Epistemic chaos and the Delta Variant, Part II

Making sense of confusing claims about vaccinations: A guide

Can any person say what may be the consequences of introducing a bestial humour into the human frame after a long lapse of years? Who knows beside, what ideas may rise, in the course of time, from a brutal fever having exercised its incongruous impression on the brain? Who knows also, that the human character may undergo strange mutations from quadruped sympathy; and that some modern Pasiphae may rival the fables of old ... 1

—Benjamin Moseley, denouncing Jenner’s smallpox inoculation

By Claire Berlinski

I saw a tweet yesterday addressed to Claire Lehmann, the editor of Quillette.2 The author, whom I’ll call Mr. Bam Boozled, wrote, “Trying to figure out who the experts are is a challenge. I’m pro-vaccine. It’s just that there’s so much obvious chicanery at the moment among health professionals, it’s hard to get a read on the truth.”

This series is for Mr. Boozled. It’s about how to approach a problem like this—specifically, how to evaluate a claim about the safety and efficacy of a medication or therapy.

If you can read this essay and you’re willing to put in several days of hard work, you can evaluate both of these propositions without overmuch reposing your confidence in someone else’s credentials:

Getting vaccinated against Covid19 is far safer than not getting vaccinated.

The evidence that ivermectin might substitute for mRNA vaccines is weak.

But you can’t do this by using YouTube University. Or any other social media platform. For all the reasons I discussed here, those are corrupted sources. If the information you get from those sources is justified, true, or useful, it’s an accident.

This doesn’t mean, however, that there is no such thing as justified, true, and useful information. Nor does it mean that this information is somewhere you’ll never find it, so why even try. Nor does it mean you should just pick the best-sounding expert—the one with the best podcast, whose political views you mostly agree with—and say, “That’s my guy. I’m outsourcing the brainwork to him.”

There’s a method you can use to answer these questions reasonably well, and I’m about to show you every step.

First, a few remarks about healthcare professionals. I don’t know what’s caused Mr. Boozled to think health professionals are beset by “obvious chicanery.” I’ve never met him. But I’m certain if I put the question to 100 random Americans, the number one answer would be this letter:

As of May 30, we are witnessing continuing demonstrations in response to ongoing, pervasive, and lethal institutional racism set off by the killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among many other Black lives taken by police. A public health response to these demonstrations is also warranted, but this message must be wholly different from the response to white protesters resisting stay-home orders. Infectious disease and public health narratives adjacent to demonstrations against racism must be consciously anti-racist, and infectious disease experts must be clear and consistent in prioritizing an anti-racist message.

The letter, supposedly, was signed by 1,200 healthcare professionals, but if you look closely at the list of signatories, you’ll note that quite a few have odd credentials. Or none at all. But never mind that. If reading this letter caused you to think, “Have I been right all my life to trust healthcare professionals? They seem to be galactically stupid,” that’s a good sign. It means your powers of observation and reason are such that you’ll sail through my class.

The number two answer, I’d guess, would be the publication, in The Lancet, of a letter signed by eminent virologists castigating anyone who asked whether Covid19 might have emerged from a lab as a scientifically illiterate racist conspiracy theorist. Since later it came to light that this letter was owed to a genuine conspiracy, I can see how that might shake your confidence.

Number three might be, “They told us we didn’t need to wear masks, even though that wasn’t true, because they were worried we’d hoard them all and there wouldn’t be enough for the healthcare workers. Then the very person who told us this lie nonchalantly admitted it was a lie. But he still has a job, and I don’t.”

Or perhaps, “When asked by a US Senator about the research the NIH had funded in Wuhan, Dr. Fauci feigned high dudgeon, weaselled on a technicality, then pretended the question itself was outrageously ignorant and impertinent.”

Mr. Boozled may have some other scandal in science and medicine in mind. If so, he should subscribe and ask me my opinion of it. This week, as a bonus to new subscribers, I will stoutly denounce the outrage of your choice and agree with you that the health professional in question is a gibbering scoundrel. Offer limited to one per customer. While supplies last.

Yes, every one of these incidents represents a grievous breach of the public trust. You get it. I get it. We all get it. Some health professionals are liars, idiots, or both.

But I wonder: Is this truly a surprise? Did you labor until recently under the impression that there were no scoundrels in the medical profession? Or might you perhaps be using the unsurprising fact that some medical professionals are scoundrels to justify a view you want to hold; to wit, that a medical professional who is telling you to do something disagreeable—eat less, say, or get vaccinated—is a lying scoundrel? f that’s what you’re doing, surely you see that this is an error in reasoning. If not, I will show you:

Exercise 1: Assume the statement, “I do not want to do x” is true. Which of the following conclusions are entailed by that statement?

x is bad advice.

the expert who advised me to do x is an idiot.

The guy who told me not to do x is an expert.

See?

More important: What does it mean if Dr. Fauci lied to you? What does it mean if a whole series of richly-credentialed experts have been in the news lately owing to some outrageously stupid thing they said or some egregious scientific fraud they committed?

Does this mean all healthcare workers are all liars? Does it mean the whole discipline of medicine is a fraud? Should we conclude there is no such thing as a correct answer to a medical question?

No. Because you know who wasn’t the subject of a billion tweets and Facebook posts? The 579,98,800 healthcare professionals who looked at that letter and thought, “Geez. That’s actually not a great public health message. Nope, that makes no sense at all. In fact, that’s maybe the worst public health message I’ve ever seen.”

Or the ones who didn’t see it in the first place because they were up to their elbows in someone else’s bodily fluids. So why didn’t you hear their opinions about whether it’s wise, under any political context, to join a large group amid a lethal respiratory pandemic and scream at the top of your lungs? Because hearing them wouldn’t have made you madder than a Mexican jumping bean, so your eyes might have wandered away from the screen. Then you wouldn’t have bought anything.

Rule Number 1: Remember the denominator. On any given day, in a free country of 328.2 million people, you can count on there being idiots who will say something galactically stupid or perpetrate a monstrous fraud.

These events make the news because they’re unusual. Only 0.01 percent of America’s healthcare professionals signed that letter. (Even fewer if, as I suspect, no healthcare professionals actually signed that letter, just a bunch of drunk college students.) There are 59 million healthcare workers worldwide. Only 0.0020339 percent of the world’s healthcare workers signed the letter. You don’t need to worry the next healthcare worker you trust will be one of them.

News, by definition, is unusual. You never see this headline: “Local tree still there.” If you read about a scientific fraud, it’s because it’s an unusual event, not one so typical no one thinks it’s news.

Above all, you saw the story about that caused you to conclude the medical profession was full of chicanery because social media entrepreneurs saw it too, realized the effect it would have, and dropped it into your news feed, rubbing their hands, waiting for you to click like a rat in a Skinner Box, shake your fist at the heavens, damn the healthcare professionals, and retweet the hell out of it—perhaps with a few catchy and original hashtags like #BigPharmaScamdemic and #BigTechBrother, ensuring everyone in your social network, and even people beyond it, saw a lot of advertising.

Rule Number 2: Our information ecosystem is broken. If you saw it on social media, it wasn’t because it was important or true. It was because it enraged or entertained you.

What about the lies, though? Should we conclude that because Dr. Fauci lied, healthcare professionals always lie?

No. This gets important here, so pay close attention.

Dr. B is in the house!

Dr. Fauci is not just a healthcare professional. He’s also a skilled power player at the top of a massive Washington bureaucracy. If we assume Dr. Fauci is a perfectly representative sample of some larger class or group, we still don’t know whether this group is healthcare professionals or skilled power players. This is called a confounding variable, or a confounder.

So let’s use science to figure this out.

Let’s do an experiment, in the old-fashioned tradition of empiricism. We’ll take 50 healthcare professionals and 50 Washington power players and put them in a box. People who badly want to get out of a box, we hypothesize, will be tempted to lie. We’ll watch them and count who lies the most. Then we’ll know for sure which group is more likely to lie.

Bill Barr’s in the box. He shouts, “Lemme out! I got rights!”

Honest enough. He’s good.

Dr. Latissimus Dorsi III, MD, PhD, Interim Chair of Anatomy at Angela Davis (formerly Lincoln) University, is in the box. “Lemme out!” she cries. “I’ve got to be in the operating room in fifteen minutes to perform life-saving surgery!”

Operating room? Him? We sigh. We check the box marked “Liar.”

This feels good. We’re doing science. Been a while since we’ve done that. We’re getting back in the groove. One by one, the men in the box sort themselves out—liars, liars, liars, liars, truthful!, liars, liars, liars, liars, liars, liars, liars, liars—and after two hours, we call it a day and leave them in the box so we can write up our research. Turns out only Tom Vilsack, some pediatric oncologist from Rochester, and—very much to our surprise!—Rudy Giuliani proved truthful. (Or he was clearly sincere, anyway, when he told us what he would do to us if he ever got out of that box.)

So, question settled! You’re twice as likely to lie if you’re a healthcare professional than you are if you’re a DC power player. Obviously, Fauci lied because he’s a healthcare professional. Science says.

We write up our results excitedly. Clearly, this is an astonishing finding with immediate relevance to global health. Once people know they should never trust a healthcare professional, it will save their lives!

We submit our article to a prestigious medical journal and we wait.

When the phone finally rings, though, the editors don’t sound as thrilled as we imagined they’d be. After a few gruff pleasantries, they say, “Did you realize Vice Admiral Murthy was in the box?”

“Yeah, so what?” We are annoyed. They are holding up the publication of our lifesaving research. We drum our fingers on the table.

“Murthy is both a healthcare professional and the Surgeon General of the United States.”

“Come on. We don’t have time for this nitpicking. We’ve made an astonishing discovery. Publish it before the Nobel committee calls and we get too tied up to talk to you.”

But these editors are blockheads. They start rabbiting on about “other things that might cause a man to lie.” Then they start riding our asses about the “sample size”—of all stupid things, when lives are at stake! “Isn’t it possible these results were just, you know, chance?” they ask.

We shake our heads. These guys are like—Betas. Beta-minuses. We look at each other. Why are they putting up this weird … resistance?

“There’s another little problem,” pipes up one of the management-school dweebs. “You knew who the power brokers and the doctors were beforehand.”

“So?”

“Couldn’t that have influenced whether you thought what they were saying was true?”

We smack our heads. As if it would make any difference if we confused Mitch McConnell with a pediatrician? A lie is a lie, right? Are they saying we can’t tell the difference between truth and a lie? “What are you talking about!” we explode. “We are highly skilled experts who have been saving lives for years by doing experiments like this! Don’t you see the signal—”

“We think it would be best to have a randomized—”

“What is your fetish?” We slam down the phone. Yet another bunch of editors with this bizarre aversion to saving lives! What is up with their groupthink! How can they be so blind?

Suddenly, it strikes me. Yes, you and I have just done Science. But this goes beyond Science.

I almost can’t believe it. The thought that has come to my mind—why, it couldn’t be true. No. No! But what else to make of the evidence before me? I fall to my knees, cross myself, and tremble. “Bam,” I say, “No. These editors aren’t total idiots.”

“What? Of course they—”

“No. It’s worse.” I gather myself, dab the corner of my eye with a tissue, and resolve to speak my truth. I am confident, I say to myself. I am perfectly made. I am intersectional, but my existence is not a box-checking exercise. I did not sneak into Science. I earned my way in and I earned my way up the ranks. I inhale deeply. “Boozled, they know,” I say.

I pause to let you take this in. “They know we’re right.” For a moment, my words hang in the air, as we both come to terms with the enormity of it.

“They know. They know … so … they must be censoring us.”

“They’re all in on it.”

“Our rights have been violated.”

“It’s bigger than Stalin.”

“Bigger than Hitler.”

“It’s the greatest crime of the century.”

We can’t quite get our minds around it. But there was the evidence, right before us! All those blasted, bean-counting Gamma-plusses with their management school jargon, like robots—“sample size, trial registration, publication bias, confounding variables, randomization, observer-blinding, placebo-controlling, effect size, confirmation bias, population variance, regression fallacy, p < 0.05, data collection”—why? Why torture us with this when we did the Science!

“All that stuff is voodoo nonsense!” you say, slamming your fist on the table. “Who cares about a sample size, for the love of God! People are dying!”

“We never needed this back in the 19th century, when researchers like us just went by their gut and their hearts and their brawn and their hormones and their clinical experience and life expectancy was 40 years for males and 42 years for females—”

“They’re all in on the hoax,” you whisper hoarsely, overwhelmed by the sheer evil of it all.

“Every single healthcare professional in America is in on it.”

“They’re all liars.”

“Just like our Science showed!”

“But why?” I ask.

Our hearts race as we try to think it through. Why? Why? Suddenly, you stand up and roar, “I know! I know why!”

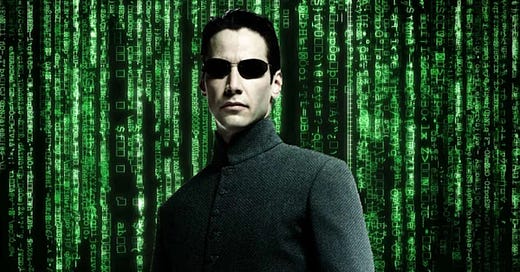

I look at you. A vein is throbbing in your temples. You sit back down in the big leather chair. Something about you has changed. You put on your sunglasses, even though we’re indoors. You say, “You are living is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you to the truth.”

I see myself reflected in your glasses. I look pretty good, I must say. “You take the blue pill,” you continue, “and the story ends. You believe whatever you want to believe.” I keep looking in your glasses, wondering if I should maybe touch up my lip gloss. “You take the red pill. You stay in Wonderland .. and I show you how deep this rabbit hole goes.”

I meet your eyes. I reach for the red pill, pour myself a glass of water, and swallow it in one gulp. I get woozy right away. “Follow me,” you say. You walk into the bathroom.

“Why are we in my bathroom?”

You yank open the door to the medicine cabinet with such force you tear it off the latch and the whole thing clatters to the floor. “Do you get it now?” You point at the floor. I’m confused. Tylenol, Bactrim, band-aids, Clearasil, antacids, six antidepressants; two anxiolytics, and an antipsychotic that my psychiatrist prescribed off-label for me for when I get a little manic. “Do you see?”

I don’t, but I don’t want to admit it. I look again. Could it be that half-empty tube of yeast infection cream? The sleeping pills—what are they again? I usually just call them the Velvet Hammer.

He explodes. “Because They make so much money selling you healthcare.”

I gulp. “Whoa.”

“If you knew all healthcare professionals were liars, you’d never see a healthcare professional again!”

The Red Pill is coursing through my blood, making my mind race. I feel like I’m having a hot flash and taking an ice cold shower at once and my mind is clearer than it’s ever been before, but that’s maybe not a huge advertisement—“And that would mean,” I pant, “that would mean no one would diagnose you with a disease, which would mean—

“You’d always be healthy.”

“Oh. My. God.”

It sinks in. We stare at each other. We have to find a way to tell the world, no matter what They do to us.

We decide to start our own medical journal. But first, I call Joe Rogan.

The trade secrets of your elite overlords

Let me share a secret. If you grasped the problem with our experiment, you don’t need to figure out who the real experts are. You basically have the tools you need to look at the evidence yourself and draw the appropriate conclusions.

You can do this.

The bad news is that YouTube won’t serve it to you in a digestible three-minute videos while they flash ads in front of your face and you’re going to have to do some disagreeable work. But truly, there are no huge insuperable intellectual obstacles to sorting this out. It’s just boring, that’s all.

Stick with me. I’ll show you how.

Google for Smart People

Here’s your first stop. Some of you knew about that already. For those of you who didn’t, yes, you’ve understood correctly—this whole time, there’s been a parallel Google. An alternate Google universe. But this one’s just for the Front Row Kids.

You can use Smart People Google to do your own meta-analysis—the highest quality of medicine there is. Here’s how you do a meta-analysis. You enter a search term like Covid19 vaccine safety and efficacy, or ivermectin to treat Covid19. Then you read the first thirty pages of results.

No, not one result. That’s cheating. No, not just the abstracts, either. You actually read, just like people used to do in the olden days. One page after another. You keep reading until there are no more articles to read, or for three full days, whichever comes last. You can take a break to sleep. As you read, apply the same standards to this research that our editors pretended to apply, above, although of course they were just faking it because they’re in on the plot with Big Healthcare.

But here’s where to apply your suspicion of healthcare professionals. Because you can’t be too skeptical. Well, yes, you can. But you know what I mean. Alas, many of these studies are about as well conducted as our research into the veracity of healthcare professionals. Exactly the same mistakes, too. I’m not kidding you. Really.

There’s a lot of healthcare chicanery out there, I’m afraid. Or just desperate doctors trying to figure out anything that might save patients’ lives during a pandemic and putting this stuff up there because maybe it will help someone.

So ask yourself: What am I reading? Is this a letter to the editor, or are these the results of a properly-conducted trial? Did this work in mice? A computer simulation? A person? People?

Is the hypothesis they’re testing plausible? Are they testing a theory that just doesn’t make sense in light of what we know about medicine? (This doesn’t mean it’s wrong. Just means the results better not be a fluke.)

Are they measuring the right thing? Could they be confusing the effect of one drug with another? Or confusing the effect of being part of a certain group with the drug? How’d they make sure they weren’t confused—did they explain that clearly in whatever they published?

How did they choose the people they were going to study? Are they comparing like to like, group-wise? How big was the study? How big was the effect? How long did the study continue? Did the researchers know who was getting the drug? Did the patients? Are other researchers who are doing similar research getting similar results? Does the result pass the smell test? Does the result even make mathematical sense? (Check their numbers, even the arithmetic. Usually it’s right, but … not always.)

Look at the journal, too. Anyone ever heard of it? Who owns it? How long has it been around? Is it a preprint? Was it peer-reviewed? (Peer-review isn’t magic. A lot of times, I suspect the peers never read these things. But at least it’s one more chance for someone to catch a completely ridiculous mistake—or major fraud—before it’s published. There are incentives to catch those mistakes, too, because sometimes your peers can get rid of you that way and make their way faster to the Valhalla of the grant trough.)

Has anyone written to the editors about the article since they published it? If they have, are they writing to denounce the authors as dangerous frauds? Are they making a decent case?

Take notes. Don’t just look for evidence for your hypothesis. Look for high quality, replicated evidence—a lot of it. The more high quality evidence you can find in favor of the hypothesis, the more likely it is to be “the best-informed perspective the world of medicine has to offer you—as of today.”

This view could change tomorrow, if more evidence came in.

Come back after doing that. Tell me the correct answers to the question.

Believe me: If you didn’t cheat, you’ll know the answers.

How to think about risk during a pandemic

Here’s a second filter. When we consider the risks of vaccines, or any other treatment, we can’t compare adverse effects to the baseline incidence of disease or other adverse medical events that we saw pre-pandemic in a demographically similar population. We have to compare the risks to the new, pandemic baseline.

Let’s spell this out. Suppose that prior to the outbreak of a pandemic, adverse effect x—call it AEx—typically occurs in 1 percent of a demographic group y over a time period z.

Suddenly, a pandemic—a new disease, to which the human population is immunologically naive—breaks out. We develop a vaccine against it. For the sake of argument—just to make things mathematically simple by dealing in round numbers—say the vaccine confers 100 percent protection against the disease. After giving group y the vaccine over time z, we find that AEx has occurred in 5 percent this group.

Do we say, “My God! That’s terrible! Usually only 1 percent of the population gets AEx! This vaccine is dangerous! Take it off the market!”

No. We have to ask, “Okay, but what is the risk of AEx if you catch this new disease? And what is your risk of catching the disease?”

If it turns out that your risk of AEx if you catch the disease is, say, 50 percent, and your risk of catching the disease is also 50 percent, your risk of AEx is, obviously, vastly lower if you’re vaccinated—even if, absent the outbreak of this disease, it would be higher if you were vaccinated.

If the risks of the disease also include adverse effects w, y, and z, this becomes even easier. The vaccination is safe as houses compared to the alternative in this universe. In a universe where the infectious disease didn’t exist, it would of course be insane to take a drug with a 5 percent risk of AEx. But if the disease exists, the only rational way evaluate the risk is in the context of the new baseline.

Obviously, Covid19 really exists. No matter how much we wish it didn’t, we cannot wish it away.

Let’s take a specific example. Rare blood-clotting disorders have been tentatively linked to the AstraZeneca vaccine. I say, “tentatively,” because the numbers are tiny. As of March 16, some two million people in the EU and EEA had received the vaccine; of these, five people below the age of 50—yes, just five out of millions—developed disseminated intravascular coagulation, or blood clots in multiple blood vessels, within 14 days of receiving the vaccine. Compared to pre-Covid figures, this was above the baseline, although note: The numbers are so small that it’s impossible to be sure this was actually linked to the vaccine; sometimes incidents like this—by chance—form clusters.3

This point is important because disease clusters are a well-known and much-studied phenomenon. The number of genuine cancer clusters, for example, is much lower than the number of suspected cancer clusters. Clusters can occur by chance in a random distribution; it’s normal for some areas to have lower cancer rates than expected and some to have higher rates. People often see patterns in events that are in fact random. They’re particularly prone to do so if they have more than one relative, neighbor, or colleague with cancer.

We would typically expect one person to have developed disseminated intravascular coagulation during this period. Instead, there were five. This caused regulators and the media, around the world, to go bananas.

“Alarm! DANGER! AstraZeneca vaccine causes blood clots!”

This was absurd, and dangerously so, and people surely died because of it. What people failed to grasp is that 20 percent of Covid19 patients develop blood clots. If you’re infected with Covid19, the odds developing this kind of rare blood clot—disseminated intravascular coagulation—are forty times higher than the odds of developing the condition subsequent to vaccination.

What are the odds of being infected with Covid19? We don’t know, but since one in three Americans have already been infected, it’s fair to guess they’re at least one in three. I’d reckon that over a lifetime, if you’re not vaccinated, it would be somewhere between 50 and 100 percent—unless everyone around you is vaccinated.

This cognitive trap may seem obvious now that I’ve spelled it out, but I see it bollixing people up all over the Internet. Once you have a Covid19 pandemic, there is nothing you can do to reduce your risk of disseminated intravascular coagulation back to the original baseline. Nor, for that matter, your risk of myocarditis—nor your child’s. “Normal level of risk” is not an option on the menu. The only conceivable way you could return to your baseline risk—save hermetically sealing yourself off from the rest of the human population—would be to be the only person who doesn’t get vaccinated when all your fellow citizens do. Even if you could make that happen, it would plainly be immoral to do so.

To reject the vaccine because of the risk of serious side effects without considering the risk of acquiring Covid19—and with it not just the risk of that side effect but of many far more serious ones—isn’t even adjacent to a rational scheme of thought. Yet I hear one person after another expressing this very sentiment. I suspect the error reflects a longing we all feel strongly. This is not normal. I hate this pandemic. I wish there were no pandemic.

None of us want to accept that no matter what we do, our life expectancies have been shortened. But they have been. You’re getting the pandemic risk whether you want it or not. No one gave you a choice. It’s unfair, and it’s a gross violation of your right to life and your bodily integrity and all the things anti-vaxxers say the vaccine would be—except you’re arguing with a virus, which is only arguably alive, no less sentient. The only choice you get in the matter is whether you want a massive risk to your life and health or a small one.

You don’t get to check the box marked “None.” Argue with God, not me.

Yes, Claire, but what if there’s actually a miracle drug that will cure you if you get sick, and which completely protect you from Covid19 and has no risks?

Wouldn’t it be comforting to think so? Yeah, that’s the first reason your intuition on this is suspect. But I’ll let you work this out as homework: Start reading your clinical trials. Read twenty for each proposition. See for yourself.

Too much, you say? No, actually, it’s not. I did it. You can do it, too. No, it wasn’t fun for me, either. If you don’t know what something means, look it up. Unless you want to play Expert Roulette—without having any clue which one is right—this is your only choice.

Tomorrow, we’ll cover a few more topics that will help you as you read. The placebo effect. What reports in VAERS really mean. Whether there’s a giant conspiracy to prevent people from doing proper studies of ivermectin so that Big Healthcare can sell you vaccines. What to think about Dr. Quack’s fish guy, his carpet cleaner, and his house cleaner, who all got sick after being vaccinated. Whether the spike protein “toxic.” Whether it’s “cytotoxic.” Whether it breaks off and flies on a broomstick into your ovaries, making you infertile.

If you have any more questions, don’t ask me. Why would you? I’m not a doctor, I’m the co-editor of the Cosmopolitan Globalist. Just keep reading—but do it on Smart People Google. And stay the hell away from social media.

Because that really is a conspiracy. It’s a conspiracy so diabolical and ingenious that even though you know it’s true, you still can’t believe it could work that way or that they could be pulling it off. It’s a conspiracy that’s made the Titans of Big Tech wealthier than the rest of the world put together by making you stupider and stupider and angrier and angrier—all while somehow getting you to give them the smack they use to addict all the rest of the lab rats, while they create nothing but the algorithms that are making you so berserk that you could even manage to convince yourself Big Tech is conspiring behind the scenes to screw you over, never mind that they’re doing it right in front of your eyes, and with your eager cooperation. Meanwhile, you keep clicking, clicking, clicking, clicking, and clicking, jonesing for another pipe of the uncut information smack, and you’ll be damned if you’ll ever let them vaccinate you, because you’ve taken the Red Pill, and you have done the Science, and you have seen the videos from the Qualified Medical Doctors, and so you will never allow them put a microchip in your arm, track your every move, and turn you into a slave.

Pasiphae was a mythological half-cow, half-human beast.

Claire Lehmann has joined the Cosmopolitan Globalists in our quest to rectify the thought of the anti-vaccination left deviants, wreckers, and saboteurs. A brief article I’ve written with Yuri Deigan summarizing the case for vaccination and against excessive ivermectin enthusiasms will appear this week in Quillette. If you’re short on time and all you want is advice from an expert you can trust, skip this and go straight to that article. (I don’t happen to be an expert in any medical discipline or subdiscipline, mind you. But you can trust me.)

See, e.g., Understanding cancer clusters. This is obviously a meatball statistic; I’m pulling it out of thin air. The real statistic would depend entirely on things we can’t possibly predict—the level of vaccine uptake, people’s behavior, the way the virus mutates. But to say it’s “higher than one in three” seems reasonable, since this is what we’ve seen already, under conditions of extreme social distancing. Vaccination and prior infection will put the brakes on future outbreaks, but it seems likely Covid19 will be with us for generations. If you keep taking the risk of exposure, year in, year out, the odds won’t be on your side. The odds of dying from it, of course, will grow as you age.

Claire, you are uncommonly brave for continuing to dissect this (waves hands around in the air) in such a logical and rational manner. Thank you.

Here in Switzerland, my head exploded again yesterday at this front-page headline in the "NZZ am Sonntag" (initially welcomed as a Sunday dose of the excellent Neue Zürcher Zeitung, but sadly gone the way of the Sunday tabloid): "Not many teenagers want to get vaccinated against Corona" with the helpful subhead pointing out "Less than 10% of 12- to 15-year-olds have registered for a vaccination so far."

Well. The federal authorities approved the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine for the 12-15 age group on June 4. The Moderna vaccine is not approved for under-16. These are the two vaccines in use in Switzerland (A third, Johnson&Johnson, was approved, but Switzerland didn't order or buy any of that one.) It was another 10 days to two weeks before the cantons managed to update their registration platforms to allow people under 16 to be registered. I know this because I live with a 14-year-old who is at least impatient as I am.

Nowhere in this piece of hard-hitting journalism is it mentioned that 12- to 15-year-olds are highly unlikely to register themselves for a vaccine appointment. Since when do 12- to 15-year-olds act autonomously and take their own decisions? Not even in this direct democratic paradise of individual responsibility is that possible. The selected vaccine centers are not easy to reach, and several cantons explicitly require under-16s to have written permission from a parent or guardian. No, it is instead posited that those young folk don't find it necessary since infection numbers are low and restrictions are being relaxed.

Sigh. It's the parents. They are too busy to bother, since it's now summer vacation and the kids have to be kept busy somehow. Or, see above, numbers are low, etc. Or– another wild theory put forth by the so-called NZZaS journalist– it's not clear whether the federal government really recommends the vaccine for all 12-15s or only those with a chronic illness. Or, what I most fear, the response I have heard from many (vaccinated) friends and acquaintances: "No way am I letting my child get that stuff injected!"

It's all so tiresome, and tiring. Frankly I am more worried about the potential effects of Long Covid than the potential long-term side effects of a vaccine. My 14-year-old is, physically, closer to adulthood than childhood. Why would you not want to afford your child the same protection that you have? And why is the allegedly "liberal intellectual" media in German-speaking Switzerland writing such rubbish? (yes, I've asked, and wait eagerly for a reply)

I registered the manboy in two cantons, since we live on a border, and apparently a new shipment of Pfizer dropped last weekend because we were offered appointments in both venues. He's getting his first shot tomorrow and is relieved that he is catching up with his American cousins. Whom we will be able to visit again one day, maybe soon.

Another excellent piece. I would love to hear you debate Dennis Prager, and I hope you will be back on Uncommon Knowledge again to discuss these important issues. Some people, of course, are immune to the effects of logic, but your reasoned approach no doubt has and will continue to save lives as we move forward. Thank you.