You Asked. I Answer.

Part V: Can the UK be saved? Why are the French suburbs so ugly? What do the Thai think of their neighbors? Plus: Why we have a culture war. Also: Notes on the News.

I’m interested in your perspective on the UK, the direction UK society has taken since Brexit, whether the Tory party is ripe for replacement by something new or whether it can be revived, and the likely direction the next government will take. Are the Brits more or less polarized and cranky than we in the US are? Was Brexit always doomed to massive failure, or has the follow-up been horribly mismanaged, or am I missing something? Is the party of Margaret Thatcher in terminal decline, or are there new and dynamic leaders emerging anywhere? Has the Labour party become more or less sane and pragmatic? What will it take to return growth and prosperity, and is it likely that any majority or coalition can be formed to do those things?

I can’t possibly confine myself to a short reply with a question like this, so I’m going to put this on the list of questions to answer later, at length. But here’s some reading I recommend.

First, Cosmopolitan Globalist favorite John Oxley has struck out on his own at Joxley Writes. He’s an excellent observer of the Tories, in particular, and he treats many of the topics you mention. I recommend this entry: Britain’s Martin Lewis Problem—Martin Lewis is an expert on saving money—in which he argues that both parties have become “trapped in the mindset of saving and re-apportioning, rather than increasing our national wealth.”

… Britain now seems all too comfortable with cutting its coat according to its cloth. The spirit of the Money Saving Expert is endemic. Both the country and its households are stuck in a scarcity mindset, focused on coping and managing, rather than leveraging the biggest changes. The country needs to allow itself to become richer. This is, in part, an elite problem—but our politicians largely respond to electoral incentives, rather than leading them.

He links to a post by Sam Bowman, who’s also on Substack and also worth reading, although he writes very infrequently. I presume from your question that you’re well aware how disastrously the UK is performing, economically. John and Sam both argue that its policymakers—of all parties—are barking up the wrong tree. Britain’s economy, Bowman argues, is now akin to that of a developing country, “more like Poland than it is like the United States in terms of the kinds of growth it needs to do.” But British elites don’t seem to realize this:

There is virtually no recognition of how bad things are among British elites. Stefan Dercon, author of Gambling on Development, has a theory about what allows developing countries to experience sustained economic growth: they need their elites to come to an agreement to pursue it. The reforms needed to grow are painful and unpopular in the short-run. Regimes that do them without an “elite bargain” behind them are opening themselves up to being removed. Similarly, when one party in the UK proposes planning liberalization, almost inevitably the others swing heavily Nimbyish.

In the UK, the preoccupations of the “elite”—by which I mean the people, left and right, in politics, government and media whose views shape those of the country—are with things like Net Zero (above all), inequality, obesity, delivering Brexit, regulating Big Tech, data ethics and privacy, cutting immigration, gender and racial pay gaps, and other priorities that are either unrelated to, or diametrically opposed to, making the country richer.

His essay on Boosters and Doomsters is also excellent.

I also recommend Giles Wilkes’s blog, Freethinking Economist. He has an excellent post here about what might be done to restore growth. The bright side of how badly the UK has fallen behind in productivity, he argues, is that growth “is less about performing achingly high-tech, best-in-class actions. You just need to catch up to what is possible elsewhere.” Read the whole thing.

Also good is this longer policy report by Tim Pitt, an Onward Policy Fellow, titled The Road to Credibility: Conservative Economic Principles for the Path Ahead. It’s a detailed answer to your question about what it would take to return to growth and prosperity, and a credible one, I think. He is not optimistic:

A significant part of the growth slowdown is the result of long-term structural forces, forces which will likely continue to weigh on growth in the coming decades. Against this backdrop, even a successful pro-growth agenda is unlikely to return trend growth to its pre-financial crisis levels.

Thus, he concludes, “even if we succeed at raising the UK’s growth rate (as we must), policymakers will need to focus more on economic inequality and fiscal discipline.”

On the former, the Conservatives must decide whether to acknowledge that existing high levels of economic inequality are a problem, and come up with a plan to address them; or convince the electorate that inequality does not matter. On the latter, lower growth combined with demographic and other long-term pressures will mean a formidably challenging fiscal position. And though it will be an uncomfortable fact for many Conservatives, an aging population is likely to mean that the state will continue to grow, at least in some areas.

Grim stuff. On reading it, I’m struck anew by the way the United States keeps pulling off economic miracle after economic miracle. The UK can’t seem to do anything right, economically. The US can’t seem to do anything wrong.

Opportunity Lost, by the economist Ben Ramanauskas, is another newsletter about the questions that interest you. (Here, he makes the interesting point that just as only Nixon could go to China, only Labour can reform the NHS.)

I’ll come back to your question, especially the part about Brexit. (Short answer: It was always doomed.)

In Bangkok, did you get an idea of how the Thai viewed surrounding nations?

They viewed the Lao as backward country bumpkins. (Mind you, I was in Bangkok, where people have the typical big-city prejudices; they viewed people from rural parts of Thailand the same way.) And much as Americans tend to think Canadians are, basically, just Americans who adorably insist that they’re an independent country, Thais don’t really take it seriously when the Lao protest that they have their own country and culture.

They don’t see the Lao as ethnically different, as they do, say, the Vietnamese or the Cambodians. I believe the stereotype about the Vietnamese was that they were tough, serious, clever, and rather intimidating. I can’t recall having many conversations with Thais about other neighboring countries. (Thais were proud that unlike some people they could mention they had never been colonized.)

There’s a very large and typically successful overseas Chinese population in Thailand, but they’re completely assimilated. I may have missed some of the subtleties in the relationship, but I don’t think this shaped their views of mainland China. The Thai saw themselves (rightly) as having better manners than mainland Chinese. But they understood Chinese culture well—I think quite a few studied Chinese classics in school—and seemed to like them well enough.

They saw Singapore as no fun at all. Singapore, emphatically, was not sabai sabai. But here I may be confusing the views of the kind of Thais I’d talk to about this with those of the wider public. The people with whom I’d have had a conversation about the relative sabai-ness of Singapore would have been journalist, and foreign journalists certainly viewed Singapore as the last place you’d want to go on your three-day weekend. Thais from other walks of life may have admired Singapore’s economic development.

I think they saw Burma as a tragedy. An unfortunate place. And they saw the Burmese as poor people for whom they should have pity, though nationalists remained aggravated by the memory of Ayutthaya. (Ayutthaya was the Thai capital; the Burmese sacked it in the late 1700s.) I think the Burmese also had a reputation for being prone to smuggling drugs or in some way being criminal? There was a sense of the borderlands being dangerous. Probably they felt the same kind of pity for Cambodians, too. And the nationalists probably felt the same kind of instinctive hostility—the thought of the place raised their hackles. But I can’t say I remember having a single conversation about Cambodia with a Thai. With other Westerners, yes. But I don’t remember it coming up with Thais.

I don’t think Thais thought about Malaysia much at all, apart from feeling that the border area is a bad place that isn’t safe. (People in Bangkok thought that, anyway.)

Were you ever at the UW French conversation table downstairs in the HUB in the 80s, or early 90s? Do you remember any of the French TAs who ran that table?

I was in the HUB all the time in the early 80s. My friends and I hung out for hours at a particular table in the cafeteria, and I remember it so well. I get terribly nostalgic thinking about it. (Hi Shahin!) It’s possible I joined the French conversation table. I was taking French classes, after all, so I must have known about it. But for the life of me I don’t remember it. I certainly don’t remember any TAs. Did I even have French TAs? I recall the classes were small-ish.

I still have the textbook I used in my attic: Découverte et création: Les bases du français moderne. (It’s an excellent textbook.)

In re. the cités in France’s major cities: When discussing the causes for the riots, no mention was made of density in these buildings. High density living quarters plus summer can be a catalyst. I don’t know the history of these buildings. Were they built after World War II to house European migrants from within Europe at the time? Were they unconsciously made to keep the un-French out of the center cities?

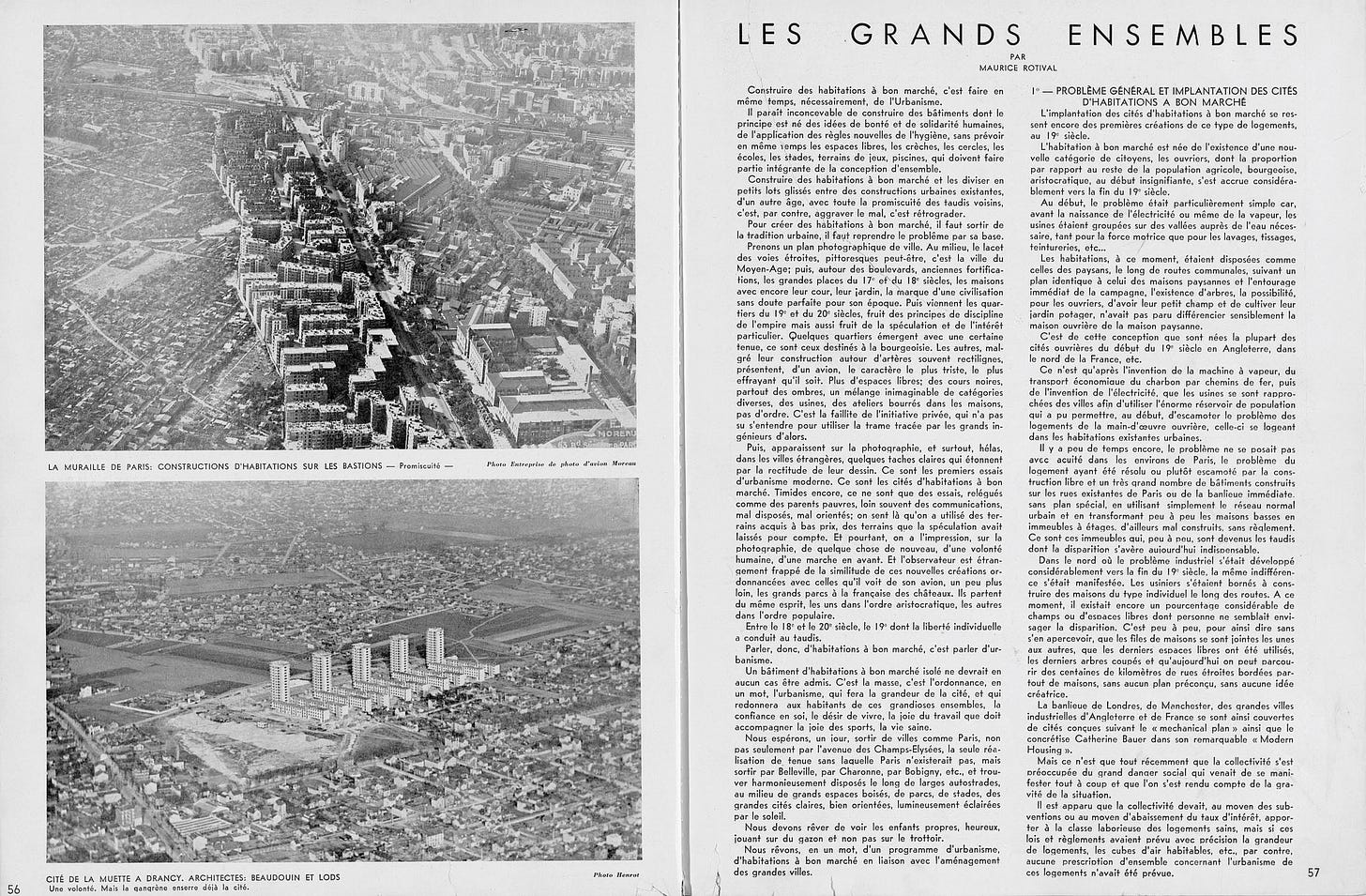

They were mostly built in the 1950s and 60s in response to a severe postwar housing shortage. The wave of construction was part of the so-called Trente Glorieuses, the thirty years from 1945 to 1975 marked by reconstruction and rapid economic growth. Immediately after the Second World War, the priority was reconstruction, not housing. The first of Jean Monnet’s five-year plans focused on rebuilding transport infrastructure and the means of production, and at the time, the construction sector in France wasn’t able to build mass housing: Construction firms were mostly small businesses that used traditional methods.

But the crisis was severe, intensified by the war’s devastation, urban overcrowding, and the French baby boom. Out of 14.5 million homes in France, four in ten didn’t have running water. Only a quarter had an indoor toilet. There were, the government assessed, three million overcrowded dwellings and a deficit of three million homes, with 8.5 million citizens inadequately housed. And a rent freeze—in place since 1914, and only partly mitigated by a 1948 law—didn’t favor private investment.

The idea of building large complexes on the outskirts of the city gained support because of the widespread sense that urban life was dangerous and unhealthy, and new buildings, outside of the city, would somehow be more sanitary. The winter of 1954 was especially harsh, causing the government to build temporary emergency housing estates. Within a year, they collapsed into unsanitary hovels. That was why they decided to prioritize building massive collective housing blocs made of prefabricated concrete. The sole objective was to build a lot of housing, quickly. And this they did. In 1946, there were fewer than 500,000 low-income housing units in France; thirty years later, there were nearly three million. A third of them were massive concrete towers or bars. More than 40 percent were built on the outskirts of Paris.

Another reason for building this way was the power of reinforced concrete companies, who had grown fat during the Second World War by collaborating with the Nazis in building the Atlantic Wall. What’s more, road and bridge engineers—who naturally loved reinforced concrete—were overrepresented in France’s postwar administrative and technical cadres. So when they considered the problem of mass housing, they decided reinforced concrete was the ticket.

The state encouraged the use of industrial production methods. They wanted to build as simply as possible, to save time. Prefabrication allowed them to build with unskilled labor instead of the highly trained craftsmen who built the Paris everyone loves. Aspects of this way of building, from the industrialization and mechanization to the organization of the construction site and concrete prefabrication, were fetishized as new architectural principles: The government's approach was greatly influenced by the architectural and urban planning concepts of modernism, which prioritized functionality and efficiency. Le Corbusier, of course, was the key figure. The people who built these horrors really seemed to believe they were all sensational and very modern and futuristic and people would just love living in their concrete boxes. (Le Corbusier called them “living machines.”) From the start, the press railed against these towers, correctly intuiting that they were not just an aesthetic but a moral disaster.

France wasn’t the only country with a housing crisis, but it was the only Western capitalist country to build massive, soulless, alienating housing bars and towers—a complete breach of the existing urban fabric—in response. You otherwise only saw these in the socialist bloc, as for example in the 1955 Khrushchev habitat.

The buildings are unspeakably ugly and alienating. Erecting them was a criminal mistake. Since no other Western country found it necessary to build this kind of thing, I simply don’t buy the argument that it was economically necessary. I believe deeply that the demoralizing effect of this architecture—demoralizing the strictest sense, because the overpowering ugliness appears to erode the moral sensibilities of those entrapped in them—is greatly to blame for the criminality of the French suburbs.

They weren’t build for migrants, no, but for the French working class, although the housing crisis was as acute as it was because hundreds of thousands of Spaniards, Italians, Poles, Portuguese, and North Africans were migrating to France. But the idea was for these to be dwellings for factory workers. They were built near factories. (The aesthetic was even meant to evoke a factory.) They were built on the outskirts of cities because land was cheaper and more plentiful there; there was no conscious plan—no plan at all—to keep immigrants out of cities.

For many, moving into one of these large complexes was a step up in creature comforts—the buildings had hot and cold running water, central heating, indoor toilets, elevators. Initially, the residents were industrial workers, families that had previously been living in unsanitary conditions, repatriates from Algeria.

But from the beginning, people hated these places. They hated the lack of shops, the lack of transport, the lack of neighborhood life, the noise. So the first thing residents wanted to do, as soon as they had the money to do it, was move out. This meant that only people at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder wound up living there, and increasingly, over time, the bottom rung was occupied by migrants imported from former French colonies to fill postwar labor shortages.

I’ve written about other aspects of this story here.

Here’s a collection of photos by Laurent Kronental.

Why we have a culture war

For the past few years, the Cosmopolitan Globalist has oh-so-gradually grown. Every year, we have more readers and subscribers than the year before, which is the main thing. But it can’t be said that our growth has been explosive. We fight like the dickens for every new subscriber—I dance, I sing, I caper! I wheedle!—and every single new subscriber is cause for major celebration.

The past few weeks have been demoralizing: Subscriptions have been flat and even (to my horror) went down one day, despite my entreaties. This happens from time to time. People subscribe on an impulse and discover it’s not their thing; their subscription runs out and they don’t renew. It’s not necessarily personal. Some people are just stupid and evil, right? I tell myself to focus on the long-term trend. In the short term, the numbers go up and down, but over the long term, the trend is positive.

Still, it’s easy to get discouraged during the times when the numbers are flat, especially when you work alone, even more so if you’ve married your self-esteem to your subscription numbers. (Don’t tell me I shouldn’t do that, because that’s what’s wrong with kids today. Self-esteem is earned. People who contribute nothing of value to society should not esteem themselves highly. Price signals are the way we communicate the value of goods and services. If no one is willing to pay for CG, it signifies that it literally has no value, and someone who spends all day, every day, contributing nothing of value to society should not esteem herself.) So when I’ve been working hard for days but the counter doesn’t budge—or worse, goes down—I get worried.

But in the past few days, I’ve had a sudden surge of new readers and subscriptions. And we know why, don’t we? Because the name “Donald Trump” was in the headline—twice in a row.

(Welcome, new readers! Thank you, new subscribers!)

Do you realize how tempted I am to keep writing about Donald Trump? I could write about him every day! There’s no limit to my loathing of the man, and you keep baiting me in the comments.

“But I love it when you write about Donald Trump,” my brother said to me when I explained this dilemma to him. “Why don’t you just go full culture war and write about the stuff that makes money? Transgender athletes on Monday, Hunter Biden on Tuesday, Bud Light on Wednesday—”

“But I’d be a sellout, Mischa.”

“Yeah!”

I thought about it. It’s a puzzler, isn’t it? What do you think: If I wrote about Donald Trump, Hunter Biden, the Deep State, Tavistock, MAGA, Black Lives Matter, JK Rawling, Dr. Fauci, Drag Queen Story Hour, Jordan Peterson, and critical race theory whenever my bank balance gets low, would I be a selling my soul? Or would I be a more productive member of society?

I’m still thinking it over. It does seem wrong that Bari Weiss makes more money than I do.

Notes on the News

‘Dai,’ enough, stop it, let it go. The Israeli government must give up on any further judicial reforms.

Benjamin Netanyahu’s day of infamy. On Monday, Netanyahu earned his place in history as the man who tore Israeli society and led it to civil war:

On Monday, Israel’s longest-serving prime minister secured his place in history as an enemy of the Jewish state, and an antichrist of the Zionist idea.

Netanyahu’s damage to what has been built here over nearly 150 years is about what he did, why he did what he did, how he did it, who he did it with, and who he did it without.

What he did was to undermine the justice system that has been our pride and other people’s envy. Worse, he did this while inventing conspiratorial charges, like Joe McCarthy, Joseph Stalin, and Queen Jezebel. Worst of all, he incited us Zionists to fight each other: knowingly, repeatedly, loudly, and as a strategic aim.

These alone are crimes against the Zionist ideal that was, and remains, not only to gather the Jews in their ancestral land but to reprogram them, to unite them, to create New Jews – hardworking idealists who would collectively make Zion a place “filled with justice, where righteousness dwelt” (Isaiah 1:21).

(This was published in the Jerusalem Post. The author is its former executive editor. This is not, in other words, some petulant leftist. Far from it. The fury in Israel is incandescent. I have never heard Israelis sound this way before. It is completely unprecedented.)

A staggering number of Israelis are seriously considering emigration. “What this government is doing—and as I see it, this is the first anti-Zionist government in Israeli history—could have a devastating effect on employment, and that could drive many Israelis out.”

★ Micah Goodman: An incipient internal intifada:

We’ve seen strikes in Israel. Teachers strike, unions strike, civilian pilots strike. But the military never went on strike. That never happened. This is unprecedented, and it’s very obvious why it never happened. I mean, look around. Look at Hezbollah. Look at Hamas. Look at Iran. This is not something that Israelis do.

But once it’s done, there is a precedent. It will be very attractive to replicate this precedent in the future because this action, this very extreme action, is being normalized in Israel. The mainstream media is sympathizing with this step. Three former chiefs of staff are embracing this step. So this very extreme step is experienced as something very not extreme, very normal and legitimized, and it’s also very effective. And that combination, Amanda, of a step that’s experienced as legitimate and effective, I think will change Israel for years to come.

… By the way, something very interesting. You know how the metaphors “on right and left” were created in the French Revolution and the National Assembly? People that sat to the right were for status quo and against change. People that sat to the left were for change. What is radical? Radical, radix in Latin is a “root.” So radical change is to change something from its root. So it’s very interesting that in Israel, the left is for the status quo and the right is for radical change.

So you ask yourself what happens when right-wingers start to think like left-wingers and left-wingers think like right-wingers? What happens? Well, what happens, is that’s Israel today, welcome to Israel.

★ Yossi Klein Halevi: The wounded Jewish psyche and the divided Israeli soul. Understanding Israel’s moment of truth—from the war on Start-up Nation, to the moral crisis in Orthodox Jewry, to the author’s personal failure of empathy for political opponents:

The greatest danger to the Start-up Nation is an emigration of despair. In fact, that exit has quietly begun. And if the government continues to fundamentally transform Israel in its image—an alliance of ultra-nationalists, religious fundamentalists and the merely corrupt—we will experience our first ideologically motivated mass flight, among those who connect this country to the global economy and the democratic world.

In one sense, what is happening to Israel is hardly unusual. Populist wars against elites are being waged all over the world. And yet Israel is unique: While other societies can endure a populist wave of resentment and even violent hatred, Israel’s long-term survival in the Middle East depends on maintaining its modernist elite (while expanding the entry points into the elite to ensure greater diversity). The alternative is gradual—or perhaps rapid— descent into a dysfunctional society led by corrupt counter-elites, precisely the scenario modeled by this government. …

The far-right zealots are in charge of ensuring that Israel becomes an outcast among democratic nations. The ultra-Orthodox state-within-a-state is laying the ground for the eventual ruin of the Israeli economy, forced to maintain an ever-expanding, chronically under-productive population. And a thoroughly corrupted Likud is in charge of dismantling the independent judiciary, the last line of defense for Israeli democracy. This government, which promotes itself as the guarantor of Israeli security, is the greatest internal threat to our security in the nation’s history.

Over and over, protesters tell interviewers variations of the same story: I’m doing this for my father who was wounded in the Yom Kippur War, for my son who was killed in Lebanon, for my grandparents who were uprooted from Iraq or who survived the Holocaust, for my great-grandparents who helped build the state. Now, they say, it’s my turn to defend the country.

From Bret Stephens: Israel’s self-inflicted wound:

The crisis in Israel is sometimes described as a battle of left against right, secular against religious, Ashkenazi against Mizrahi Jews. This is a vast overgeneralization: Netanyahu is a scion of the secular Ashkenazi elites, while many in the opposition, like former Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, are religiously observant and right-wing.

What is true is that the new dividing line in Israel, as in so many other democracies, is no longer between liberals and conservatives. It’s between liberals and illiberals. It’s between those who believe that democracy encompasses a set of norms, values and habits that respect and enforce sharp limits on power and those who will use their majorities to do whatever they please in matters of politics so that they may eventually do whatever they please in matters of law.

Believe it or not, this is an important article by Tom Friedman. The Biden Administration has been using him as a conduit for their policy ideas recently: Biden is weighing a big Middle East deal.

After discussions in the past few days among Biden; his national security adviser, Jake Sullivan; Secretary of State Antony Blinken; and Brett McGurk, the top White House official handling Middle East policy, Biden has dispatched Sullivan and McGurk to Saudi Arabia, where they arrived Thursday morning, to explore the possibility of some kind of US-Saudi-Israeli-Palestinian understanding. …

[A] US-Saudi security pact that produces normalization of relations between Saudi Arabia and the Jewish state—while curtailing Saudi-China relations—would be a game changer for the Middle East, bigger than the Camp David peace treaty between Egypt and Israel. Because peace between Israel and Saudi Arabia, the custodian of Islam’s two holiest cities, Mecca and Medina, would open the way for peace between Israel and the whole Muslim world, including giant countries like Indonesia and maybe even Pakistan. It would be a significant Biden foreign policy legacy.

Second, if the United States forges a security alliance with Saudi Arabia—on the conditions that it normalize relations with Israel and that Israel make meaningful concessions to the Palestinian—Netanyahu’s ruling coalition of Jewish supremacists and religious extremists would have to answer this question: You can annex the West Bank, or you can have peace with Saudi Arabia and the whole Muslim world, but you can’t have both, so which will it be?

The Saudis seem to want three things: A US-Saudi defense treaty that commits the US to its defense in the event it’s attacked by Iran, a pledge from Israel not to annex the West Bank along with other (not yet specified) concessions to the Palestinians, and Washington’s help in building a civilian nuclear program, which presumably would become a nuclear weapons program the minute Iran conducts its first test.

I see a lot of ways that an explicit commitment to the Saudis could go wrong. For one thing, I doubt we could persuade Americans to go to war for the Saudis. Given this—and given everyone knows how little Americans would be inclined to do that—would such a promise be credible? What would the commitment involve? The details would matter. There’s a lot of room between “something like the Budapest Memorandum” and “something like NATO.”

But if a deal is really on offer, it could be worth considering. What do you think? There’s certainly a lot of haggling going on:

Top Israeli official says country won’t block Saudi civil nuclear program:

… Hanegbi addressed reports that Saudi Arabia is conditioning normalization with Israel on the United States helping it create a civil nuclear program, saying that Israel’s consent was not needed. “Dozens of countries operate projects with civilian nuclear cores and with nuclear endeavors for energy. This is not something that endangers them nor their neighbors.”

Mossad chief secretly visited DC to discuss Saudi deal.

Abraham Accords under strain. Here’s a more pessimistic view from the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington:

[F]ollowing the rise of extremists to top positions in the Israeli government led by Netanyahu, and intensifying Israeli military raids in the West Bank, there has been speculation that Abu Dhabi and Manama could cut ties with Israel. The collapse of the Abraham Accords is unlikely but so too is the prospect of other Gulf Cooperation Council states joining the accords. The Israeli government has its hands full trying to maintain its newly forged official relationships, and Israel must keep the accords alive if it wants to keep the peace-for-peace paradigm alive. …

Given the unlikelihood of other GCC states entering the Abraham Accords anytime soon, Israel is attempting to bring other Muslim-majority states into the “circle of peace.” Eli Cohen, Israel’s foreign minister, is reportedly working to normalize relations with Mauritania, Somalia, Niger, and Indonesia. However, there have been few public signs of progress. …

… [One] Israeli strategy for keeping the Abraham Accords alive is inducing strategic speculation. Israeli officials (and others) do so by suggesting that more official cooperation or “breakthroughs” with Gulf states are on the horizon. In turn, such speculation can be politicized or even framed to inaccurately portray the Abraham Accords as vibrant and expanding. While business between the countries has continued, the Abraham Accords have become increasingly unpopular in the Gulf streets, and doubts over the merits of the Abraham Accords as a framework for regional peace have also increased. …

Future visits by US officials to the kingdom may [like Lindsey Graham’s] be framed as a push toward advancing the Abraham Accords. Such visits will likely be accompanied by a flurry of speculative reports regarding the expansion of the Abraham Accords, irrespective of the likelihood of Saudi Arabia actually joining the accords in the near future. For example, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan gave a speech May 4 at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy shortly before traveling to Saudi Arabia. Sullivan stated that “getting to full normalization” between Israel and Saudi Arabia “is a declared national security interest of the United States,” spurring a flurry of speculative headlines regarding Sullivan’s trip to the kingdom and US efforts to facilitate Israeli-Saudi normalization. But despite the media hype, the White House readout of Sullivan’s meeting in Saudi Arabia did not even mention Israel.

Sovereignty may be the price for normalization with Riyadh. Amid reports on Saudi demands that Israel make “significant concessions” to the Palestinians before official ties are announced, Israel is signaling that the formula that worked for the Abraham Accords could work now too.

… What Israel can offer Biden and Saudi Arabia is to continue putting off the sovereignty issue for four more years, until the end of 2028. This is not an empty promise, as there is a very real chance of Donald Trump returning to the White House (as well as of other Republican victories). Thus, such a pledge would mean that even if a hawkish Republican president takes office in Washington, the fully right-wing government in Israel will not seize the opportunity to extend the country’s sovereignty, which some call “annexation,” despite the push to do so by many in right-wing circles.

Internal US politics is very much part of this story. The conventional wisdom in Israel is that Biden will have to decide by December whether he is all-in on such a deal. After that, the presidential campaign will be in full swing. Moreover, a full-fledged treaty with Saudi Arabia will require two-thirds Senate approval. The administration is wary that the GOP is unlikely to be inclined to give Biden such a historic accomplishment.

Also noted

Here’s more about what Turkey got in exchange for relenting on Sweden’s admission to NATO: US, Russia mum as Turkey escalates attacks against Kurdish groups in Syria and Iraq. Both the White House and the State Department remain silent as Turkey’s military campaign against the PKK continues “full blast.”

Though the US Central Command condemned the attack, both the White House and the State Department remained silent. To be sure, Washington’s diplomatic engagement with the Autonomous Administration has declined since Russia’s occupation of Ukraine in February 2022. Senior Syrian Kurdish officials were told to put off a planned trip to Washington in February even after being issued visas for it … This was likely to head off potential Turkish fury ahead of a NATO summit that was held earlier this month in Vilnius and where it was hoped Ankara would approve Sweden’s formal admittance into the alliance.

… “Fear of antagonizing Turkey during the NATO accession process is not helping here. Maintaining the status quo while US adversaries are moving their strategies forward isn’t enough. Washington should consolidate a proactive, pro-peace position on Turkey, North and East Syria, and the Kurdish question before the next inevitable crisis occurs.”

The Ukraine war is about to get worse. Collapsed grain and gas deals spell disaster for Europe.

Ukraine’s counteroffensive lurches forward: Key moment looms as more forces committed.

What happened to Qin Gang? Qin Gang, China’s new foreign minister and something of a political star, disappeared from public view on June 25. On July 25, after denying there was anything unusual about this for a month, the National People’s Congress Standing Committee replaced him with Wang Yi, his predecessor. It’s all very mysterious and no one understands it.

Fog around Qin Gang’s exit signals the Party hasn’t yet decided his fate:

… Qin’s removal from his position as foreign minister was announced by the National People’s Congress Standing Committee, China’s top legislative body, as it met for a special session on Tuesday. It came after Qin had not appeared in public for a month but no reason was given for the decision—unspecified health issues was the only explanation offered for his absence.

Qin’s downfall would be an embarrassment for Xi Jinping if serious problems were found, Zhu said, as he was “widely believed to be a favorite and protégé” of the Chinese president. “So to maintain domestic stability and avoid tarnishing Xi’s image, the party is likely to aim for a soft landing for Qin and minimize the fallout of the case.”

Niger junta arrests senior politicians after coup, debt issue cancelled.

Robert Zubrin evaluates the scientific and historic accuracy of Oppenheimer.

This is the best summary you’ll read of the latest twists and turns in the Covid origins debate. I don’t agree with every point he makes. I think it’s plausible that the authors of Proximal Origins deceived themselves, rather than conspiring to deceive the world. But his is a perfectly plausible way to interpret the evidence. (Washburne has also written one of the most comprehensive cases in favor of the lab theory. Although it will take you a bit of time, it’s completely accessible to the lay reader: just read it patiently.)

Kevin Drum offers another way to interpret the same leaked Slack messages. What Drum can’t explain, though, is why the authors were willing to stake everything on such a weak scientific argument.

Write about the culture war only when it is relevant to your writing about events outside the USA.

The western press is saturated with culture war stuff. I pretty much only need to breath the air to be enveloped in it. I read CG for all the worldwide stuff the western press ignores because so much of their space is consumed with culture war/political/Trump/clickbait stuff.

On the subject of French suburbs I will note that other countries did build similar high rise tower blocks but just not as extensively as in France. Think the Grenfell Towers in London(that famously burnt down) or the infamous Cabrini Green housing projects of Chicago. It's just no one else went quite as overboard as France did. I also think the fact that Charles De Gaulle Airport is located where it is(and itself is a huge monument to the influence of the concrete industry) and the fact you have to go through certain communities(St Denis, Aubervilliers, etc) to get to and from the city center of Paris means foreign tourists get exposed to a part of France they otherwise would probably not otherwise(The same could be said of JFK Airport in NYC and large sections of Queens like Jamaica that the average non New York would not otherwise see).

Compare this to Heathrow Airport and the West End of London. If the entirety of your travels to the UK is just going back and forth between Heathrow and the West End all you are going to be seeing is a subset of the UK that is extremely and abnormally wealthy compared to rest of the UK even with the economic turmoil of Brexit. Even a more "working class" neighborhood of London like Chiswick along the M4 route to and from Heathrow is probably going to be noticed by passing tourists more than anything else for the multi-story Audi and Mercedes Benz dealerships right along the motorway