A dispatch from Tbilisi

The 2008 invasion of Georgia was a dress rehearsal for the invasion of Ukraine. John Oxley reports from a city that's fed up with accommodating Putin.

John Oxley, Tbilisi

The dogs are the first thing you notice in Tbilisi’s Sololaki district. Stray Caucasian Shepherds, tagged to show they have been neutered and vaccinated, wander among the crumbling Italianate courtyards of the nineteenth-century bohemian homes, begging for scraps among the wine bars and restaurants that cater to the city’s cool crowd.

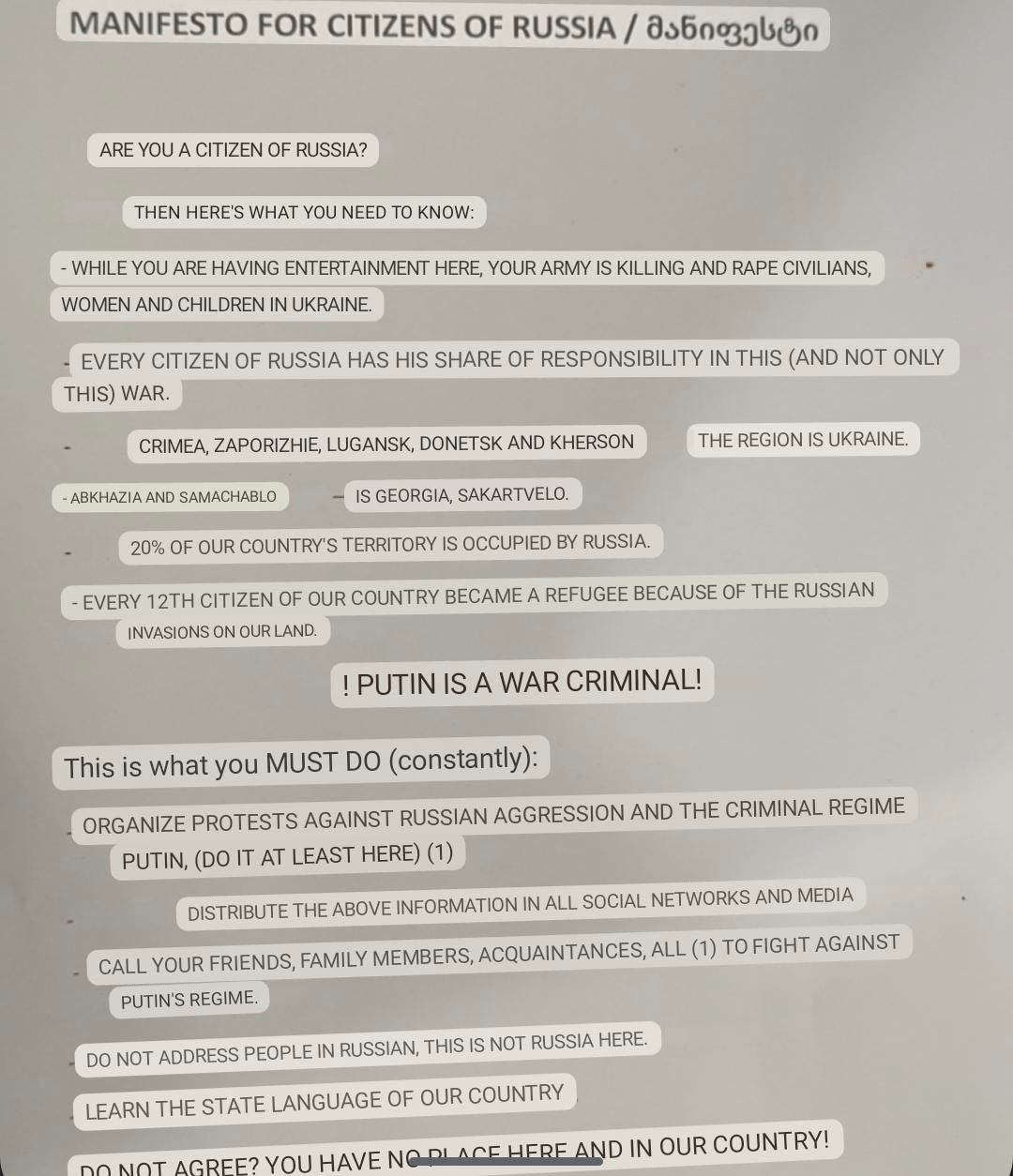

The second thing you register is the graffiti. Almost every wall is marked with a symbol of resistance to Russia. There are Ukrainian tridents. There are collages of EU, Ukrainian, and Georgian flags. Or simply, “Fuck Ruzzia” in big red letters. These messages are aimed at Georgia’s government, but also the hundred thousand or more Russians who have fled sanctions and mobilization to come to the city.

The capital’s hippest bars have taken to displaying manifestos on their doors: Russians who wish to enter must accept responsibility for Russia’s aggression in both Georgia and Ukraine.

Soviet efforts to suppress the Georgian language are remembered bitterly here: Staff tell them curtly that only Georgian and English are spoken and orders won’t be taken in Russian. Businesses display EU flags in their windows to signify that they don’t approve of the pragmatic courtship of China and Russia: They aspire to democracy and freedom.

If at first Georgians are hesitant to talk about politics with a stranger, after a few glasses of deep red wine and chacha—the grape-pomace brandy for which Georgia is famous—the stories begin to flow, and they reveal the depth of the antipathy toward Russia. The memories of the 2008 invasion remain vivid. Georgians fear more border incursions, or another outright invasion. They are all too aware of the crimes Russia has perpetrated in Ukraine. (Nor do they hesitate to tell visiting Russians that they’re aware of them.) Some rail at the “arrogance” of the Russian émigrés who treat Georgia as if it were an imperial outpost, displaying no contrition for the historic and recent humiliations Russia has imposed on Georgia.

There is a pervasive awareness here of Georgia’s precarious position. Like Ukraine, some 20 percent of it is territory is occupied by Russia. Unlike Ukraine, Georgia has no plan to oust Putin’s troops, nor support in doing so. Instead, the government is attempting to navigate a narrow path between Russia and the other world powers. It is a dangerous exercise.

For almost all of recorded history, Georgia has sought to balance its interests against those of more powerful nations, which is why one of the better English-language histories is titled Edge of Empires. Bound by the Black Sea and the Caucasus mountains, tucked between Russia and Turkey, and close enough to Iran to have been repeatedly annexed by the Persian Empire, the name of the country may as well be “Buffer State.” That is indeed what it has largely been for millennia.

Georgia emerged at the edge of antiquity. On the east coast of the Black Sea in what is now western Georgia lay Colchis, a Greek settlement known for its riches. Home to Media and the Golden Fleece, it was said to be the destination of the Argonauts. Pompey mounted incursions into eastern Georgia but failed permanently to conquer it. He instead exacted tribute, setting a precedent that would endure. Georgians have long dealt this way with the various invaders who have pitched up at their borders.

Traveling through Georgia, you see why. It is rugged, fringed with mountains on almost every land border. To the north, the Caucasus stretch up towards Elbrus, the tallest mountain in Europe, just inside Russia. Yellow stone churches perch on cliff tops alongside slender, six- or seven-story defense towers, unique to the region. Between them, in verdant valleys and planes, rows of vines grow around squat wineries with wooden balconies, almost Turkish in appearance, where Georgia’s most famous export ferments in terracotta amphorae.

In the wake of the Romans came one after another empire: The Persians, the Seljuks, the Sassanids, the Ottomans, and more probed the kingdom, claiming territory and extracting concessions. Tamerlane was the first fully to conquer it, but Moscow’s incursion, at the start of the 19th century, began the long period of Russian dominance from which Georgia is still struggling fully to emerge.

In 1800, Georgia was incorporated into the Russian Empire by proclamation; subsequent wars against the Ottomans brought its full territory under Imperial control. The Bolsheviks crushed a bid for independence in the chaos of 1917 and folded the nation into the Soviet Empire. Despite birthing its most powerful despot, Georgia enjoyed few privileges while part of the USSR.

In 1991, Georgians eagerly celebrated independence. But once again, Georgia found itself delicately navigating relations with a far more powerful nation. Though officially expelled, Russia continued to exert a baleful influence in Georgia, backing Abkhaz separatist forces in the 1992–1993 war in Abkhazia. The separatists succeeded in driving Georgian forces from the northwestern region of the country and achieving de facto independence. According to the US State Department, the Abkhaz forces then “moved through captured towns with prepared lists and addresses of ethnic Georgians, plundered and burned homes and executed designated civilians,” and were “credibly reported to have tortured, raped, killed, expelled, and imprisoned hundreds of Georgians and other non-Abkhaz.” Some quarter of a million ethnic Georgians fled, virtually the entire Georgian population. The Kodori Gorge became a death trap for refugees, fleeing on foot, who died of cold and starvation.

In 2008, when NATO promised to consider Georgia’s bid for membership, Russian-backed South Ossetian separatists began shelling Georgian villages. Russia, falsely accusing Georgia of committing “genocide” and “aggression against South Ossetia,” launched a full-scale invasion by land, sea and air. Trading land for peace, Georgia acquiesced to Russia’s occupation of South Ossetia. Again, ethnic Georgians—some 20,000—were forcibly displaced.

For the last decade and a half, an uneasy peace has endured. Though there is no hot war, Georgia’s authority has been neutered; it is only half-sovereign. Russian troops remain in South Ossetia, perhaps an hour’s drive from Tbilisi. The administrative lines around the occupied territories are dangerous, with Russian and separatist forces known to kidnap and detain civilians on the Georgian side of the lines—a low-level, creeping invasion which denies Georgia full control over a growing amount of territory. Russia continues to stoke political instability in Tbilisi while menacing it with the threat of another full-scale invasion, to be executed at the time of Putin’s choosing. Those who suggest Ukraine make the same bargain, take note: The threat is merely stalled, not averted.

Georgia cannot reasonably be expected to oust the occupiers. It lacks the men and materiel to seriously resist any future invasion. It has no room for a strategic retreat. It In Gori, Stalin’s birthplace—a midsize city that was temporarily occupied in 2008—people told me that if the Russians came again they would be under occupation before Tbilisi had time to respond.

The disputed territories remain in limbo. Russia has made gestures toward incorporating them, but there is little local appetite for it. Their push for independence is rooted in the ancient history of the region, where kingdoms were carved out as empires swept through the Caucuses. If they desire separation from Georgia, it is because they wish to be sovereign countries, not forgotten southern Russian oblasts. But their independence is a goal neither Georgia nor Russia are keen to facilitate.

Georgia has endeavored to conciliate the greater powers and reconcile their competing interests. Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, however, this has been harder: The country is pulled in different directions by the EU and China, and by Russia, its neighbor and occupier. Being all things to all parties has become more challenging, especially because popular opinion has shifted even more dramatically against Russia and with it, against the incumbent Georgian Dream party. It feels as though a shift is brewing: The equivocation of the governing party and its reluctance to criticize Moscow enrages Georgians who want them to take a stronger stand.

Georgia remains massively economically entwined with its northern neighbor. After Turkey, Russia is Georgia’s largest trading partner. On the main road north out of Tbilisi, Russian trucks rattle by carrying cross-border trade. The government has refused to join the anti-Russian sanctions regime, citing the threat to its economy. It has provided some humanitarian aid to Ukraine, but no military support.

This might be pragmatic, but Russia has of course cultivated its influence in Tbilisi. The Kremlin has at times praised the country for its accommodating position toward Moscow since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. Georgian Dream’s domestic playbook closely resembles Putin’s, alas, including its imprisonment of former President Mikheil Saakashvili, who is now hospitalized following a hunger strike in prison and a series of illnesses. Georgian Dream’s billionaire founder, Bidzina Ivanishvili, made his fortune in Russia, and the country is awash in rumors about his links to the Kremlin. Certainly, the party has been far more conciliatory to the occupier than many here would like.

Simultaneously, Georgia has sought to play the big economic blocs against each other. After Russia launched its major invasion of Ukraine, Georgia submitted its application to join the EU. It now has “potential candidate” status, a curious position that’s a rung below “official candidate.” It’s far from clear that the EU will be willing to expand into the Caucasus or that Georgia will be able to meet the EU membership criteria. But some integration is in the cards, and the Georgian government is happy to accept funds for EU flag-festooned development in the country.

Balanced against these relationships is Georgia’s association with China. As a land bridge to the Black Sea, Georgia plays a key role in the Belt and Road initiative. Chinese companies are expanding Georgia’s main east-west road, which will connect to the Poti Sea Port, Georgia’s largest.

The Georgian government hopes to secure Georgia’s future, in a new age of empires, by making itself indispensable to everyone. Georgia’s geography, by their logic, will allow it to become the key to East-West trade, which will not only bring economic benefits, but protection from Russia. Yet trading with all the major powers is a dangerous game: Georgia could wind up with a reputation as an unreliable partner, vulnerable to pressure from its trading partners’ rivals and adversaries.

Georgia’s history of poor governance complicates matters. Since independence, the country has failed to generate effective, honest, and popular leaders. The former Soviet administrator Eduard Shevardnadze allowed corruption to metastacize. When he was ousted by the Rose Revolution, Mikheil Saakashvili came to power posing as a Western-facing reformist, and he did curb some of the worst excesses. But he was nonetheless tied to human rights abuses and graft. Now, the country is run by the Georgian Dream party, an ideologically amorphous, oligarch-backed entity; it too has been credibly accused of anti-democratic practices. Earlier this year, the Russian-style laws it proposed to stigmatize foreign-funded NGOs inspired mass protests. Following this, it lost its parliamentary majority.

The Georgian Dream will be tested in next year’s parliamentary elections. It’s unclear what state the coalition will be in by then. It is also unclear who the opposition will be, given Saakashvili is in jail and his United National Movement widely discredited. The polls will probably fail to meet international standards of integrity. After the last election, protests and protracted negotiations followed allegations of rigging from opposition parties.

Georgia’s high-wire act is fraught with the opportunity for miscalculation. It risks winding up loved by no one, trusted by no one, vulnerable to Russia, in hock to China, and too corrupt for the EU. Nonetheless, the West now has the chance to make friends in Tbilisi, and it should.

Georgia’s weakness in 2008 no doubt encouraged Putin to invade Ukraine. But his invasion of Ukraine hardened Georgian sentiments against Russia. The EU and the US should appreciate this and urge Georgia closer. There is a burgeoning appetite here for a freer and more democratic country, one ultimately aligned with the West. It would be foolish to squander that.

When Russia rolled into Ukraine with full force, some argued that it showed the good sense of Georgia’s accommodation. But this is short-sighted. Ukraine has the chance of a military victory that permanently secures its sovereignty, ends the Soviet legacy, builds the Ukrainian nation, and ties it closely to the West. Georgia will struggle to oust Russia from Abkhazia or South Ossetia, or indeed from its own internal politics. It would be more apt to conclude from Georgia’s example that trading land for peace gets you neither.

Read more by Cosmopolitan Globalist favorite John Oxley at Joxley Writes.

Speaking of the Caucuses …

Don’t miss this article by Melik Kaylan, who’s a super-smart analyst: The Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict can change the balance of power in Iran, Turkey, Russia, all the way to China:

A decades-long story about a localized enclave in a deeply isolated zone—how can it have wider ramifications in terms of the global power balance? How can it affect, say, China or Europe or the Mideast? Seems fanciful but what happens between Armenia and Azerbaijan, even specifically the control over mountainous Karabakh, does potentially shift far-flung inter-continental alignments. Only the neighboring countries talk about that—if they choose to. Some don’t because it’s the elephant in the room. This column is not about the historical grievances or human rights outrages of the Karabakh conflict. Those are important but exhaustively covered elsewhere. What you don’t see anywhere is a proper look at the superpower stakes hidden in the geography.

Here’s the key:

If the Turkic bloc begins to gel and act in concert, a new threat emerges to Iran, Russia, China, not to mention Armenia. In China, the Uyghur Turks would feel emboldened. In Russia, numerous Turkic regions from Tatarstan to Buryatia might start seceding. Iran, above all, would feel the threat as the population of its own Azerbaijan province would want to unite with their cousins to the north who have a country of their own. Turkic solidarity is why Turkish President Erdoğan, in the teeth of global criticism, has just visited Baku to congratulate Azerbaijani president Aliyev for his “victory” in Karabakh.

The invasion of Ukraine has ended the post-Soviet era and ushered in the effective end of exclusive Russian dominance in the South Caucasus.

Playing with Fire: Georgia’s cautious rapprochement with Russia. As the war in Ukraine grinds on, the notoriously troubled relationship between Georgia and Russia has, to the surprise of many, entered a new period of increased stability:

Tbilisi believes Russia will be mired in Ukraine for years, if not decades. Amid this significant distraction, Russia’s power has diminished in the South Caucasus, giving other actors—chiefly Turkey and Iran—greater space for maneuver. The invasion of Ukraine has ended the post-Soviet era and ushered in the effective end of exclusive Russian dominance in the South Caucasus.

This means more room for bolder foreign policy moves from Georgia to exploit Russian weakness. The expectation is that Moscow could push Abkhazia and South Ossetia—which it currently props up—to make some conciliatory gestures toward Tbilisi that would create a semblance of potential conflict resolution. Those could include closer economic ties between the two territories and the rest of Georgia, and even some minor political contacts with Tbilisi. Another move could be to facilitate free movement among the local population and reduce the number of kidnappings of Georgian nationals by Russian-Ossetian forces.

As a result of the Azerbaijani attack on the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh on September 19 and the forced exodus that followed it, this region will soon be empty of Armenians—for the first time in more than two millennia:

Five days before the Azerbaijani attack on the enclave a representative of the US government said that the USA would not tolerate the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh. Now it has happened and Washington seems to tolerate it, if the lack of sanctions on Azerbaijan are any indication.

There is reason to remain concerned about Azerbaijan’s plans. After the suppression of the Karabakh Armenians, the president of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, reiterated what he has said before: that he sees what he calls “Western Armenia” as historical Azerbaijani territory that Azerbaijan therefore has the right to reclaim. By this he means Armenia. In these plans, he has the full backing of Turkey. The first target will be the southern part of Armenia, the province of Syunik, which Azerbaijan calls Zangezur.

Resolute action from the West is needed to ensure that the aggressive Azeri regime does not, in its current victory rush, embark on new military adventures.

In taking Karabakh, Azerbaijan’s president avenged his father. Aliyev’s actions have loosened Russia’s decades-long grip on the strategically important South Caucasus region which is crisscrossed with oil and gas pipelines, lies between the Black and Caspian seas, and borders Iran, Turkey and Russia.

Tbilisi accuses Ukrainian official of plot to overthrow Georgian government:

Tbilisi has accused a senior Ukrainian official of trying to topple the Georgian government, amid a time of fraught relations between Kyiv and the Caucasian country. Georgia’s State Security Service claimed Georgi Lortkipanidze, the deputy head of Ukrainian military intelligence, was “plotting” to “violently overthrow” those in power this winter. Lortkipanidze is a former member of a strongly pro-Western Georgian government.

… Under the increasingly pro-Russian Georgian Dream party, Tbilisi has allegedly helped the Kremlin, even though a majority of Georgians support Ukraine. This is at least the seventh time since Georgian Dream came to power in 2012 that officials have claimed a coup was looming. Several opposition figures suggested the statement was an attempt to distract from a scandal surrounding the sanctioning of a former chief prosecutor by the US for his alleged connections to Russia.

Tbilisi court convicts protester “for holding blank sheet of paper.” Some have likened the police’s actions to Russia’s crackdown on protesters, where in recent years, Russian police have arrested several people for holding up blank sheets of paper during protests.

If you’re looking for a clear exposition of the causes and timeline of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, this New Yorker article is excellent.

A thirty-five-year war reignited last week. Hundreds of people died. Tens of thousands may have been displaced. The world, focussed on the United Nations General Assembly and the war in Ukraine, barely noticed.1 …

The Nagorno-Karabakh independence project has ended. But, Grigoryan told me, the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict is not over. “Azerbaijan has the military capability to take over southern Armenia, possibly on the pretext of needing a corridor to Nakhchivan.” Russia may have an interest in maintaining a military presence in the region, and further conflict could serve as the pretext. For now, the Russian media machine is working to destabilize the political situation in Armenia. Russia’s chief propagandists, at least two of whom happen to be ethnic Armenians, have blamed the defeat in Nagorno-Karabakh on Pashinyan. They have unleashed diatribes against him, employing obscene language. Under a special legal arrangement between the two countries, Russian television is widely broadcast in Armenia. “I have understood that Armenia should not insert itself in the games big countries play,” Martirosyan, the publisher, said. “Because the big ones will have a spat and kill a small country. Or at least hurt it very badly.”

Repression regains a foothold at the Writer’s House in Tbilisi. A political appointee has taken over as head of this cultural centre, the gem of Georgian literary society:

After first embarking on a series of mass firings across museums, the film institute and cultural archives, Tsulukiani then set about appointing prosecutors, lawyers and, in one case, the former head of a penal rehabilitation centre as the new directors of national cultural institutions. “Loyalty and total agreement” is how one former museum director described the characteristics of those who were allowed to remain in office. Autocrats fear the arts precisely because they can’t control the response and, as under most authoritarian-lite governments, Georgia’s cultural world has been a reliable canary for the oxygen left in the country’s democracy.

Armenia: Cast adrift in a tough neighborhood. While the Caucasus nation might want to reduce its reliance on Russia for a more reliable ally, Western nations have offered moral support but little else:

On the day Azerbaijan’s military sliced through the defenses of an ethnic Armenian redoubt last week, American soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division had just finished a training mission in nearby Armenia, a longtime ally of Russia that has been trying to reduce its near-total dependence on Moscow for its security. The Americans unfurled a banner made up of the flags of the United States and Armenia, posed for photographs—and then left the country.

What the Dissolution of Nagorno-Karabakh Means for the South Caucasus:

The Azerbaijani military has been surprisingly restrained as refugees stream down the Lachin Corridor. It looks like Baku wants to avoid being accused of ethnic cleansing, so it avoids subjecting departees to interrogations or serious checks. Just a few weeks ago, it would have been impossible to imagine such a hands-off approach: in its ten-month blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan arrested a sixty-eight-year old man accused of crimes during the First Karabakh War who was attempting to travel to Armenia for medical treatment.

Even so, Azerbaijan has detained a couple of men attempting to flee Nagorno-Karabakh, including former Armenian field commander and local politician Vitaly Balasanyan and Russian-Armenian billionaire Ruben Vardanyan, a former state minister of Nagorno-Karabakh who called on Karabakh Armenians to fight to the last bullet. These detentions hint at Azerbaijan’s unofficial rule: only Nagorno-Karabakh’s political elite need fear prosecution.

… However painful, Armenia’s defeat in Nagorno-Karabakh has not prompted it to drop out of discussions about a broader peace treaty with Baku. On the contrary, this process has been given fresh impetus. … The text of a peace agreement was more or less ready even before Azerbaijan’s recent capture of Nagorno-Karabakh. If Baku feels the process is dragging on unnecessarily, it could raise the stakes by not only demanding a land corridor through Armenia to the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, an Azerbaijani exclave bordering Turkey, but by laying claim to internationally recognized Armenian territory. Aliyev hinted at the latter in a recent meeting with Turkish President Recep Erdoğan, when he mused about Armenia’s post-Soviet borders in a similar way to which Russian President Vladimir Putin speaks about Ukraine.

As soon as Armenia and Azerbaijan sign a peace agreement, Turkey is likely to open its border with Armenia (which has been closed since 1993). Once this happens, economic factors will begin to come into play. Considering Erdoğan’s talent for manipulating his partners, an open border could be a powerful tool of influence for Ankara.

Meanwhile …

No, of course German soldiers weren’t found killed in a Leopard tank in Ukraine. (How is it that people still can’t recognize obvious Russian disinformation campaigns like these?)

Kyiv’s counter-offensive is “gaining ground,” says Stoltenberg.

Russia said that it plans to raise defense spending by almost 70 percent next year, funneling massive resources into its Ukraine offensive to fight what it calls a “hybrid war” unleashed by the West. (I remember what happened last time they tried to outspend us.)

At least 59 people killed in twin attacks on mosques in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan provinces in Pakistan:

No group has claimed responsibility for the Balochistan bombing, which comes amid a surge in the number of attacks claimed by militant groups in the west of the country before national elections scheduled for January next year. The Pakistani Taliban, an umbrella group of various hardline Sunni Islamist groups, denied it had carried out the attack. Islamic State has claimed previous deadly attacks in Balochistan and elsewhere. At least one expert suggested the coincidence of the two attacks could suggest that two different branches of the Islamic State in Pakistan could have coordinated the blasts.

I think the world noticed. New Yorkers, I’d gather, largely did not. But I’m not sure that New Yorkers constitute “the world.”

Yeah, “the world barely noticed” doesn’t really line up well with the headlines in many outlets for days on end.

Melik Kaylan: "As this column has often argued, the Central Asian C5 republics are gradually democratizing, expanding economically and bonding together very intentionally to avoid new kinds of dependence on nearby hegemons."

Or, https://www.bbc.com/news/explainers-59894266 (Jan 2022)- "Security forces in the Central Asian country of Kazakhstan say they have killed rioters while trying to restore order... Meanwhile, troops from neighbouring countries, including Russia, have been sent to help "stabilise" the situation. "