I spoke last night to the Afghan family many of you have been helping—the S. Family, I’ll call them, since it’s not safe to identify them yet. (If you're new to the Cosmopolitan Globalist and you don’t know this story, it’s here.) They’re still in Pakistan, waiting for the Canadian government to finish processing their asylum application.

These are the steps for processing a privately-sponsored application:

They’ve been through every step but the final decision. They’ve passed the eligibility and admission screening. They’ve provided their biometric data. But whatever happens now is taking forever, and they’ve been warned it might be much longer.

How much longer? No one can say. They fear Pakistan will deport them back to Afghanistan before the Canadian government issues their Notice of Approval. They’re not wrong to fear this.

I’ve discussed this with them at length. We’re stumped. We can’t figure out why it takes so long. What, exactly, does the Canadian government do during this period? They need no further information from them or from us. They know exactly who this family is. They know that the money our readers contributed to sponsor them is in a Canadian trust fund, waiting for their arrival. The Canadian government works with JIAS, our sponsorship agreement holders, all the time. They have a good relationship with them. They know JIAS wouldn’t even send them an application if the people involved didn’t have a complete dossier, with every i and t dotted or crossed just right. They’ve interviewed every member of the family. They have their biometric information. I assume Canada queries databases around the world, looking for signs that the members of this family aren’t who they claim to be. But how long could that take in the Information Age? Not more than 48 hours, right?

Everything about their application is in order—they’ve said so. So what, exactly, happens during this period? (If anyone here knows, or can think of someone who might know, I’d be so grateful to be in contact with you. Just understanding the process would diminish the anxiety.)

Pakistan has been accelerating its deportation of Afghan refugees. Canada knows this. They sent a letter to the family to show immigration officials in Pakistan if they’re picked up. It asks that they not be deported because they’re in the pipeline for asylum in Canada. I’m glad they did this, but we have no idea whether something like this makes any difference. Pakistan (like the US) isn’t interested in these niceties, it just wants the refugees gone. Many are being deported despite the credible risk that the Taliban will torture and kill them, which is a violation of the 1951 Refugee Convention, and other countries have lodged protests, but Pakistan has explicitly pointed to what the United States is doing and asked why they should be required to do more for Afghan refugees than we are.

No other country, as far as we’ve been able to figure out, will allow them simply to wait in safety—bothering no one, taking nothing away from any local—while the Canadian government finishes this mysterious process. An Afghan passport is useless the world around. So they wait.

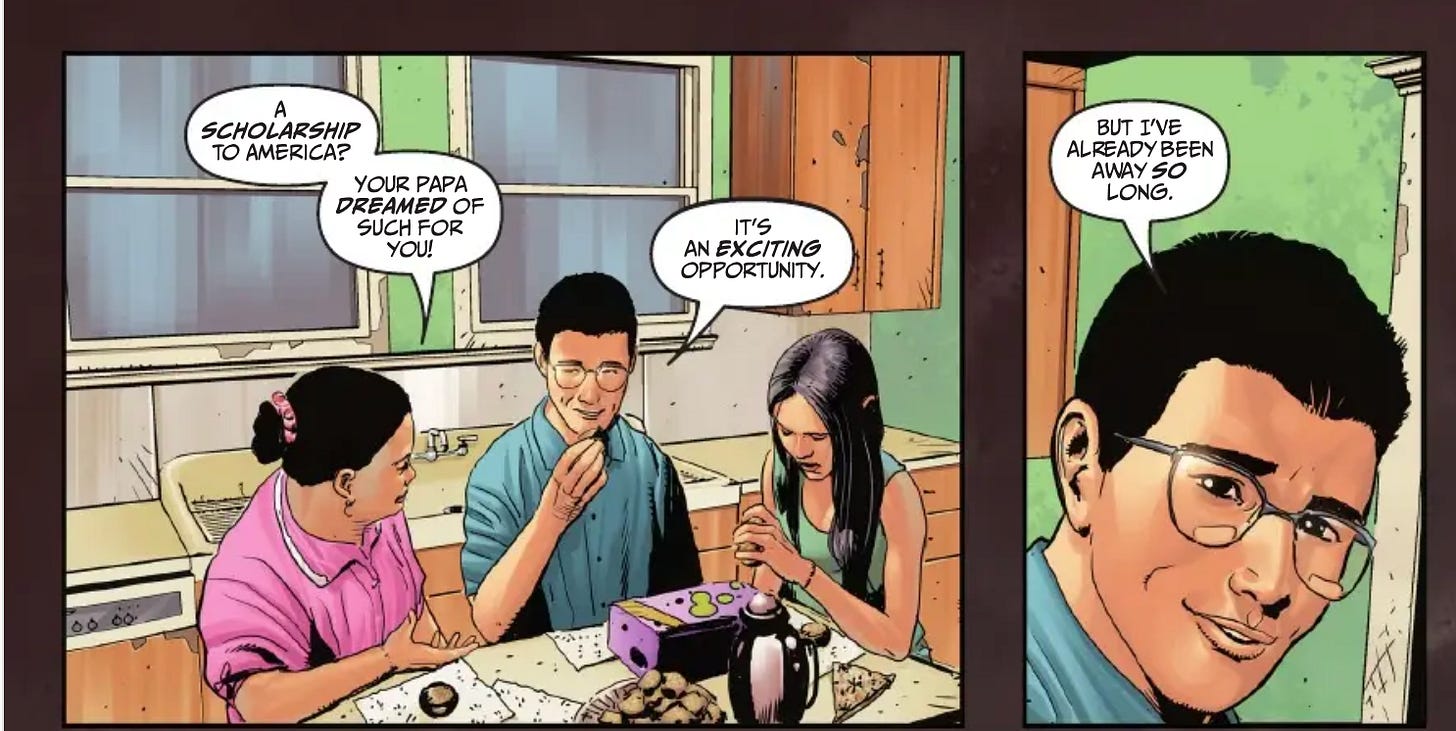

I mentioned in an earlier update how proud I was that one of the girls had not only used this time to teach herself English, but finish her high school curriculum on her own, and so successfully that she won a highly competitive scholarship to study at the American University of Afghanistan. It was founded in 2006, and moved its campus from Kabul to Qatar after the Taliban takeover. It began offering its curriculum online. Studying remotely at AUAF is one of the very few ways that an Afghan woman can still continue her education and receive an accredited degree.

She was thrilled. Her whole family was thrilled. I was thrilled. I was especially glad that she’d been recognized for she’d been able to achieve on her own, with no help from anyone. The girls haven’t seen the inside of a classroom since Kabul fell. Pakistan doesn’t let refugees use their schools. So the kids teach themselves from the Internet, despite levels of fear, uncertainty, and upheaval that would flatten most of us, and entirely without the daily structure of a school, teachers, or fellow students.

Ms S. tuned out the tumult and kept studying. She didn’t speak a word of English when we first met. Zip. To apply to the AUAF, she had to take an English exam and get through an English-language interview. Using only the English she’d taught herself on the Internet, she was not only admitted, she beat thousands of other candidates to win a full-tuition scholarship:

This was so important to her. First, it was a recognition of what she’d accomplished. But much more important, it meant she wouldn’t be idling. It’s awful to wait for asylum. JIAS, our sponsorship application holders, warned us that we should prepare ourselves for the long wait to be tough, emotionally. They were right. I can see it and hear it when I speak to them.

You’re in limbo. You’re neither one thing nor the other. For the kids, they’re watching year after year of their youth—their most productive years, the years they should be using to build a life—slip away. The sand slowly pours through the hourglass. The bureaucracies move like glaciers. None of it makes any sense. The whole world makes it clear that you’re unwanted—that it would be more convenient if you’d just die (so long as you don’t make a mess when you do—cleaning it up puts excess strain on local resources).

Winning this scholarship meant that even if the wait went on for another three years, she would arrive in Canada with an accredited university degree, which is not a mere practical or a professional asset to a young Afghan women, but a triumph over murderous obscurantism and barbarity.

Her whole family was so proud. We—our readers and I—helped them to buy her the new computer she needed to use Canvas and do her homework.

Yesterday, they told me that the scholarship had been rescinded. I hadn’t realized it was funded by USAID.

Those scholarships, by the way, didn’t cost the American taxpayer a penny. In 2018, USAID gave a US$50 million bequest to the Texas A&M University Foundation to create and administer the Women’s Scholarship Endowment program. It’s an investment pool, and the scholarship program ran exclusively on interest generated from the initial bequest, which remained untouched.

That interest paid for 208 scholarships—the last remaining hope for Afghan girls and women seeking higher education. Most of them went to young women who studied from the homes in which they’re now trapped in Afghanistan. The fund also paid for 120 women to relocate to Oman and Qatar to attend college in person, with living expenses covered.

On February 28, the students were abruptly informed their scholarships were ending and they would be sent back to Afghanistan within two weeks:

… These girls, who had transferred to the “Middle East College” in Muscat in late 2024 with the support of the Women’s Scholarship Foundation, said that due to the recent policy changes of the US government, their financial support has been cut, and they are now facing the threat of deportation.

In their letter, the students emphasized that if they are forced to return to Afghanistan, their lives and education would be at great risk due to the severe restrictions imposed by the Taliban on girls’ education and the security threats they would face. They urgently called for assistance from the US Embassy to find ways to ensure their safety and continue their education.

The State Department recently told the BBC that they would get a reprieve: Their funding would continue until June 30. But this won’t let any of the girls finish their degrees.

The program organizers are desperately searching for new funding (Hey, Qatar! Hey Oman! You’re not short of cash.)

Perhaps they’ll get it. Or perhaps they won’t.

Afghanistan was the third-largest beneficiary of USAID funding. More than 80 percent of the programs USAID funded have been cancelled. This has put an end to vaccination campaigns. Afghanistan is now facing a resurgence of measles, malaria, and polio. At least, I suppose, the world can’t say we are asking Afghan children to suffer something we wouldn’t ask our own to endure.

The WHO estimates that 1.84 million Afghans, mostly women and children, have been affected by the closure of 206 health centers funded by USAID. This is now an escalating humanitarian crisis. Nearly 220 more health facilities will be closed in the coming weeks.

… In some rural areas, these centers were the only means for the local population to access health services. Among the 206 closed health structures, 112 were dedicated to nutrition issues, 33 managed family care and 22 were devoted to very isolated areas. While men are also impacted by this lack of care, it primarily affects women and children, according to the WHO. The disappearance of maternal and child health services has already led to an increase in mortality, particularly in rural areas. …

Women are particularly suffering from the restrictions of American aid. These measures add to a radical policy imposed by the Taliban since their return to power in August 2021, depriving half of the population of freedom … “The medical centers are closing one after the other, the International Red Cross is gradually withdrawing from the country and Doctors Without Borders is sending more and more cases to us,” he said. “It's a nightmare, the country is a victim of a social femicide.”

Afghanistan is hardly the only country where the abrupt end to American aid is killing the poorest and most powerless people on earth. USAID provided 40 percent of all global foreign aid. Elon Musk locked USAID staff out of offices worldwide, left half a billion dollars of food aid rotting in ports and warehouses, ended lifesaving programs midstream. This has caused utter chaos in communities that depended on US-funded health clinics and food. At the time, there were warnings of famine, disease, and death. The warnings are coming true. It makes me physically ill to think that the American flag is now associated worldwide with such senseless, psychopathic cruelty.

We cut off programs providing food to children trapped in conflict zones. I’ve seen one after another story like this:

… Abdo starved to death in the weeks after President Trump froze all US foreign assistance, said local aid workers and a doctor. American-funded soup kitchens in Sudan, including the one near Abdo’s house, had been the only lifelines for tens of thousands of people besieged by fighting.

Bombs were falling. Gunfire was everywhere. Then, as the American money dried up, hundreds of soup kitchens closed in a matter of days.

The US$830 million we gave to Sudan in emergency aid fed 4.4 million Sudanese civilians. It was far more than anyone else was giving, but in the context of the US budget, it was nothing. Elon Musk’s net worth goes up by more every time he inhales. It is nothing to him. It was everything to the people we were feeding.

… Within days, over 300 soup kitchens run by Emergency Response Rooms, a network of democracy activists turned volunteer aid workers, were forced to close. In Jereif West, the neighborhood where Ms. Tariq works, hungry residents roved the streets in search of food amid shelling and drone strikes.

We also consigned people to this:

… From the pulpit, Reverend Billiance Chondwe counts the empty seats. “We are close to 300 [worshipers] but nowadays we are only less than 150. People are sick at home,” says Chondwe—or Pastor Billy as everyone calls him—as he greeted congregants on a Sunday in early April at the entrance to his church, the Somone Community Center, a branch of the Pentecostal Holiness Church in Zambia.

People are falling ill because the US-funded clinics where they got their HIV medications and care have suddenly been shuttered. The staff is gone. The electricity has been shut off. Some patients have already run out of their daily pills that keep HIV at bay—and they have started to feel the physical consequences of the virus surging back. …

Officials said that lifesaving aid—such as HIV medications—would continue to flow. But the reality on the ground shows otherwise. An untold number of people with HIV have simply and suddenly lost access to their medication.

It’s thought that PEPFAR has saved 25 million lives. Few things the United States has done have been more noble. The Lancet recently estimated that without PEPFAR, a million children who otherwise would not have been infected with HIV will be infected by 2030, and half a million children will die. Another 2.8 million children will be orphaned. The end of American aid in Africa is expected to result in the deaths of two to four million people who would not otherwise have died—every single year.

I’m certain there are vanishingly few American who would wish for this outcome. No one was clamoring for Elon Musk to end this program. Few Americans were even aware of it in the first place. (I say this based on anecdotal evidence: Whenever I mention PEPFAR to Americans, I get a blank look.) Even the Americans who bloviate on Twitter about never giving another penny to foreigners would be horrified if they truly grasped what Musk had done—if they understood what AIDS does to a human body; if they grasped that Africans were real, not figures of speech; if they knew what PEPFAR had achieved; if they knew it was fully within our power to let it continue, as everyone in Congress intended, and thereby prevent an unspeakable tragedy. Would they really say, “Let them die?” I can’t believe that. America may have changed a lot, but we can’t have changed that much. This program was our initiative, after all, only two decades ago.

But Americans don’t know. Many sincerely believe Musk put an end to a radical-left terrorist money-laundering scheme, and who wouldn’t want to end that? Or they pay no attention to the news at all. Africa, to most Americans, is as remote as Mars. They’ve never been there. The US media rarely reports the news from Africa. Perhaps it’s not surprising that few Americans have thought too much about what it means to “feed USAID to the wood chipper.”

Elon Musk grew up in South Africa, though. Sub-Saharan Africa isn’t an abstraction to him. He knows the people he’s sentenced to death are as real as he is. He knows exactly what HIV and AIDS did to Africa before PEPFAR. South Africa has the highest number of people infected with HIV of any country in the world.

Through PEPFAR, the US was holding AIDS at bay throughout the continent.

… Nozuko Ngcaweni, also a beneficiary of US aid, gets her HIV/AIDS drugs for treatment from the healthcare programs supported by USAID. “We are being killed in this manner [and] are going to die … You know, the day I heard that funding had stopped, I felt like I was dying.”

It would have been trivially easy for Musk to decide that Nozuko Ngcaweni should live. It just required him to leave well enough alone. No one would have criticized him for doing a poor job or thought less of him if he had spared PEPFAR. Not one person. It would not have harmed him or his enormous wealth. And it really was his decision, alone. Trump doesn’t pay the slightest bit of attention to anything that happens in Africa or the details of our federal budget. If Musk had told him PEPFAR was a terrific program, he would have believed it.

How does someone become a man who casually decides millions of innocent people, mostly women and children, should die? For no reason?

The line from Lear comes to mind—Is there any cause in nature that makes these hard hearts?

There is nothing wrong with saying that the United States should not have to pay for PEPFAR in perpetuity. But we didn’t plan to, and would not have had to. PEPFAR recipients in Africa had been gradually increasing their share of the financing. In 2004, Africans paid US$13.7 billion of the total costs per year; in 2021, they paid US$42.6 billion. In 2023, 59 percent of all HIV-related spending came from domestic resources, not PEPFAR. It was reasonable to expect many of these countries to take over completely by 2030.

National governments are now stepping up where they can. But the shortfall is overwhelming their health systems. No one saw this coming. Ministries can’t redistribute resources this quickly. Ending our funding this way, giving countries that are hardly blessed with an excess of state capacity no chance to plan for it, makes it far less likely that they will ever be able to take over the funding, because PEPFAR made a huge difference in their GDP growth. Children grew up with two parents; it made a huge difference to educational attainment. This is what allowed these countries to increase their share of the funding. PEPFAR had huge health spillover effects in every dimension: It reduced maternal mortality and raised rates of childhood immunization everywhere it operated. That is now going into reverse. Because of the way we’ve withdrawn our funding, these countries will be set back economically for years, which will affect everything they do—health, education, development, opportunity. What happens then? Mass migration: the very problem we’re now committing fresh outrages at home to combat. It’s senseless. It’s madness.

PEPFAR had direct economic benefits for the US, too, including a fourfold increase in US exports to the countries in question. It reduced migration. It increased our capacity to surveil and control every species of emerging infectious disease. It gave us influence in places where we’d had none before. We’ve lost all of that.

But they’ve lost more. If you can read this article through without wanting to vomit, more power to you:

… It’s now been eight days since both Dorcas and her mom, Theresa, took the last of their HIV medications. A single mom and an only child, they've always taken their medicine together at 8 pm each night. The change in routine has confused the little girl. … The doors of the clinic, which services over 2,000 HIV patients, have been locked since the end of January, the staff let go and the furniture largely removed. This clinic didn't just provide medication, it also provided basic food since HIV medicine cannot be taken on an empty stomach. Theresa and Dorcas lost both.

So far, without their medication, Theresa feels okay. But Dorcas has developed a fever and chills—and she feels weak. Flu-like symptoms are often one of the first symptoms after someone goes off HIV treatment—the level of virus rises and the body tries to fight it off. Worried, Theresa now stays home to tend to her daughter—who often rests on a mat by the tree outside their home. But it means Theresa isn't going house to house to do laundry and odd jobs, their main source of income.

… She thinks back to her two sisters who died of AIDS before medication became available—and free with help from the US. “I am now really worried,” she says looking at her daughter. “She’s a very jovial little girl, but she's been very miserable the past few days.”

Can you imagine how frightened this mother must be? She’s watched her two sisters die of this disease. She knows what awaits. AIDS is a terrible way to die, too. How do you decide to do this to desperately poor people? How could anyone be so carelessly cruel?

It’s not just human lives that will be lost. USAID was one of the world’s largest supporters of wildlife conservation. Its grants protected elephants in Tanzania, great apes in central Africa. Natural resources there will now be managed, in all likelihood, by organized crime and poachers. You will never convince me the country that mourned Harambe for weeks truly wanted this outcome. This is happening for no reason at all, which is the hardest thing to accept.

As for putting Americans first, we stranded American citizens who were working in dangerous places where they couldn’t even buy gas for their cars. Some escaped by fording rivers on foot with nothing but the clothes on their backs. We ignored signed contracts with them—and with their local partners.1 Everyone who signed a contract with the Americans will remember that. No one was given the chance to plan for anything.

It’s impossible for the programs we defunded to recover, even if someone else were willing to fund them. People have moved on, by necessity, to other jobs. Trust with local partners, sometimes built up over years or decades, is gone. European development agencies might have been able to replace some of this money, but they can’t, because they’re on a crash course to raise military spending. South Korea is replacing some of it. China is replacing some of it. But there’s no way to replace all of it. We were the most significant donor in the world, and what we did made a huge difference in a significant part of the world. It was exactly the part of the world that had made so much progress, in recent years, that until very recently it was plausible to imagine an end to absolute poverty in our lifetimes—and an end to the AIDS epidemic, too.

It is hardly as if we’re immune to the fallout. Uganda lost screenings for an outbreak of Sudan Virus. Human trafficking efforts have been crippled. We defunded a program to combat fentanyl-smuggling in Manzanillo port. What do you imagine the consequences of these decisions will be for Americans?

What do you imagine the impact of an uncontrolled AIDS epidemic will be? Viruses mutate. They cross borders. We were not funding these programs solely out of the goodness of our hearts.

Let me make a few points explicitly. First, I’m happy to concede that some USAID programs were wasteful. But USAID did not pay, as Karoline Leavitt cheerfully announced, “US$1.5 million to advance DEI in Serbia’s workplaces, US$70,000 for production of a DEI musical in Ireland, US$47,000 for a transgender opera in Colombia, US$32,000 for a transgender comic book in Peru.” That’s a lie.

USAID did support a program in Serbia focused on equal rights in the workplace for sexual minorities. It seems to me that money should have gone to people who needed it more. I don’t know what the thinking behind supporting this program was: Sometimes we do this sort of thing to support a political faction that’s friendlier to our interests. USAID did not fund any of the other programs on that list.

The State Department, not USAID, sponsored a concert by Irish and Irish-American musicians at the Royal Albert Hall in London. It was widely televised. You can watch it here:

The announcement for the event said it would “showcase the very best of American and Irish talent with a diverse program which aims to fulfill the US Embassy Dublin’s mission to promote diversity, inclusion, and equality.” (Of course it did: Just as everyone is now rushing to scrub those words from US government websites, everyone once tried, somehow, to fit them in.) The words were meaningless pap. We funded it, I’m sure, to promote the cultural ties between Ireland and America, to earn a bit of goodwill, and because it’s nice to have “Sponsored by the US Embassy” on the program when events like this are held.

As for whether the State Department should sponsor cultural events abroad, I suppose I’d agree that if we’re looking to cut inessential expenses, things like that could go. But it would look awful to be both the wealthiest country in the world and the only one that never sponsors anything. Every country’s embassy sponsors things. It’s part of diplomacy. That said, if the American people decide they don’t want to sponsor concerts anymore, no one will die as a result, and I doubt it would do severe harm to our relationships with countries like Ireland.

Likewise, the State Department made a small grant to an opera company in Colombia that once put on a production, by an American composer, featuring a transgender protagonist. Probably not my taste, but who knows. Maybe it’s a masterpiece. I haven’t listened to it. My argument about this is the same: It would look tacky if we were the only country that never did this sort of thing, but if we didn’t, no one would die.

There was no transgender comic book in Peru. The State Department funded this comic book to promote education and exchange programs in the US:

One of the characters in the second volume is gay. There’s not a word about transgenderism. Promoting American business and trade is one of the State Department’s responsibilities, and foreign students are a cash cow for the US, or they were. This seems a bit of a silly way to advertise American universities to me, but again, I’d want to ask the Embassy why they thought this was worth it before judging it. It didn’t have a thing to do with USAID.

But some USAID programs have indeed been genuinely wasteful. If you’ve studied the SIGAR reports, you know that some of our programs in Afghanistan amounted to throwing money in a furnace. The Tarakhil power plant, for example, commissioned in 2007, ran on diesel-fueled turbines, but Afghanistan didn’t have enough diesel to run it. USAID contributed funds to the building of an expensive road that was never completed. There are further examples. Our record of waste in Afghanistan was impressive, but USAID was no more guilty of waste than our other US agencies—it was certainly no more wasteful than the Defense Department.

I landed on one particularly egregious case of USAID fraud. It involved US$9 million in humanitarian aid designated for Syrian civilians. It wound up in the hands of al-Nusrah. According to the indictment:

USAID awarded US$122 million to NGO-1 between January 2015 through November 2018. That money was intended for food kits for conflict-affected Syrian refugees. Along with at least two co-conspirators, Al Hafyan directed food kits valued at millions of dollars to commanders leading ANF. ANF’s primary objective was the overthrow of the regime of Syrian President Bashar al Assad. ANF was notorious for the atrocities it committed and publicly took responsibility for conducting mass executions of civilians, suicide bombings, and kidnappings.

Al Hafyan sold the kits on the black market to the ANF commanders for his personal benefit. Al Hafyan and his coconspirators falsified beneficiary logs and inflated the number of food kits received by war-affected families in the Syrian villages of Bweiti, Lof, Mazratt-Shoukh, and Salamin to fraudulently make it appear that NGO-1 was dispersing the kits according to NGO-1’s guidelines.

But since this was one of the worst cases of fraud that USAID’s inspector general ever found, we shouldn’t imagine this was a common occurrence. Note, too, that we detected this fraud—through mechanisms we’d already established—and we indicted those responsible.

So yes, USAID has wasted taxpayer money. But reducing AIDS in Africa by 75 percent did not represent waste. It should not be difficult, conceptually, to grasp the difference between “an organization that has wasted money” and one that “only wastes money.” It requires deliberate obtuseness to misunderstand this.

Nor is it difficult to understand that in any large and ambitious venture, there will always be waste. This is likely a cost you just have to eat, because the alternative is excessive, self-defeating fear of waste. Musk is actually famous for grasping this principle. Unlike NASA—which is extremely cautious about failure because it fears the appearance of wasting taxpayer money—Musk is happy regularly to see his rockets blow up. If all we looked at were the blown-up rockets, though, we wouldn’t understand what SpaceX has achieved. This is also true of USAID.

Let me make a few points about what the US is and isn’t morally obliged to do. Moral philosophers make a distinction between what one must do and what goes beyond that obligation. You must refrain, for example, from murdering your neighbor. You are not obliged to help your neighbor pay his rent after he loses his job. The latter is a supererogatory act. Supererogatory acts go beyond what is necessary. Another course of action—involving less—would still be acceptable.

Opinions vary about whether charitable donations are supererogatory or obligatory. In some schools of thought, it’s supererogatory. But most religions view some level of charitable donation as obligatory and contributions in excess of this amount supererogatory. Moreover, few would deny that states have duties to their own citizens that they do not have to citizens of other countries. A government is obliged to provide for its own citizens in a way that would be supererogatory abroad.

In 2024, American spending amounted to 40 percent of global humanitarian aid even though its share of global GDP was only 26.11 percent. The EU, by contrast, was responsible for only 30.9 of humanitarian spending. We’ve unquestionably been bearing a larger burden than other countries.

I’ve always been exceedingly proud that the United States was the world’s largest humanitarian donor. I thought this made us a particularly noble country. Whether or not it served our interests—and it absolutely did—I wanted the United States to be known for vanquishing disease, squalor, and misery around the world. I truly think most Americans did, too. Throughout my life, I’ve heard Americans say, of programs like the Marshall Plan or PEPFAR, “No other country would do that.” It was not a criticism but a point of real pride. I suspect that until quite recently, Americans believed it was part of what made America exceptional. Great, even.

Leave aside, for a moment, the question of whether it is in our own interest to be the world’s largest donor of humanitarian aid. (It is very much in our interest, but this is a separate point.) I do not think we are under a moral obligation to contribute as disproportionately as we do. Doing so is supererogatory. We would not be villains if we reduced our aid spending. We’d just be a lot less exceptional and great.

But there is a very big difference between reducing aid spending—after public debate, through a constitutional process—and what we’ve done. The law speaks of reliance interests. (John buys paint and starts the renovation. Chuck cancels the project. John relied on Chuck’s promise and bought the paint; he therefore has a reliance interest in recovering the costs of the paint, which he incurred due to his reasonable reliance on Bob’s promise.) This legal principle reflects a widely-shared and intuitive moral judgment: Promises ought to be kept, and if you don’t keep yours, you are responsible for the trouble you’ve caused because other people trusted you.

We made promises. People were depending on us to fulfill them. Around the world, people and governments organized their lives in the expectation that we would honor our contracts and continue these programs without abruptly halting them with no warning. A small example of things people have done because they trusted us is the computer the S. Family purchased so that their daughter could go to school. A larger example is this one:

Brian Chiluba, 56, is comfortable at the top of a ladder and used to pushing a heavy wheelbarrow full of paint buckets around. He’s a house painter and—with the help of HIV medication, which he’s taken for 15 years—he always had the strength to do his work. But no longer. “I feel weakness—weak, weak, weak," he says as his voice cracks.

Since early February, when his local US-funded clinic shut down, he's struggled to get his medication. At first, he managed to obtain a few pills here and there but, now, he’s out entirely. Sitting on a wooden bench by the window with one of his three children nearby, he says he’s lost a lot of weight and feels like all the power has been drained out of him. Brian’s wife also has HIV and has run out of her medication, too. But, so far, she says she feels fine.

The couple went to a nearby government clinic hoping they would be able to get their medications refilled. But, they say, they were told they must bring their medical records in order to register as new patients. So they’ve been going back to their old clinic to get their files. Every time they go, it’s still shuttered. And yet, he says, they have no choice but to keep trying. “We need to wait until there’s someone at the USAID facility,” he says. … Brian worries that by the time he gets his medical record and registers at a new clinic, it will be too late. “I’m going to lose my life, and I will leave my children suffering.”

I accept that we did not owe Brian Chiluba HIV medication in perpetuity. To give that to him would have been a supererogatory act. But we sure as hell owe him his medical records. We owed him the time he and his government needed to plan for this, to reallocate resources and develop policies to prevent him from dying so pointlessly. We owed this to his children, too.

As for me, I think giving aid, in massive amounts, is an easy call. We should give it because we’re rich and powerful, and the people receiving it are not, and the difference between being born in Palo Alto and being born in Zambia is luck. I think we should give it because we’re a country with a Christian culture, and even those who have no idea where the sentiment comes from have an inkling that Brian Chiluba, too, was made in the image of God. That you should feed the hungry and heal the sick. I think we should do it because the amount of money in question is a minuscule fraction of our budget, and not one of us will feel the difference if we don’t. I think we should do it because you should do unto others what you’d have them do to you, and If I were Brian Chiluba, I’d want us to give him his medical records.

I think we should do it because there’s a nineteen-year-old college student in South Africa who was born with HIV but who, thanks to PEPFAR, looked forward to a long life full of everything college students looked forward to. Now, she is going to die, and she knows it, and she is terrified. Frankly, I can’t really think of much I’d rather do with my money than spare her that fate. But if other Americans say, “I don’t want to help,” they’re not wicked. They are not obliged to help. Helping is supererogatory. They are, however, obliged to keep their promises. That is obligatory. What Elon Musk has done is wicked, and so is supporting it.

It is especially grotesque that Trump, apparently, is deeply concerned about human rights in South Africa owing to its new land reform bill, which Trump believes to be racist (and which is probably a bad idea, but not racist). He is so concerned that we’ve offered white South Africans asylum even though we’re refusing it to everyone else in the world—including Afghan allies already in America—and even though they don’t want it. Other South Africans may be forgiven for drawing uncharitable conclusions about why we’re making a song and dance about that while precipitously withdrawing the HIV medication that keeps so many South Africans alive.

… Tshabalala said the consequences of Trump’s actions will be devastating. “While the Trump administration is fighting for a land bill that has nothing to do with them and making noise about human rights violations, they are inadvertently committing genocide that will be remembered for years to come.”

She’s wrong to say we’re committing genocide inadvertently. First, you can’t commit genocide inadvertently because you can’t commit murder inadvertently. If you kill someone inadvertently, it isn’t murder. Murder requires a mens rea. (It might be negligent homicide, or manslaughter.)

Nor is declining to save someone’s life the same as murdering them (although in some cases it is judged to be depraved-heart murder). One is obliged not to kill, but saving a life is generally held to be supererogatory—hence thou shalt not kill; but needst not strive/ Officiously to keep alive.

So no, this isn’t genocide. South Africa’s case against Israel suggests that the formal definition of genocide may not be widely understood there. But I do not mean to criticize Tshabalala: She has more to worry about right now than finding le mot juste to describe our policy, and I understand what she meant. I have no doubt she’s right to say this will be remembered for years to come.

I don’t know what’s in Elon Musk’s heart, so I don’t know whether he’s doing this “inadvertently.” If he’s done this on purpose, because he wants these people to die, it is obviously depraved—it is one of the most depraved acts in American history. If he’s done it inadvertently, it is also depraved, but in a different way.

I’m not sure what, exactly, is the right word for the crime of allowing millions of people to die because we let a neurotic, drug-addled oligarch—and teenagers with names like “Big Balls”—run our government and destroy whatever they felt like destroying. Perhaps “crime against humanity” best captures it. This phrase, too, has a specific meaning under international law (and it isn’t this). But the phrase seems right. It is an obvious moral crime. Humanity is the victim—theirs and ours. So perhaps those are les mots justes.

Atul Gawande lived down the hall from me when I was in college, though I didn’t know him well. He went on to have an unusually distinguished medical career, later becoming the assistant administrator for the Bureau of Global Health at the USAID under Biden. Please listen to this interview with him—the whole thing—or read the transcript:

… The internal estimates are that more than a hundred and sixty thousand people will die from malaria per year, from the abandonment of these programs, if they’re not restored. We’re talking about twenty million people dependent on HIV medicines—and you have to calculate how many you think will get back on, and how many will die in a year. But you’re talking hundreds of thousands in Year One at a minimum. But then on the immunization side, you’re talking about more than a million estimated deaths.

… This damage has created effects that will be forever. Let’s say they turned everything back on again, and said, “Whoops, I’m sorry.” I had a discussion with a minister of health just today, and he said, “I’ve never been treated so much like a second-class human being.” He was so grateful for what America did. “And for decades, America was there. I never imagined America could be indifferent, could simply abandon people in the midst of treatments, in the midst of clinical trials, in the midst of partnership—and not even talk to me, not even have a discussion so that we could plan together: OK, you are going to have big cuts to make. We will work together and figure out how to solve it.”

That’s not what happened. He will never trust the US again. We are entering a different state of relations. We are seeing lots of other countries stand up around the world—our friends, Canada, Mexico. But African countries, too, Europe. Everybody’s taking on the lesson that America cannot be trusted. That has enormous costs.

It’s tragic and outrageous, no?

That is beautifully put. What I say is—I’m a little stronger. It’s shameful and evil.

That Elon Musk willed this to happen made me grasp, really for the first time, what Hannah Arendt meant in observing that evil is shockingly banal. (Stupid and self-pitying, too.) How can one man—such a nothing, such a fundamentally trivial person—be responsible for so much suffering? Is it possible that he truly doesn’t realize what he’s done?

Watch this interview with Atul Gawande, too. It’s a good use of your time:

What I’ve written here barely scratches the surface of the humanitarian consequences of Musk’s rampage through the government. The strategic consequences are, if anything, worse. As the former head of USAID said, “When you pull all of that out, you send some very dangerous messages. The US is signaling that we don’t care whether people live or die and that we’re not a reliable partner.” He’s right.

Little that China is doing now will help the people we’ve abandoned. But they are nonetheless making the most of it. We will pay for this dearly—and for a very long time.

You’ve just read what was meant to be the introduction to the essay you asked for, the one exploring the way China is exploiting our withdrawal from the world. But that will be in the next newsletter. On writing this, I decided the topic deserved to be more than a brief introduction. So I’ll send that separately. (It really won’t take more than a day, this time. It’s written already. I just got sidetracked when I heard about Ms. S’s scholarship.)

Contract law is the foundation of prosperity and the reason we’re in a position to give aid in the first place.

In all the dark chapters of American governance, few administrations have matched the sheer vileness of Donald Trump's. It is a vileness not of accident, but of design — proudly worn, aggressively sold, and methodically implemented. Nowhere is this clearer than in the administration’s systematic attack on the vulnerable, both abroad and at home.

The cuts to USAID represent more than just another budgetary footnote. They are a slow-motion demolition of the very instruments that once made America respected across continents: food aid, disaster relief, education initiatives, and public health support. These programs were not acts of charity; they were investments in human dignity and global stability, paying dividends in goodwill and influence. Slashing them is a self-inflicted wound, a public burning of the American brand for the cheap applause of a few isolationist ideologues.

But the cruelty does not end at the water’s edge. The Trump administration’s war on the poor, the sick, and the marginalized at home is just as savage. Cuts to Medicaid, rollbacks of nutritional aid, assaults on civil rights protections — these are not policy errors. They are policy goals. The administration’s America First agenda has always meant America’s Most Vulnerable Last.

Among the rising chorus of Trumpian apologists, few embody the grotesque spirit of this movement more purely than Karoline Leavitt. Leavitt, a former press staffer now reborn as a public face of MAGA grievance, operates less as a political figure and more as a caricature — the AI-generated avatar of grievance politics. Her style is a mixture of self-righteous ignorance and militant disinformation, reciting propaganda with the zeal of a 21st-century fascist-in-training. If one were to design a junior spokesperson for authoritarianism, it would look and sound very much like her.

Have you tried reaching out to David Frum at all (about the family I mean)? He’s Canadian American as you probably know, and his mother was a pretty prominent media figure in Canada for many years. So it might be possible he may know a few people in high places over there.