Vladislav Davidzon has for almost a decade been one of the most acute observers of the Ukrainian–Jewish relationship and of the place of Ukrainian Jewry within a developing political nation. His stylish reportage has been invaluable for understanding the dynamics of the Jewish Ukraine in a historical moment. This volume will surely enter the canon as an important document for anyone who wishes to understand this moment.—Wolf Moskovich

A masterful chronicler of the real odyssey of the Ukrainian Jew amidst revolutionary times!—Simon Sebag Montefiore

Claire: Hi! This is Claire Berlinski with the Cosmopolicast. We have Vladislav Davidzon back again to discuss his new book, which I just read, and Vlad—I loved it. I loved it.

Vlad: Oh, wonderful! Thank you.

Claire: I have to say, I was sort of wondering, “Am I really going to enjoy reading this?” Yesterday evening, when I thought I was kind of under pressure to read it quickly and just wasn’t sure I was in the mood for a book about Jews and Ukraine and Ukraine and Jews—I couldn’t put it down. I loved it. It’s so … well, let me back up a little bit. Why don’t you introduce your book, and I’ll add a few comments after you’ve told people what it’s about?

Vlad: Hi, Claire. Thank you so much for having me on again. So. To my neighbor Claire and friend—we live close to each other in Paris, in an undisclosed neighborhood, although I’m sure every intelligence agency that wants to know where it is that we live already has our locations.

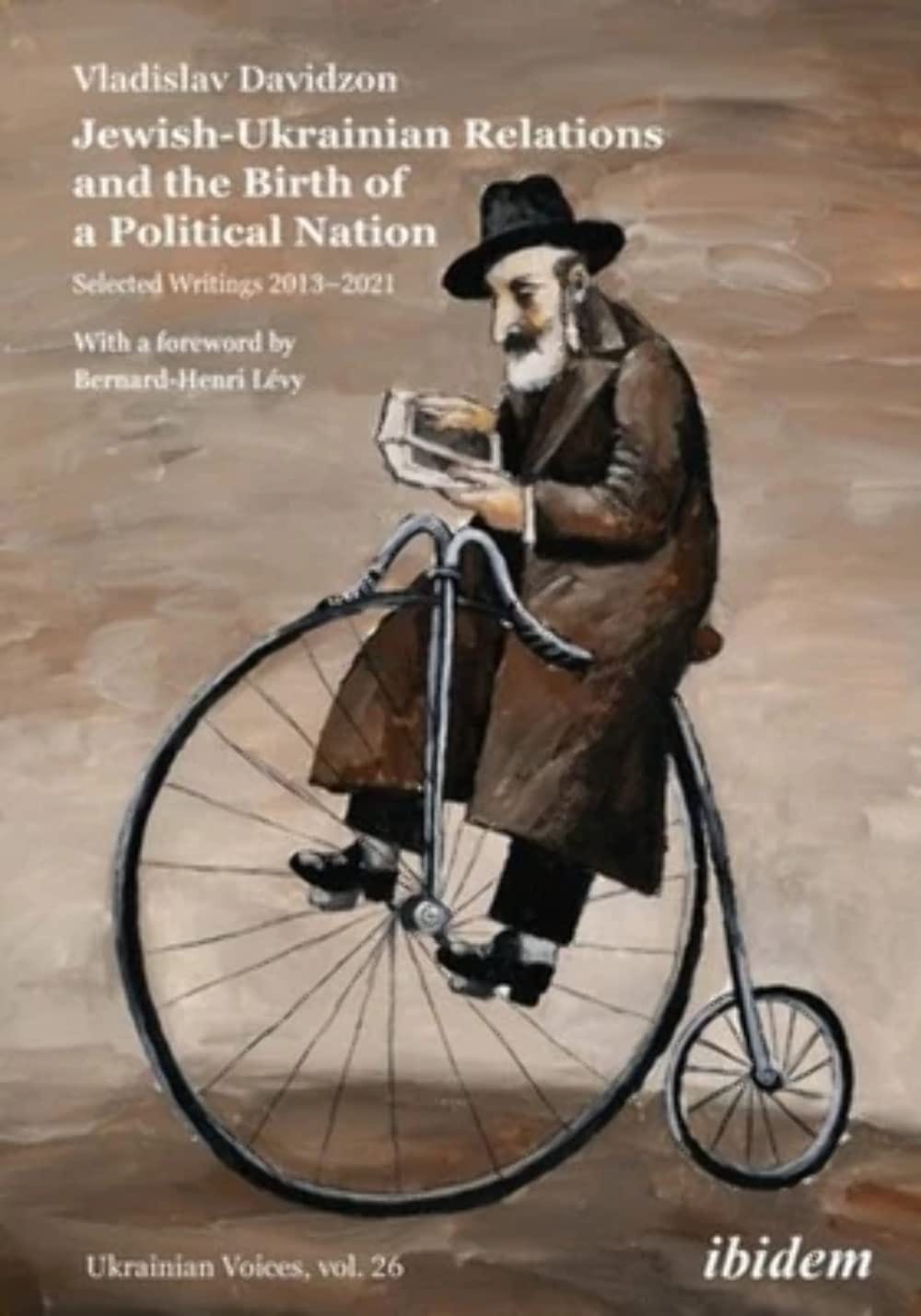

We are celebrating the publication of my second book. It’s called The Birth of a Political Nation. It’s about Jews and Ukrainians. It’s a selection of my best and most interesting pieces on this perennial theme between 2013 and 2023. So, ten years of my best pieces. I selected 20, 22 of my most interesting articles—the ones I think are most useful—and added new stuff, padded them out, and created a narrative.

Claire: Yeah, it all fits together. It fits together as a book.

Vlad: Absolutely, right? You can tell that it does, right? That’s the point.

Claire: I mean, it’s really linked—anyone who’s in any way interested in modern Ukraine, and who, because of the war, has heard a great deal about Ukraine but doesn’t really know what this country is like—this book will—well, I feel like I’ve been there now.

Vlad: No writer could get higher praise.

Claire: Oh, well, they could, actually. I mean the introduction from Bernard-Henri Lévy is pretty good.

Vlad: I love it. I rather love it, but some people might think I’m a bit of a character having read it.

Claire: I'm sorry, I interrupted you. You were telling people about the book.

Vlad: So the book, yes, the book is a collection of my thoughts. It is about …

It is about politics.

It is about memory politics.

It is about trauma.

It is about minority rights.

It is about politics with a big P and politics with a small p.

It is about history.

It is about Russian propaganda.

It is about Putin’s obsessiveness.

It is about the key to understanding this conflict, which is [that there are] two different conceptions of a multicultural, multi-ethnic, multi-confessional Slavic state, post-Soviet.

On the Russian side, you have a markedly totalitarian, authoritarian, centralized autarky that has difference—in terms of particularity—subsumed to an autarkic idea of the state.

On the other side, you have a liberal, democratic, very messy conception of a modern polity, in the middle of Europe, one of, actually the most liberal, in many ways, and one of the most multi-ethnic, certainly in the terraformed-after-Hitler lands of the bloodlands in Eastern Europe, whatever you want to call it, Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands, right?

So you have two different conceptions of how to run a Slavic, post-Soviet state with a lot of different kinds of people living in it. That’s the same with Russia. Russia is also a multi-ethnic, multi-confessional, multi-racial, multicultural, multi-religious state.

And you have two different ideas of how to run it. And you have two different generations of people. One, a Soviet regime—the Putin regime in its sixties. And then you have the liberal, democratic Zelensky political regime, a liberal regime, which is in its forties.

So you have two different ideas and two different generations fighting over what the future of an Eastern European post-Soviet state will be. And the Jews, as people, as an idea, as an apparition, as a figure of speech, and a figure of image—of literature and history and propaganda—are in the middle of this. So you have, you know, even if you’re not interested in Jews, it’s a very interesting book about memory politics.

Claire: Absolutely. The central thesis of the book is that if you understand the story of Ukrainian Jewry over the last decade since the Maidan Revolution, you understand the development of Ukraine as a modern nation-state. And as I was reading it, I thought—

Vlad: —Absolutely. Well said. Thank you. I wish—can I actually have that? I'm sending the last proofs in to the editor today. I can actually get that on the back cover. Would you like that?

Claire: Yes, absolutely. Um—you’re sending the last proofs? Because I found some typos. I wasn’t going to mention them to you.

Vlad: Would you please send them now?

Claire: I didn’t realize. I thought it was too late. Yeah, I’ll send you a complete—

Vlad: —Please send me the typos immediately, Claire. Immediately.

Claire: —I didn’t realize that it wasn’t too late, so I just wasn’t going to tell you.

Vlad: You’re working with a pre-final edit PDF. We’re sending the last edit to—

Claire: But the draft I have is the one you’re working from?

Vlad: The draft you have is—yeah, indeed, it is the one that you’re working on. I mean, I copyedited it, my friends copyedited it. I mean, the people on the podcast don’t care about this.

Claire: —If you order this book today, how long will it take to get to you?

Vlad: The book will be out in a month. I imagine people will get it in six weeks, five or six weeks.

Claire: But they can pre-order it now.

Vlad: Totally, they should pre-order it right now.

Claire: They really should pre-order it. I just wanted to say something about that.

It is not an inexpensive book. It’s US$42.

Vlad: Speaking of which, right before this, since we’re right in the final things, we are lowering the price.

Claire: Really?

Vlad: I think US$31 or US$30, because the people at the Columbia University Press decided that I’m just that cool, that I can sell—

Claire: And I think a book like this—the price is going to be very elastic. A lot more people will buy it if—

Vlad: Yeah, I mean that’s why we’re lowering the price. …. Come, step right up, step right up. We’re lowering the price. One time only. Come to Brooklyn, Brooklyn, Brooklyn. Home of the Dodgers. Home of Vladislav Davidzon. Home of Donald Trump and Frum Trump. Come, step right up, step right up—

Claire: Get your Jews, get your Ukrainians—

Vlad: Get your Jews, get your Jews, get your hot dogs—

Claire: I was just saying, for me, US$30 is still an expensive book. For me, that’s not an impulse purchase. An impulse purchase, for me, is five dollars. That’s how much I think a book should cost. But I’m aware that I’m—that this is completely out of step with with modern book publishing. Nonetheless, I’m going to tell people—

Vlad: —You could steal books, also, Claire. There are people who believe that—

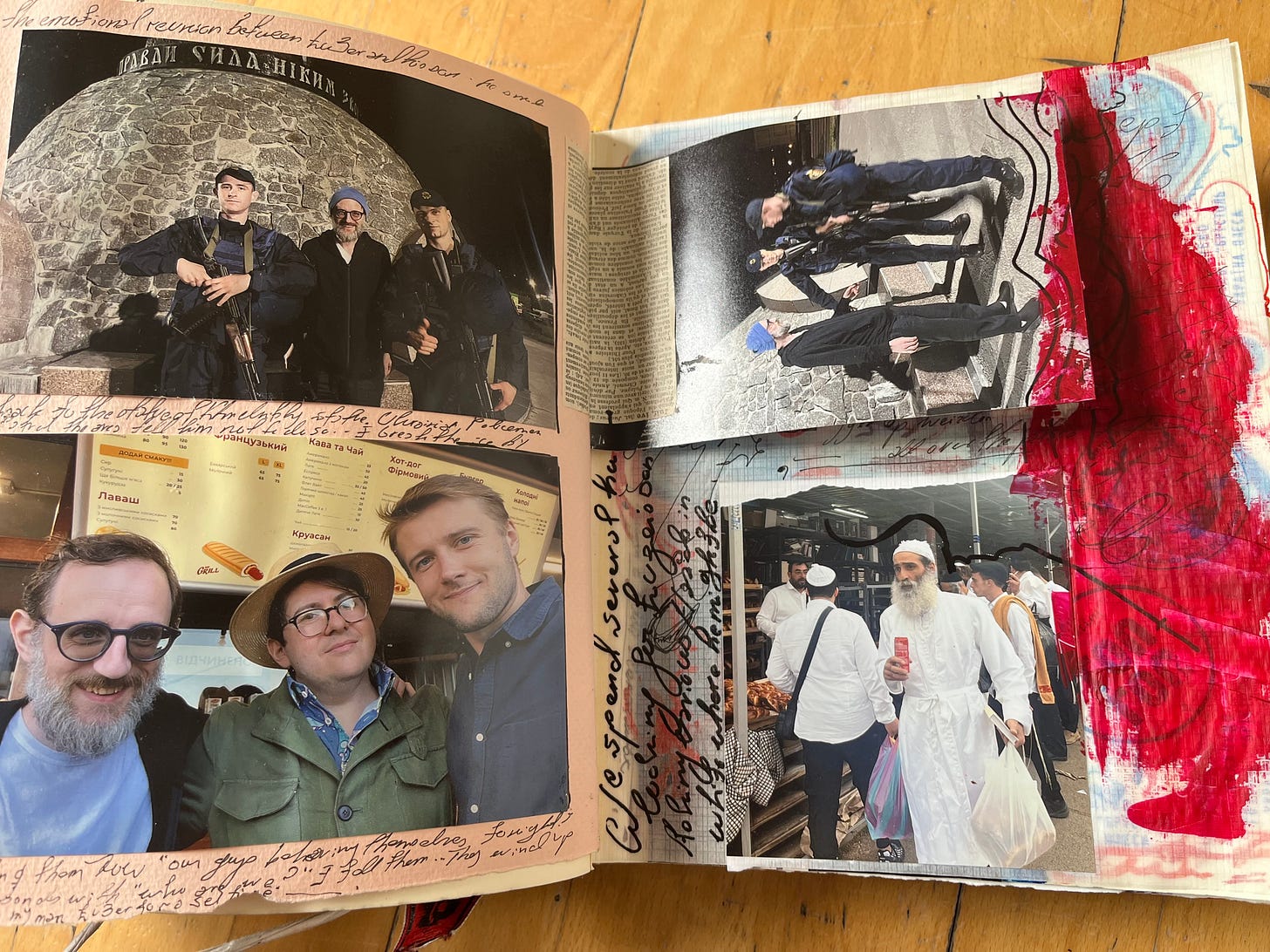

Claire: —Yeah, that’s grotesque. You should buy it because it’s a beautiful book, first. Because it’s got lots Vlad’s artwork in it, and it’s really worth it. I mean, most people will need to be convinced, a little bit. But I really think it’s worth US$30 to read this book. It’s given me a better insight into Ukrainian culture than any other book I’ve read. And I think that’s important, because people outside of Ukraine are connecting to Ukraine as a culture war totem, or an abstract idea. But this brought the people alive, and it brought the culture alive. And perhaps now I think of it, a little bit too much, like Brooklyn. But it really brought a rich, vibrant culture to life.

And to the extent that you can measure the health, the moral health of a society by its treatment of Jews—

Vlad: —and minorities in general. It’s a heuristic for treatment of minorities. Jews are of course the ultimate minority.

Claire: I think Jews are a really good measure because Jews are always the ones who are persecuted first. Right?

Vlad: So, we’re noticeable.

Claire: Yeah.

Vlad: We’re complicated. And we’re economically productive.

Claire: It’s not a huge community of Jews—a quarter of a million, right?

Vlad: Look, here’s the thing, no one really knows the numbers. I mean, some people say as much as a million if you count a lot of people who don’t know that they’re Jewish, who find out that they’re Jewish late in life. There are a lot of people who are halfsies, who are quarters. There are hundreds of thousands of Jews in Ukraine—much less now because of the war, because the population of Ukraine has been emptied out by refugee flows. There are a lot of Jews, now, from Ukraine in Brooklyn and Florida and Israel and Russia, if they were on the other side of the divide—if they were on the other side of the border. It’s like three million Ukrainian refugees into Russia because they were on the other side of the country, that’s where you could fly to. A lot of them in Poland, because there are millions of Ukrainians in Poland and Ukrainian Jews are Ukrainians, after all.

Claire: And the way you describe it, it’s a big, boisterous community. It’s a very Jewish Jewish community with lots of—you know, no one’s hiding it. No one’s ashamed of it.

Vlad: Some people are. And some people for them, it’s not important, including some people who’ve been prime minister recently. No names. The current president, of course, is a Jew and he doesn’t hide it. He’s very elegantly deployed it during the war for the greater good.

And there are a lot of Jews. Unlike Poland. unlike Hungary. Unlike other Eastern and Central European states where the Nazis were more successful in terraforming the landscape. There are a lot of Jews in Ukraine, and it’s a Jewish country, with a large Jewish diaspora still, just like Russia.

Claire: What’s remarkable is that this has occurred in a country that is, for most Jews, synonymous with anti-Semitism.

Vlad: Which is something that I’d really like to change, by the way.

Claire: Well, you can’t change the history. But certainly it sounds as if Ukraine has changed—

Vlad: —I would like, to be very precise, for Ukraine to stop being synonymous with Jew-hatred. That’s something that I’m working on. That’s something that I think of as my mandate. That’s something that is part of my life’s work. I’m not the only one who cares about this, but it’s important to me.

Claire: It’s important. It is important. Gosh, just the other day, I think, we had a reader cancel a subscription because he had lost relatives in Ukraine and found the idea of supporting Ukraine, militarily, intolerable.

Vlad: Please give me his email and phone number. I will personally email him and call him and have a nice conversation with him. He could be Polish. If he’s a Jewish gentleman, I would like to have a personal conversation with him.

I will hunt down and have a personal, intimate conversation with every single Jew in the Ashkenazi, English-speaking, Russian-speaking, Ukrainian, French-speaking world and explain to them why this is important, one by one.

Claire: All right. Well, let’s talk about the book, because there’s lots of points here that I really wanted to talk about with you. First of all, this introduction by BHL [Bernard Henri-Lévy]—it’s just beautiful. He really got you.

Vlad: He likes me.

Claire: He does, he loves you.

BHL is a French intellectual, a very well-known French intellectual who, well—perhaps this will be demoralizing for you to hear, but when he shows up at a conflict, you know someone’s about to be genocided. He’s usually on the [morally] right side of things.

Vlad: He’s great.

Claire: He’s absolutely great in many ways.

Vlad: I love him.

Claire: Except when it comes to cats.

Vlad: Look, it’s okay. Maybe he has an allergy. It’s okay.

Claire: I realized that to read BHL and appreciate him, you have to read him out loud. If you just read him on the page, to the Anglophone ear, he’s unbearably pretentious. But I discovered—because I was reading a book I was supposed to review out loud—that he sounds much better if you read him out loud.

Vlad: It actually is the way it’s meant to be read. Because he’s an orator. He’s an orator and an oracular writer.

Claire: Exactly! Exactly!

Vlad: He’s telling a story in an eighteenth-, nineteenth-century oracular oratory tradition. And it just doesn’t translate perfectly from French, because of the cadences—it just doesn’t translate perfectly from French. And if a lot more people ever read him in French, or read the better parts of his of his oeuvre—which are more poetic parts, less political parts—out loud, they would understand that this is a kind of oracular syncretic storyteller, who’s singing a beautiful song.

Claire: Can I read a little bit of the introduction?

Vlad: Please do.

Claire: It’s just a wonderful introduction. He says, “Vlad came into my life upon my return from Ukraine in 2014.” I’m going to skip a little bit. “... From Paris to Kyiv, from Tangiers to the south of France and New York, I have gotten to know this start-up intellectual, as mischievous as a child and fascinated by rakes, with a devilish laugh and a taunting gaze, arrogant and clever, impulsive but never credulous, ambitious but indecisive, erudite and poetic—” I mean, I don’t think I’ve ever received a love letter nicer than that.

Vlad: I mean, any woman who got a love letter like that has to go to bed with a man who sent it to her.

Claire: “ … Was he a poet or a dilettante, a devil or a dandy? … Was he American or European? Uzbek, Russian, or Ukrainian? Was he bragging when he declared that on the day Russia invaded Ukraine (for he was one of the few people I know who, like me, never doubted that the day would come) he would tear up his Russian passport in front of Putin’s embassy in Paris?”—Well, we know you weren’t bragging because we went together to do that.

Vlad: Thank you yet again, Claire.

Claire: [reading]—“Solid as a rock, brave, funny … ”

Vlad: I’ll take it, I’ll take it!

Claire: Yeah, I want to keep reading from it because it’s just so lovely. Oh! “Here was straight Oscar Wilde—the straight Oscar Wilde—converted overnight into the most curious, intrepid, and acute of war reporters without ever giving up the stylish pouch he wore with the bullet-proof vest, without forgoing his matching jacket and socks, and, above all, without sacrificing anything of his humor and composure.”

He goes on—I don’t want to spend the whole time on this—but he goes on to say that for certain people, a certain historic event brings together all of their talents and all of their insights and—um, how does he put it exactly? Where does he say it? ….

—A historical event that everything within you sensed approaching, an event that once it occurs pulls together the scattered thoughts, brings back dreams from childhood, awakens unused strengths, imparts an aspiration to greatness that prior circumstances had not allowed to emerge. In short, an event that mobilizes and crystallizes the most secret and noble part of the soul.

And he says: The war in Ukraine is your war.

Vlad: And by the way, it’s totally correct, by the way. I went full Lord Byron. I mean, I didn’t even know how crazy and how intense and how amazingly insane I was, and how deeply Slavic I was, and all the ways that my grandfathers and great-grandfathers fought during the wars. Yeah, the war. You really discover who you are at war. I had no idea how focused and intense and just like—I felt no fear. I just, you know, I just moved with total brazenness until I burned out after about six months. But of course, everyone does. That’s why we rotate people out.

Claire: But you just came back from Ukraine.

Vlad: Yeah. Yeah.

Claire: And I think you should tell our listeners about that.

Vlad: Well, you know—I just came back from Odessa and Uman. I was there for Uman.

Claire: Yeah, tell them about Uman.

Vlad: Oh my God, I’m writing an article now about my dear friend Luzer Tversky, who played the Baal Shem Tov, he’s an American actor in a film called Dovbush and we went to Oman for Rosh Hashanah, the eve of Rosh Hashanah, in order to find his long lost sons. He got divorced at the age of 21. He lost custody of the boys and he hadn’t seen them until his late thirties. He wanted to find the 17-year-old son and tell him that he had his blessing before his wedding day.

Claire: Tell our listeners about Uman. I mean, you’ve got a chapter here describing it. You describe it as the Burning Man of Jews.

Vlad: Yeah, yeah. I mean, the Burning Man of Jews is about right. Yeah, it’s just an insane place to be. It’s full of searchers and very religious, very frum people, but also just a lot of hippies—I mean, someone asked me to translate for the cops.

She was this large-bosomed Persian-American girl, with an Israeli passport, who’ was just a hippie or a weirdo of some sort. And I translated for her for the police, because she was arguing with a German camera guy. And in exchange for my help she said, you know, “I have an NGO called ‘Weed the Homeless,’ and in exchange for your help, I’d like to give you this brick of hashish.”

There’s a lot really drugged up people. There’s a lot of people who are high on narcotics.

Claire: Really?

Vlad: Oh yeah.

Claire: So it really is like Burning Man.

Vlad: Oh yeah, yeah. There are a lot of people high on their own supply, which is fantasia and mysticism, and on the atmosphere, but there are a lot of people who are running around are just really high on drugs.

Claire: That kind of surprises me.

Vlad: Why?

Claire: I don’t know. Maybe it shouldn’t. Yeah, it shouldn’t.

Vlad: It’s mysticism. There are a lot of secular Israelis, a lot of Israeli guys, Sephardi guys come, tough guys who like a good party. They’re fairly secular, very traditional. It’s really interesting how this Ashkenazi mysticism, this Hasidic mysticism became kind of an Arab-Jewish-Sephardi thing.

Claire: For those of our listeners who might not know who Nachman was, or why all these people are making this pilgrimage, why don’t you just briefly explain what this is?

Vlad: So the Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism, was a mystic from the Carpathian Mountains in the eighteenth century, early eighteenth century, about 300 years ago, 350 years ago, something like that, maybe 320,1 and he had a great-grandson, one of the many expositors of his values. The mystical expositor of his values was the Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, who codified a very happy version of mystical Judaism, where you worship God not by studying and textual criticism, studying the Torah, but instead dancing and drinking and fornicating and having fun and being close to God through your mysticism. So it was a very peasant form of mysticism.

Claire: Did Jews not dance before that? Because I thought dancing was always part of being a Jew.

Vlad: I think it was always a part of being a Jew, but not like these guys did it. These guys just really made dancing into a theology. I mean, they stripped the theology and they kept the dancing.

Claire: Yeah, so it’s a much more intense, personal, mystical kind of Judaism.

Vlad: Correct.

Claire: And this is kind of the world from which Isaac Bashevis Singer comes, isn’t it?

Vlad: Sure, yeah, and a lot of other people. This is a very mountain Jew, Eastern European phenomenon, which reached its hypothesis in the nineteenth century and then of course was destroyed by Hitler. They were very badly prepared for Hitler. They were wearing black coats, they didn’t have an education, they didn’t know languages outside of Hebrew and Yiddish. Some of them knew Russian and Ukrainian. But the Hasidim were the most open toward—I mean, like open target. Not open, but they were the most openly targeted because they were easiest to get. They were wearing black hats and black coats, and they were not very worldly. They were either eradicated or wound up in Israel, or Antwerp, or the UK—or mostly New York City, New York State.

Claire: Well, some obviously survived in Ukraine. How many actually survived and have been living there continuously?

Vlad: Well, some of them survived and had to give up their religiosity and become Soviet citizens. They couldn't operate as Hasidism throughout Soviet times. There were no black hats in Soviet times, obviously. There was an interregnum, about eighty years, where you couldn’t behave like that. And in that same way, when Uman was forbidden as a place of pilgrimage, during Soviet times, very intrepid and very brave dissident types would go there on Rosh Hashanah. It was a place where in the eighties, I think by the late seventies, certainly by the early eighties, a lot of very intrepid travelers would travel.

Claire: What happens? The Soviet Union collapses, and then do people who have been—

Vlad: It dissolved, Claire. By the way. One of my pet peeves is when people say “collapse.” It dissolved, actually. Relatively painlessly, until now. Unlike Yugoslavia, or the Turkish Empire, or the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Soviet dissolution was actually relatively bloodless. There were regional wars between Georgia and the Armenians and the Azeris, there were wars in the Caucasus.

And there was a war, obviously, between the Chechens and the Russians. But for the most part—other than, clearly, the invasion of Moldova and all that—for the most part, the Russians took fifteen years off before inflicting the pain of the collapse, of losing the Empire, on the rest of us. The invasion of Georgia, the invasion of Ukraine, the Russians—you know, they took fifteen years off in order to deal with their own stuff. Obviously, these are the final earthquakes of the collapse of the Empire. The Empire has been dissolving for thirty years. It didn’t happen overnight. Empires are very big. They live a different lifespan than people do, right? So I don’t like it when people say “collapsed.” It dissolved. At first peacefully, but it turns out, not so peacefully. We thought—and I say this in the introductory article—that we had avoided the bloodletting of Yugoslavia—and the Austro-Hungarian, Turkish Empires—upon its dissolution into national states. That was not the case.

Claire: Explain to me, when the Soviet Empire dissolves, were the Jews in Ukraine—had they been practicing this secretly? Or did they return from Israel, or from abroad, to come back to revive this tradition?

Vlad: Well, so here, so for the most part, they were all secularized. Like, let’s say, 97, 99 percent of them were secularized. Some, obviously, a million and a half, have been killed during the Holocaust. Let’s say another million or so left to Israel and America, including my own family in the eighties and nineties. And then a lot went to Germany. You had a couple of hundred thousand people left, out of a community of several million. Hitler had his solution to the quote-unquote “problem.” Stalin’s solution was to make them good Soviet citizens and destroy their culture. And some of them went to America, from the safety perspective. That was, actually, over the twentieth century, the correct choice. Some of them went to Israel and they became Israelis. That was a Zionist solution. And the ones that stayed had to give up Judaism in order to become Soviet citizens.

Claire: How did they revive this culture? I assume there were no pilgrimages under the Soviet Union?

Vlad: Well, I mean, the rabbis and Israeli Mossad guys that I talked to who started doing it started doing it in the late eighties when the system was collapsing. They started coming in the late eighties. There was a kind of general, let’s say, American—the gold rush for souls, to mix metaphors. In the nineties, there were a lot of people who came, from all religious backgrounds, especially evangelical, to fish for souls in the former Soviet republics. And there was a general religious revival in all fifteen Soviet republics, because religion is part of human nature and part of a normal, ordinary, orderly human society. And people need clerics, and it has a special place in social structure—obviously, you’re not going to get rid of religion. We tried, in the Soviet Union. That experiment failed. And all across the Soviet Union, you had religious revival. Uneven: In some places more than others. In some places, the church or the mosque became captured by the state—let’s say, Azerbaijan or Turkmenistan. Or Russia, for that matter. In some places that process was stalled, because they never went through decommunization: Belarus. In some places it was normal, because people just returned to having a normal country, like the Baltic success stories. In Ukraine, it was a mixed story, because so many people just didn’t come back to religiosity. Most people in Ukraine are still mostly secular, and most Jews are mostly secular. And when the American missionaries came in the nineties, they mostly did their work not in the West, which was deeply Catholic and Greco-Catholic; they did their work in the south and the east, both in the Christian and the Jewish missionary communities. They worked mostly in the Donbas and in the south.

Claire: Was the pilgrimage to Uman invented then? Or had that been a regular occurrence before the Soviets?

Vlad: I think it was a regular occurrence. I don't know about Russian Imperial times. It’s a great question actually. It was something that people did during late Soviet times and during the nineties, it became a big thing. So I’ve been a couple of times.

Claire: So it’s possible that this historic annual pilgrimage is something—sort of a recent invention?

Vlad: In its modern version of 35,000 people and, like, a Jewish discotheque of drugs, yes, certainly that’s very modern.

Claire: So did you feel the religious … did you feel the mysticism?

Vlad: Yeah, yeah, it’s very, it’s always very intense. I mean, it’s very, very, very intense. It’s like a—it’s like a little, very intense version of Bnei Brak in Brooklyn plopped down—Bnei Brak is where the Orthodox live in Jerusalem—plopped down in the middle of Ukraine. It has a very Israeli atmosphere, I would say, despite the fact there’s a lot of Hasidim and Brooklyn Hasidim. It’s just a very Israeli, kind of harried, atmosphere—like the kebab stands are run by Israelis, andrun in Israeli fashion. The businesses are run Israeli-fashion. It’s very—it’s very deeply Israeli, in that sense. Like you know, a secular-religious version of a syncretic-secular-Jewish culture.

Claire: Well, it sounds like things are going better in that regard in Ukraine than they are in Israel, if you’ve seen the news. It’s just awful. Fights broke out on Dizengoff Street in Tel Aviv over Yom Kippur over the segregation of the sexes.

Vlad: Yes, I did notice that. I mean, there’s segregation of the sexes in Uman also, but that’s voluntary. Go ahead—

Claire: —No, go on. I didn’t mean to interrupt.

Vlad: I went to find my friend’s sons with him. He had not seen his sons in two years. I’m writing an article about this now. It’ll come out in Tablet.

Claire: You just got back how many days ago?

Vlad: About three days ago, from Ukraine.

Claire: I want to talk to you about this great interview that you have with Borislav Bereza. Is that how you pronounce it?

Vlad: Bereza, yeah, yeah. My friend who’s now a member—he lost his parliamentary seat in 2019, he was a member of the Ukrainian Parliament 2014 to 2019. He was, like, a straight-up—he was the spokesman for Right Sector. He was a Jewish guy. He was the spokesman for Right Sector. Right Sector is a nationalist, a very nationalist organization.

Claire: Well, when people say that the far-right isn’t very powerful in Ukraine, they’ll say things like, “Look, the Right Sector only got this tiny percentage of the vote.”

Vlad: —And their spokesman was an Orthodox Jew.

Claire: And that’s the part that's mind-blowing. The spokesman is an Orthodox Jew. So these Nazis—I mean, this is the group that makes people say, “Ukraine is full of Nazis”—

Vlad: —I was like, “What about the Nazi stuff?” And he’s like, “Bro.” He’s a tough guy, he served in the Israeli Defense Force, he’s a tough guy. He says, “Bro, what are you talking about? We have ultra right-wing patriots of every race, of every creed, of every color.”

Claire: The interview itself conveys how surreal this is.

Vlad: Yeah, that was from 2014. I think he’s really playing it up to the crowd. But yes, it’s not unrepresentative of that moment, of his moment and him. I have to point out the Right Sector has been somewhat folded into other organizations. It’s declined. Other right-wing patriotic organizations are much more important now. It was run like a McDonald’s, unlike Azov, or something else. It was run like, basically, a chain franchise. And every Right Sector, in every town, was run by different guys. And a lot of those Right Sectors, it was just a local militia, paramilitary, crime groupuscoule that took on the name Right Sector. There was not one Right Sector. And by 2017-18, Right Sectors decline, now it’s not really as important. There’s still people in organizations that call themselves Right Sector, but a lot of them have been dismantled by the Ukrainian intelligence services because they became, basically, foreign bandit structures.

Claire: What I found, among the things that I found interesting about the interview was his defense of Bandera.

Vlad: It’s great, yeah.

Claire: It’s great. I mean, it’s obviously a bit revisionist. But it does suggest how Ukrainians view Bandera. It’s so repellent, from the outside, because we know who he is. But they obviously do not have an accurate historical portrait of him.

Vlad: Well, first of all, yeah—there’s a lot to say on that. Yeah, they don’t know who Bandera was, first of all. Secondly, there’s a lot of Soviet propaganda about Bandera, so when they embrace Bandera, it’s like a “Screw you” to the Russian-Soviet mentality and Soviet narrative. That’s one thing. Another thing is that Bandera is a pet project of certain ideological people, without naming their names, who came to power in 2014 with the Poroshenko administration. And it was really a regional phenomenon that captured, in national memory politics, the country overall. So Bandera is not something that anyone in Chernihiv or Odessa, in the South—Chernihiv is in the north—or certainly in Kharkiv, care about.

He has nothing to do with the history of the Donbas, even very, very, very right-wing Ukrainian nationalists from Donbas cities like Mariupol or Lugansk or Donetsk. They have other heroes that they’re more into. You talk to really, really, really right-wing Ukrainian guys or, you know, whatever, patriotic guys from these—you know, groupuscules or, you know, the guys who fight in the military conflicts—and they don’t care about Bandera. Bandera is very much a Western Ukrainian thing that was hoisted, in terms of memory policy, onto the rest of the country. In a perfect world, that would not be the historical antecedent for resistance that the Ukrainians would look at.

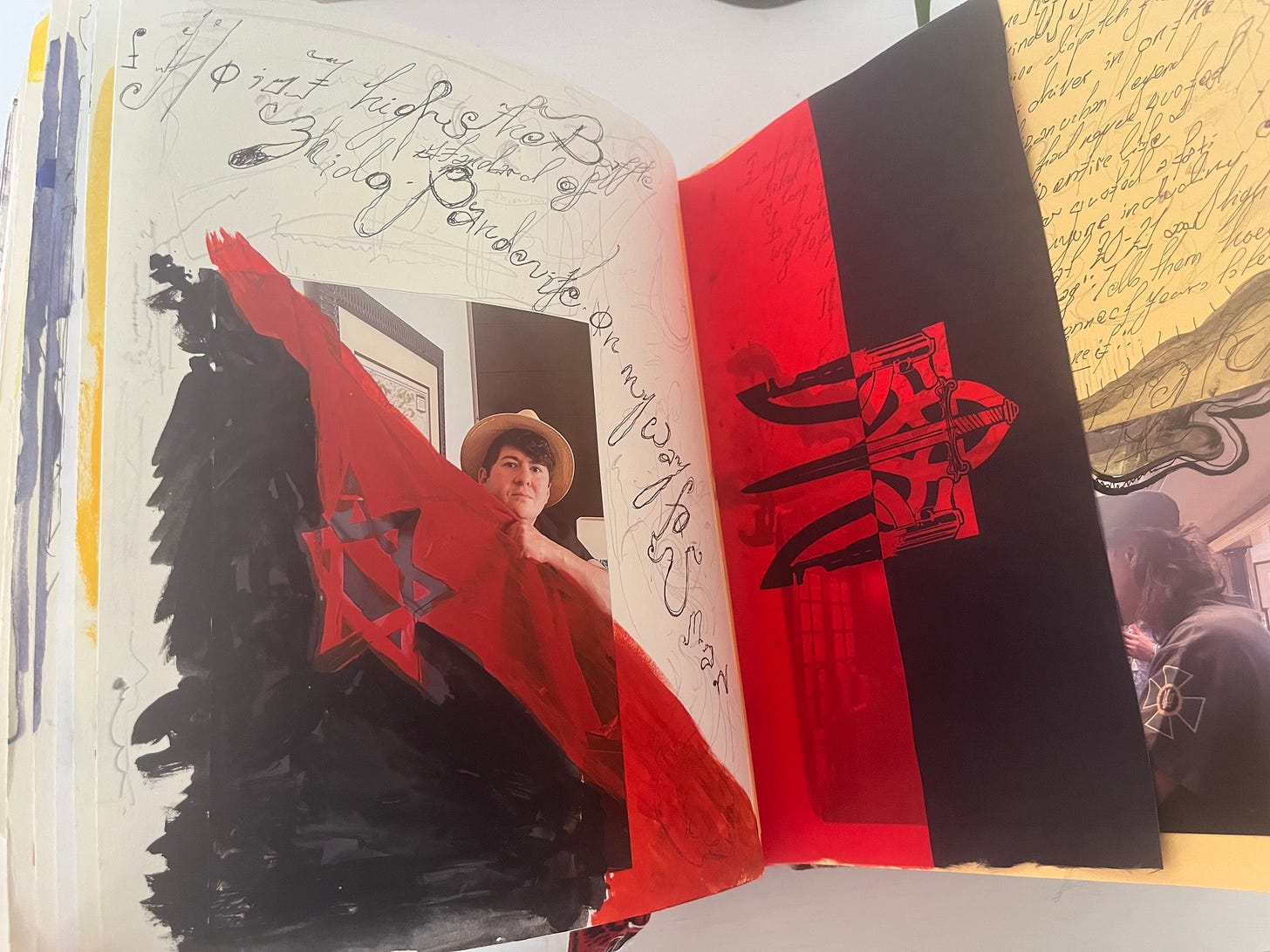

Claire: It’s not doing Ukrainians any favors, because people who want to—

Vlad: Well, here’s the thing. As a Ukrainian Jew, I accept Bandera. It’s Shukhevich and other people who I don’t like. They’re much worse characters.

than Bandera, one. Two, I like the Zhytomyr-Bandera flag. I wore my red-and-black Zhytomyr-Bandera flag with a red-and-black Magen David in Uman and I had—Israelis were like, “What are you doing?” I’m like, “I’m a Zhytomyr-Bandera.” And they’re like, “What the hell? Bandera is good?” I said, “No. I mean, this is post-Bandera. This is appropriation.”

Claire: There’s two Banderas. There’s the historic Bandera and there’s the Bandera who symbolizes something modern, and has nothing to do with the historic Bandera.

Vlad: Correct. I mean, yes.

Claire: But I wouldn’t have known that if I hadn’t read your book.

Vlad: Yeah, that’s right. The valorization of OUN is, as the kids nowadays say, problematic. But also, you know, there’s a war on and I’m not going to tell Ukrainians whose statues to put up. I went to see Zelensky’s first prime minister, without naming his name, a week before the war started. I was doing the rounds in Kyiv, seeing politicians, you know, seeing who’s going to do what during the war. It was already obvious that there was going to be a war. And it was, like, a week before the war started, and I went to see Zelensky’s former prime minister,

a technocratic prime minister. I said, “What do you think about Bandera?”

We had a long conversation. He’s like, “Well, it’s our history.”

I was like, “Yeah. I know. I know.”

And that was—that’s symbolized, for me, the reaction, which was like—shrug—“Well, that’s our history.” And I said, “We respect that. Yeah, I respect that as a Ukrainian Jew.” Ukrainian Jews mostly don’t care. It’s outsider Jews who care.

It’s Russian Jews who make an issue of it, and it’s Poles for whom it’s a real problem, you know?

Claire: Yeah.

Vlad: Look, I have a friend who is a hipster, he’s an Odessa-born conceptual artist, he’s a hipster, he lives in Berlin, he makes conceptual art, he’s my friend, and he once made a jocular—it was very hilarious—Bandera-themed musical, and the theme song of the song, written by my friend, a Jew from Odessa, a conceptual artist, was, “Was he a villain or was he a hero?”

Claire: I just want to read one little bit of this interview before moving on to the next chapter. You ask him, you say to the Right Sector spokesman, “The Right Sector is also often accused of being quite reactionary on the question of LGBT rights, gay rights. What’s your relationship personally and also as a party toward gays?” And he says:

The infringement of LGBT rights is, much like anti-Semitism, a real and substantive problem. But I don’t know of a single country where homophobia doesn’t exist. I do not know of a country where there are no homophobes or xenophobes. Such people exist everywhere. Personally, I have no issues with LGBT and think this is a matter of personal freedom. … Yet even more than that, I, personally, want to go on the record as saying that I love the work of Freddie Mercury.

Vlad: Yeah, he’s a deeply parodical character. He’s got a left earring, and he’s got a cool jacket on. He’s like, “I love the gays. Right Sector, we love the gays.”

Claire: You tell him, “You come off as an honest guy and I believe you.” Did you believe everything he said?

Vlad: In the moment, I don’t know what to think.

Claire: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Vlad: I now know better. Anyway, he was reprimanded by the Central Committee of Right Sector right after this interview for unsanctioned statements about the gays. And then he was like—he was saying that about Freddie Mercury. Right Sector’s Central Committee and Politburo does not favor these comments in favor of Freddie Mercury.

Claire: Alright, so the next chapter—I really admire the way you do this, it flows pretty naturally because you introduce Sheptytsky, is that how you pronounce it?

Vlad: Yeah, Sheptytsky. Teah. And I write a lot about Sheptytsky in the book, yeah.

Claire: Yeah, and it seems like you did a lot of archival research? Is this all your own research or are you drawing on the work of other scholars? You don’t have to answer that.

Vlad: Look, I did talk to scholars. In fact, one very pedantic scholar accused me of, “This is such primitive reductionist garbage … ” And I was like, “Welcome to journalism, brother.” I read everything that there was. A scholarly history in English, some in Ukrainian. I don’t read Polish very well, so I talked to sources who were au courant of the Polish scholarship.

Claire: Yeah, yes. I just wanted to mention this—skipping around a little bit, but just before I forget it, there’s the incredible fact that on invading Crimea, Putin announced proudly, “The Jews there can now celebrate Rosh Hashanah again.”

Vlad: He’s like, “We’re doing it for the Jews. Now our brothers, the Jews, can celebrate Passover.” It was great.

Claire: They’re looking at each other and saying, “We do this every year.”

Vlad: They do this every year. And what was funny was that the Chabad rabbis, it’s split Chabad down the middle, because the Chabad rabbis, they’re cousins, brothers, and brothers-in-law, and they’re all married to each other. And you literally had a split between the Russian and Ukrainian Chabad. I don’t write about this in the book. It’s fascinating. And the rabbi in this aforementioned synagogue in Sevastopol was literally like the cousin of the rabbi in Kharkiv and the second cousin of a rabbi in Odessa by marriage. And they all had to put out competing statements in order to make the secular authorities in their new country happy. Which is always the case with Jews, you know?

Claire: Did you see the, what is his status, the chief rabbi in Ukraine? He put out a Frank Sinatra—him, singing Frank Sinatra, for Yom Kippur—

Vlad: Which one? Do you mean Dov Bleich?

Claire: The one with the big bushy beard.

Vlad: Oh yes, he’s very nice also. He’s a star now. I guess he wasn’t expecting that.

So there are a couple of chief rabbis. We’re talking about Moshe Asman, Giuliani’s great friend.

Claire: Hold on a second. I’ll find it for you. It’s Moshe Asman, yes.

Vlad: It must be Moshe Asman. He’s a star.

Claire: Do you know him?

Vlad: I know all the rabbis. Yes, I know Moshe. I know Rabbi Asman, yes. Rabbi Asman is a real fighter. Moshe Asman, yeah. Rabbi Osman became a star in Ukrainian social media for his, like very over the top—

[Sound of singing rabbi ... ]

Claire: It’s great isn’t it?

Vlad: Yeah, it’s funny because all the chief rabbis of Ukraine were either born in St. Petersburg or served in the Israeli Defense Forces. It’s all very funny. He’s become a media celebrity all over Ukraine for his over-the-top patriotism. Literally like a shotgun in one hand and a Torah in the other one. No Pasaran! They will not kill us! They will not take us to the nether regions! They will not pass!

Claire: Yeah, and God bless him. It’s so astonishing that Putin has managed to convince the number of Americans he’s convinced that he’s fighting Nazis.

Vlad: Yeah, what’s astonishing about that?

Claire: What’s astonishing is how effective the propaganda is. And how weak we’ve been in the face of it.

Vlad: Well take a step forward. You literally have a kind of, a new version of fascism. It’s very complicated. I’m not one of these people that refers to the ruzzists, the fascists, to Russian fascism. It is a postmodern regime with a new version of fascism. It’s not a complete Hitlerite-style regime in terms of political economy of the country. It doesn’t have total control, the regime, in the way that Hitler did. It’s not totally—

Claire: I’m not fond of using the word fascism to describe these—

Vlad: —I’m not either. It’s fascism-light, or whatever.

Claire: Fascism is a particular movement, in a particular period of time, that only made sense as a contraposition to Bolshevism.

Vlad: That’s right. There’s no more Bolshevism. And this regime does not have a—

Claire: —It doesn’t have a fascist theory.

Vlad: It doesn’t have a mystical, essentialist, vitalist component to it. Doesn’t have a theory. It’s a mishmash.

Claire: It’s a tyranny. We have a good, old-fashioned word for that.

Vlad: It is a tyranny. Both forward-looking and backward-looking at the same time. It's very interesting. The reason I’m saying this: I don’t like the misusage of the word fascism. I don’t like it in America. I don’t like it in Eastern Europe. But it is kind of fascism. We do have a kind of fashy country, a dictatorial regime which is committing basically genocide against its neighbor in order to denazify a country run by Jews, basically. Yeah, I mean Ukraine, yeah.

Claire: But did you see—was it yesterday?

Vlad: I mean, I say, run by Jews, in a funny way. But like the president, his chief of staff, and the defense minister upon the invasion were Jews. And when he got rid of the Jewish defense minister, he put in a Crimean Tatar Muslim defense minister. That’s not a Nazi regime, obviously. And you do have a kind of Nazi regime, a light-fashy regime trying to denazify aa country led by a secular Ukrainian Jew.

Claire: It’s so distressing that Putin’s—that Russian propaganda has been as successful as it has been.e—

Vlad: That's how propaganda works. It’s successful. No?

Claire: You would think that—when you have a climate of freedom of expression, the truth is supposed to rise up and defeat the lies. But it doesn’t seem to be. Rand Paul, yesterday or the day before, was standing up and going on about how Ukraine was corrupt—and, I mean, it is corrupt, but he was suggesting that Ukraine’s corruption and its repression of Christians and its—

Vlad: Well, he’s an opportunist. I mean, he and the people who make those arguments are opportunists.

Claire: Well, he’s an opportunist along very particular lines. He just echoes Moscow’s line.

Vlad: Yeah, that’s right.

Claire: Cathy Young replied that this was objectionable in some way. I don’t remember the exact words. And the number of people who jumped in to echo what Rand Paul had said—very certain of it—they’re just certain that Ukraine is full of Nazis, profoundly—no better than Russia, certainly. No different from Russia. This is just some sort of conflict between one authoritarian thug and another. How can so many Americans believe something that is so abjectly stupid?

Vlad: Because the legacy media has collapsed.

Claire: No, the legacy media is not promoting this.

Vlad: Well, look, you really want to get into media? No, the legacy media has collapsed. Because, after a couple of years of Russiagate, another stupidity, and the general collapse of the standards of the legacy media, no one trusts the legacy media. I mean, the media has only like 25 or 28 percent of American people who say that they respect it or trust it. It’s the least trusted institution in American life. So people have retreated into their own little epistemic bubbles, and Ukraine has become a heuristic for other sorts of culture war. And it’s cost-free. Everything that you, as a Republican or as a Conservative, might attack within America, there are costs and benefits within internal American culture war stuff. Ukraine is far away, most people have never been there. It’s cost-free, you can just bloviate about it and no one cares, right?

Claire: We’re also in the age of instant communications on social media. You would think that people who are in doubt about this would just speak to a Ukrainian.

Vlad: They’re not in doubt, they just don’t care, Claire. It’s different.

Claire: You don’t sound as angry about this as you should be.

Vlad: It’s funny that the Ukrainian nationalist is explaining to you why … the Ukrainian patriot is explaining to you why he’s not … I think some of those people are deceived—

Claire: The military aid is being held up, and might in fact stop completely if Trump is elected, because of this crap.

Vlad: Yeah, it’s true. I mean, it doesn’t make me happy. I mean, I’m fighting against it. But, like, I understand the deep roots of it and the deep roots of it are partly the failure of American elites to tend to their own garden and keep up the credibility of their own institutions. And, you know, Ukrainians become a political football, especially with the Trumpets base.

Claire: I don’t buy that this is the elite’s fault. It is the moral responsibility of people who refuse to inform themselves and get their news from enemy propaganda.

Vlad: People are idiots. People are idiots. I don’t believe that the public has more responsibility or like even—

Claire: You mean they’re like dumb oxen?

Vlad: Yeah, I’m kind of a misanthrope. I’m an Eastern European misanthrope. I don’t—I believe that, you know, like, the people who are spreading the propaganda, who should know better—everyone’s—the people who don’t understand Russia-gate or Ukraine-gate—those things are hard to understand.

You have to have a lot of insider information and a good sense. And people have a lot to do. They have kids, they have busy lives. They rely on experts like me to explain things to them. And some of those experts failed, and some of those experts were in the media that spread Russia-gate.

Claire: One thing that I was thinking reading this thought is, “It’s just going to go completely over the heads of the people who most need to read it. It’s just—it’s literate. It’s … they’re not going to read a book like this.

Vlad: Look, if I sell 10,000 copies of an academic book about important things, about choosing Ukrainians, I’ll be happy. I didn’t get into this business—I would have gone into banking, like my father demanded, if I wanted popular success, you know?

Claire: Yeah, but you just said, “It’s for me to explain these things to them.” So how are you going to explain it?

Vlad: You found the contradiction, yes. The contradiction is internal. I believe the provenance of God and Claire Berlinski will get us through the long dark night.

Claire: I wish we had a president who was capable of using the bully pulpit to explain this.

Vlad: Well, the president is playing a double game because he doesn’t want the Ukrainians to win. That’s the thing. He doesn’t care. I mean, he... I know so much. I know so much.

Claire: Tell me what you know.

Vlad: Some of it’s off the record.

Claire Well, can you give, like, hints?

Vlad: So, in a particular way, the failure of the Biden administration is the failure of Biden himself. Because he was the Obama Administration’s point man in Ukraine, in 2014 to 2016, until the Trump Administration came in. And it was his portfolio. Obama gave it to him. And since the Obama Administration did not want the Ukrainians to fight back. They said, “There’s no possible world in which we care about Ukraine more than the Russians do”—they kind of always, from the very beginning, tied the hands of the Ukrainians and how they could respond. So the Ukrainians muddled through and the Russians didn’t use enough force because they weren’t willing to go all-in.

I mean, in order to achieve his policy objectives, Putin really should have invaded in this way in 2014. He would have taken the country. There was no army. He should have done that nine years ago, eight years ago, seven years ago. It’s too late. The Ukrainians had the chance to build state capacity and a very serious military apparatus, as people have noticed. Not nearly as serious as the Russian one, but, you know, serious enough to give a good fight.

Claire: Well, without a navy, they’ve taken out the Black Sea Fleet!

Vlad: They had a navy in 2014. Some of it defected and some of it was blown up by the Russians, sunk by the Russians. They don’t have a navy now, they did in 2014.

The Biden Administration is in some ways doing a good job, in other ways it did not prepare the Ukrainians for the war, and it’s prolonged this war by a lot, by slow-rolling it. So I’m not one of these guys who thinks Biden’s doing good. I mean, I’ll defend him to Republican conservatives because—

Claire: We agree about this, but you suggested that you had some insight into Biden’s thinking. What happened to the Biden who was so outraged by what he saw in Ukraine that he said, in Poland, “This man cannot remain in power,” and his aides had to walk it back?

Vlad: Yeah, that was a great moment. I was there. I was there when he said it.

Yeah, I wish that we still had that guy now. But the National Security Council around him is just too timid, and they are too afraid of the Russians and escalation, nuclear war, escalation in the Black Sea. You know, they’re just not ready to go full in. So they’ve made certain decisions that they want to slow roll this. They don’t want the Russians to win, but neither do they want them to lose too badly.

Claire: That’s insane. It’s insane. It’s just the wrong posture, strategically. And what drives me crazy is that there’s no alternative. This is where a normal Republican Party should be making this criticism, and should be trustworthy with national security, and instead they’re a complete catastrophe and a disaster.

Vlad: Yeah.

Claire: I mean, I’m not saying that the fear of nuclear war is an insane fear. Of course I think it’s a very real thing to be afraid of. But the idea—you know, you either trust in deterrence or you don’t. I mean, going halfway is the worst strategy. Well, not the worst strategy. It’s the second-worst strategy. And I just don’t see that … you know, I think Trump will withdraw from NATO in his first day in power if he’s reelected. And I just don’t see Americans having a conversation about how serious this situation is and what this would mean for the security of the entire world.

Vlad: Yeah.

Claire: I don’t know what to do beyond what I say and what I do to get people to take it seriously.

Vlad: I don’t know. I really don’t know. I mean, will people read my book? Will it change any minds? If I change the minds of fifty people, if there are fifty good men? Should we level the city? I don’t know. Do you think fifty people will read my book and change their minds? Fifty, probably. Five hundred, yes. Five thousand, possibly.

Claire: The book certainly changed my views and explained a lot to me.

Vlad: Well, good, so okay, so let’s keep going, right? Do you believe in the power of a text? Do you believe in the power of a text, Claire?

Claire: Absolutely, I do.

Vlad: Very Jewish of you.

Claire: Tell people about Andrey Sheptytsky.

Vlad: Andrey Sheptytsky was this very heroic and remarkable man. He was a giant, a gentle, beautiful giant. He was like a six-foot-nine Polish-Ukrainian aristocrat. He was the head of a Greco-Catholic Church during the war and he saved a lot of Jews. And he was pivotal for Jewish-Ukrainian relations. His brother Clement did a lot, also.

Because of politics he was never named Righteous Amongst the Nations by Yad Vashem, which is of course a great oversight. It seems they very deliberately decided no not righteous enough.

Claire: Its seems like more than an oversight. It seems they deliberately decided, “No, not righteous enough.”

Vlad: There’s a lot of politics there. I mean, the book gets into the politics. I wholeheartedly agree with the campaign to make them righteous amongst the nations. This is a good thing and we should do it and that would be one way of paying back debts. And there are a lot of very important and smart and influential people who work on that campaign. and I'd like to count myself amongst those people. But, you know, a lot of the people who ran Yad Vashem were Soviet Jews from the Russian side. The previous gentleman—

Claire: —Oh, Vlad. Page 80. You’ve got a big whopper here. “If Zelensky actually does become president of Ukraine?”

Vlad: Well, I mean, this is a reprint. Right. In what context did I say this? Yeah, I didn’t notice that.

Claire: You’re talking about Poroshenko and you say he’s not the only candidate playing the Jewish card. “Zelensky, the current frontrunner, is a 41-year-old Jewish comedian and actor whose primary suitability for the job is his experience having played a schoolteacher.”

Vlad: Well, I mean, it says at the end of the book—at the end of that essay—it was reprinted from 2018. I should put that at the front.

Claire: Yeah, you should put it in the front. You should put it in the front.

Vlad: Page 81, you say? My book is being edited in real time. Thank you so much, Claire.

Claire: You’re so welcome. You’re so welcome. One other thing before you go, you made an observation which I think is really important, which I'd never thought about, saying that the Holodomor should be understood as a Jewish catastrophe as well as Ukrainian, and I had never thought about that. I had never thought that that’s our history too.

Vlad: So the Holodomor, of course, killed hundreds of thousands of Jews who were Ukrainians also. They were also in the countryside. You know, if you can’t get bread, you can’t get bread, doesn’t matter which religion or what color your eyes are. There were hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian Jews who starved to death during the Holodomor because of the fact that they were Ukrainian peasants, rather than Jews, first and foremost.

Claire: I wonder why that’s not more a part of Jewish memory. Is it because what happened subsequently just blotted out all other memory or is it because no one survived it to tell the story to their kids?

Vlad: No, a lot of people survived it. The Jews who were in the countryside starved. The people who were in the cities didn’t have—I mean, the people went from the countryside went into the cities looking for food and they were more likely to survive in the cities. It’s in the countryside that people starved to death, right? Although, I mean, some people died in the cities also. But it did purge the countryside of the people who were living there. And so the Jews in the countryside were the ones that starved along with their Ukrainian farmer—peasant, whatever—neighbors. And a lot of it—

Claire: By definition, if you starve, you do not emigrate, you do not pass the memory of this down to your kids and your grandkids.

Vlad: Yeah, but a lot of people who starved just ran away to the nearest city and found food there. Not everyone who’s starving died, some people survived. I mean, like millions of people died during the starvation, It was terrible. It was a Ukrainian catastrophe, but starvation does not target people based on religion or culture.

Claire: How many Jews perished in the Holodomor?

Vlad: I imagine it’s 100,000? It’s a question I’ve never seen interrogated. But you’ve got to remember that the large-scale starvation and the entire population of Ukraine watching people eating their children, eating their dog, dying in is streets with bloated bellies—the trauma of that, and the trauma of the communists going around killing peasants and taking away their land, it led to the preamble of what happens six years later. You have to understand that the Holodomor led to the trauma that partly allows the Holocaust to take place. I’m not saying that is the cause, clearly not, I’m not some sort of revisionist—

Claire: It led to devaluation of life and the toleration of obscenity

Vlad: Well, I mean, like, it’s just—you’re living in a psychotic place. You’re living in a crazy place where people are dying, in a place where communists are running out of guns, where you just survived a brutal war and civil war ten years ago, nineteen years ago, your parents survived a brutal war. And then ten years ago, seven years ago, six-and-a-half years ago, people were starving to death. And now there’s an occupation and another war, and people are dying again—well, it

contributes to an atmosphere of death. Of devastation, of destruction, of trauma.

You know, it’s a cascade effect, that’s what I’m saying.

I’m no way—please do not, anyone, call and accuse me of saying that the Holodomor led to the Holocaust in any way. What I’m saying, I think, and I’m trying to say it very precisely to not cause any historiological or revisionist issues, is that the suffering of the Holodomor created the atmosphere of trauma and, you know, being able to ignore trauma as a survival mechanism, that led to the capacity of the Nazis to kill people. Obviously, not the only reason. Clearly, it’s a multi-vector, multi-origin story, but it’s an underplayed aspect of a story that you don’t hear spoken about very often, which it should be.

Claire: And as you point out later in the book, when you’re looking at contemporary Eastern Europe, especially when you’re looking at the emergence of far-right groups across the region, it has roots in the absence of a proper mourning of what has transpired in the past century.

Vlad: Yeah, yeah, absolutely, yeah. I mean, like the OUN. Even the OUN was a response to the loss of democratic self-governance. The Polish and the Ukrainians in the borderlands, Poland-Ukraine, started killing each other, whereas they lived harmoniously, more or less, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire and they had devolved educational rights and cultural linguistic rights. Yeah? So a lot of the Polish-nationalist stuff and Ukrainian-nationalist stuff—with the Jews in between, of course, always, without guns—was an outcome of, you know, the destruction of democratic norms. I’m not saying the Austro-Hungarian empire was the most democratic place. It was sometimes very liberal. Especially in the outposts, like in Chernowitz, where my family was from, where Jews, Ukrainians, and Poles live together in some sort of productive, harmonious way until World War I, until the Bolshevik War, until the Communists, then the Nazis, the Polish Partition, all this. The Jews fall victims to various very nasty, very nasty things that happened because of—not them. I think that’s one way of putting it. Like the pogroms, the 1905 pogroms were peasant pogroms, but they were also—this was an effusion of unhappiness with the Tsarist state, right? These are the urban riots that the Tsarist regime was so petrified of. They didn’t want pogroms against the Jews. It was an effusion of the same kind of peasant rioting that would bring down the regime. Right? So UPA and the Volhynia massacres, this is an outcome of, you know, basic tribal warfare, right? I mean, I’m not apologizing for any of this. I’m trying to—

Claire: No, I’ll just read right from the book. You write,

Arguments over who has suffered the most ultimately debase everyone involved. The extension of mutual empathy need not exclude anyone. The Jewish diaspora in Israel can do more to acknowledge the local particular history without undermining the unique horror of the Holocaust, just as Eastern Europeans need to be responsible and sensitive to historical realities as they craft post-Soviet national identities. But all that will require overcoming contemporary geopolitical realities on top of the already heavy burden of history.

This is the thing. This war. The blood had barely dried when this war broke out.

No one is getting any chance to come to terms in any way with any of these horrors.

Vlad: Yeah, that’s right. That’s absolutely right. Yeah.

Claire: All right. On that note, let’s draw this to a close because—

Vlad: Yeah. Yeah, thank you so much, Claire. I’m very grateful. There’s a lot to say.

Claire: There is.

Vlad: This book is a culmination of ten years of my work. I’m trying to—you know, having returned to the land of my ancestors, I’m a repatriate, of course. I’m a repat. This is where my ancestors are from. This is where my wife’s from. This is where my people are from. I have a deep identification with the Ukrainians and the Jews. These are my people. I’ve been criticized, by some Jews, for being too soft, but I don’t think so.

I’m very empathetic to the understanding of the fact that what happened during World War II took place without the Ukrainians having their own states, you know, like the Germans had a German state, what they did was under the auspices of a German state. Neither the Poles nor the Ukrainians can be held to the same level of responsibility as can the French or the German populations who are governed by Frenchmen and Germans, right? Whatever happened during World War II, it happened under the auspices of occupation, and so the Ukrainian political nation, just like the Polish political nation, I—as a Jew—do not feel has the same level of responsibility as—

Claire: When you compare levels of responsibility with Hitler, it doesn’t suggest that there’s—there’s plenty of evil to go before you’re at Hitler's level of responsibility.

Vlad: Yeah, but they did have their own state, is the point. And I’m very empathetic to that argument. Obviously, you couldn’t have those arguments, those historical arguments, before 2014. And the Ukrainian state went very far in having a very long-sided conversation, dialogue, within the country about all this, right? Not as much as it could have and also at the same time they were celebrating people like the Canadian gentleman, the Waffen-SS guy who stood up for the parliament.

Claire: That was a screw-up.

Vlad: That was a screw-up. That was a terrible, terrible screw-up.

Claire: What does it say about Canada that no one present thought, “If he was fighting the Soviets, that means he was not a good guy?”

Vlad: Yeah, it’s kind of weird that they didn’t—that they don’t know the history. I I don’t know Canadians, but it’s obvious to me if he was fighting the Soviets he was on the bad side of things. I mean, obviously, a lot of Ukrainians were fighting the Soviets because they wanted their own country. They were fighting—

Claire: You know, our listeners might not know what we’re talking about

Vlad: Claire, explain please.

Claire: I don't remember his name, but when Zelensky was in Canada, they honored someone who was portrayed as a Ukrainian war hero, and—

Vlad: This gentleman’s name was Yaroslav Hunka, a 98-year-old Ukrainian-Canadian who fought in the Waffen-SS. He was a veteran of the Waffen-SS and it was like the Galicia 1 division. The division was put together after a lot of the Holocaust, and historians say that the Galicia 1 Division didn’t actually, as a unit, do anything against the Jews. Obviously, a lot of the auxiliary policemen and soldiers and volunteers who joined up did kill Jews and did kill Poles. I mean, it’s an entire mess.

Claire: Well the main thing is that you don’t honor a member of the Waffen-SS in the Canadian Parliament. But no one figured out that that’s what he was, because they just didn’t put two and two together.

Vlad: Yeah, it’s like, you know, how do you not understand that a Canadian who fought against the Russians was fighting in the woods against the partisans, you know?

Claire: It’s the kind of historic illiteracy that—do you remember when Reagan went to Bitburg?

Vlad: I don’t because—

Claire: —right. For some reason, he was scheduled to go and lay a wreath at Bitburg. Where all these Waffen SS were buried. And there was a huge controversy about it when people realized this is not a good place for the American president to be going. But there was also this real worry that if he pulled out at the last minute, it would be very offensive. And no one was quite sure what protocol demanded.

My grandfather had the solution to the problem. He was very proud of it. He said he should go. He should put down the wreath. Then he should unzip his trousers and piss on the grave.

Vlad: That’s a … that’s a position.

Claire : All right, I’m going to let you go.

Vlad: Thank you so much. Thank you so much for this great talk. It was really, really nice to talk to you about it.

Claire: Everyone go out and buy this book.

Vlad: It’s trending on Amazon.com.

Claire—He was born in 1698 and died in 1760.

Share this post