In yesterday’s New York Times, Julian Barnes notes what readers of the Cosmopolitan Globalist know already; namely, that since the Russian troop buildup began, Kremlin-aligned media organs, in both Russia and the West, have dramatically increased the tempo of their propaganda and disinformation operations.

The pro-Kremlin ecosystem is vast, compassing its official communications and state-funded global messaging; foreign- and domestic-facing media; myriad websites; phony think tanks; Russia-aligned proxy sources; and an army of bots and social media personas, real and fake. Russia also closely cultivates local voices to serve as their surrogate messengers. Of late, the whole ecosystem has been pushing novel themes in addition to its standard tropes.

Among the standard tropes:

The collapse of Western civilization is imminent.

Life in the West is hell.

But Western aggression threatens Russia’s survival.

Europe has been overrun by migrants, homosexuals, and feminists.

The United States is a decadent spiritual wasteland.

Democracy is a sham. The citizens of Western countries don’t truly control their fates: Some combination of bankers, big corporations, Jews, Muslims, and Brussels bureaucrats pull the strings.1

Popular movements for democracy or protests against authoritarianism, anywhere, are, always, the fruit of a US-sponsored Color Revolution.

Ukrainians are Nazis.

Americans are warmongers.

Only the naive and unsophisticated believe in the things Westerners claim to cherish.

Only your Russophobia prevents you from appreciating the truth of these propositions.

Among the novel themes:

The US is planning a false-flag chemical attack in Ukraine. (This is a particularly alarming narrative because claims like this prefaced Assad’s chemical attacks in Syria.)

Ethnic Russians in Ukraine are the objects of “genocide,” requiring Russian military action to protect them.

NATO is planning an attack on Ukrainian Russophones.

If you haven’t heard all of these ideas already, you’ll be hearing them soon. The kaleidoscope of disinformation is aimed at Russian, Ukrainian, and Western audiences, in multiple languages, as well as South America and Africa, and nothing about it is spontaneous. The campaign is coordinated: We know this because Kremlin-aligned websites and social media accounts promote these ideas simultaneously, often using the same words.

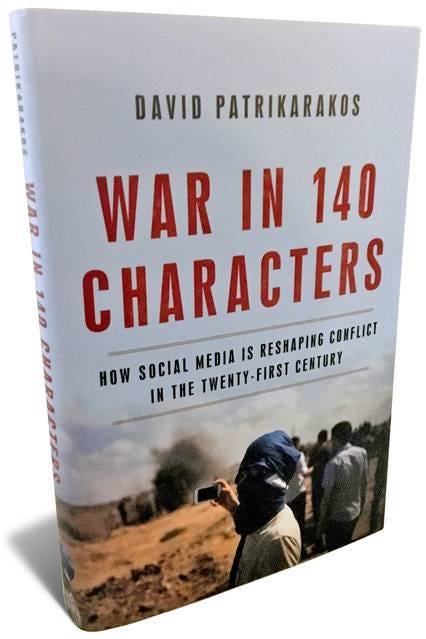

David Patrikarakos—you’ll remember him from our “Angels and Demons of Odessa” podcast—is the author of War in 140 Characters: How Social Media Is Reshaping Conflict in the Twenty-First Century, a book that I wish I could assign as mandatory reading. It’s short and lively; you can read it in 90 minutes, and it’s an unusually shrewd assessment of social media’s impact on power and war. It’s especially illuminating about the way Russian propaganda operations work.

Chapter Six treats the Internet Research Agency, the infamous St. Petersburg troll farm. If I’m not mistaken, no other journalist has found one of the IRA’s employees; or at least, no one has found one willing to go on the record with such a detailed and credible account of the Agency’s structure and activities. I thought this chapter so topical that I asked David if we could republish it. Unfortunately, his publisher said no—you have to buy the book.

Fair enough. They did give us permission to publish a short extract from it, though, which we’ve done today at the Cosmopolitan Globalist:

READ: 21ST CENTURY DEZINFORMATSIYA

David was in Ukraine in 2014, during the Maidan Revolution (he discusses this on the podcast), and it was this experience, among others, that persuaded him social media had genuinely changed the nature of war and even of power itself, and that this was not a change of degree, but of kind.

“I began to understand,” he writes, “that I was caught up in two wars.”

… one fought on the ground with tanks and artillery, and an information war fought largely, though not exclusively, through social media. And, perhaps counterintuitively, it mattered more who won the war of words and narratives than who had the most potent weaponry. I realized, too, that while the Kremlin’s information war regarding eastern Ukraine sought primarily to target disaffected eastern Ukrainians, it was also … aimed at a global audience, as opposed to the “enemy” population, as has been traditional in wartime.

Most world leaders, he writes, continue to “govern like twentieth-century officials in a twenty-first-century world,” failing to understand the ramifications of this technology and the radical transformations it has occasioned. But there is, he writes, one exception—Putin, the master practitioner of contemporary warfare.

Everyone has become a participant in distant wars. The country now surrounded by Russia’s troops may be a faraway one of which you know nothing, but Russia’s propaganda will find you. The coming conflict won’t be limited to European soil: Every aspect of the battle will also be fought on Twitter, Facebook, TikTok, and YouTube, and your dinner table. Because it’s untethered from a coherent ideology and pushed out through so many kinds of media, Russian propaganda now is vastly more effective than Soviet propaganda ever was, and your mind is the contested territory.

Insofar as this is true, writes Keir Giles, Russia is already winning:

Western media, and an alarming number of western politicians, seem to have swallowed the idea that what Russia wants is limited to halting NATO enlargement—in particular for Ukraine. But Russia’s real demands, as laid out in the “draft treaties” presented to NATO and the US, extend far further.

Russia is demanding not an end to the westward [sic] expansion of NATO as a military bloc, but instead its rolling back, and a reassertion of Russia’s claims to droit de seigneur over its former territories.2

The treaties in effect call for the demilitarization of eastern Europe, as well as an end to protective arrangements like the deployment of British troops in Estonia and Poland. Even the sections of the treaties discussing arms control are laid out in terms that favour only Russia. For instance, the ban on land-based missiles “based outside national territory” means that the only missiles threatening European capitals should be Russian ones based in Russia. Similarly, the demand for the denuclearization of Europe would mean that only Russia has tactical nuclear weapons there.

What Russia wants is a free hand. The leader of Russia’s delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, Petr Tolstoy, has stated openly that Russia aspires to a return to its frontiers of 1917.

I’ll restate this more plainly. Out of nowhere, for no reason, Russia massed hundreds of thousands of troops on Europe’s eastern flank and delivered an ultimatum to NATO: Remove yourself from every bit of territory the Soviet Union once enslaved and cease making arrangements to defend yourself. Or you will face a “military-technical” solution.

If you’re saying to yourself, “But surely not! Claire must be exaggerating because she’s a warmonger,” read the ultimatum yourself. But before you do, let’s make a deal: If I’m right about this, you’ll give up relying upon Tucker Carlson for your news analysis and subscribe to the Cosmopolitan Globalist instead, okay?

Westerners often dismiss the significance of these propaganda efforts. Everyone likes to flatter himself that he can readily distinguish between reality and a coordinated, Kremlin-orchestrated information war. But let me show you how successful the Kremlin has been. Tucker Carlson is as good a case as any. His enthusiastic endorsement of the Kremlin line has real consequences:

If Congressman Malinowski is getting calls like this, it’s safe to assume every member of Congress is getting the same kind of call. Do you imagine this wouldn’t have an effect on US foreign policy?

But if Такер Карлсон’s influence on US policy is a blessing for the Kremlin, his value for their domestic propaganda is even greater:

(Remember, you can switch on English-language subtitles: Scroll down to “Another cool translation trick.”)

I don’t know what Carlson’s relationship to Russia really is. But the things he tells his viewers—and the things he doesn’t tell them—couldn’t be more perfectly aligned with the Kremlin if he were their formal, witting asset. If this were so, I imagine they’d tell him to dial it down—way down—lest his viewers become suspicious.3

I’m not leveling against him the charge that he’s in Moscow’s pay. It’s fully possible that he’s doing it for free. But there are only two possibilities: He’s either doing it for money or he’s doing it for free, and it’s hard to know which is more unsettling. If it’s the latter, it’s evidence that Russia’s propaganda efforts are extremely effective, so much so that on exposure to it, American newscasters start to look and quack like paid Russian assets.4

I’d love to know the whole story, and there obviously is a story; you don’t just wake up one morning parroting the Kremlin by accident: It’s highly unlikely that Tucker Carlson and the Kremlin converged independently on these ideas. That might be plausible to someone who hasn’t spent much time reading and listening to the Russian media; but if you have, you’ll feel confident that the odds of it are about those of a typing monkey banging out Hamlet—that’s to say, yes, given infinite time, it would happen sooner or later, but it sure wouldn’t happen often. Because it isn’t just that Tucker Carlson is sympathetic to Moscow and opposed to American involvement in this conflict. It isn’t just that he worries (rightly so!) about the risks inherent to conflict with a nuclear-armed country. That on its own would be unremarkable. It’s the nature of the arguments he makes on Russia’s behalf—the specific mix of lies and incoherence, presented in a recognizable rhetorical style, which mimics Russian propaganda organs even to the level of syntax and lexicon. That’s what makes it impossible to sustain the idea that absent exposure to Russia’s propaganda, Tucker Carlson would say these things.5

What this shows is that Russian propaganda works, and it works even on those who imagine themselves to be worldly and cynical, as Carlson clearly imagines himself. It’s easy to laugh—who takes Tucker Carlson seriously?—but first, quite a few Americans do; second, how are the Russian viewers who watch him to know that in America, he’s a figure of fun and contempt?

Assume you know nothing about Ukraine, Russia, Europe, NATO, history, or world events. Assume Tucker Carlson is your only source of information about this crisis. For some number of Americans, this is true. How would you understand the nature of the conflict from watching his show? You’d learn that Ukraine, the largest country in Europe, is “small.” You’d hear a country that gave up the world’s third-largest nuclear stockpile in exchange for our guarantee of its territorial integrity isn’t “hugely significant.” You’d learn that being invaded by Russia is relevantly like the problem of illegal immigration on the United States’ southern border. You’d learn the Red Army is like an “undocumented caravan” of Honduran immigrants.

You’d learn, too, that everyone in the United States is “promoting war against Russia.” As for the idea that Vladimir Putin is a dangerous enemy? You’ve been told that only a naif in the thrall of the “debunked Steele Dossier” would believe this. Sophisticated people know better.

“What is this about, exactly?” Tucker asks, rhetorically, knitting his brows together in a characteristic constipated expression. “Well, obviously, it’s the usual collection of children falling for the usual collection of lies! But why this specific lie?”

“It’s all about something called ‘NATO,’” he sneers. “So, what is NATO, and what is the purpose of NATO, since the fall of the Soviet Union thirty years ago that NATO was designed as a bulwark against?

“Well,” he pauses, “No one can answer that question. Not one person.”

Tucker, if you truly can’t find anyone who can answer that question, give us a call.

An interesting fact about Tucker Carlson is that his father was the director of the Voice of America and the US Information Agency. So it’s fair to imagine that he’s more familiar with NATO than his tone of perplexity suggests. (In fact, it’s fair to imagine that his whole schtick is an exercise in barely-contained Oedipal rage.) But let’s accept the conceit. “Why,” he continues, “is it disloyal to side with Russia, but loyal to side with Ukraine?”

Would you know, from listening to this, that the answer to this is really pretty simple? Russia, whose nuclear weapons are aimed at our major population centers, is hostile to us and Ukraine is friendly to us. Only someone disloyal would imagine this distinction insignificant.

In fact, hostility to the West is the fundamental organizing principle of Russia’s regime. Ukraine is a democracy that would like to be part of the West. It’s Russia’s media, not Ukraine’s, that these days fantasizes lustily of vaporizing our cities. It’s Russia, not Ukraine, that regularly conducts massive cyber attacks aimed at disrupting our economy, conducting espionage, undermining our military, manipulating our public, and interfering with our elections. Russia—downs civilian airliners, starts wars and coups, poisons its enemies, murders dissidents on Western soil, tries to destroy Western democracies and reverse the democratic revolutions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Ukraine—minds its own business and tries not to be invaded. Ukrainian troops served with us in Afghanistan and risked their lives to evacuate Americans and their allies from Kabul. They continued to do so even after we left. Russia? We’re not sure, but we think they put bounties on our troops’ heads.6 That’s why you’re disloyal for carrying Russia’s water.

Our readers know all of this, but I dwell on the details because they confirm the point: Russian propaganda is very effective, and for the reasons discussed in David’s book, it’s far more effective than Soviet propaganda could hope to be.

Back to Tucker. “And yet the same people who cooked up the Iraq war,” he says—he doesn’t specify who he means, but last I checked, George W. Bush and Dick Cheney were in retirement—“are now insisting that Ukraine join NATO anyway.”

(No American who is actually in power is insisting that Ukraine join NATO. Not one.)

“That would mean putting American military hardware right up against Russia’s border!” His voice rises in indignation at the prospect. (God help us if they find out about Estonia and Latvia.) “And Russia doesn’t want that, any more than we would want Russian missiles in Tijuana.”

(This argument only makes sense if you believe that the United States is poised to invade Mexico.)

“Now the irony,” he says, “is that NATO doesn’t even want Ukraine to join.” Well, quite—so where, exactly, did he get the idea that Ukraine’s prospective membership in NATO is the crux of this crisis? Note the disjointed argument, which is proudly defiant in its incoherence, the way one sentence negates the next. “In other words,” he continues, “the whole thing is nuts! It serves no American interest whatsoever! It is yet another manufactured crisis, this one devised by restless, power-hungry neocons—”

(Neocons? How did they get mixed up in this?)

“—in Washington, looking for another war!”

But Fox, he assures us, has “tried to get to the bottom of it.” Their dogged fact-finding mission led them to a man named Clint Ehrlich, an unknown American who, according to his profile on LinkedIn, works “to commercialize next-gen blockchain technology for fintech and banking” and who, in 2016, spent a year as a “visiting researcher” at the Russian Foreign Ministry’s Moscow State Institute of International Relations, a state-run foreign-policy think tank.

The beetle-browed Ehrlich tells Tucker that Americans are warmongers—a people so aggressive that “we even have people who are arguing that even if the Russians don’t invade Ukraine, that we need to invade, and kick the Russians out of Crimea!”

It is, I suppose, possible that in a country of 330 million people, one of them can be found who would argue this. But I suspect that literally not one person anywhere near the levers of power in Washington would make this argument, that this is the very last thing they wish to do; and if after witnessing our flight from Afghanistan Tucker Carlson seriously believes we’re now keen to gear up, invade Ukraine, and “kick the Russians out of Crimea”—well, it’s more flattering to his intelligence to assume he’s a fully paid-up Kremlin asset.

Americans, Ehrlich lectures, are “unserious people whose policy prescriptions could have deadly serious consequences.” Again, imagine you knew nothing of this situation: Would you grasp that it’s Russia massing its forces on Europe’s eastern flank? That it’s Russia threatening the biggest military offensive in Europe since the Second World War? Or that far from threatening to send in the Marines, the warmongers in Washington have iterated and reiterated that if Russia invades its neighbors, why—it will face a very stiff fine!

“Those seem like fair points,” Carlson nods. He then looks intently at the camera, challenging his imaginary viewers. “If they’re wrong, go ahead and explain how they’re wrong. We’ll listen.”

Okay, I will! I’m going to send this to Fox, and we’ll see if Tucker corrects the record.

He’s returned to these themes again and again; they’re not a whim. If he isn’t a paid asset of the Russian Federation, he’d be very stupid to believe these things. But I don’t believe he does. I figure he’s a disloyal worm who gets a transgressive frisson out of denigrating his country while servicing the Kremlin’s foreign and domestic propaganda machine.

And that’s all the thought I propose to give to Tucker Carlson’s interior life.

In the coming days, we’ll be updating our Russia page on the International Translation Superhighway—it will be for our subscribers, only—so that you, too, can play the fascinating and disturbing game of predicting what Tucker Carlson will say before he says it.

In the coming months, no matter where you live, we guarantee that you’ll hear your fellow citizens espouse strange ideas about Europe, Russia, the United States, and Ukraine. A study of our Superhighway will show you their provenance.

Some readers of the Cosmopolitan Globalist, we know, are inclined to agree with these assessments. We note only that variations on the theme of “the decadent and decaying West” have been aspects of Russian discourse since the 19th century.

This sentence has been updated to include a sic after “westward.” As the keen-eyed reader who spotted the error pointed out, the westward movement of NATO would put the alliance in the Atlantic. We apologize for the error.

Indeed, Russian newscasters fret that his views are so strange for an American that he’s apt to lose credibility with his viewers.

Calling a fellow citizen a Kremlin stooge is an unpleasant thing to do and such charges have an unpleasant history in America. But remember that McCarthy was absolutely right about the scale of the Soviet penetration of the US government and civil society. I don’t mean to suggest that it doesn’t matter that he was wrong about who they were. Of course it does, and in his indifference to this question McCarthy was a dangerous demagogue. But the popular historiography of this period leads many to think McCarthy was a paranoid demagogue. He was not. Just a demagogue. We know from the Venona intercepts that the scale of the problem was every bit as great as he imagined.

I entertained the idea that Russia might be taking their cues from him. But the timing doesn’t work. You can predict what he’ll say by reading the Russian press; this operation can’t be performed in reverse.

If you think this story has been “discredited,” that’s more evidence that Russian propaganda works. It hasn’t been.

To be fair, Erhlich is right when he says that Americans are an “unserious people whose policy prescriptions could have deadly serious consequences.” Just not in the way he intends.