In closeup, say through the eyes of an infantryman on the firing line, battle is a study in chaos. To his battalion commander, striving to form a picture of the whole from the reports flowing into his tactical operations center, battle is like a puzzle with several missing pieces. Farther back, at higher headquarters and on up to the political leadership, the clarity supposed to come with distance is an illusion. Often the symbols and arrows on a situation map conceal as much, perhaps more, than they reveal.

To make sense of it all, a commander or observer needs intelligence, imagination, and a sense of context. The study of military history provides that context: Always, there are historical precedents or contrasts that help to dissipate the fog of war. If, for example, one compares the Battle of Waterloo (1815) to the opening round of the Great War (August 1914), a great deal that at first glance seems puzzling in the latter case becomes clear.

The Russo-Ukrainian War is of a size and character making it necessary to go back as far as the Second World War for a precedent and for me, one comes readily to mind: the Battle of Normandy in the summer of 1944.

The situation on the main front of the present war may briefly be summarized as follows. The Ukrainian Army is attacking with the immediate objective of achieving an operational breakthrough, i.e. an advance deep enough to undermine some sector of the Russian line. The Russians, of course, seek to prevent that from happening. To that end, they’ve covered much of their front with a network of field fortifications, obstacles, and minefields. Additionally, their destruction of the Kakhovka Dam in June caused major flooding on the southern sector of the front, depriving the Ukrainians of perhaps their most promising axis of attack.

The Ukrainian command appears to have decided against concentrating their mobile forces for a major attack on a single axis. Instead, Ukrainian forces are making limited advances in various areas, and this appears to have disrupted the Russian Army’s operational reserves, fixing them in place along the front. If, therefore, the Ukrainians succeed in scoring a breakthrough in one sector, the Russians will have no uncommitted reserve forces to parry the thrust.

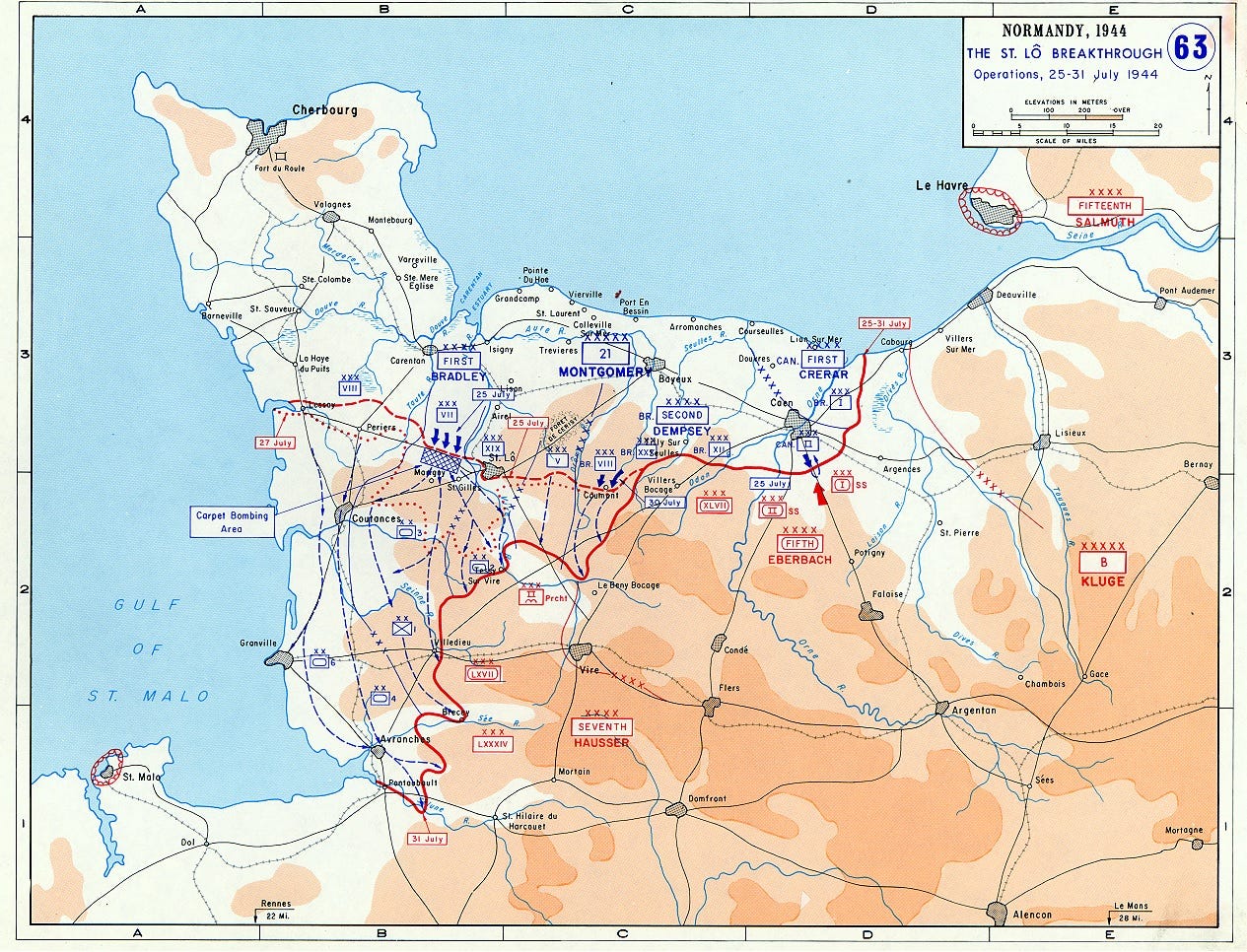

This situation bears a striking resemblance to that faced by the German and Allied armies in Normandy after the consolidation of the latter’s bridgehead. D-Day was 6 June 1944, and by early July that bridgehead extended from the vicinity of Caen in the east to the Atlantic Ocean south of the Cotentin Peninsula. From that point forward, the Allied objective was to break out of the bridgehead. The German objective was to prevent a breakout or, more realistically, to delay it as long as possible.

The OVERLORD plan had called for the early capture of the city of Caen and the high ground beyond the city, this to ensure that the British Second Army’s sector of the bridgehead was sufficiently deep to accommodate follow-on forces in preparation for a breakout. The Germans for their part realized that an Allied breakout in the Caen sector would open the way to Paris and trigger the collapse of their whole line. So they fought hard to prevent that: On D-Day and for weeks afterwards the defenders managed to repel every British attempt to take the city. Even when Caen itself was finally captured, the Germans still clung to the high ground beyond.

The Allied commander in Normandy was General Bernard Law Montgomery, the primary author of OVERLORD, and the failure to take Caen compelled him to modify his plans. The British would continue to act offensively on the Allied left flank, threatening a breakout and attracting German reserves to that sector—this to facilitate a breakout by US First Army on the opposite flank. The American attack, codenamed COBRA, would go south, then east, unhinging the German left flank and, if all went well, encircling and destroying the German defenders of Normandy, Seventh Army (facing the Americans) and Fifth Panzer Army (facing the British). There was one problem, however: the bocage.

The terrain on the American sector of the Normandy front was mixed woodland and pasture, with fields and serpentine country lanes bounded by low ridges and banks crowned by tall thick hedgerows, severely limiting fields of observation and fire. The fields were dotted with farm buildings stoutly constructed of stone. This, the bocage country, was ideal ground for the defensive employment of machine guns, mortars and infantry antitank weapons. The Germans with their customary efficiency soon established on this ground a defense in depth that repeatedly frustrated American attempts to penetrate it.

The one weakness of the German position was the lack of an operational reserve. It might be difficult to overcome the bocage defenses, but if the Americans did achieve a breakthrough, the Germans had no forces available restore the front. The panzer divisions that might have served to do so were in the Caen sector, fixed in place by persistent, though none too successful, British attacks.

Throughout July, the apparent lack of progress in Normandy brought much criticism down on Montgomery’s head. His insistence that everything was going according to plan merely exasperated the Americans, who saw clearly that Montgomery’s original scheme of operations had failed. Winston Churchill, who had never been enamored of Montgomery, was equally irritated. He let it be known that if General Eisenhower, the Allied supreme commander, wished to sack any British general the Prime Minister would not object. Monty was clearly meant.

Behind those scenes of discontent and acrimony, however, the military situation was developing as Montgomery intended. The threat in the Caen sector compelled the Germans to commit most of their panzer divisions there, while German strength against the Americans gradually dwindled away. Allied air superiority—approaching air supremacy—was most effective in isolating the battlefield by interdicting the movement of German reinforcements and supplies. Thus when COBRA was launched on 25 July, the Americans soon scored a deep breakthrough, leading to the collapse of the German line. Though the planned encirclement of the defending forces did not come off, the German Army in northern France was shattered. The retreat of its remnants only came to a halt on the western border of the Reich.

The similarities between Normandy 1944 and Ukraine 2023 are obvious enough. It remains to point out the differences. The most important one is that unlike the Allies, the Ukrainians do not enjoy air superiority. This limits their ability to provide their ground forces with close air support or to isolate the battlefield, though long-range rocket artillery and missiles make up some of the difference. Added to this is the fact that the Ukrainians, unlike the Allies, do not enjoy overall numerical superiority. For that reason, their operations must be so conducted as to minimize casualties. Nor is it likely that a breakthrough on one sector of the front would undermine the entire Russian line. On the other hand, the Russian Army in Ukraine is considerably less skilled and determined than the German Army in Normandy, rendering it more likely that a modest Ukrainian breakthrough could have major consequences.

In its latest assessment (August 24) the Institute for the Study of War (ISW) notes that the Ukrainians are “further widening their breach of Russian defensive lines” in the western Zaporizhia Oblast area. On a ten-kilometer front, Ukrainian forces have overrun the first line of Russian field fortifications and captured most of the village of Robotyne. Sometimes in a battle, things happen gradually, then all at once. Since the Russians have no uncommitted operational reserve, they can only reinforce the western Zaporizhia sector by taking forces from other areas. The ISW reports that lateral redeployments of Russian forces from Kherson Oblast to the Zaporizhia Oblast are underway, further evidence that the Russian command is concerned about the situation in the latter sector. But as the Germans found in Normandy, robbing Peter to pay Paul culminates in operational bankruptcy.