Javier Milei, Geert Wilders, and the English language

There's a very meaningful difference between the right and the far-right. Journalists who use these words interchangeably make everyone stupider.

I’ve spent the better part of the week working on an essay about Javier Milei, Geert Wilders, and the distinction between “right-wing” and “far-right.” It’s still not quite done. But I get intolerably anxious when I haven’t sent out a newsletter in several days. I fear that you’ll all cancel your subscriptions. So you’re going to get a not-quite-right newsletter today. Or rather, you’re going to get a newsletter that requires some reader participation: You’re going to help me to finish it.

Here’s what I’ve been trying to do. I’ve noticed journalists tend to use the terms below promiscuously and often interchangeably, almost never defining them:

conservative

libertarian

right-wing

far-right (or radical right)

populist

nationalist

authoritarian

fascist

crazy

This is a mistake. These are not synonyms. Not only do they denote very different things, it’s important for the wider public to understand the different things that they denote, along with the specific historic reasons for the stigma attached to the adjectives “far-right,” “authoritarian,” “fascist,” and to a lesser extent, “nationalist.” When journalists habitually conflate these terms, they’re not enlightening their readers, they’re making them more stupid. This is particularly reckless if the electorate is already dangerously ill-informed.

I wondered the other day if democracies can survive when the electorate falls below a certain level of competence:

Most of our citizens aren’t sufficiently well-informed to vote. They don’t know enough about anything to choose good leaders who will make good decisions on their behalf. They don’t understand how their government works. They don’t understand how the economy works. They don’t understand how the world works.

Whether democracies can survive an electorate’s ignorance is an open question. I’ve raised it, but I can’t answer it. I’m certain, though, that it is an open question, meaning that it’s reasonable to worry that democracies can’t survive widespread voter incompetence, and we should be worried that we’ve fallen below the minimal threshold. So I find it especially irresponsible for journalists to make their readers more stupid. When they describe every right-of-center politician as “far-right,” readers will conclude that “far-right” is a meaningless epithet or that being a far-right politician isn’t such a bad thing. It isn’t and it is.

Over time, sloppy word usage becomes routine. For example, much as it aggravates me, “impact” is now a verb.1 The phrase “begs the question” no longer denotes the logical fallacy of assuming a point yet to be proved; it has come to mean, “suggests a question.” Journalists have given up trying to enforce the distinction.2 There is no use telling people they’re using the phrase incorrectly. As any linguist will tell you, if the speaker and his audience both feel it’s correct, it is.

But not every change in usage is an improvement. Just as language may evolve, it may also devolve, and in this case, it has devolved. Everyone is worse off for it, because we now lack a widely-understood phrase that signifies a common logical fallacy. Over time, I fear, the public will lose any sense remaining to them that begging the question is a fallacy, or even that logical fallacies are undesirable.

This is similar to what happens when we collapse the distinction between right and far-right.

Right versus far-right

It’s reasonably easy to distinguish between the right and the far-right, and it’s reasonably obvious why we should welcome right-wing politicians, who play an essential role in any healthy multiparty democracy, while shunning the far-right, whose ideas should always and everywhere be kept outside the Overton Window—with a crowbar if necessary.

This is the difference: A normal right-wing politician respects the rules and norms of liberal democracy, and prioritizes these rules over policy outcomes, whereas a far-right politician does not. (This distinction also applies to the left and far-left.) Thus not only is it entirely possible to be a right-wing politician and a liberal democrat, that’s exactly what most of the West’s elected politicians have been since the emergence of multiparty democracy.

As for the definition of liberal democracy, recall the New Caesarism:

“Democracy” is a system of governance in which power is vested in the people and exercised by them through a system of representation involving elections. It does not entail liberal democracy. Not only is liberalism distinct from democracy, it’s often in tension with it. …

A democracy may only be termed a liberal democracy if the following rights are protected:

Right to life and security of person.

Freedom from slavery

Freedom of movement

Freedom of speech

Freedom of assembly

Freedom of religion.

Freedom to own, buy, and sell property.

Thus the following features distinguish liberal democracies from other regime types:

The purpose of the state is to secure fundamental rights for every citizen. (Usually, a constitution emphasizes the protection of individual rights and freedoms.)

These individual rights take precedence over the well-being of the collective.

Since the state has no purpose beyond securing these rights; its power is otherwise explicitly constrained.

The state is intentionally designed to limit, not enhance, its power, chiefly by separating authorities so that no branch of the government enjoys a monopoly on power.

There is equality among citizens before the law and due process for all under the rule of law.

Laws are interpreted by an impartial and independent judiciary.

State and religious authority are distinct, and there is widespread religious tolerance.

There is equality of opportunity among citizens, including women and minorities.

The democratically-elected majority respects the political opposition.

There is a broad and flourishing civil society.

There is a diverse and independent media.

There are free, fair, and competitive elections between at least two viable and distinct political parties. (Lacking these, a state may be liberal, but it is not a democracy.)

Only if all of these conditions are generally met may we call a society a liberal democracy.

Voters who don’t understand these ideas have scant hope of exercising their franchise responsibly. But to understand a concept, you need a word for it. It doesn’t matter which words we choose so long as they’re widely understood by speakers and listeners alike, they’re used stably over time, and the words we choose don’t compass so broad a range of ideas that they convey no useful information at all. When journalists use the phrase “far-right” to describe both Hitler and Margaret Thatcher, the phrase is no longer useful. The practical consequence of eroding the distinction will be the cultivation of a generation of voters who will shrug when they hear that a politician holds far-right views. A socially important stigma will be eradicated, if it hasn’t been already.

The stigma served a useful purpose. Ideally, voters would be aware of the historic reasons for the odium attached to “far right,” “authoritarian,” and “fascist” politicians. But failing that, they should know that “far-right” politicians are undesirable—“far-right” being a shorthand for “a set of beliefs and a political style associated with Hitler and Mussolini.” Even if they don’t really know much about Hitler and Mussolini, they need to understand the shorthand and sense that there is something dangerous about the far right.

Journalists can (and should) use the stigma attached to the term “far-right” to convey to their readers that something about a candidate or a platform is alarming in a particular way. Because voters don’t have as much time as journalists do to study every candidate’s style and platform, they rely upon journalists to do the initial vetting for them and convey to them important impressions about a politician. Journalists can make themselves useful by accurately labelling far-right candidates “far-right,” with all the stigma that implies. But they can’t do this unless they reserve the term for figures and movements who are meaningfully described as “far right.” If everyone is on the far-right, no one is—either that, or it’s 1922 and you’re marching on Rome.

Conservatives and libertarians

Permit me to suggest a scheme for disambiguating these words, partly based on the way they’re used in the wild and partly based on the way I think they should be used if we’re to get maximum value out of them.

“Conservative” and “radical” are antonyms. Both words describe a temperament, not a political program. So while the UK has a “Conservative Party,” and this party has a specific platform, it is possible for a Conservative politician to lack a conservative temperament. (Liz Truss, with her ill-fated budget, is an example.)

What’s more, these words only make sense if used as comparators. If you live in a society with a long-established free market, it is conservative to oppose nationalizing the commanding heights of industry. If the commanding heights of your industry are already nationalized, it is radical to propose denationalizing them overnight. The same policy goal may be conservative or radical depending on the starting point. For a highly traditional society, instituting no-fault divorce would be radical. For a society long accustomed to no-fault divorce, eradicating it would be radical. “Radical” solutions may be good or bad, depending on the problem. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation has been correctly described as one of the most radical liberations in the history of the modern world. No one means this as a criticism.

Generally, people of a conservative temperament are wary of change, particularly if it’s large and sudden, and their wariness is based in the belief that civilization takes a very long time to build; it is rare, complex, and fragile, and it’s easy to screw things up. A temperamental conservative would recoil, for example, at this proposal:

This idea could only come from a man who’s never given Chesterton’s Fence a moment’s thought. It may well be true that fifty percent of the federal bureaucracy is superfluous. I suspect it probably is. But anyone who proposes to eliminate half of it overnight and at random, without first learning what those bureaucrats do and and satisfying himself that their jobs are inessential, is a radical (and a fool).

The word “libertarian” is used in many ways, but roughly, it denotes a political philosophy that elevates, above all, the liberty of the individual. In the United States, libertarians have been strong advocates of the right to private property and laissez-faire capitalism. Because the United States was founded on libertarian principles, American libertarians are conservative. In the postwar era, this resulted in an alliance of libertarians and conservatives under the umbrella of the GOP. But there’s nothing inherently conservative about libertarianism: If you grew up in the Soviet Union, the transition to a market economy represented a radical change. During the 1991 Moscow coup, the conservatives were communists.

The word “libertarianism” does not denote a temperament. Like the word “socialism,” it denotes an ideology: a system of political and economic ideas that inform policy. You can’t be a libertarian if you believe property is theft. But whether you’re a radical libertarian or a conservative libertarian depends on your temperament and your starting point.

“Populism” is what political scientists call a “thin-centered” ideology, in that it is not a comprehensive ideology in its own right, but a patina or a style of politics. As Cas Mudde puts it:

I define populism as a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogenous and antagonistic groups: “the pure people” and “the corrupt elite,” and argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people. The core features of the populist ideology are monism and moralism: both “the people” and “the elite” are seen as sharing the same interests and values, while the main distinction between them is based on morals (i.e. “pure” versus “corrupt”). Populists claim that they, and they alone, represent the whole people, while “the elite” represent “special interests.” Obviously, “the people” is a construct, which can be defined in many different ways.

Populism is an ideology, i.e. a worldview, but it is thin-centered, meaning it addresses only part of the political agenda— for example, it has no opinion on what the best economic or political system is. Consequently, almost all relevant political actors will combine populism with a host ideology, normally some form of nationalism on the right and some form of socialism on the left. While populism does not threaten democracy in the same way as extremism did in the early 20th century, it constitutes a fundamental challenge to the main institutions and values of liberal democracy, most notably, minority rights, pluralism, and the separation of powers.

Depending how “the people” are defined, populism may divide the public among class, ethnic, or national lines; depending how politicians wield it, populism may be innocuous or profoundly dangerous; depending on the political system, it may or may not be appropriate: In some systems, it is simply a truism that the elite is corrupt, and if this is so, a dose of populism may be salutary and corrective.

“Populism” is not a synonym for “nativism,” or “nationalism,” although they often go together. “Nativism” is not a fully-developed ideology but a policy preference: A nativist favors the interests of the native-born over those of immigrants. Nationalism, too, is a policy preference. If you identify with your nation and support its interests, you’re a patriot. If you identify with your nation and support its interests to the exclusion or detriment of other nations’ interests, you are a nationalist. While the word “nationalist” is generally understood to hint at something noxious and dangerous, few could say quite why, but the reason for the word’s minatory associations, I would suggest, is that everyone grasps that unvoiced distinction, even if they can’t articulate it.

The taxonomy I’ve proposed above is of course incomplete. But if we were all to use these definitions, and use them consistently, we’d be much better off, because we’d have a shared vocabulary of useful words that describe important concepts—essential concepts, even, if you’re trying to hold on to your liberal democracy.

If you look at recent headlines, however, you’ll see that journalists are making no effort to use these words carefully or consistently. They’re using the words “right-wing,” “far-right,” “libertarian,” “populist,” “authoritarian,” “nationalist,” and “radical” almost interchangeably:

How young Argentines helped put a far-right libertarian into power

Right-wing populist Milei set to take Argentina down uncharted path

Javier Milei: From libertarian ideologue to president of Argentina

Meet Argentina’s free-market authoritarian president-elect, Javier Milei

Party of far-right populist set for stunning victory in Dutch election

Milei and Wilders elected: Is the libertarian moment finally here?

The problem is obvious: Readers cannot possibly understand what these words mean, because as they’re used here, they’re just a crude signifier: They’re meant to instruct the reader that he should not like either of these men. This will probably work if the reader is a Democrat and it will have the opposite effect if the reader is a Republican. Above all, it will leave the electorate just a bit more stupid, which we can hardly afford.

🛑 Before I continue, stop, go here, and take this test. Don’t read the instructions and don’t read the rest of this newsletter until you do. Note your score privately. Don’t overthink it, the way I always do. Just put down the first answer that comes to mind. Then come back to the newsletter.

Are you back? Good. How’d you do?

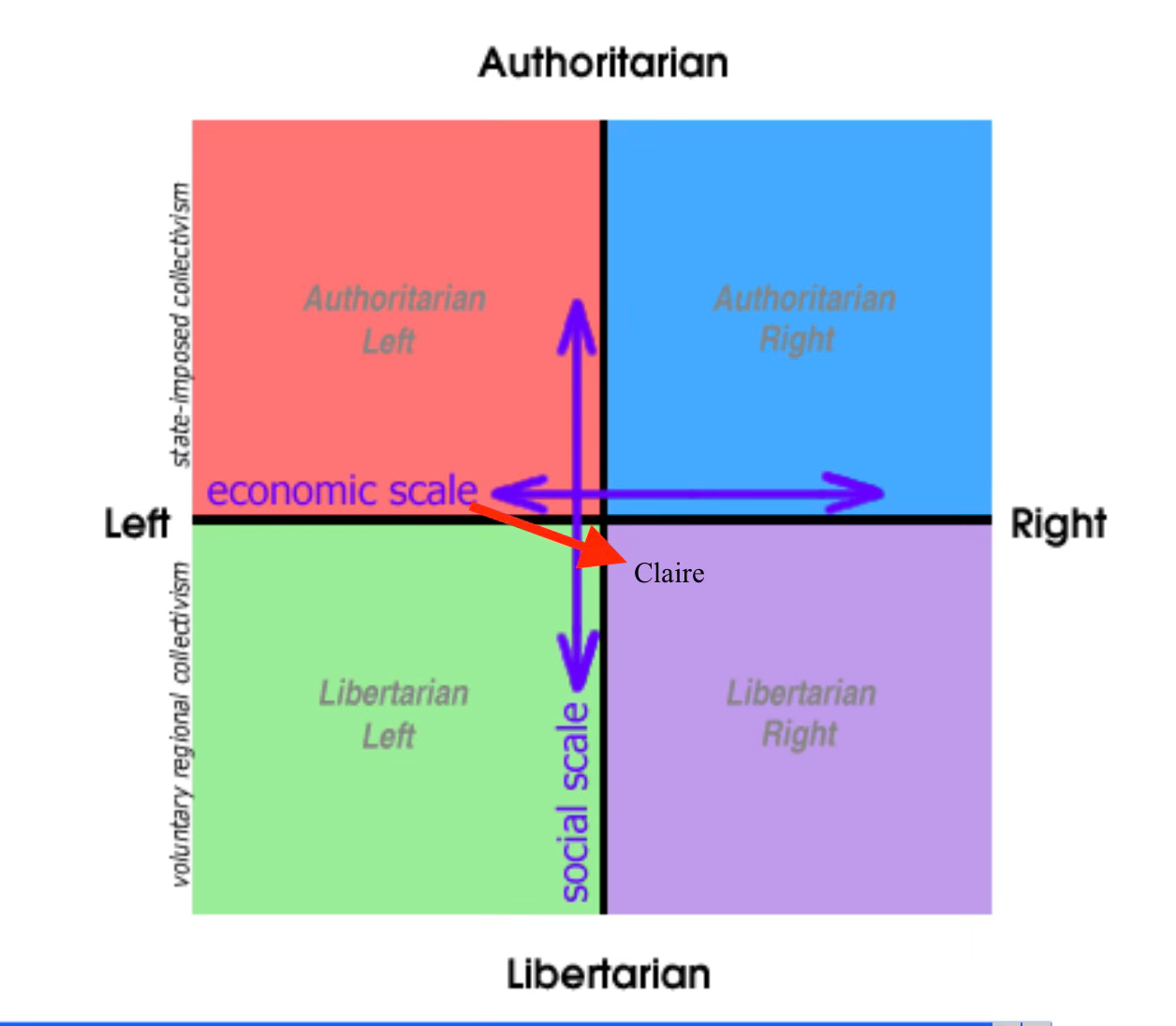

I’m not sure who came up with that test, but I think it’s useful. It’s a step in the right direction. The idea is this: We use the traditional left-right axis to describe our instincts about economic policy. The left is more likely to favor collectivism and state intervention; the right extols individualism and laissez-faire. The idea behind the political compass is that left-versus-right isn’t the only crucial axis. They suggest a second, independent axis: authoritarian versus libertarian. (They’re using the word “libertarian” as an antonym for “authoritarian.” That’s fine, so long as people know what they mean.)

Your score, whatever it is, will place you somewhere on this compass:

Using my typology, “far-right” would be the blue quadrant (or the upper reaches of it). Far left would be the red quadrant, or the top parts of it.

This is how they reckoned the 2022 French presidential candidates would score:

I think that’s about right, although Macron, I think, is slightly more to the left, economically.

But when it comes to the US, their compass doesn’t comport with my intuition. Here, for example, is their assessment of the 2020 US presidential candidates:

I’d say that if a test like this doesn’t register a very significant difference between Trump and Biden, it isn’t sensitive enough.

This is where I’m stuck. The test—and the underlying taxonomy—should be capable of discerning a massive difference between Trump and Biden. If the test fails to show that Trump is an entirely different species of political animal—and a vastly greater danger to American liberal democracy—something is wrong with the test.

I’ve been trying to figure out just what it is, so far inconclusively. It may be that the two axes are basically correct, but the propositions they’re using to measure political attitudes aren’t the ones they need.

But I suspect the problem is that the compass needs to be three-dimensional. There’s a third scale, and I’ve spent the past few days trying to figure out how to characterize it. The third scale is particularly salient in the era of Global Enduring Disorder. I haven’t yet landed on the right terms, but I’m considering these: “chaos versus order,” or “system versus anti-system,” or “legal authority versus demagoguery.”

This third axis, it seems to me, is the one we need to be thinking about when w try to understand not only the West’s current, disgruntled political mood but what, if anything, meaningfully unites a group of politicians who are all, somehow, connected to Steve Bannon, Tucker Carlson, and Vladimir Putin. (The words Bannon would suggest, I’m sure, are “globalist versus anti-globalist,” but I have no idea what those words mean and I doubt he does, either.3)

I just don’t have this idea quite clear in my mind yet. If I could work it out, it might explain my sense that Milei doesn’t truly belong to this group, even if Bannon and Tucker are thrilled by him.4

Geert Wilders’ electoral success is a genuine nightmare. The man really is a dangerous, far-right demagogue. But as far as I can see—keeping in mind that I don’t know Argentina well at all—Milei is radical, yes, but not a “far-right radical.” He may be nuts, which is a separate issue. He may also be too inexperienced to achieve anything of significance. But I’m not inherently alarmed by his political views; in fact, my instinct is that he could do Argentina some good.

I’m curious to find out if he’s right about what ails Argentina’s economy and how best to fix it. Argentina has been suffering miserably from Peronist mismanagement, with inflation above 140 per cent, foreign currency reserves wiped out, a stifling regime of currency and price controls. Nothing in Milei’s discourse suggests to me that he seeks to abrogate fundamental rights or victimize minorities. Yes, he’s emphatically a populist, but he may well be right in suggesting that Argentina’s elite are a corrupt lot who’ve immiserated the country.

I may be overlooking something important. I have not studied his thoughts extensively. I don’t live in Argentina or speak Spanish. Perhaps the journalists who are alarmed have spotted something that I haven’t yet. I certainly agree that the man looks mad as a weasel. But when I consider Javier Milei, I don’t feel the dread that I do when I consider Geert Wilders—or the despair that paralyzes me when I think about Donald Trump.

(Speaking of which, if you haven’t yet read Robert Kagan’s essay in The Washington Post—“A Trump dictatorship is increasingly inevitable. We should stop pretending”—you should. He’s right.)

You can help

So this is where I’m stuck, trying to figure out exactly what the third axis is, and how to measure it. Since I can’t quite work it out—not, at least, without failing to send out a newsletter today, which is unacceptable—maybe you’ll join me in thinking it through. Here’s what I suggest.

Below, I’ve chosen a few articles about Wilders and Milei that are reasonably comprehensive and not excessively polemical. (Skip the ones above, unless you have loads of extra time.) Read them through, then take the test—first on Milei’s behalf, then on Wilders’. Tell me their scores in the comments, then tell me if those scores make sense to you, intuitively. (Also, tell me your instinct about Milei: Do you also sense that he’s not really part of the Bannon Family? Or am I missing something?)

Then help me answer this question: Is there a third axis? If so, what is it? What propositions, like the propositions in the original Political Compass test, could we use to measure it? Are there propositions that would allow us to measure only this quality, as opposed to “authoritarian versus libertarian,” or “left versus right?”

On Javier Milei:

An interview with Javier Milei (This is especially useful because these are his own words. Despite his protestations of sympathy with Trump and the media’s tendency to call him “Argentina’s Trump,” I just don’t see that the two men share any important quality, except perhaps for being controversial. Do you?)

Javier Milei, presidential candidate: “It’s super easy to dollarize Argentina’s economy.” The right-wing libertarian sat down with EL PAÍS to discuss his radical proposals to reform his country’s economic system. He declares himself to be against “anything obligatory,” including compulsory voting.

Javier Milei, a mixture of a messianic preacher and a rock star. The economist and TV panelist—who is the far-right candidate for the presidency of Argentina—ended his campaign by abandoning his chainsaw and tempering his rhetoric and proposals to win over skeptical moderates

The ultra-right libertarian and “anarcho-capitalist” who represents angry Argentina. Abused as a child and perpetually enraged as an adult, the far-right candidate won in the first round of the presidential elections after capitalizing on the vote of fed-up Argentines and setting the political agenda with his histrionics.

Tired Argentinian politics give victory to far-right libertarian Milei.

Javier Milei, telepathic conversations with dogs (and God) a troubled youth, and the issue of mental health.

Who is Argentina’s controversial chainsaw presidential candidate, Javier Milei?

Argentina in the emerging world order. In recent years, Buenos Aires has sought stronger ties with China and membership in the BRICS. But with the recent election of far-right president Javier Milei, Argentina’s approach to the world may change.

Argentina’s Javier Milei: the radical who could blow up political status quo

On Geert Wilders:

Far-right anti-Islamist Wilders wins Dutch election, sending shockwaves through Europe

Will Geert Wilders lead the most right-wing government in Europe? After winning the most seats in this week’s election in the Netherlands, the hard-right Party for Freedom will decide the next government.

A unique party: The PVV as a party organization (I don’t know how to get it to start at the beginning of the chapter, but I mean the whole chapter.)

Offensive, hostile and unrepentant: Geert Wilders in his own words

“The biggest problem in the Netherlands.” Understanding the Party for Freedom’s politicization of Islam

Omtzigt won’t enter Cabinet talks with Geert Wilders “at this time” in new blow to PVV

Wilders arrives in Parliament to PVV cheers; Experts question legality of their policies

Foreign Defense Ministers concerned Wilders government will pull support from Ukraine

If we manage to figure this out, we can build the 3D political compass together and test it out on each other. Perhaps it will help us all to describe and understand this phenomenon with a bit more rigor.

Oh, since I expect you’re curious: I forgot to save my test results before closing the window, but my score was just slightly to the libertarian right—and you have to admit they got me dead to rights:

What’s your score?

But please, for the love of God, stop using it that way. When you say, “Our community has been severely impacted,” you instantly evoke a likeness between your community and your colon.

We have not. It is forbidden and will always be forbidden by our Style Sheet. If you’d like to read more of my grumpy animadversions about word usage, this essay is for you: I hereby rise to the defense of the Académie Française.

Taking a leaf from Stalin, Bannon and Carlson have hinted repeatedly that globalists and Jews overlap on the Venn diagram. Certainly, many of their fans think so. But beyond this, I don’t think “globalist,” as they use it, has a stable meaning.

Sohrab Ahmari, however, shares my view that Milei is not really part of this group. You can almost see Sohrab struggling here with his impulse to call Milei a “right-deviationist.”

I'm in the purple quadrant, as I expected. 4.38 Left/right, and -1.64 social libertarian/authoritarian. So, somewhat to the right of Claire economically, but not far off socially. But I could have told you that already!

Ironically, I think conservative vs. radical might capture somewhat the third dimension you’re describing. The defining feature of the Tucker/Bannon crowd is a commitment to deliberately eroding social trust and attacking the credibility of legacy institutions. They want to break central pillars of global stability that have been erected and refined over generations. (e.g. NATO, liberal democracy, etc...). Wouldn’t that make them almost the paradigmatic arch nemesis of real conservatives?