My sweet, beautiful cat Féline died yesterday at 11:35 am. She was the last of my seven-cat family and the delight of my life.

In the three weeks between her diagnosis and her death, my plump, lustrous cat became a skeleton with fur. What an evil, obscene thing cancer is.

Just last week, my veterinarian told me she thought the prednisolone would slow the spread of the disease and be sufficient to control the pain. The tumors were still small, she said.

Prednisolone certainly gave her an appetite, which delighted me, because my standard heuristic is that any cat who’s eating isn’t ready to die. I figured the more she ate, the longer she’d live. So I ordered every species of cat treat for her from Amazon, and I began heating up her meals to encourage her. Cooked food was a revelation to her. She was so excited by it that her whiskers twitched and she grunted happily while devouring it, getting it all over her pretty little face.

Afterward, though, she was too tired to wash herself, even though she’d always been so fastidious. She always spent hours, every day, patiently cleaning her fur down to the very last snow-white hair, then doing it all over again. She knew she was the most beautiful of the cats. When we imagined my cats with the power of speech, my brother and I reckoned she was saying, “Aren’t I pretty? I’m pretty, aren’t I. Isn’t my fur fluffy? I’m the prettiest of the cats. Daisy isn’t anywhere near as clean as me. I think I’d look nice wearing a ribbon.”

(Suley, by contrast, would play Hamlet. Or Catlet, as we reckoned it.)

But who knew this vain, fluffy airhead of a cat would be so remarkably brave? Two days after her leg was amputated, she hopped out of her cat carrier as if a fourth leg had always struck her as a vulgar excess. She hopped from one corner of the apartment to the other, purring with delight to be home. She never once complained. I’d worried that at her age she wouldn’t be able to adapt, but she was absolutely unfazed. The loss of her leg interfered with none of her pleasure in life. She even still went on the occasional wild sprint through the apartment to celebrate an especially righteous bowel movement. I’m light, I’m light!

But she was too tired now for her beloved beauty rituals. I cleaned her fur and her muzzle and her paws with a warm washcloth, which she appreciated. I warmed cat food in every flavor and texture for her: soup, mousse, chicken, beef, lamb. I gave her fishy-smelling broth to keep her hydrated. I gave her chicken-flavored treats, tuna from the can, shrimp-flavored goo, salmon sticks, freeze-dried duck, and liverwurst sticks—she scarfed it all up, probably wondering why the hell it had taken me twenty years to learn to prepare a decent meal.

It always delighted me to watch her devour her food. It made me laugh, too. Why did such an angelic creature—so pure, feminine, so exquisite—love eating such disgusting things? She should have been eating cucumber sandwiches with the crusts cut off and petits fours, but she just loved the nasty stuff. She remained very much an animal, even when she ate from my hand.

It didn’t matter what I fed her or how much she ate. She just kept losing weight. She grew more tired every day, and her world got smaller and smaller, until it was just the bathroom and my bed.

But she didn’t seem to be in pain. She purred when I stroked her, and she jumped on me in the morning to wake me up with her warm breath and a little chhhhiirrrrirp. I wondered if maybe it could go on this way a little longer.

It couldn’t. On Saturday night, she tried to stand up and let out a pitiful cry. (It always happens on Saturday, when my veterinary clinic is closed.) Something was preventing her from using her hind leg, the only one she had. She tried to drag herself to the litter box on her two front paws, panicked. The sight was intolerable. I called the emergency vet service.

They sent over a lovely guy. We all liked each other. Féline was curious and friendly. He was gentle with her. She seemed to enjoy being examined, treating him as if he were just another guest who’d come to admire her beauty and pet her (though goodness this guest was doing something strange with that thermometer). Her heart was fine, he said, and so were her lungs. Her temperature was perfect.

I explained that she wasn’t in distress unless she tried to stand. When he palpated her hind leg, he found a lump on her inner thigh. He showed me where it was. I could feel it, too: It felt like a small gum ball. He would usually suspect a ganglion cyst, he said, but given her diagnosis, a new tumor seemed more likely. There was no way to know for sure without doing the kinds of tests I’d promised never to subject her to again.

He said we could try giving her painkillers to see whether they stabilized her enough to give her a few more good days. She was fully alert, and just hours before, she’d eaten a big meal. If there was a reasonable chance of controlling the pain, I said, I wanted to try. So he gave her an injection of Buprenorphine—which she absolutely loved. She rolled on her side and began purring immediately, stoned out of her mind. We both laughed. He was very gentle with her. He agreed with me that she was astonishingly sweet. He gave me a week’s worth of Tramadol and told me it would either let her enjoy a bit more life, or it wouldn’t. If not, I had his number.

What was the best-case scenario, I asked? Perhaps his answer was colored by the desire not to break my heart, because he said, “A few more weeks, or even—at the very outer limit—maybe months.” I doubted it. She was so thin. But it was nice to hope. At least it didn’t have to be that night.

She was relaxed and comfortable now, thanks to the bupe. (I didn’t realize that the doctor not only spoke English, but understood it well enough to laugh when he heard me whispering to her, “Say thank you to Dr. Feelgood.”)

She stayed that way through the night. She wasn’t in pain, but she was so stoned she could barely lift her head, and she peed in my bed. I put the sheets in the wash and reassured her it wasn’t a thing to be ashamed of. We were friends. Friends let friends pee in their bed when they’re too stoned to find the litter box.

In the morning, I gave her the Tramadol. She couldn’t stand the taste and she gagged, then spit it out. So I had to force her to take it—she struggled and cried, and she wouldn’t look at me afterward and I felt like a monster.

Her appetite remained good, but the Tramadol wasn’t enough. She kept trying to stand up, whimpering, then lying down again, exhausted and confused. I sent my father a video of her. He called me right away. She’s entering the zone. Don’t wait too long.

That evening, she stopped eating out of my hand. She turned her face away when I offered her a treat. I thought it might be because she’d felt so betrayed when she realized I’d slipped a nasty-tasting Tramadol into her liverwurst. Then she tried to stand again, and when she let out another frightened cry, I knew there was no more hope. I couldn’t let her suffer like this.

I picked her up and helped her to use the litter box. I brought her to the sofa and caressed her while she sat on my lap. I told her the vet would come back in the morning. I told her, too, that I’d help her to get to the litter box whenever she needed it—she didn’t need to try to get there on her own. It was fine if she peed on the bed, too. Just be comfortable. We’ll sleep near each other one last time. Tomorrow there will be no more suffering.

She did the most touching thing. She buried her face in the palm of my hand, so that my hand cupped her soft little head completely, covering her eyes. It was a completely submissive, trusting gesture—as if she wanted me to shield her from the sight of something frightening. When I moved my hand to stroke her, she sought it out again to do the same thing. She hid her face in my hand like that, insistently, for about fifteen minutes. I’ll never know what exactly it meant. Was she afraid to die? Was she saying goodbye? Did it sooth a pain? I can’t know. But it moved me deeply.

I gave her another dose of pain medication, which she accepted meekly if only from exhaustion, and I brought her to our bed. The drugs left her stupefied to the point of being limp. I put her on my chest, skin to fur. I didn’t think I’d be able to sleep at all, no less sleep like that, but somehow I did—I fell into a deep sleep.

When I woke up, we were in exactly the same position. She was still on my chest—warm, soft, breathing. She hadn’t moved. I realized she was no longer conscious. I laid her down gently on the bed and called the emergency vet. She’s dying, I said. I don’t want her to suffer. Please come. But the operator said the vet who had come on Saturday, the one I liked, wouldn’t be available until Friday.

She’s dying, I repeated. We need help now.

She said she’d see whether another vet could come. She would call me back.

I stroked her. Although she wasn’t responsive, she did seem peaceful, as if she was just sleeping. I don’t know how long she and I stayed like that. She was breathing gently on the white sheets, surrounded by lush plants, the light pouring through the high windows, and I was stroking her head. It was a beautiful place to die, I thought. She looked so thin. Her fur was so soft, and her little body so warm.

We waited.

She loved to purr and often purred for no reason at all, or no reason beyond an inexpressible feline satisfaction. She always sat near me while I worked, purring her head off, overbrimming with kitty-contentment. You could hear her purr from the other side of the apartment.

When Zeki and Suley died, the only thing that consoled me was seeing how happy it made Féline. I love my sofa. I love my radiator. I love it that those awful big cats are dead. She was delighted with herself for having outlived them all. Now everything was as it should be. As it was meant to be. Purrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr …

While we waited for the vet, I found the sound of a cat purring on the Internet, just as I did when she was a terrified kitten. We listened to it while we waited. I don’t know if the purring comforted her. Probably, she was too far gone by that point to be aware of it. But it comforted me.

The vet didn’t come. Féline was now somewhere very far away, completely unresponsive, even when I touched her gums or the inside of her ears. We waited.

Then she began to pant. I called the vet again: Please, hurry up. I don’t want her to suffer.

Yes, he’s trying. It’s hard to find a parking space.

Her panting grew more labored. I stroked her head and told her to stay calm. Help was on the way. I crushed up the last of a Tramadol tablet in water and gave it to her with an eyedropper. To my surprise, she swallowed it—she was thirsty. I prayed this didn’t mean she was conscious of struggling for oxygen.

I keep asking myself if she suffered, well aware that I’ll never know, that the question is pointless, that it’s completely unanswerable, and besides, she’s not suffering now. I keep asking myself anyway. I wish I’d thought to ask Dr. Feelgood for some Valium so I could have protected her from panic at the end.

I couldn’t stand it that she was gasping for air. I expected, though, that within seconds, I’d hear the doorbell ring, and then she would have the flooding relief of the sedative before she took her last breath.

I so much wanted her last experience of life to be one of perfect peace. I hope I didn’t convey to her, through the tension in my body, that I was angry the vet hadn’t come and anxious because I feared she was suffering. I only wanted her to feel that I was calm and she was safe. I thought the vet would arrive within minutes and we’d have a chance to relax together for one last moment. But he didn’t and we didn’t. She arched her back, gasped one more time for air, and died.

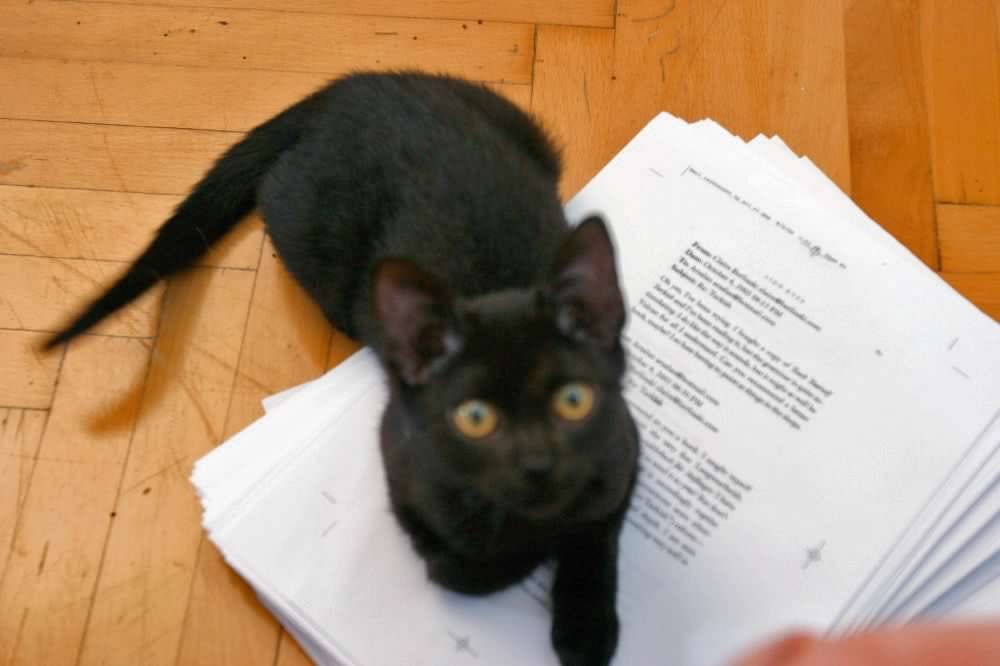

They’re all gone, now. All seven of my cats. I found them all when I lived in Istanbul, each one a kitten in dire straits. I found Féline first. Then I found the Smudge, who was dying of flea anemia in the middle of a crowded market. She was a tiny black thing with the most intelligent eyes. Everyone was walking past her as if she wasn’t even there. I sat down, thinking I’d share my lunch with her. I certainly didn’t mean to bring her home—I already had a cat. But she was every bit as intelligent as she looked: She crawled right into my lap, looked up at me, and purred. That was that.

She spent a touch-and-go week at the vet’s. Then she came home with me. Féline nearly went mad with jealousy, and I attended my brother’s wedding with a bright patch of ringworm on my face.

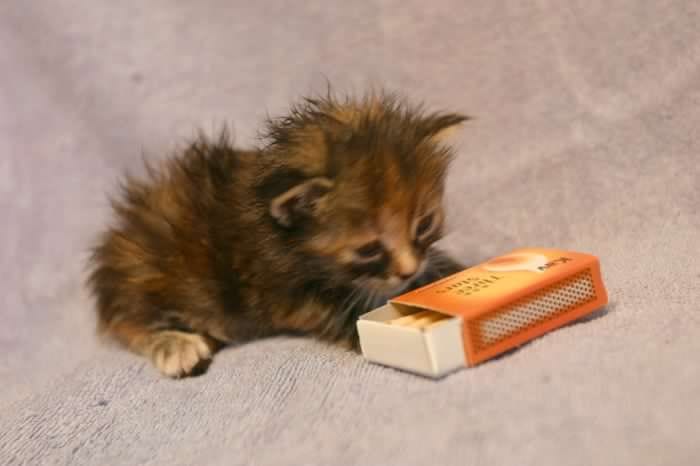

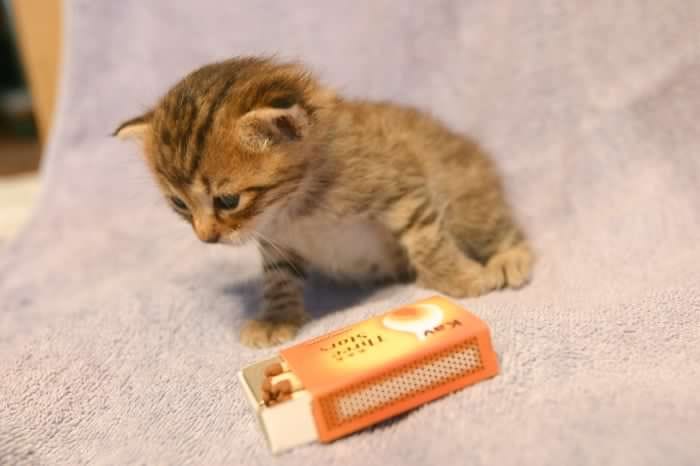

No one in her right mind sets out to adopt seven cats. I had no intention of it. But several months later, when the summer heat broke, I went out with David to enjoy the cool evening. We took a river boat up the Golden Horn to the Eyüp Sultan Camii. As we walked through the mosque, a boy rushed in with a cardboard box full of tiny kittens. Their eyes were barely open. Their mother, he told us, had just been killed by a dog. He wanted to help them, but his own mother wouldn’t let him bring them inside. He came to the mosque because God loves cats. His idea was to find another nursing cat and see whether she’d adopt them.

They were so tiny. They were crying with hunger. They were famished. Their eyes were barely open. It was getting cold out. There was no way they’d survive the night unless someone brought them indoors where it was warm and fed them kitten formula, round the clock, with an eyedropper. I’d raised three kittens just like that (Thailand, flowerpot) and I knew it was a full-time job.

I hadn’t seen any nursing mothers that evening: Kitten season was almost over. And the poor little things were just crying their lungs out. They so much wanted to live.

David tried to convince me to look at anything but the kittens, correctly sensing what I was apt to do. The boy spotted and ran after a big orange cat who looked to him like a hopeful new-mom prospect. I could tell even from where we were standing that it was a tomcat; he had balls the size of Florida. The kid’s heart was in the right place, but he obviously knew nothing about cats. Even if by some miracle he found a nursing mother, he wouldn’t know how to introduce kittens to her. He’d probably try to attach them to her tail.

I looked at David. He said no, we could not adopt five more cats—it would be insane. I said something about maybe just feeding them until they were old enough to make it on their own, he said we’d never find good homes for them in Istanbul, I said we couldn’t just let them die, he said we couldn’t save every cat in Istanbul, I said no, but we could save these cats, and the next thing I heard was the night watchman at the mosque advising the teenager that the kittens had to be be drowned, and that was that: I now had seven cats.

I have no idea why JD Vance thinks cat ladies are unhappy. Every single day with them—every minute—was a joy. I’ve never been happier in my life than I was when they were kittens. Lehmann Brothers still gazed upon the world like the moai of Easter Island, journalists were still paid a dollar a word, I could still make money by writing spy novels, and I spent all day playing with kittens. What could make a woman happier?

They made me laugh so much. They were such innocent goofballs. The love I felt for them was so intense and so uncomplicated. Each one was so adorable, each in a completely different way. Every corner of my home was full of life—grunts, purrs, meows, squeaks—and little whiskered faces sleeping or purring or chirping or scratching or licking their paws. Every night, we snuggled up in fur and love.

Yes, it was a zoo. Yes, Mo had a habit of chewing through my expensive computer cords. Yes, I accidentally trained them to wake me up when they heard the call to prayer. Yes, they peed in my houseplants. Yes, my clothing has been covered in cat fur for twenty years. Yes, I’ll be eating cat food myself when I’m old because I spent it all on vet bills. Yes, I’ve heard every cat lady joke ever made. Yes, everyone assumes I must be insane. But if that’s insane, I don’t want to be sane. Nothing I’ve ever done has given me more joy than rescuing those cats.

I would do it over a million times.

The last five years have unrelenting. Toshiro died first. Then Mo. Then Daisy. Then the Smudge. Then Zeki, and then, cruelly, just one week later, Suley. But until now, at least, there was still at least one cat left. I didn’t have to face the empty bowls.

The apartment is so empty that I feel like I have a phantom limb. Or seven.

No matter what you do, you feel guilty. I know I tried so hard to care for them as best I could. I know that every living thing dies. I know it’s absurd to think I could suspend the laws of nature. Yet I feel that in letting them die, I betrayed them.

I was supposed to protect them. They thought I had God-like powers. They thought life would go on forever. They loved their warm hammock over the radiator, the sunbeams, the safety of my home. They loved chasing the paper balls I threw for them and chattering at the birds. They had no idea that one day their sturdy little bodies would fail them. They figured that if I could protect them from dogs and the cold and hunger and loneliness, I could do anything. They couldn’t understand why I didn’t protect them from death. Neither can I.

I knew from the very first that I’d wind up with a broken heart. I’ve dreaded it for twenty years. And now it’s here.

It’s just so sad. I just miss them so much.

One writes, that `Other friends remain,' That `Loss is common to the race'— And common is the commonplace, And vacant chaff well meant for grain. That loss is common would not make My own less bitter, rather more: Too common! Never morning wore To evening, but some heart did break.

I'm so, so sorry, friend.

These kind comments are more consoling than anyone who wrote them probably realizes. I'm taking great comfort in them. Thank you.