I’m sending the Turkey items separately so you can more readily prepare for the chat, here on Substack, at 6:00 pm Paris time today, or noon EST. (Besides, Turkey always presents the “Europe or Middle East?” problem when I compile these summaries. I seem to be unable to make a decision and stick with it. In truth, it really is both.)

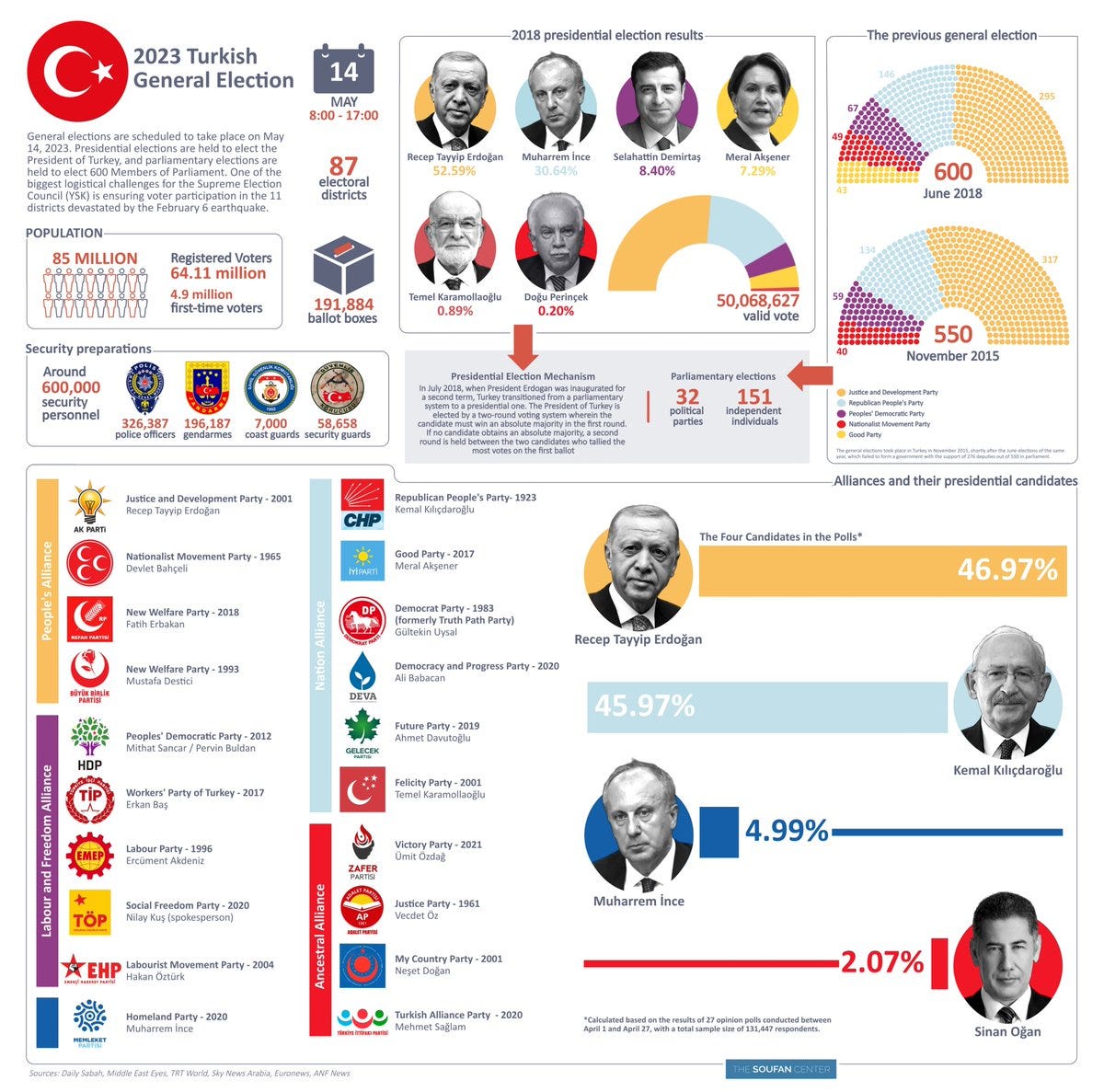

Summary: Muharrem İnce, Chairman of the Turkish Country Party, has withdrawn his presidential candidacy just three days before the election due to a hateful campaign against him, including the circulation of fake slanderous images online. İnce’s withdrawal will boost the main rival of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. Despite doubts about whether elections can remove an autocrat like Erdoğan from power, recent developments suggest that his popularity has declined. In the 2018 presidential election, Erdoğa captured 52 percent of the vote, but he now faces a different political landscape. The failed coup’s “rally-around-the-leader” effect has diminished, nationalism has become a growing opposition force, and the country is grappling with a major economic crisis. Furthermore, the opposition is more united than ever, with six parties forming an alliance supporting Kılıçdaroğlu, who commands 50.9 percent of the vote, according to the latest poll. However, Erdoğan still has a strong following. The election will be closely monitored by civil society organizations, and despite concerns about fairness, it is expected that the votes will be counted correctly. The foreign policy positions of the candidates differ, with Erdoğan focused on the fight against the PKK and YPG and pursuing closer ties with Russia, while Kılıçdaroğlu aims to strengthen democracy, ease Turkey’s isolation, and pursue a more balanced approach to foreign relations. The outcome of the election holds significant implications, both domestically and internationally. A defeat for Erdoğa would be a victory for liberal democracy worldwide and could improve Turkey’s relations with the West, repair relations with neighboring countries, and lead to economic and political reform.1

Big news ➜ One of Turkey’s presidential candidates withdraws from the race:

Muharrem İnce, Chairman of the Turkish Country Party, announced that he withdrew his presidential candidacy three days before the election. İnce said he withdrew from the race because of a hateful campaign waged against him, with fake slanderous images posted online. Muharrem İnce was one of four candidates running in Sunday’s election. His withdrawal could mean a potential boost to the main rival of President Recep Erdoğan, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu.

Claire—outstanding. He served no purpose in this race save to drain votes away from Kılıçdaroğlu. This makes me much more optimistic.

Read this one if you only read one article ➜ Turkey’s earthquake election. The disaster highlighted the corruption and authoritarianism of President Erdoğan. Can he finally be defeated?

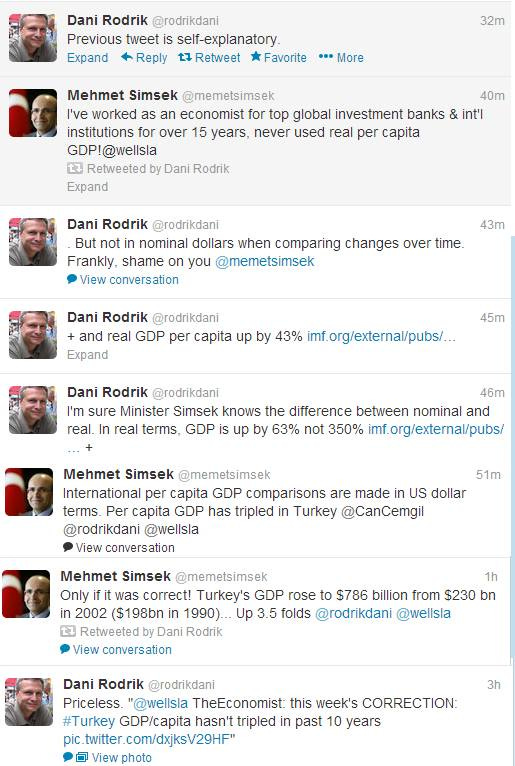

This superb article by Suzy Hansen, whose writing about Turkey I’ve long respected, is marred by a major mistake—one that’s been repeated so often in the media that it has acquired the status of fact, even though if you stop to think about it for even a second, it’s ludicrous.2 No, Turkey’s per capita GDP did not triple in the first decade of Erdoğan’s rule. Here’s the economist Dani Rodrik explaining this to the Turkish finance minister:

This is excellent, too. This should be the second thing you read, or hear ➜ 🎧 Potential for regime change in Ankara. Eric Edelman, the former US Ambassador to Turkey, hosts Gönül Tol, the founding Director of the Turkey Program at the Middle East Institute. She discusses her new book, Erdoğan’s War: A Strongman’s Struggle at Home and in Syria, and her perspective on the upcoming Turkish elections:

They discuss the complex inter-relationship between Erdoğan’s foreign policy and his domestic aspirations to move Turkey in an authoritarian direction, Erdoğan’s thirst for power and his pragmatism in pursuing Islamist, socially conservative and Nationalist constituencies as circumstances have changed, the impact of twenty years of AKP rule on Turkish society, and the prospects for the united opposition “Table of Six” in the election. They also touch on the potential for election fraud and Erdoğan refusing to leave office despite the outcome of the vote. Finally, they touch on the reaction of civil society and the mess that the opposition will inherit if they win the elections.

This is a much more sophisticated discussion of Erdoğan than you’ll usually hear. Also, her analysis is correct: She’s absolutely right to say that Erdoğan is best described, above all, as a populist with a flexible ideology (as opposed to an Islamist, a liberal, or a nationalist). I only regret that she didn’t challenge Edelman about some of his mistakes during his tenure in Turkey, but she was far too polite.

You can also read the transcript here, although the transcript quality isn’t great—the software they used couldn’t handle the Turkish names.

More by Gönül Tol: Yes, Erdoğan’s rule might actually end this weekend. Elections still matter in Turkey, and not every strongman is strong:

Can elections remove an autocrat like Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan from power? If you pose this question to Turkey watchers in Western capitals to get their take on the country’s upcoming election, you will get a resounding “no” from a significant number of them. Some will say Erdoğan is still very popular—or at least adept at mobilizing his followers. Others will argue that elections do not matter in the entrenched autocracy he has built; one way or another, he will find a way to stay in power. Take the Western conventional wisdom about this Sunday’s election with a grain of salt, and here’s why.

Erdoğan is indeed a popular leader. He commands somewhere between 40 percent and 45 percent support, no small feat after 20 years in power. But he is not nearly as popular as he once was. In the 2018 presidential election, Erdoğan captured 52 percent of the vote, or some 26 million votes. Several factors worked in his favor then. The elections were held just two years after the failed 2016 coup and its “rally-around-the-leader” effect. Erdoğan was riding high on a wave of nationalism after the Turkish military intervened in the Syrian civil war to fight the Syrian Kurds. The country was not suffering from a major economic crisis like today. The opposition was fractured: The popular Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) co-chair Selahattin Demirtas, Iyi Party leader Meral Akşener, Republican People’s Party (CHP) candidate Muharrem İnce, and Felicity Party leader Temel Karamollaoğlu were each on the ballot running separately against Erdoğan. The nationalist base was more unified, with the majority still backing Erdoğan; the nationalist breakaway Iyi Party had been established too recently to draw away much of the vote.

Fast-forward to 2023. To win the election, Erdoğan has to capture more than the 26 million votes he secured in 2018 because Turkey’s voting population has grown. His problem is that he faces a dramatically different political context that makes that task very difficult. The failed coup’s rally-around-the-leader effect is long gone. The wave of nationalism that Erdoğan once rode has come back to haunt him: There is now a growing nationalist opposition to Erdoğan, with several nationalist parties peeling away votes from his far-right ally, the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). The Turkish economy has plunged into a major crisis, with runaway double-digit inflation and soaring food prices. Most importantly, the opposition is more united than it has ever been: Six parties have come together under the Nation Alliance banner and a single presidential candidate, CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, with additional backing from the pro-Kurdish HDP. Altogether, Kilicdaroglu commands 50.9 percent of the vote, according to the latest poll.

However, as she points out:

A smarter option for Erdoğan would be to accept the result and wait for the new government to fail. He still has a strong following he can mobilize for this purpose. Given the enormous economic problems an inexperienced new government would have to address, surging back through democratic means is not impossible—especially if the current opposition makes good on its pledge of switching to a reformed parliamentary system, which would open a path for Erdoğan to return to power as prime minister.

By Hugh Pope: The battle of the Turkish centuries. Erdoğan will never match up to modern Turkey’s founding father—and he suffers from Atatürk envy:

Erdoğan’s Turkish Century—announced last year—continues [his] long-standing, implicit challenge to Atatürk’s imposition of Western ways and a narrow idea of Turkishness. And at home, this fuzzy neo-Ottoman culture has so far featured a museum, built outside the Byzantine walls, celebrating the 1453 conquest of Constantinople with startling realism; the reconsecration of Aya Sofya as a mosque; and a mentality that leans on state employees to attend Friday prayers as communal obligation.

But abrupt changes make it hard to speak of a consistent vision for Erdoğan’s Turkish Century that could match Atatürk’s Kemalist ideology. Authoritarianism is now back in force, economic missteps mean the Turkish lira has dropped to one-tenth of its value from a decade ago and annual inflation is over 43 percent, while internal conflicts fester. The EU accession process has stalled, Muslim neighbors have proven uninterested in a neo-Ottoman older brother and external conflicts simmer.

Why Kılıçdaroğlu suspects Russian interference:

Turkish opposition presidential candidate Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu shocked many on Thursday when he openly accused Russia of trying to interfere with Turkey’s presidential and parliamentary elections in two days’ time. “Russian friends, you are behind conspiracies, deep fake content, and tapes that were revealed in this country yesterday,” Kılıçdaroğlu tweeted in Turkish and Russian. “If you wish for our friendship to continue after 15 May, take your hands off the Turkish state.”

Kılıçdaroğlu’s claim came as breakaway opposition candidate Muharrem Ince withdrew from the race on Thursday, citing an online smear campaign he maintains is fake. Ince gave few details, though fake sex tapes and doctored pictures showing him cheating on his wife have reportedly been circulating online in recent days. A senior Turkish opposition official [said] that there were many reasons to suspect Moscow’s interference in the elections in Turkey, citing the close ties between Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin. “They have been funding Erdoğan’s election campaign promises through several steps for the past six months with billions of dollars,” the official said. “Funding through the Akkuyu nuclear power plant, deferral of gas payments and so on and so forth.” … The Turkish opposition official said Putin also helped Erdoğan by brokering talks between Ankara and Syria at a time when Erdoğan has come under fire over the presence of nearly 3.7 million Syrian refugees in Turkey.

I have no doubt Russia wants Erdoğan to win and is taking active measures to that end. That said, the Ince sex tapes are classic Turkey, and many possible culprits suggest themselves. (Sex tapes are a Gülenist specialty, for example.)

The Economist writes, If Turkey sacks its strongman, democrats everywhere should take heart:

As we report, the election is on a knife-edge. Most polls show Mr. Erdoğan trailing by a small margin. Were he to lose, it would be a stunning political reversal with global consequences. The Turkish people would be more free, less fearful and—in time—more prosperous. A new government would repair battered relations with the West. … Most important, in an era when strongman rule is on the rise, from Hungary to India, the peaceful ejection of Mr. Erdoğan would show democrats everywhere that strongmen can be beaten. ...

Like autocrats the world over, Mr. Erdoğan has cemented himself in power by systematically weakening the institutions which limit and correct bad policy—and which his opponents, a six-party alliance with a detailed plan for government, promise to restore. … Like so many other strongmen, Mr Erdoğan has neutered the judiciary, via a tame legal-appointments board. He has muzzled the media, partly through intimidation, and partly through the orchestrated sale of outlets to cronies, another common ploy. He has sidelined parliament, via constitutional changes in 2017 that gave him discretion to rule by decree; Mr. Kılıçdaroğlu promises to reverse this. Mr. Erdoğan’s prosecutors have intimidated activists and politicians with trumped-up “terrorism” charges. Turkey’s political prisoners include the leader of the main Kurdish party—the country’s third-largest, which is threatened with a ban. The (opposition) mayor of Istanbul faces prison and a prohibition from politics. Former government heavyweights are scared to criticize the president, demanding anonymity before discussing him in whispers. All this will get worse if Mr. Erdoğan is re-elected, but rapidly improve if he loses. An opposition victory would also be good for Turkey’s neighbors, and of huge geopolitical value to the West. Turkey these days is almost completely estranged from the rest of Europe, though it is still, nominally, a candidate to join the EU. That may never happen—but a President Kılıçdaroğlu pledges to honor the judgments of the European Court of Human Rights, and to start to release Mr Erdoğan’s political detainees. Europe should respond by reviving a long-stalled visa program for Turks, improving Turkey’s access to the EU’s single market, and cooperating more closely on foreign policy. With the strongman gone, Turkey’s rift with NATO should start to mend. Its block on Sweden’s accession to the alliance would be lifted. Relations with America, poisoned by Mr. Erdoğan’s cozying up to Vladimir Putin and attacks on Kurdish forces in Syria, would improve. However, a new Turkey would maintain Mr. Erdoğan’s policy of walking a tightrope over Ukraine. It would keep supplying Ukraine with drones, but not join sanctions against Russia; it relies too much on it for tourists and gas.

More important than any of this is the signal an opposition victory would send to democrats everywhere. Globally, more and more would-be autocrats are subverting democracy without quite abolishing it, by chipping away at rules and institutions that curb their power. Fifty-six countries now qualify as “electoral autocracies,” reckons V-Dem, a research outfit, up from 40 near the end of the cold war. The list could grow: Mexico’s president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has been trying to undermine the country’s judiciary and electoral authority. If Mr. Erdoğan loses, it will show that the erosion of democracy can be reversed—and suggest how.

Seriously idiotic article of the day ➜ Why Europe is desperate to see Erdoğan lose:

The Economist has surpassed itself in its clearly expressed hatred for an elected head of state, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. In its latest edition, it casts the Turkish presidential election as the most important that will take place this year, and claims that not just the future of Turkey but the future of democracy itself will hinge upon the result. … This is an enormously stupid thing to say. It may have escaped The Economist’s attention but Turkey—under the hyper-presidential rule of a strongman-is a country where a free election can still take place, in contrast to a region where dictatorship is the norm.

And this election is free. It’s ferociously populist, polarized, and undoubtedly an uneven playing field in the access opposition parties have to the state media. But it is free and hard-fought. Despite the Supreme Electoral Council’s decision in 2019 to cancel the initial victory of Istanbul opposition mayoral candidate, Ekrem İmamoğlu, on the grounds that the vote was too close (he won with a bigger majority in the rerun), Turkey’s electoral system is still robust.

Um, no. No, when you’re cancelling the opposition’s victories, your electoral system is not robust. Who is this dickhead? He’s clueless and completely missing the point. Oh, and apparently, the real reason the Economist objects to Erdoğan is “because Erdoğan has fashioned Turkey into an independent state with its own powerful armed forces, that will not automatically toe the line dictated to it. This is the reason he has so many enemies in the West.” This whole article sounds as if it was dictated by one of the AKP’s press flacks. Read it to learn what an AKP press flack sounds like.

An Erdoğan defeat would mark a victory for liberal democracy worldwide:

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğa may be the most defining leader of the early part of the 21st century. His two-decade rule has transformed the face of his country and cemented a political style that prefigured the rise of numerous nationalist demagogues elsewhere. In 2003, the year Erdoğan came to power, the Freedom House think tank wrote confidently of “liberty’s expansion” around the world and hailed glimmers of change in notoriously sclerotic, statist Turkey under Erdoğan’s religiously minded Justice and Development Party, or AKP. This year, its annual report placed Turkey at the heart of a more than decade-long global “democratic recession.”

Erdoğan’s own evolution over the past twenty years also tells a story about the trajectory of global politics in that time. He was a liberalizing reformer who powered an economic boom as prime minister in the first decade of the century. As Turkish dreams of accession into the European Union faded and financial crises convulsed the West, he turned southward and eastward and settled into the role of a religious nationalist bent on rolling back the draconian legacy of decades of Kemalist secularism. In the aftermath of the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, he used his soft-Islamist clout to push a Turkish model of democracy for the region.

Nope. All wrong. Read what I wrote here. The account above simply wrong. Returning to the same article,

And the longer he remained in office, the clearer it became that the president’s sole mission was to consolidate and hold onto power. By the 2020s, the Turkish model under Erdoğan represented something altogether different: A blueprint for indefinite electoral autocracy built on majoritarian grandstanding, divisive culture wars, anti-Western grievance and paranoia about domestic and foreign plots—not to mention the capture of key state institutions, the intimidation and arrest of dissenters and civil society members, and the steady erosion of the country’s free press.

Yes, but this was perfectly clear in 2003. Seriously. This is a completely invented narrative.

… But all of that may pale in comparison to the symbolic message Erdoğan’s loss would strike. ““It will say something about the future of democracy across the world because we’re talking about an entrenched autocrat who has been there for 20 years,” Gönul Töl, author of “Erdoğan’s War: A Strongman’s Struggle at Home and in Syria,” told me during a briefing hosted by the Middle East Institute think tank in Washington. “If he loses power via elections, that will give a lot of people hope that the autocratic surge can be reversed.”

About this, I fully agree. But Turkey’s problems will not be solved. Getting rid of him is a necessary but far from sufficient condition for that.

Why Turkey’s upcoming elections matter so much for the world:

Perhaps no European nation will be watching Turkey’s election more closely than Sweden, whose bid to become a NATO member has been held up by Erdoğan. Though Turkey voted last month to allow Finland to join the military alliance—doubling NATO’s land border with Russia—Erdoğan continues to hold up Sweden’s bid for membership, citing Stockholm’s refusal to extradite “terrorists” affiliated with the militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK.

Kılıçdaroğlu’s chief foreign policy adviser, Ünal Çeviköz, told Politico in March that he would not stand in the way of Sweden’s NATO ambitions: “If you carry your bilateral problems into a multilateral organization, such as NATO, then you are creating a kind of polarization with all the other NATO members with your country,” he said.

In truth, if Erdoğan wins he’ll probably approve Swedish membership, since obstructing it is an election ploy.

Will Turkey’s elections be free and fair?

While allegations of fraud have marred previous votes, elections are still free in that opposition candidates are permitted to run — and despite the erosion of democracy under Erdoğan, Turkish civil society has maintained a rich tradition of election monitoring, Tahiroğlu said. “I do think it still could be a free election,” she said. “And by that I mean that on the day of May 14 when people vote, that those votes will, by and large, count, and the results will be, by and large, correct.”

That’s because groups including Turkey’s oldest election monitoring organization, Vote and Beyond, send out tens of thousands of volunteers to polling stations across the country to monitor the vote, including the official count. “Because the stakes are so high, they’re mobilizing at a level I’ve never seen before,” Tahiroğlu said.

Vote and Beyond isn’t that old! Or wait, maybe I’m that old. But yes, they do a great job. This election won’t be free and fair, but most of the unfreedom and unfairness is behind us—the vote will probably be counted correctly. We might see a few electrical outages in key districts, which the AKP will attribute to a cat getting caught in the transmitter. The real question, as the article notes, is whether RTE will accept the outcome.3

A delegation from the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, which visited Ankara last month, raised concerns about the logistics of voting in areas devastated by the February earthquakes.

That’s a serious concern. Most of the provinces struck by the earthquake were AKP strongholds. The head of the Supreme Election Council recently said that more than a million voters were expected not to vote owing to their displacement. Continuing the article,

Freedom House gives Turkey a score of 2 out of 4 for the fairness of its elections, citing criticism of the 2018 general elections by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, which accused the AKP of misusing state resources to gain electoral advantage and Erdoğan of falsely portraying political opponents as supporters of terrorism. “The judges of the Supreme Electoral Council, who oversee all voting procedures, are appointed by AKP-dominated judicial bodies and often defer to the AKP,” the Freedom House report finds.

Freedom House is correct.

Ahead of the election, Erdoğan has turned to his tried-and-true tactic of stoking culture wars. And he has deployed massive public spending this year—offering tax relief, cheap loans and energy subsidies—to woo voters.

He does that every time.

Erdoğan’s tight control over the media has tipped the public narrative in his favor. And under his rule, the judiciary has jailed or brought charges against critics—including Istanbul’s popular mayor, Ekrem İmamoğlu, who is from Kılıçdaroğlu’s party. İmamoğlu was convicted in December of insulting state institutions in a case widely seen as politically motivated. He has appealed the verdict.

No, not fair. There’s a real chance he could lose anyway.

Related: Rigging the Vote Won’t Be Easy for Erdoğan. Ahead of Turkey’s election, civil society organizations have mobilized a record number of volunteers to monitor and protect the polls.

Erdoğan’s challenger vows to end “authoritarian rule”:

Kılıçdaroğlu said he would prioritize repairing Turkey’s economy and strengthening democracy while ending “authoritarian rule.” In foreign policy, his administration would ease what he said was the country’s “isolation” around the world and restore power to a diplomatic corps sidelined under Erdoğan. Analysts say Kılıçdaroğlu is likely to preserve Turkey’s ties to Russia, an important commercial partner, though he has criticized Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine.

Relations with the United States would be more “balanced” under his administration, he said, mentioning Turkey’s suspension from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter jet program after Erdoğan’s decision to buy an air defense system from Russia. Kılıçdaroğlu did not say how that dispute would be resolved. Of the Russian air defense system, the S-400, he said, “Turkey currently owns the most expensive scraps in the world.” …

Some of Kılıçdaroğlu’s other policies hew to bedrock nationalist positions, including criticism of US support for a Kurdish-led militia in Syria affiliated with the militant Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK). “We know that the terror organization is receiving weapons from the West. We also know that the terrorist organization is financed by the West,” he said. But he added that Turkey must be part of what he called “Western civilization,” a term he said included non-Western democracies that respect human rights and have a balance of powers.

How will the vote affect foreign policy?

Despite western criticism, Erdoğan will resume the fight against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) in Syria and Iraq, while continuing to pursue normalization with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. In the Eastern Mediterranean, Libya, and the Aegean Sea, Erdoğan will likely welcome reasonable solutions. Normalization with Greece and Egypt is what Turkey wants, but reciprocity is key.

… Erdoğan will cooperate with Moscow on energy. But Ankara’s position may change if the Ukraine war deepens or spreads, because it opposes the region’s destabilization. Turkey’s priority is to stop the fighting and reach a negotiated solution. It won’t stop “talking to both sides” and seeking balance, an approach that facilitated the grain corridor. … While Erdoğan pursues normalization and bilateral/multilateral cooperation across the Gulf, the Balkans, the Caucasus and Central Asia, the Middle East will take top priority as he works to reinforce political normalization and fix problems in fragile places such as Libya, Syria and Yemen. Developing relationships with the Turkic world and turning the Organization of Turkic States into an effective collaborative mechanism will also be at the forefront of Erdoğan’s agenda.

[B]ringing together nationalist, leftist and conservative parties, the opposition Nation Alliance has an ambiguous foreign policy vision. That would likely challenge Kılıçdaroğlu if he wins. … It won’t be easy for Kılıçdaroğlu, if elected, to find common ground among contradicting political views on Syria, Libya, Iraq, the Aegean, the Eastern Mediterranean and counterterrorism. “Turning to the West” remains Kılıçdaroğlu’s clearest foreign policy goal, particularly with regards to jumpstarting the EU admission process and complying with European Court of Human Rights rulings—which would mean releasing Kurdish politician Selahattin Demirtaş and activist Osman Kavala from prison. In truth, even redefining terrorism likely won’t revive the EU process, because Europeans expect structural changes that are incompatible with Turkish foreign policy. Furthermore, membership talks will not stop Greece and Greek Cypriots from making maximalist demands.

It would be difficult for the opposition to pursue rapprochement with the West and to distance Turkey from Russia, as this would mean disrupting the post-2015 balance with Russia, and sparking crises over Syria, counterterrorism, refugees and energy—which would be problematic for both Ankara and Europe.

Some good points above.

Turkey holds elections every five years. Presidential candidates can be nominated by parties that have passed the 5 percent voter threshold in the last parliamentary election, or those who have gathered at least 100,000 signatures supporting their nomination. The candidate who receives more than 50 percent of votes in the first round is elected president, but if no candidate gets a majority vote, the election goes to a second round between the two candidates who received the highest number of votes in the first round.

Parliamentary elections take place at the same time as the presidential elections. Turkey follows a system of proportional representation in parliament where the number of seats a party gets in the 600-seat legislature is directly proportional to the votes it wins. Parties must obtain no less than 7 percent of votes—either on their own or in alliance with other parties—in order to enter parliament. The second presidential ballot, if it takes place, will be held on May 28.

The media will begin reporting at about 9 pm local time, which would be 2 pm EST, and we should have informal results by midnight.

Correction: In an earlier version of this newsletter, I misstated the time results will be available. I apologize for my carelessness.

Söner Çagaptay is the author of both of the articles below (and in the same publication!) which indicates, I suppose, the way Turks are torn between optimism and pessimism:

How the earthquake could spell the end of Erdoğan’s rule

How the levers of state—and powerful friends—could help Erdoğan win his toughest election.

On the one hand …

… It took a natural disaster to shake the Kemalist state to its core. The devastating earthquake of 1999 destroyed industrial areas along the outskirts of Istanbul. What ensued proved to be a game-changer for Turkey’s citizens: in their time of need, the father state was nowhere to be found as thousands lay injured under the rubble, waiting for help from relief agencies that never arrived. It took days, and in some cases weeks, for government relief to reach some communities. That failure left the pretense of a severe but effective Kemalist state in tatters. A massive economic crisis the following year put the final nail in the coffin of the Kemalist devlet baba. Turkish citizens not only felt abandoned by the state but also no longer feared it. The door was now open for Erdoğan.

On the other ….

Erdoğan’s greatest strength is his control of information. Given his overwhelming influence over the Turkish media and the fact that around 80 percent of the population is unable to read languages other than Turkish, shaping the message has become one of his most powerful tools for winning votes. Many people have gone to social media platforms in search of free news, and Erdoğan has taken steps to rein those in, as well. In 2020, Parliament, under the control of the AKP and its ally, the ultra-Turkish-nationalist Nationalist Action Party (MHP), passed a social media law that forces global platforms that want to operate in Turkey to open offices in the country, making them subject to sanctions and fines if they fail to respond to government directives to ban or limit content. Meanwhile, the few independent Turkish TV networks not controlled by pro-Erdoğan businesses have been slapped with exorbitant fines and taken off air for days if they run content falling outside the approved government narrative.

Accordingly, news coverage has been highly selective. Inflation, which reached as high as 85.5 percent in 2022, has hardly been mentioned. Neither has the government’s disastrous response to the earthquake: more than 50,000 people died, some while buried under the rubble waiting for help that never arrived. Also absent are stories about the massive and growing corruption of the ruling elite, including the president and his family; the epidemic of femicide (including the death of a young woman who, while working as a nanny, died suspiciously in the home of an AKP parliamentarian); government human rights abuses; the jailing of journalists and politicians; and other potentially damaging revelations about the AKP and Erdoğan. Instead, citizens are fed a continuous stream of news about Turkey’s growing status as a major international power, including stories about the country’s first domestically produced car, the recent discovery of natural gas deposits in the Black Sea, and the first Turkish helicopter-carrier naval vessel. Never mind bread-and-butter issues such as jobs and food prices or freedoms and liberties: citizens are told to embrace Erdoğan because he is an amazing leader who is making Turkey great again. …

As for the economy, Erdoğan has also been helped by growing ties to fellow autocrats, such as Russian President Vladmir Putin and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. During last year’s inflation crisis, Prince Mohammed transferred US$5 billion to Turkey’s central bank to help keep the economy afloat. Russia’s state-owned corporation Rosatom provided a similar amount in July 2022 to finance a new nuclear plant in southern Turkey, the Akkuyu Nuclear Power Station; that transfer trickled across the economy, helping stabilize the currency. …

As he has done in the past, Erdoğan is also using Turkey’s electoral system to his advantage. Crucially, in 2022, he pushed through a law that will increase the chances that the AKP and the People’s Alliance can maintain control of Parliament. In the Turkish electoral system, the presidential vote procedure is straightforward: a winner can be chosen by gaining more than 50 percent of the vote or, if no candidate achieves that, by winning a runoff between the top two first-round finishers. But the route to controlling Parliament is far more convoluted, owing to Turkey’s recent tradition of electoral alliances. In the past, seats were apportioned primarily based on aggregate votes, a system that favored the strongest alliance. Anticipating that the opposition’s alliance would be stronger than his own in the 2023 election, however, Erdoğan succeeded in having the parliamentary electoral law changed. Now, instead of the largest alliance, the new law favors the largest party, which in Turkey’s multiparty system is still the AKP. Given how close the race is, this change could be enough to give Erdoğan’s People’s Alliance an extra 10–20 seats—enough to win a parliamentary majority on May 14 even if Erdoğan himself does not come out in front. …

The Turkish presidential contest may be the most consequential election this year. Either Erdoğan will lose, giving Turkey a chance of restoring full democracy, or he will win and likely remain in power for the rest of his life. If he does so, any remaining independent institutions, including courts that have not yet fallen into his grasp, think tanks, universities, news outlets, and the foreign ministry, are likely to completely lose their autonomy, with important ramifications for not only Turkey’s political system but also its foreign policy. To Putin’s great delight, although Turkey would probably remain in NATO, a reelected Erdoğan could act more assertively as a spoiler, undermining alliance unity alongside Orbán in Hungary.

It is still possible that Kılıçdaroğlu’ could deny Erdoğan control of the chaos narrative and convince voters to abandon the sultan. The opposition leader has already shown that he will not follow the president’s path toward demonization and polarization. And it seems possible that he could come out ahead on May 14. But Erdoğan has years of experience manipulating the political system to his advantage, and he has put in place a robust strategy for staying in power. Together with Orbán, Erdoğan invented populist authoritarianism in the early twenty-first century, and even as this model has since been copied by leaders elsewhere—including former U.S. President Donald Trump, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, and former Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro—Erdoğan remains its best practitioner. And unlike most of his counterparts, he has so far proved impossible to vote out of power.

We will see, tomorrow.

Join us to discuss this, soon, on Substack chat.

It’s ChatGPT. I’m in a hurry to send this before 6 pm.

That such a mistake got past the New Yorker’s vaunted fact-checkers is dismaying. I sent them an email about it. I’ll be curious to know if they correct it. But that aside (and a few other small matters, probably only of interest to Turks and Turkey obsessives), the article is outstanding.

If you’d like to understand what he’s capable of doing if he doesn’t accept the outcome, I wrote three articles in 2015—after the June election resulted in a hung parliament—that should give you a very good idea. That result gave rise to a similar wave of Western giddiness, which everyone has now forgotten. It resulted in what Turks now call the summer of hell:

Don’t rejoice yet: Erdoğan could still win. Forming a coalition in Turkey will be a nightmare, and the strongman has the trump cards.

Erdogan isn’t finished. The game isn’t over for Erdoğan and the AKP. Now would be a good time for the West to pay attention to what’s going on in Turkey.

It’s all about the palace. Erdoğan’s message to Turks: Vote correctly next time!

It will take a bit of concentration to follow the story—Turkish politics are labyrinthine—but it will give you a good idea what we’re dealing with.

Wish I could. Sorry to miss it. Will there be a recording?

Claire you’re not in the United States, you’re an American in Paris.

Can I ask why you agree with those tweets?