From Claire—I wrote this essay five years ago. Longtime readers of this newsletter may remember it. I was reminded of it this morning when I read this article by Françoise Thom: Melancholic reflections on the French elections. When I went back to read it, I saw that it held up well.

Beyond Left and Right

The New Caesarism tends to overlap with, although it is not identical to, what is often described as the far right. Because the term is in such wide use, I will use it too, but I point out that like “democracy,” it is a phrase that showcases the diminishment of our political vocabulary and with it, our ability to think usefully about politics. “I wish media outlets would stop referring to [Austria’s] FPO as a ‘populist, far-right’ party,” lamented an Austrian of Libyan descent. “They need to be called out for what they really are: a vicious, racist organisation that preys on the most vulnerable in society under the guise of patriotism.” That description conveys more information than “populist, far-right,” but there’s more to it.

A more accurate description of “far-right, populist” movements would involve all of the following ideas.

First, its adherents embrace the besieged fortress narrative. The people or the country is a besieged fortress, threatened internally by elites, minorities and traitors, and externally by hostile foreign powers and spies. These enemies seek to thwart the People’s Will and deny the nation its rightful place in the world.

Second, phrases such as “the people’s will” dominate public discourse. A key concept. A useful way to understand it is in terms of the philosophical contest between Rousseau and Montesquieu. Illiberal democracy is justified by what Rousseau esteemed as the volonté generale, or the will of the people as a whole:

As long as several men assembled together consider themselves as a single body, they have only one will which is directed towards their common preservation and general well-being. Then, all the animating forces of the state are vigorous and simple, and its principles are clear and luminous; it has no incompatible or conflicting interests; the common good makes itself so manifestly evident that only common sense is needed to discern it. Peace, unity and equality are the enemies of political sophistication. Upright and simple men are difficult to deceive precisely because of their simplicity; stratagems and clever arguments do not prevail upon them, they are not indeed subtle enough to be dupes. When we see among the happiest people in the world bands of peasants regulating the affairs of state under an oak tree, and always acting wisely, can we help feeling a certain contempt for the refinements of other nations, which employ so much skill and effort to make themselves at once illustrious and wretched?

A state thus governed needs very few laws.1

Rousseau’s vision is antithetical to the principle dear to Montesquieu: the rule of law, known in connection with Montesquieu’s insistence on the separation of powers—particularly the separation of judicial power from executive and legislative authority. Montesquieu’s thought had a profound effect on the American founding, and particularly on James Madison. “[T]he preservation of liberty,” Madison wrote in Federalist 47, “requires that the three great departments of power should be separate and distinct.”

The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny. [My emphasis.] … The oracle who is always consulted and cited on this subject is the celebrated Montesquieu. If he be not the author of this invaluable precept in the science of politics, he has the merit at least of displaying and recommending it most effectually to the attention of mankind.

The far-right—and New Caesars of all stripes—do not object to democracy . They object to liberalism, which they correctly believe to be in tension with democracy, not indivisible from it. They view liberal traditions and institutions as obstacles to pure democracy: They will argue, for example, that independent courts prevent the implementation of the people’s will; that the protection of the rights of minorities runs contrary to the majority’s legitimate and well-founded contempt or fear of these minorities; that property rights and free markets create disproportionally powerful and wealthy elites, both to the majority’s detriment and against its will; that a free press is undemocratic because it is too readily captured by elites, whose interests—not the people’s—this press then serves. They object, too, to the inherent inefficiency of liberal institutions: Checks and balances on power prevent the implementation of the people’s will, reducing government to a fractious talking shop that cannot redress their legitimate grievances.

Readers acquainted with the history of the 1930s will recall that these arguments were advanced throughout Europe by fascist politicians and movements, and particularly by Hitler. These are old complaints about liberal democracy. They have enduring appeal, because they are true. They are true by design: Inefficiency is the price of the separation of powers. Liberals such as those who founded the United States perfectly understood the tension between democracy and liberalism; they saw constitutional governance as proof against an excess of democracy, which they viewed—with horror—as rule by the mob.

The distinction has been known and recognized since Hellenistic Greece. Polybius, for example, upon whom Montesquieu greatly relied, drew a distinction between the demos and the ochlos. Both were systems such that power was vested in the people, but in the former, the people were constrained by legal framework, and they were educated, knowledgeable, informed, and deliberative. In the latter, the people were lawless, a mobile vulgus: a stupid and emotional mob. Needless to say, the Greeks thought the former good and the latter bad—except that it isn’t needless to say: If it were, we wouldn’t be on the verge of ochlocracy.

That these principles are genuinely, deeply in tension has become obscure to many Americans through a process of collective loss of historic memory and the muddled use of language. We’ve so long used “democracy” as a word that compasses both the will of the people and the rule of law that we’ve forgotten what used to be obvious: They are not the same thing.

In far-right movements—and far-left ones, for that matter—Rousseau’s vision has triumphed.2 Leaders present themselves as a conduit of the volonté generale. The leader is often held to have near-magical gifts: The New Caesar—and only the New Caesar —is capable of discerning and channelling the volonté generale with unerring fidelity (“I am your voice”). The New Caesar —and only the New Caesar —is capable of delivering the authentic people from their enemies, the elites, and the dark future they face. (“I alone can fix it.”)

The idea of an authentic people, too, is key. If you find to your dismay that your will has not been properly channelled by the leader, this proves that you are not authentically of the people. You are an elite—or some other kind of enemy. This understanding of the relationship between the authentic people and their providential conduit is described in the literature as “populism.” Nota bene: Populism is one aspect, but not the sole aspect, of such movements. It is a very important one, though.

“They say we are violating norms of international law. [but] almost 92 percent of our people support Crimea’s reunification with Russia. …Now this is a matter for Russia’s own political decision, and any decision here can be based only on the people’s will, because the people is the ultimate source of all authority.” –Putin

“This is how it is: there is a Soros plan. It comprises four points. He wrote it down himself, the Soros Empire published it and began recruitment for implementation of the plan. The plan says that every year hundreds of thousands migrants – and, if possible, a million – should be brought into the territory of the European Union from the Muslim world. … in Brussels an alliance has been forged against the will of the people. The members of this alliance are the Brussels bureaucrats and their political elite, and the system that may be described as the Soros Empire. This is an alliance which has been forged against the European people. … As usual, when the leaders—when the members of the great political elite—turn against their own people, there is always a need for inquisitors to launch proceedings against those who voice the will of the people. … Europe is currently being prepared to hand its territory over to a new mixed, Islamised Europe. We are observing the conscious step-by-step implementation of this policy. … . We shouldn’t forget that Hungary …. stopped the migrant invasion flooding into Europe. … for as long as I am the Prime Minister of Hungary, at the head of the Fidesz and Christian Democratic government, the border fence will remain in place and we shall protect our borders. And in doing so we shall also protect Europe. In contrast to this, the opposition in Hungary openly states that they’ll dismantle the fence and let immigrants into the country … they’re ready to consign Europe to a new European future with a mixed population. [But] this time our real opponents will not be the domestic opposition parties. Everyone can see that in recent years a strong and determined unity on national affairs has been forged; in the sophisticated language of politics, we’ve called it the “central field of power.” The opposition parties don’t know how to cope with this field of power, with this national unity. In the campaign facing us we’ll primarily have to stand our ground against external forces: in the next nine months we’ll have to stand our ground against Soros’s mafia network and the Brussels bureaucrats, and the media operated by them. –Orbàn

“We are the people. Who are you?” –Erdoğan

“The only important thing is the unification of the people – because the other people don’t mean anything.” –Trump

“The people’s will is clearly emerging and challenging either supranational political powers such as the EU, or big financial powers, against a system which, for too many years, has been defending specific interests and no longer defends the interests of people.” –Marine Le Pen

“A victory for real people.” –Nigel Farage

“These [enemies of the people] have always scorned this nation. These [enemies of the people] always scorned the will of the people and their choices. –Erdoğan

“You have the haute volée [high society] behind you; I have the people with me.” –Norbert Hofer (of Austria’s FPO)

“The FAKE NEWS media (failing @nytimes, @NBCNews, @ABC, @CBS, @CNN) is not my enemy, it is the enemy of the American People! Sick!” – Trump.

“What does my people want? The death penalty!” –Erdoğan.

Far-right populist movements embrace specific theories about trade and immigrants, respectively. Their theories are a response to real problems that liberal democracies have not yet been able to solve. It is a reality that globalization has created winners and losers, a reality that many of the losers have not been compensated for their loss, and a reality that this has created enormous social dislocation. Mainstream politicians have broadly proposed two solutions to this: Compensating the losers, or telling them, tough, but that’s just the way it is. These are in fact the only possible solutions. Far-right movements campaign on the promise to end globalization—usually promising to erect trade barriers or withdraw from regional and international trade associations such as NAFTA or the European Union. Their proposals are nonsensical because there is in fact no way to end globalization. Notably, these parties do not tend to cut their countries off from the international economy once they gain power. They cannot, as we shall see, because integration into the international economy is integral to the way they keep power.

Likewise, their theories about immigration are a response to a real problem. It is a reality that the demography of developed countries, characterized by longer life spans and our tendency to have fewer children, makes traditional welfare models unsustainable. Mainstream politicians have offered two solutions to this: reducing welfare spending or enlarging immigration. These are in fact the only possible solutions. Far-right movements instead propose to protect welfare spending by excluding immigrants, whom they cast as undeserving and not authentically part of the people. They suggest they will by means of magic boost the birth rate. Again these ideas are nonsensical: The reality, given the underlying demographic problem, is that these newcomers are not a drain to the welfare system but a requirement to sustain it, and no far-right party in power, so far, has had any success in boosting the birth rate.

From the above, we see that “far-right” is an inadequate and even a misleading term. The implication of the phrase is that such figures as Marine Le Pen and Geert Wilders simply hold a more passionate version of traditional right-wing views. This is clearly not so. Their ideology is something sui generis, and it is philosophically incompatible with core values of the West’s traditional right-wing parties.

Our ideas of “left” and “right” reflect the 20th century’s great debates about the merits of redistributive social and economic policies, private property, and capitalism. But the war now underway for the world’s soul is not between the right and the left. These categories are a distraction. Mainstream left and right parties in Europe and the United States are not greatly different in their economic philosophy or policy proposals, despite the passionately-held public belief that they are. We have converged on a consensus that the economy must be mixed; we are haggling about what parts of it to mix and how best to mix them. Our hysterical obsession with an imaginary left-right cleavage has rendered us oblivious to the real divide—between liberalism and illiberalism.

Nor can the far-right even be located on the original left-right spectrum, dating from the French Revolution, when monarchists sat to the president’s right in the National Assembly and revolutionaries to his left. Apart from a few odd lunatics with no political appeal, there is no call on the far-right for monarchy or revolution. They have fully accepted democracy as the only game in town, the only legitimate form of governance. In so far as they embrace democracy enthusiastically, these movements cannot properly be called Nazi or fascist movements, either—even if some of their ideas have clearly been inherited from them.

Nor does the far-right hold a monopoly on the West’s growing illiberalism. This last is a key point, for failure to understand it will mean the failure of efforts to protect liberal democracy. Illiberalism is also characteristic of growingly popular far-left movements—and Islamist movements—throughout the West. In their rejection of liberalism, these movements have more in common with far-right parties than they do the mainstream left and right. All criticize liberalism in on similar grounds, and often in similar terms. Far right and Islamist movements denigrate liberalism for undermining moral values, religious belief, and patriotism; far left movements attack it as a cynical camouflage for economic exploitation and the cause of economic disparity. What distinguishes these movements is less important than what unites them. What unites them is their hostility to liberalism.

There are other characteristics shared by these movements. They tend to be shot through with what Kierkegaard called ressentiment—a sense of inferiority or failure, reassigned to an external scapegoat. (Trump’s supporters almost perfectly embody this; they seem to have walked off the pages of Nietzsche.) The New Caesars are prone to suggesting that if voters are economically frustrated, it’s because the Establishment—be it the Acela corridor or the Eurostar corridor—is comprised of a bunch of Davos-brained elitists who have determined to rip them off, permit them to be ripped off, or destroy their “sovereignty.” Everywhere these movements rely upon the idea of an ordinary, common man whose misfortunes are not that—misfortune—but the consequence of an elite that has taken them for a ride, bamboozled, and humiliated them. The “elites” vary in the story from country to country, but corporate elites, finance capital, and Jews tend to feature large, as do academics and journalists.

Liberal democracy’s defenders must understand that this ressentiment can never be redressed or satisfied, so there is no point in trying. Erdoğan, for example, now has near-absolute power in Turkey. The despised elite against which he has been campaigning for decades has either been completely co-opted or is languishing in jail. But his rhetoric is unchanged, and his supporters still believe they are humble, scorned, and powerless victims—rather than the overwhelmingly powerful majority that has controlled the country for as long as many of them have been alive.

Antisemitism has, historically, been coupled with ressentiment, and unsurprisingly, these movements too tend to flirt with it or embrace it warmly. This has been accompanied by the growth, both in Europe and the United States, of an ideology we might call pseudo-antisemitism: a set of beliefs that evoke the worldview of traditional European antisemites, yet make no reference to Jews. What could this possibly mean? It means that people have learned there are things one must not say or think about Jews, and that thinking or saying those things is wrong and wicked.

That is good, by the way. It is an improvement. But it also means that many people haven’t thought deeply about why it is wrong to speak this way of Jews. They have learned the lesson that Jews, per se, should not be the object of a certain system of thought, or habit of the mind. But they haven’t learned to recognize and repudiate the whole system of thought. The system of thought is familiar to anyone who’s studied Nazi propaganda: There is an obsessive dwelling on “rootless cosmopolitans,” bankers, elites, and the media, on people who are not properly part of the nation and the soil, but instead loyal to some kind of occult international force.

It is a dangerous system of thought, even if Jews are no longer at the heart of the obsession. In the first place, it is incorrect: it misrepresents the way the world works. People who are deeply confused about how things work are prone to making terrible errors. Second, someone will obviously wind up, in this scenario, playing the role of the Jews.

There was more than a hint of it, for example, in Theresa May’s dictum: “If you believe you are a citizen of the world, you’re a citizen of nowhere.” Had she colored the comment with the word that usually accompanies this sentiment–Jew–her remarks would have been recognized, immediately, as something straight from The Protocols of the Elders of Zion; it was redolent of the German anti-Semitic discourse that emerged in the 19th century, with the “rootless Jew” in the role of the “cosmopolitan” citizen from “nowhere.” Yet it would be absurd to imagine that Theresa May is an antisemite. Since she clearly is not, the comment simply made people queasy, for reasons they couldn’t quite place.

But they are queasy for a good reason. May repudiated the Enlightenment. Cosmopolitanism is one of the highest ideals of Enlightenment philosophy; it was Immanuel Kant who proposed the ideal of world citizenship as a means to achieve perpetual peace. That we are now casually disparaging Enlightenment ideals—that we don’t even know what those ideals were—is sinister. The return of anti-Semitism in the West should concern us in its own right, but so should this form of pseudo-anti-Semitism. Where it emerges, Caesarism is not far behind.

Connected to anti-cosmopolitanism is an obsession with an incoherent notion of sovereignty. Both the use of the term “globalism” as an epithet and this esteem for an unattainable and undesirable form of “sovereignty” have their origins in Russian propaganda. The argument, loosely, is that all traditional tools of post-Westphalian statecraft short of war are an infringement on “sovereignty.”

Of course this is ludicrous. It is true in a trivial sense that treaties and agreements among nations represent commitments, on both sides, not to do whatever the hell they please. This is a good thing. If the logic of the anti-sovereignty argument is followed to its natural end, there can be no cooperation among nations. All treaties, international agreements, and conventions on cooperation are infringements upon “sovereignty.”

It is particularly important to understand the reaction of illiberal politicians to the refugee crisis in this light. In the anti-liberal view, Angela Merkel was deforming the sovereignty of European nations by insisting they uphold the treaties to which they were signatory—to wit, the Geneva Conventions. In Merkel’s view, she was upholding the law.

This deformed notion of sovereignty is (not coincidentally) extremely useful to the Kremlin, which styles itself as a beacon of pure sovereignty in a world otherwise subordinated and enslaved to America. The Kremlin media supports and encourages Scottish and Catalan separatism, Brexit, opposition to trans-Atlantic trade, Le Pen, Orbán, and any like cause with repetitive blandishments about “sovereignty.” It is of course only Moscow’s sovereignty with which they are genuinely preoccupied; the Kremlin envisions establishing its own sovereignty over a fractured West.

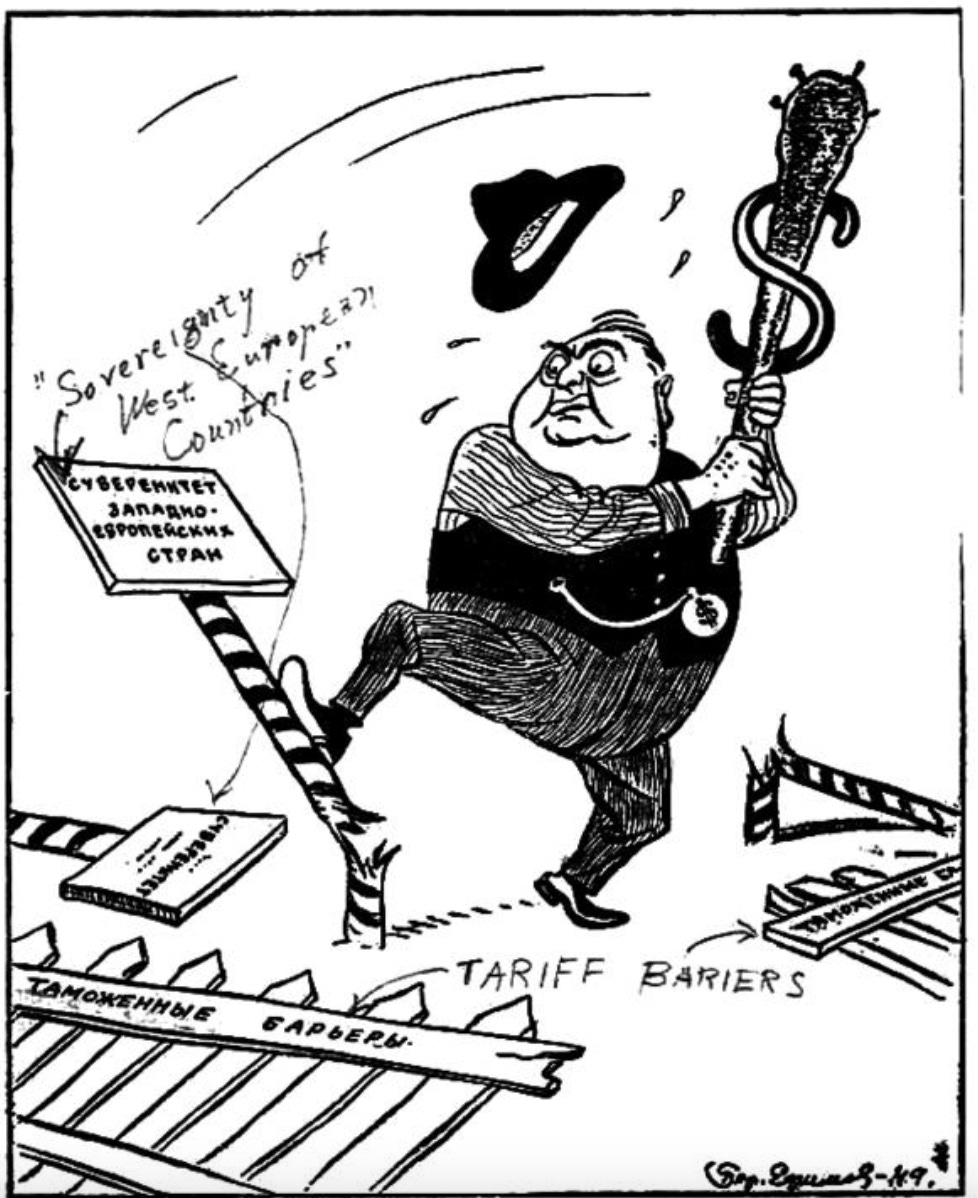

The promotion of this preposterous conception of sovereignty is certainly not a recent Kremlin innovation. This has very old roots. In 1949, Paul Hoffman, then head of the Economic Cooperation Administration, or ECA, addressed the nations of the Council of the European Economic Cooperation Association and sketched out a plan for the creation of a united western European market with no customs barriers or tariffs. The ECA enthusiastically adopted the idea, laying the foundation for the European Economic Community and later the European Union.

Precisely because the idea would clearly strengthen and unite the West under the United States’ aegis, the Soviet Union’s propaganda organs went into overdrive to combat it. Communist criticism of the Marshall plan was uncannily similar to the language now used by UKIP and the National Front to criticize the European Union, and indeed by people who support these parties and movements in America—even though many such movements are intrinsically hostile to the United States. In 1949, the French paper L'Humanité, for example, like many other communist publications, wrote, “After disorganizing the national economies of the countries which are under the American yoke, American leaders now intend conclusively to subjugate the economy of these countries to their own interests.”

Below is a cartoon from the Soviet paper Izvestiya. Hoffman, depicted as a fat capitalist, is purported to be attacking “the sovereignty” of the Marshall Plan countries. The idea that the “sovereignty” of European countries was undermined by economic cooperation and low tariffs is nonsensical. Moscow was clearly the source of this idea, Moscow remains the source of this idea, and Moscow’s motives for promoting it—then and now—are entirely cynical:

Thus it was astonishing to hear Steve Bannon take up these themes, verbatim, in the year 2017. When asked, for example, about the ties between UKIP, the National Front, and the Kremlin—and the propensity of these parties to “strongly [defend] Russian positions in geopolitical terms”—Bannon replied,

One of the reasons is that they believe that at least Putin is standing up for traditional institutions, and he’s trying to do it in a form of nationalism — and I think that people, particularly in certain countries, want to see the sovereignty for their country, they want to see nationalism for their country. They don’t believe in this kind of pan-European Union or they don’t believe in the centralized government in the United States … we the Judeo-Christian West really have to look at what he’s talking about as far as traditionalism goes — particularly the sense of where it supports the underpinnings of nationalism — and I happen to think that the individual sovereignty of a country is a good thing and a strong thing. I think strong countries and strong nationalist movements in countries make strong neighbors, and that is really the building blocks that built Western Europe and the United States, and I think it’s what can see us forward.

To say, in the context of Europe, that “strong nationalist movements in countries make strong neighbors” is to express a view that is not just ignorant of history, but directly contrary to it, which is no small achievement. “Strong nationalist movements” in Europe have turned Europe into an abattoir, each outbreak of the disease bloodier and more devastating than the one before. Here is succinct description of the results:

Two hundred and thirty-one million men, women, and children died violently in the twentieth century, shot over open pits, murdered in secret police cellars, asphyxiated in Nazi gas ovens, worked to death in Arctic mines or timber camps, the victims of deliberately contrived famines or lunatic industrial experiments, whole populations ravaged by alien armies, bombed to smithereens, or sent to wander in their exiled millions across all the violated borders of Europe and Asia. …

At the end of The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, A. J. P. Taylor remarked of the period between the Congress of Berlin in 1878 and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 that “Europe had never known such peace and tranquillity since the age of the Antonines.”

One would never have imagined in the nineteenth century that the world could spare so much blood or that it would have conceived the desire to shed it.

No one who has taken an introductory survey course in European history could fail to know this, and surely Bannon does know it. So what on earth is he saying—and why?

Either Bannon knows nothing about American and European history, or he is confident that his audience knows nothing about it. Bannon is widely reported to keep books about history strewn on his desk. Presumably he has at least read the cover flaps. This suggests that the correct hypothesis is the latter.

Unfortunately, evidence suggests his confidence in his audience’s ignorance is not misplaced. Our wider public knows nothing about American or European history. This has rendered us intellectually defenseless against propagandists, cranks, and charlatans who blithely endorse the worst ideas in history—some in the full knowledge that embracing them will destroy us.

Illiberal Democracy as an Ideology

Let us say a bit more about what the New Caesars believe. Their fascist forebears (and their communist ones, and their monarchist ones) disdained elections. The New Caesars do not. To the contrary, they love them, and often transform the system as much as they can to a plebiscitary rather than a representative democracy. They are particularly fond of referenda, which they often use to enact sweeping constitutional change, sometimes under the cover of a bundle of clauses that include popular handouts and thus obscure the poison pill.3 When critics attack such politicians as undemocratic, they are wrong, and dangerously so, because they have failed to grasp what is really going on. The carelessness with which we’ve come to use language has caused us to be unable to appreciate essential aspects of their ideology and thus their appeal; it has caused us to misunderstand how such regimes rise and to power and keep it.

The New Caesar’s legitimacy devolves—entirely—from victory at the polls. But this victory is not understood as it would be in a liberal democracy. It is understood as a comprehensive mandate for any and all of the New Caesar’s policies, without limits. Those who challenge their policies are not viewed, as they would be in a liberal democracy, as the loyal opposition; nor is a robust opposition viewed as an integral, necessary aspect of a healthy democracy. Opponents are viewed as enemies of the will of the people—that is to say, one step short of outright traitors.

Illiberal democrats do not see themselves as “undemocratic.” They see themselves as more democratic. They believe their form of democracy is a truer fulfilment of the democratic ideal than the liberal version. Putin explained this clearly when challenged, in 2006, by an American journalist about his “respect for democracy.”

I would first ask these people how they understand the concept of democracy. This is a philosophical question, after all, and there is no one clear answer to it. In your country, what is democracy in the direct sense of the term? Democracy is the rule of the people. But what does the rule of the people mean in the modern world, in a huge, multi-ethnic and multi-religious state? In older days in some parts of the world, in the city states of ancient Greece, for example, or in the Republic of Novgorod (there used to be such a state on the territory of what is now the Russian Federation) the people would gather in the city square and vote directly. This was direct democracy in the most direct sense of the word. But what is democracy in a modern state with a population of millions? In your country, the United States, the president is elected not through direct secret ballot but through a system of electoral colleges. Here in Russia, the president is elected through direct secret ballot by the entire population of the Russian Federation. So whose system is more democratic when it comes to deciding this crucial issue of power, yours or ours? This is a question to which our critics cannot give a direct answer.

We can give a direct answer, as it happens. Russia’s system is more democratic—if by democracy, you mean “direct secret ballot,” and if you don’t ask what happens to rivals who might win that ballot. As Madison understood, it is entirely possible to be a democracy that meets “the very definition of tyranny.”

It is tempting, but wrong, to see nothing ideologically coherent in illiberal democracy—to dismiss it as a cover for kleptocracy, or see it as a stage on the road to, or away from, liberal democracy. Such countries are often described in the media, for example, as “on the path to democracy,” or suffering from “democratic backsliding”—both phrases suggesting that we are looking at a fledgling or failed form of liberal democracy.

We are not. We are looking at regimes that are the authentic fulfillment, the end point, of a distinct ideology. That ideology is as developed and coherent as the totalitarian ideologies of the 20th century. Illiberal democracy purports, as communism did, to offer a more plausible explanation of humanity’s history and future than liberal democracy; it claims to be a form of governance more compatible with human nature, and a superior solution to eternal human problems. Like communism, it is an ideology that may be harnessed to serve the geopolitical interests of the powerful states that embrace it. Americans all too often dismiss Russia as a country that no longer poses the threat it did in the Soviet era because its rulers no longer embrace an ideology that pretends to universalism. This is wrong. They do and it does.

Likewise, many economists and political scientists fail to take this ideology seriously, viewing the rise of illiberal movements in the West as an intellectually empty reflex reaction to stagnant wages, unemployment, or other material grievances. This is a mistake. Strictly economic explanations for the rise of illiberalism are only mildly illuminating—and overall, they are unsatisfactory. Varieties of Caesarism have taken hold, for example, in countries that have experienced respectable economic growth, such as Poland and Turkey. Caesarism, in the United States and elsewhere, is not an affliction of the poor.

To be sure, some of the people who embrace illiberal political movements are bewildered Lumpen who just haven’t thought much about any of this and could be coaxed off the ledge by a “good-paying” job. But the leaders of such movements, and many of their followers, are genuinely and philosophically opposed to liberal democracy. They believe that it does not work or it is doomed to cease working. They do not believe liberalism to be a good in itself. They believe, in fact, that it is inherently wrong—as Putin intimated, undemocratic.

Here is Orbán, in 2014, making this case as clearly as possible, in a paradigmatic manifesto of the New Caesarism:

…the defining aspect of today’s world can be articulated as a race to figure out a way of organizing communities, a state that is most capable of making a nation competitive. This is why, Honourable Ladies and Gentlemen, a trending topic in thinking is understanding systems that are not Western, not liberal, not liberal democracies, maybe not even democracies, and yet making nations successful.

Today, the stars of international analyses are Singapore, China, India, Turkey, Russia. And I believe that our political community rightly anticipated this challenge. And if we think back on what we did in the last four years, and what we are going to do in the following four years, then it really can be interpreted from this angle. We are searching for … the form of organizing a community, that is capable of making us competitive in this great world-race. . .

In order to be able to do this in 2010, and especially these days, we needed to courageously state a sentence, a sentence that, similar to the ones enumerated here, was considered to be a sacrilege in the liberal world order. We needed to state that a democracy is not necessarily liberal. Just because something is not liberal, it still can be a democracy. Moreover, it could be and needed to be expressed, that probably societies founded upon the principle of the liberal way to organize a state will not be able to sustain their world-competitivenessin the following years, and more likely they will suffer a setback, unless they will be able to substantially reform themselves … we have to abandon liberal methods and principles of organizing a society, as well as the liberal way to look at the world.

… The Hungarian nation is not a simple sum of individuals, but a community that needs to be organized, strengthened and developed, and in this sense, the new state that we are building is an illiberal state, a non-liberal state. It does not deny foundational values of liberalism, as freedom, etc. But it does not make this ideology a central element of state organization, but applies a specific, national, particular approach in its stead.

Some of the New Caesars argue that liberalism is something like a superstructure ideology, as Marxists might put it, deployed by the elite class to cloak its ruthless pursuit of its own interests and ambitions. Others will claim it is soft-hearted, fashionable claptrap that weakens the body politic, making it vulnerable to predation. Often they associate, and conflate, liberalism with modernity; many feel a disdain for modernity that shades into nausea. This should not be so hard for us to understand: Many aspects of modern life are genuinely nauseating. The French philosopher Alain de Benoist, for example, is much beloved among the so-called alt-right in the United States.4 He deplores the delinquency, violence, and incivility of the contemporary Western world, which he understands to be the product of capitalism and free trade. He finds a receptive audience, because we are all disturbed by the same things—or many of us are, anyway, and if we are not, we should be. He loathes drugs, virtual reality, and media-hyped sports; he fears the destruction of traditional rural life; he finds modern megacities monstrously ugly and antithetical to the innate craving of the human soul for connection to a community and the quiet, meditative life. Who can argue?

If we are to make a successful case against this ideology, we cannot simply deny that liberal democracy’s detractors have identified real problems, profound problems, with our system of governance and the world it has created. Hillary Clinton’s rejoinder—“America is already great”—was typical of her tragic inability to grasp a tide in the affairs of men. A successful case must begin with the recognition that we have cause to be deeply disturbed and often disgusted with modern life—and yes, modern life is the product of liberal democracy. The argument against the New Caesars will not be successful if we merely deny that liberal democracy results often in things that are rotten and revolting. It must rest upon noting what truly distinguishes their program from that of a liberal: the coercive steps they are prepared to take to rectify these problems.

If this is the kind of society men and women voluntarily create when they are free, its detractors argue—and we must be honest, it is—then freedom must go. That this is what their program really entails is often obscured by the passive language they employ. They rail against globalism—by which they roughly mean free trade and the mixing of cultures. They suggest globalism has been imposed upon them. What is obscured by this language is this: Free trade is—by definition—free. It is the way people engage in commerce when they are not coerced. The only way to stop people from trading with one another is by force, and historical experiments with communism suggest that the amount of force required to keep people from trading with one another is immense.

When they deplore immigration, again the passive language obscures the reality of the program they have in mind. Those who would do away with the free movement of people in Europe, for example, would not only prevent the arrival to their country of people from other cultures, they would prevent their own citizens from leaving. Brexit will not ultimately diminish immigration to Britain by much, given that Britain’s economy would promptly collapse without an inflow of immigrants. But it has served, overnight, to make its citizens’ world ten times smaller. Before the referendum, any British citizen could live, work, trade, and travel unimpeded throughout the entire European continent. Now young Britons face a lifetime of confinement to a small and dreary island.

The New Caesars’ have real ideas, and ideas have real power. We cannot assume they are so self-evidently wrong that there is no need to make a case against them. We cannot delude ourselves that technocratic fixes to the economy will suffice to stop them. We are in a war of ideas.

But never have we been less prepared to fight such a war. We are unprepared because, alas, the critics of liberal democracy are in some sense right. The societies men and women voluntarily create when they are free are prone to a particular kind of decadence. Philistinism and anti-intellectualism take root easily in free societies. Both have accelerated in the postwar period. Such is always the risk in a free society, but it is not—as the New Caesars would argue—the inevitable terminus of freedom. This has happened because of specific, contingent decisions we have made during this time.

Nonetheless, it has happened.

Read more about the New Caesarism in Part II and Part III.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Of the Social Contract, Book IV, Chapter 1, Paragraphs 1 and 2.

There is considerable debate about what Rousseau really meant and whether it is truly antithetical to the idea of rule of law. I use this interpretation of his ideas to evoke an archetype; it is not the only way to interpret his thought.

I described this process in Turkey, here.

Note that this philosopher of the far-right is implacably hostile to capitalism. We only confuse ourselves when we attempt to locate these movements on the traditional left-right axis.

As I read this highly informative, erudite piece my mind leaned upon Shakespeare: "Et tu Brute?!" Where is Brutus when we really need him?

Claire, can you explain this further, please? "The reality, given the underlying demographic problem, is that these newcomers are not a drain to the welfare system but a requirement to sustain it, and no far-right party in power, so far, has had any success in boosting the birth rate."