, job competition, and losing national identity. Candidates who ignore or disparage those concerns certainly don't make the populace *feel* like they're being heard.

I strongly agree that most developed nations desperately need immigrants. Why the candidates cannot explain that simple fact is, also, beyond me. I've long advocated a simple policy (keeping in mind your quote from another essay, "For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong"): "We will accept every person with no criminal background or communicable disease and provide them no public assistance beyond life-and-death situations for a period of X years." (X, in my mind, being around 5 years.) I believe that was American immigration policy from its founding until the decade that started paving the road with good intentions, and it worked very well. (I stand ready to be corrected on both counts :-))

This is great and truly depressing stuff Claire. Looking forward to your take now that it seems the extreme left (not the far right) has won in France