No Confidence. No Exit

Macron says he's not going anywhere. Neither is the French parliament.

If you’re a new subscriber to the Cosmopolitan Globalist, I recommend these articles as the background to this week’s news from France:

Hunger Games: Fifth Republic. How the French political system works.

Dramatis personae: A field guide to the French far-right.

Dramatis Personae: A field guide to the French far-left.

The story of the snap parliamentary elections in June.

I also discuss these elections and their significance in The Flight from Reality.

Those of you who remember this saga from the articles above will recall the following: Last June, Emmanuel Macron’s list was thrashed in elections to the European Parliament. Marine Le Pen’s National Rally, meanwhile, made significant gains. To France’s shock, Macron responded by calling snap legislative elections. He did not need to do so. The decision was incomprehensible. It threw France into a state of complete hysteria.

Legislative elections, in France, are conducted in two stages. In the first round, candidates from the National Rally (the renamed National Front) and a far-right splinter faction of the otherwise center-right Republicans took 33 percent of the vote. A coalition of left-wing parties, terming itself the Popular Front, took 28 percent. The largest party in this coalition was Ungovernable France, led by far-left lunatic Jean-Luc Mélenchon.1 Macron’s own alliance of centrist parties, called Together, took a pitiful 21 percent. France was trapped, therefore, between the unacceptable and the unthinkable.

A record number of constituencies, 306, went to three-way runoffs, with five going to four-way runoffs. The prospect of a government led by the National Rally was anathema to the other 67 percent of the electorate, so as usual, candidates from the left and center made tactical alliances, withdrawing candidates from seats where their competition could hand the National Rally an absolute majority.

On the eve of the second round, on July 7, I wrote that the results of the first round meant that France had committed itself to one of three paths: far-right, far-left, or chaos. Given the insanity of France’s far-right and far-left, it was to my great relief that France chose chaos. The second round resulted in a hung parliament. Thanks to the backroom deals made to deny the far-right an outright victory, the far-right was, indeed, denied an outright victory. The Popular Front’s candidates took 180 seats in the 577-seat National Assembly. Macron’s Ensemble coalition took 159. Candidates backed by the National Rally took 142, and center-right Republican candidates won 39. No party attained the 289 seats required for a majority.

Theoretically, the French president may appoint anyone he pleases as prime minister. But traditionally, because parliament retains the prerogative of passing a motion of no confidence, the president nominates someone from the political bloc with a majority. When no one has a majority—the situation that now obtains—the government hangs by a thread. The usual remedy for this would be to call an election, but Macron can’t do that: You are only allowed to do it once a year, and Macron wasted his chance.

Macron refused to appoint a far-left or a far-right prime minister. After a period of haggling that resulted in France having no government for the longest period in modern history (no one missed it), he at last gave the job to a respected and venerable center-right technocrat, Michel Barnier. Barnier, who led the Brexit negotiations, enjoyed a reputation as a particularly experienced and skillful negotiator. But nothing could have prepared him for negotiating with the French.

The far-right was profoundly embittered, believing that its lead in the first round entitled it to govern. Predictably, it accused the center and the left of maneuvering, undemocratically, to deny the people’s will. Mélenchon, meanwhile, believed that because the Popular Front had taken the most seats in parliament, he should be allowed to govern; when Macron refused to appoint him prime minister, he likewise accused the center and the right of maneuvering, undemocratically, to deny the people’s will. (He accused the rest of the left of this, too. Infighting among the Popular Front broke out before the final ballot was cast.)

The tripolarization of the electorate produced unprecedented institutional deadlock, all the more so since the French far-right and far-left are insane. They can agree on one thing only: their loathing of Macron. All of this meant that the events of this week were foreordained.

Everyone knew the crisis would come when it came time to pass the budget. Indeed, many figured Macron would have to call snap elections to do it—back before he did so prematurely. The issue is the deficit and the debt. The deficit this year was forecast to be 4.4 percent and then revised upward to 6.1 percent. This was itself a scandal, causing the appointment of a parliamentary commission to figure out just how this had happened.

According to Camilla Locatelli, whose doctoral thesis concerned the curious way the French Treasury overestimates growth projections, “particularly in relation to compliance with EU fiscal targets,” the answer is that “France managed to escape much of the pressure from EU fiscal rules during the 2010s by playing with the technical estimates used by the EU fiscal surveillance system.”

Thanks to the French Treasury’s technical expertise and the relative weakness of domestic surveillance mechanisms, France managed to convince the European Commission that its budget figures were realistic, even when there were clear signs French growth had been overestimated to justify higher public deficits.

Despite the Eurozone crisis, it seems no one learned anything.

Why are France’s finances in such dire straits? It’s a series of things, piling up on top of each other. Macron, understanding that the French would never agree to serious reductions in public spending, bet the farm on growth. His government reduced the corporate tax rate and lowered the wealth tax, which did stimulate growth, and lowered unemployment, and turned France into Europe’s most attractive destination for foreign investors, all without breaking the EU’s mandated 3 percent limit on debt.

But then an uncooperative world saddled him with pestilence and war. France hardly had a chance to see whether growth could compensate for a shrunken tax base before Covid hit, and then, as if that wasn’t enough, the war in Ukraine erupted. A global inflation shock didn’t help. The government borrowed massively to cushion French businesses from the worst of the pandemic, and it did so very successfully. But depressed economic activity further sapped French tax receipts. Now, after decades of borrowing and giving no sign it will ever repay its debts, France is facing higher borrowing costs.

Much higher. In October, Moody’s downgraded France’s credit rating to negative, explaining that France’s fiscal deterioration was “beyond our expectations,” the risk heightened “by a political and institutional environment that is not conducive to coalescing on policy measures that will deliver sustained improvements in the budget balance.” By this, they meant it would be a miracle if the roving packs of savage hyenas in France’s parliament stopped shrieking at each other long enough to pass a budget.

By November’s end, French borrowing costs were at Eurozone-crisis levels, higher even than those of Greece, and the budget deficit was on track to exceed 6 percent of GDP, twice the EU’s limit. Brussels put France back in its “excessive deficit” monitoring program, meaning that unless France came up with serious plans to cut its debt, it faced EU fines (which obviously wouldn’t help it to cut its debt).

So Barnier had to come up with a budget that could redress all of these problems; then he had to pass it, without a majority, in a parliament controlled by lunatics, with the far-left and the far-right, together, occupying some two-thirds of the seats. He was doomed from the outset.

Barnier proposed a soak-the-rich budget that would have put 60 billion euros—19.4 billion euros in tax increases and 41.3 billion in spending cuts—back in the state’s coffers. The left spent a month crossing out all the spending cuts and replacing them with even grander proposals to soak the rich. Barnier patiently said no, and sent the budget back.

Meanwhile, Marine Le Pen tortured Barnier by making a series of unreasonable demands; when he dismayed her by agreeing to them, she changed the demands; when Barnier agreed again, she changed her demands again, and this continued until she got what she wanted: an unresolvable crisis that will wreak economic havoc on France, setting her up for her 2027 presidential bid.

Macron, no fan of Barnier’s budget, fumed in the background. He wanted, it was reported, to stick to his original lower-taxes, higher-growth plan, which he believes will work if given enough time. He declined to endorse Barnier’s efforts. Barnier allowed the debate over the budget, and Le Pen’s stalling tactics, to continue for more than a month. It’s not clear why he did, since from the outset it was obvious he would have to ram it through by means of the loathed Article 49.3 of the French constitution, which allows the government to bypass a vote, but also exposes the government to a vote of no confidence.

When it finally became clear to him that Le Pen had no intention of agreeing to anything, Barnier at last resorted to Article 49.3. France’s finance minister, Antoine Armand, went on television to beg the far-left and far-right to abstain from weakening the country for the sake of their own political interests. France, he said, had a choice: “We can still be responsible and work together to improve the budget … or there is another road, of uncertainty and … leaping into the budgetary and financial unknown.” France, of course, opted for Road Number Two.

The far-right and far-left immediately teamed up to introduce two motions of no confidence. After roundly jeering Barnier, 331 members of the 577-member National Assembly—more than required—voted to make him the first prime minister to be ejected by parliament since 1962 and the shortest-lived prime minister in the history of the Fifth Republic. For the first time in the history of the Fifth Republic, the far left and the far right voted together.

Why? It’s not entirely clear. Le Pen and Mélenchon are both on fire with the desire to run against one another for the presidency. They both know that the other one’s loathsomeness is their only hope. Le Pen is on trial for embezzling EU parliament funds. The prosecutor is asking that she be sentenced to five years in prison and barred from running for public office for five years, with immediate effect. A verdict is expected early next year. If she’s found guilty, she won’t be eligible to run for president in 2027. So perhaps, as many suspect, she was hoping to force Macron to resign, then run for president before the verdict could be rendered, daring the courts to send the president-elect to the clink. There is talk in France to the effect that she’s been inspired by Donald Trump’s example. She has already declared the prosecution politically motivated. It seems like an outside shot, to me, but then, so did Trump’s.

The far left is willing to play along with her—even if it brings her party to power, which it’s a lot more likely to do than it is to bring them to power—out of spite. They hate Macron that much. If they were furious with Macron before, they were outraged that after all the machinations, compromises, and horse-trades they undertook to prevent the National Rally from coming to power, they wound up with a sober, well-respected, center-right technocrat leading the government. In Mélenchon’s view, the left’s modest parliamentary plurality (achieved despite him, not because of him) logically meant that whatever the letter of the constitution might say, he had the moral right to be named his Excellency, President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Mélenchon, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Seas and Conqueror of the American Empire in Africa in General and France in Particular. If Macron failed to oblige him, he held, it could only be out of a pathological determination to deny the will of the people. The rest of the left, for some reason, united behind Lucie Castets, a young, pretty, municipal technocrat known for a single viral clip in which she denounces management consultants, and known for absolutely nothing else. The rest of the parliament found this suggestion laughable. France had serious problems to solve, they suggested to journalists. Be real. Macron dismissed the idea of appointing her, saying she would be immediately ousted. This was probably true—almost certainly true—but his intransigence only further infuriated the left.

Notionally, Le Pen put a match to this kindling because Barnier’s budget meant higher taxes on electricity and a delay to an inflation adjustment for pensioners. She wanted further cuts in medical aid for migrants, instead, as if that could make up the difference. (Math isn’t Marine’s strong suit.) Of course, the damage done to France’s economy by her shenanigans will result in far higher costs for the people she claims to represent. The failure to pass a new budget means that if the 2024 budget is rolled over on an emergency basis, as it’s likely to be, taxes won’t be adjusted for inflation. This will penalize the poorest families in France the most. It will mean there is no action taken to remedy the shortage of medical care in rural areas. It will hurt France in countless other ways, too, but Le Pen can and will blame all of this on Macron, so she is immensely pleased with herself. The chaos—and the attention—is precisely what she wants.

The left blames Macron for France’s precarious fiscal situation: It is all because of his unfunded tax cuts, they say. It does not strike them as a problem that France’s ratio of taxes to national income remains the highest in the OECD, or that France is the OECD’s biggest per-capita spender, with spending on pensions, alone, amounting to 15 percent of GDP. They believe Macron’s economic views have been fully repudiated by its deficit crisis. The far-right agrees. When it comes to economics, the two ends of the spectrum find themselves largely in agreement; the point of disagreement is not so much whether France should spend so much, but on whom it should spend it.

Neither the right nor the left is willing to concede that the pandemic and the war in Ukraine were wholly out of Macron’s control. Nor are they willing to concede that by borrowing so heavily, Macron kept the French economy from collapsing, and that had he done otherwise, they would have been the first and the loudest to scream. As usual, they have no use for reality, and neither does the electorate.

In a particularly French touch, France’s largest unions, who had planned a massive strike to protest Barnier’s budget proposals, learned that Barnier had resigned, contemplated the news solemnly, then announced they would go on strike anyway. (The agricultural unions are also planning to strike in protest of the deputies who voted to topple the government. The failure to pass the budget means they won’t get the millions of euros they were promised the last time they paralyzed the country.)

The parliamentarians who threw Barnier overboard began baying right away for Macron to resign, which of course he did not. His resignation would solve nothing, mind you, because France is still saddled with the same parliament; besides, the idea is ridiculous.

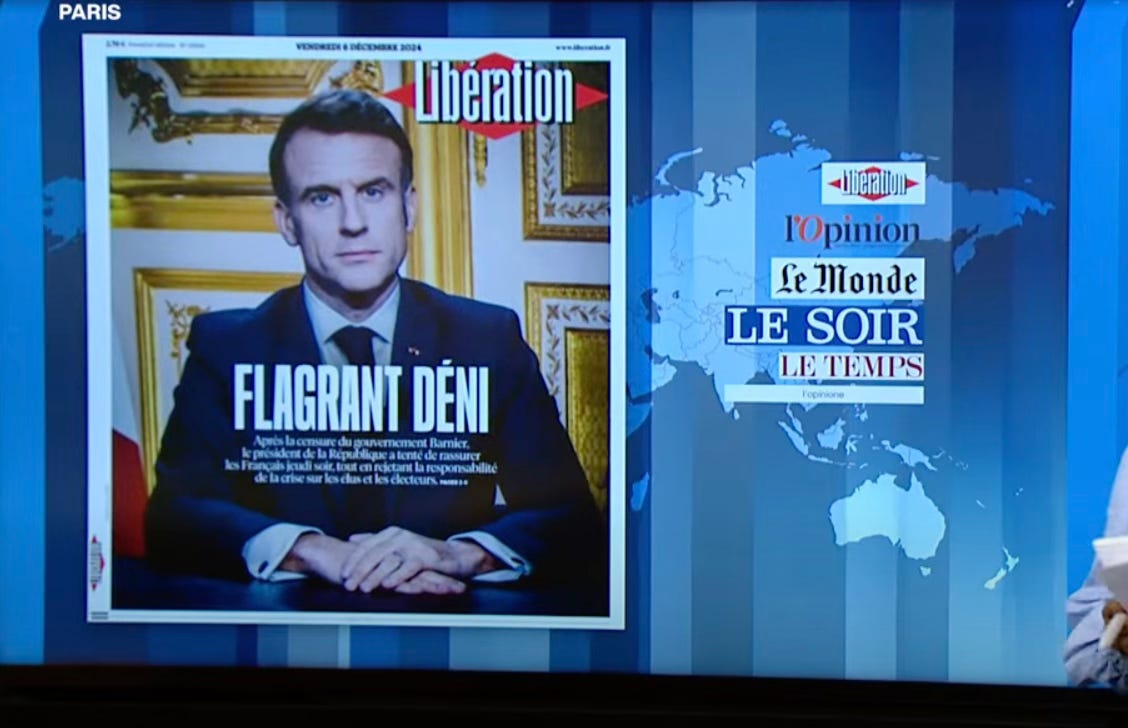

Macron addressed the nation last night to say he was going nowhere and to scold the irresponsible parliamentarians. He allowed that his decision to dissolve the National Assembly in June “was not understood,” but defended it as “necessary” to “give the floor” to voters, whatever that means. He took responsibility for this, he said, although what he meant was unclear, because he also said, “I know that some are tempted to hold me responsible for this situation,” which was much more comfortable, he said, than blaming those who ought to be blamed.

But he would “never take the blame for the irresponsibility of others,” he continued. The Popular Front had allowed itself to be the far-right’s tool. (He’s right.) The left had run on a platform of opposing the far-right, and by cooperating with them way, had “insulted the voters.” (He’s right.) As for the far right, they had “chosen disorder.” (He’s right.) Barnier fell “because the extreme right and the extreme left have united in an anti-republican front” (he’s right), “and forces that yesterday still governed France have chosen to help them.” (He was referring to the members of the Socialist Party who joined the no-confidence vote, and he was right about this, too.) “They are only thinking about one thing: the presidential election,” he said (he’s right), “preparing it, accelerating it, with cynicism, if necessary, and a taste for chaos.” (He’s right). It was an election that they want to “rush.” (Also right). But he would not be rushed. “The mandate you have democratically entrusted to me is a five-year term, and I will fully exercise it until its end.”

He said he would name a new prime minister in the coming days to form a government “of the national interest,” made up of a figures from the whole political spectrum who were “willing to participate in it, or at least, who will undertake to refrain from ousting it.”

The problem is that this was precisely what he hoped to achieve by appointing Barnier in the first place. No matter who he appoints, he’s stuck with the same parliament, split exactly the same way.

Nonetheless, he promised to end his term with “thirty months of useful action.” He finished by relieving himself of another tirade at the left’s expense, just to be sure he infuriated everyone equally: “I do not believe that France’s future can be built with more taxes, more regulation, some laxity in the face of drug trafficking, by multiplying our divisions, or abandoning our climate goals,” he intoned.

Everyone in France decided, on watching this, that if they hated Macron with the heat of a thousand suns before, they now loathed him with the heat of ten thousand suns and two microwave ovens to boot. It’s not because anything he said is obviously wrong. If it’s true that he was the fool who got France into this predicament by calling snap elections, it’s also true that the far left and far right are chaos agents who care about nothing for governing responsibility, care only about their own advancement, and have no vision for France any sane person should respect. But somehow, as always, everyone watched Macron speaking and decided they wanted to punch him. There’s something about his demeanor that the French cannot bear. It’s as if every time he opens his mouth, he calls them deplorables and says he can’t think of a thing he would change.

Me? I still like him. I’m very impressed that he got Notre Dame rebuilt in exactly the time he promised, and on budget, too. They did an exquisite job of it, from the photos.

But he really was an idiot to call that snap election.

So Europe now faces exactly what it needs least: a political and economic crisis in the heart of the Eurozone.

Europe is in a pickle. To the East, a dying Russia has gone supernova. It is determined to take Europe down with it. Russia’s sabotage campaign is so brazen that European planes are falling out of the sky. Lunatic Putin stooges keep winning elections in strategically significant European countries.2 To the West, the United States is having a lavish political seizure, about which nothing more need be said. To the South, the Syrian conflict has unfrozen. Trump is about to launch a trade war with China and send the global economy into a tailspin. Germany, the other half of the engine that powers the Continent, is almost as dysfunctional as France. The UK is irrelevant. (Elon Musk has decided that having bought the US, he’d now like to buy Britain for desert.)

France’s economic vital signs look awful. With borrowing costs soaring, French defense spending will be hit. All of Europe is endangered by France’s instability. The debt crisis in Greece nearly took down Portugal, Ireland, and Spain with it; even France and Italy began wobbling. But ten years ago, Germany had the capital—economic and political—to bail out its allies. It doesn’t, now. Volkswagen just announced the first plant closures in its history. Its own bickering coalition government just collapsed.

This bothered Marine Le Pen not a bit.

On Wednesday, Foreign Minister Jean-Noël Barrot warned, “At a time when war is on our doorstep, when the planet is in turmoil, when China and the United States want to outpace us … those who make the decision to overthrow Barnier’s government and deprive France of a budget will be responsible for the mess and disorder.”

But Le Pen is counting on voters not to care whose fault it is and to simply blame the incumbent—a tendency on which she’s probably right to count, certainly one amply demonstrated by the recent US election. She’s right that France blames Macron:

Before pulling the whole house down, Le Pen wrote an editorial, published in Le Figaro, declaring that her party would not be made “scapegoats for the incompetence of governments unfit for debate and compromise.” (This was rich, given Barnier’s willingness to bend over backwards to accommodate the unreasonable demands of a party that could not even win a plurality, no less a majority of the parliament.) Macron, she wrote,

has transformed our public accounts into a Ponzi scheme: on the one hand, all-out spending financed by a race to indebtedness, without any political vision; on the other, revenue that never arrived, due to a lack of real stimulation of French production. At the end of the road, 3,230 billion in debt, and a France that now borrows on the same terms as Greece or Spain.

What “real stimulation of French production” would involve is unclear: presumably it’s a by-product of getting rid of the immigrants. She denied the possibility that her actions could lead to a government shutdown, for which she used the English—“le shutdown”—hinting of her contempt for this American notion, and blamed everything on Macron. The risk of a shutdown was a lie, just like all the other lies:

The French have already suffered the government’s lies about the state of our finances throughout the European election campaign, then the legislative elections. Even if it meant misinforming them by waving around the threat of non-existent political risks, which led to a surge in interest rates and caused the State to lose several hundred million euros.

(Like Erdoğan, she has a novel theory of interest: France’s borrowing costs rose because the government warned they would.) She concluded with a flourish: “The real risk for democracy is not le shutdown. It’s fake news!”

As for le shutdown, she’s probably right, but Macron needs a new government, pronto, to pass an emergency law extending the 2024 budget, without which the government will just shut down on January 1, and I wouldn’t put it past this parliament of clowns to be unable to get its act together enough to prevent that.

France, of course, is wondering what all of this means. The headline in Le Point reads, “The strange defeat of Emmanuel Macron’s France.” It is an allusion to a book by the great historian Mark Bloch, recently elevated to the Panthéon. He was describing the “strange defeat” of France in the 1930s. Le Point writes:

France, following the senseless dissolution of parliament in June, 2024, is painfully paying for four decades of decline and refusal to adapt to the world of the 21st century. Emmanuel Macron’s narcissism and inconsistency have transformed a slow decline into a crisis unprecedented since the end of the Fourth Republic.

… The institutions of the Fifth Republic that were thought to be indestructible are paralyzed, and the State is sinking into impotence, a situation unknown since the abortive revolution of May ‘68. Discredited and marginalized in Europe, France is accumulating humiliations, with the latest symbol the breaking of defense agreements and the departure of our soldiers from Senegal and Chad, which definitively confirm a pitiful exit from Africa.

… The geopolitical situation is at least as tense, since the Ukrainian conflict is entering a decisive phase with the announced opening of negotiations in 2025 due to the exhaustion caused among the belligerents by a long war of attrition, the escalation of violence triggered by Russia, and last but not least the election of Donald Trump, which calls into question the military and financial support of the United States for Ukraine.

France’s plight, they write, is not owed to the French, but to “the limitless irresponsibility of the political class,”

which continues its egotistical quarrels and power games in complete disconnection from economic, social, and geopolitical realities. The prize for engineers of chaos certainly goes to Emmanuel Macron, who is devoting all his time to placing himself at the center of the ceremonies marking the reopening of Notre-Dame, without realizing that the contrast between the builders of cathedrals, brilliant and anonymous, and the egotistical gravedigger of the Fifth Republic is devastating.

But the betrayal of the national interest is just as present among the leaders of the working class, who have no concern for the economy and have, as their only compass, their position in the future presidential election. …

There is still time to disarm the infernal machine of financial panic, which ultimately implies the placing of France under guardianship by the IMF, the European Union, and the ECB. There is still time to ward off the temptation of an authoritarian experiment. … But to do this, we must break the institutionalization of lies and the irresponsibility of our leaders, who have plunged the French into anger, collective passion, and irrationality.

They conclude by calling for the return of a France without Macron, a decisive rejection of demagogy, and “a return to the reality principle and a morality of responsibility.” They cite Marc Bloch:

Our system of government was based on the participation of the masses. Now, these people to whom we thus entrusted their own destinies and who were not, I believe, incapable in themselves of choosing the right paths, what have we done to provide them with this minimum of clear and sure information, without which no rational conduct is possible? Nothing in truth. Such was, certainly, the great weakness of our supposedly democratic system, such, the worst crime of our supposed democrats.

It is all the fault of the elites, in this argument. And who would disagree that they have failed to cover themselves in glory? Some are just plain rotten. Others have failed to rise to the unusually demanding circumstances, which in the end is just as great a failing.

But something troubles me in this analysis. How is it possible, in a democracy, for everything to be the elites’ fault? Do the people who elected these elites bear no responsibility for choosing scoundrels and fools?

I genuinely don’t know the answer to this question. Bloch’s analysis is deeply paternalistic: The masses cannot be expected to know better unless their leaders provide them with “a minimum of clear and sure information.” But there will always be someone who is willing to offer the masses pleasing lies, will there not? At some point, don’t we need masses who know better than to believe the liars?

There is, for sure, something rotten in the democratic world. It seems always to come down to the same things: demagoguery, populism, an elite that simply cannot manage to meet, no less master, the moment; the pervasive sense, even though ordinary men and women live lives of luxury unimaginable to their forebears, that there is not enough money to go around; a pathological insularity that prevents citizens and their leaders alike from grasping that they live in a world on fire and haven’t the time or the luxury of insanity. Above all, these disparate democratic crises seem marked by a pervasive, extraordinary, exuberant, and petulant irrationality—a determination to live as if facts and figures simply do not matter. It is hardly unique to France.

But why?

I wish I could tell you. But I just don’t know. I wish I did.

The party’s name has been translated, variously, as “Unsubmissive France,” “France Unbowed,” and “Indominable France.” My translation, I think, gets at the essence of its philosophy. I’ve translated the names of these parties throughout because if you don’t watch French politics closely, all of this is hard enough to follow without introducing a slate of French acronyms.

Who is Călin Georgescu, the far-right TikTok star leading the Romanian election race? A Russia-supporting vaccine skeptic who praises his country’s WWII fascist leaders won a shock first-round victory in Romania’s presidential election; Romania’s pro-Europeans fear Putin is pushing them back to dictatorship. Far-right NATO-skeptic Călin Georgescu is on track to win the Romanian presidency, thanks to a Russia-influenced campaign.

Within the past 30 days, I built a scale-model (1:1000) of Notre Dame out of metal pieces. But, there was too much opportunity for imperfect positioning at each step. Perhaps I will leave it to Claire in my will.

I guess I am naive. I am astonished that French economists were allowed to cook the books for several decades without detection and punishment.

During the past four years, the American Federal Deficit increased from 1 trillion to $12 trillion.

While the situation is tragic, the way you write about it makes me smile.

Humans can be so shortsighted, idiotic or incompetent that all that is left to do is to laugh at these decedents of hunter gatherers attempting to organize themselves in the modern world they have created. The evolutionary baggage we all carry is a big part of what makes us human (for better and worse). It also makes it next to impossible for us to be perfect, but certainly, we can be way better than we are at the moment.