The most urgent global existential threat remains that of nuclear war

Remarks on the modernization of the nuclear triad

From Claire—welcome back to Doom Week.

The theoretical physicist Lawrence Krauss served for many years as the chair of the Board of Sponsors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. You may recall that the Bulletin was founded, in 1945, by Albert Einstein and other scientists who developed the first atomic weapons for the Manhattan Project.

The Doomsday Clock is set, annually, in consultation with the Bulletin’s Board of Sponsors. In recent years, the Bulletin has expanded its remit; where once it treated only the threat of atomic annihilation, it now includes in its assessment such considerations as climate change, biotechnology, disinformation, and other disruptive technologies.

In 2018, with the clock set at 2½ minutes to midnight, Krauss wrote:

The Science and Security Board for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists assesses that the world is not only more dangerous than it was a year ago; it is as threatening as it has been since World War II. In fact, the Doomsday Clock is as close to midnight today as it was in 1953, when Cold War fears perhaps reached their highest levels.

The Doomsday Clock is now set—and properly, in my view—at 100 seconds to midnight.

Krauss thinks the remit of the Doomsday Clock is now overbroad and the clock best retired. I don’t agree. Doom is doom. If it’s coming at us from all angles (and it is), we’d best face this squarely. If the Bulletin can focus people’s minds—as indeed it did, recently, by pointing out that the hypothesis of a lab origin for Covid19 is in no way a conspiracy theory—I say, “More power to them.”

I asked Lawrence Krauss if he’d be kind enough to contribute to this series. This was his reply.

By Lawrence Krauss

The single greatest threat to humanity

Concerns about racism, immigration, and global warming dominate the media. But there is an astonishing public complacency about the risk of nuclear weapons and nuclear war. Perhaps because it has been 77 years since the last use of nuclear weapons against a civilian population, the recognition has faded from consciousness that of all existential risks facing humanity, nuclear war is the most immediate and the most probable. Indeed, each time I write about the subject—often to coincide with the update of the Doomsday Clock, which I unveiled every year as the Chair of the Board of Sponsors of The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists—the lack of response is deafening.

Despite our complacency, we live in dangerous times. Russia and the United States possess more than 5,000 nuclear weapons each, with more than 1,000 of these on high alert, launch-on-warning status. As the Cosmopolitan Globalist has discussed, the US and Russia have both come within seconds of launching nuclear weapons due to software or human errors that erroneously indicated an incoming nuclear missile strike.

We still rely upon systems designed during the Cold War, when both nations feared a devastating first-strike surprise attack. These conditions no longer obtain. There is no justification for continuing these policies, particularly because a large portion of our nuclear missiles are carried by submarines. Submarines are impervious to a first strike, so our ability to deliver devastating retaliation would remain intact even after a massive land-based first strike.

These fundamental facts—easy to grasp—elude our policymakers in ways that are impossible to understand. Because it is so unfathomable that they could fail to grasp something so simple, many think there must be more logic to what we’re doing than meets the eye.

There is not.

Common myths

Much of the public is under the impression that a normal chain of command and control governs the United States’ use of nuclear weapons. To the contrary, the President—and only the President—can unilaterally order a nuclear weapons strike without approval by any other legitimate government body.

Nonetheless, in his recent book, The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner, Daniel Ellsberg—best known for leaking the Pentagon Papers—demonstrated convincingly, with an overwhelming array of examples, that local commanders at launch sites are willing to launch nuclear weapons without an order from the President if they believe that nuclear weapons have been launched against the US.

Much of the public is also are under the impression that the United States would not be the first to use nuclear weapons in any conflict. In fact, and contrary to promises made by a number of presidential candidates over the years, “No First Use” is not, and has never been, the policy of the United States.

Much of the public likewise believes that nuclear weapons are not meant to be used. In possessing them, many believe, we have only one goal: to prevent others from using them against us. But in fact, all of the nuclear weapons powers have demonstrated a disturbing propensity to behave as if the use of nuclear weapons is a viable military option.

Both the United States and Russia are now spending vast sums to update and modernize their nuclear weapons fleets. They are investing in hypersonic missiles, which are inherently destabilizing because they decrease the time window during which opponents must decide if they face a nuclear attack and launch a counterattack. Both continue to develop missile defense systems. These may create the illusion of safety, but they have never been demonstrated to work against a realistic threat.

In a statement that accompanied a recent setting of the Doomsday Clock, I wrote:

Governments in the United States, Russia, and other countries appear to consider nuclear weapons more-and-more usable, increasing the risks of their actual use. There continues to be an extraordinary disregard for the potential of an accidental nuclear war, even as well-documented examples of frighteningly close calls have emerged.

Let’s explore in detail some of the deeply disturbed strategic thinking now emanating from Washington even as the public focuses on such urgent questions as whether Simone Biles, having succumbed to a case of the twisties, is a sign of everything wrong with America.

Last April, the commanders of the United States Strategic and Space Commands testified before the Subcommittee on Strategic Forces of the House Armed Services Committee about the modernization of the strategic triad. A number of statements were made and accepted by all as obvious truths, even though they are not. The proceedings were not widely reported, although they should have been.

Ranking Member Mike Turner (R-Ohio) opened by saying, “As you know, we have allowed our nuclear deterrent to atrophy.” No one objected to this statement. It passed unremarked.

It is untrue. Our nuclear weapons arsenal is old, but it is ludicrous to argue that our deterrent has atrophied. The one thousand deployed nuclear weapons we now possess are more than enough to destroy much of the world.

“China,” Turner continued, “is more than doubling, according to reports, their nuclear inventory. We know that Russia has undertaken the exotics with Skyfall, the nuclear-powered cruise missile the supposed to orbit the earth with Poseidon that's supposed to pop up from the water, and with other hypersonics and other nuclear weapons.”

It is true that China is building up its arsenal and Russia is modernizing its fleet. This argument—we must catch up—has been used over and over to justify new US weapons expenditures.

But this argument makes no sense in the context of nuclear deterrence. No matter what new weapons Russia and China develop, the existing US fleet will be capable of delivering a second strike sufficient to obliterate any nation insane enough to strike us first. That is all any nation needs to satisfy the requirement of Mutually Assured Destruction, the doctrine that has guided superpower strategic nuclear weapons dynamics for the past 75 years. Responding with a buildup of our own would not make us safer; it would make us less safe. It would create a new motivation, on all sides, to launch on warning. In the best case, it will merely bankrupt all parties. What would make us safer is a treaty by which all parties agree to halt these expensive new modernization efforts.

When you hear such pronouncements, listen to them closely. Ask, “Why?” Don’t assume they must know what they’re talking about. They don’t. What they’re saying is as insane as it sounds.

We then hear from Melissa Dalton, acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans and Capabilities. “Recently,” she testified,

the department initiated the development of the next generation interceptor, which will improve the overall reliability and performance of the ground-based midcourse defense system. The department will continue to bring a more integrated approach to air and missile defense that not only assists with the defense of our forces and allies against multiple types of ballistic missiles, but also addresses the evolving spectrum of airborne and missile threats that seek to inhibit U.S. operations. It will be critical to invest in the right missile-defense technologies in a cost effective and responsible manner to retain our regional and strategic edge long into the future.

This is nonsense. Anti-Ballistic Missile Defense (ABM) is not only a charade, it is inherently destabilizing. It makes us less safe. No ballistic missile defense system has ever been shown to be effective against a realistic incoming threat. Even if it were, no system is 100 percent effective. In well-orchestrated tests, against known incoming objects, our existing systems have a high failure rate. They can be overcome in a simple way: by sending more missiles. If an interceptor system is, say, 70 percent effective when used against a single incoming missile, all the aggressor has to do is launch six missiles instead of one to have a 90 percent chance of successfully penetrating the system. Furthermore, tens or hundreds of decoys may be attached to a single ballistic missile. No existing ABM system has been tested against an incoming threat that includes decoys.

Finally, it’s typically much cheaper to build offensive weapons and decoys than defensive interceptors. Missile defense systems are thus recipes for proliferation. They don’t enhance safety, just the illusion of safety. This illusion is itself destabilizing, because politicians who repose their confidence in these fairytales will not understand the imperative of arms control agreements or seek urgently to negotiate them. This too increases the likelihood that nuclear weapons will be used.

Dalton continues:

For the United States, hypersonic strike systems are an emerging conventional capability that is central to the broader goal of modernizing the joint force to ensure it can deter, and if necessary, defeat competitors in a high-end conflict. China and Russia are making concerted efforts to develop capabilities that are increasingly eroding traditional U.S. war fighting and military technological advantages, including hypersonic weapons systems.

Again, this is insane. Hypersonic weapons allow vastly reduced times between launch and impact; if they are nuclear tipped, for short- or intermediate-range weapons, the response time is vastly reduced. Just like a batter responding to a pitcher, you have to decide to commit a response almost at the moment you detect a launch, removing options for command and control. A “high-end conflict” therefore becomes higher risk. The best alternative, again, rather than responding with a parallel buildup, is to engage in arms control agreements to reduce these escalating options. Remember: our second strike deterrent is safe.

Adm. Charles Richard, commander of US Strategic Command, testified next. “For the first time in our nation’s history,” he noted correctly, “we are about to face two nuclear capable strategic peer adversaries at the same time, both of whom must be deterred differently.” He remarked that China is rapidly expanding its nuclear and strategic capabilities. He then says something that should make every American citizen leap up in his seat and say, “That makes no sense. Why doesn’t the US Strategic Command understand this?” China, he says is “well ahead of the pace to double their stockpile by the end of the decade, and the size of a nation’s stockpile is a very crude measure of its strategic capabilities.”

No. The size of a nation’s stockpile is not a measure—crude or otherwise—of its strategic capabilities. The statement can only be true if you believe nuclear weapons have a strategic purpose beyond deterrence. They don’t. A joint nuclear war is not winnable. It must never be fought. If our stockpiles are large enough to ensure mutually assured destruction in the event of such a war, then any additional stockpiling is at best redundant and at worst dangerous, because the more nuclear weapons, the greater the likelihood of an accident.

No, you aren’t missing anything. This is common sense—to everyone but the people running the show.

Richard continues. “Russia,” he remarks, “remains the pacing strategic nuclear threat.”

It is easier to describe what they’re not modernizing, pretty much nothing, than what they are, which is pretty much everything, including several never before seen capabilities and several thousand non-New START Treaty accountable systems. Nuclear-armed ICBM hypersonic glide vehicle, nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed underwater vehicle and skyfall nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed cruise missile are examples of asymmetric strategies and weapons designed to offset conventional inferiority.

It is indeed deeply disturbing that Russia is modernizing “pretty much everything.” If this were a conventional arms race, it would suggest that we too must modernize “pretty much everything.” But it is not. As long as we have a secure second strike capability, upgrades are not necessary. If you are old enough to remember the “missile gap” President Kennedy falsely promoted to justify a huge US expansion in nuclear weapons, Richard’s argument will ring especially hollow.

“We simply cannot continue,” continues Richard, “to indefinitely life extend Cold War leftover systems, platforms, NC3, and successfully carry out our national strategy.”

Why not? If they do the job?

Turner addresses his next question to Melissa Dalton. The Minuteman III, he says,

has been studied before, and it has been determined that it cannot have life extension, not merely just because of cost, but also because of capabilities. Admiral Richard was describing the capabilities that our adversaries are reaching to. So it was not merely just an accounting aspect. It was also a capabilities aspect. But we have been told that there is a study underway of looking at 200 Minuteman III missiles to maintain the land-based leg of our deterrent while using the remaining missiles to support replacement parts, which of course, again, every time this has been studied it’s been ill advised to look at any extension of Minuteman III, not just merely for cost, but also for capabilities. Ms. Dalton, are you aware of this study? Did you approve it, and what is in this study? Can you comment?

Our nuclear triad involves land-based, air-based, and sea-based weapons. There are good arguments for removing the land-based leg of the triad. As long as our submarine-launched weapons and some fraction of our air-based systems are secure in the event of a first strike, the entire land-based system could be disabled and we would still have a credible deterrent. Moreover, land-based weapons make the areas in which they are located natural targets in the event of nuclear war.

John Garamendi (D-CA) then observed that Admiral Richard’s predecessor had testified before the committee, as recently as 2019, that the life of the Minuteman III—the land leg of the triad—could be extended until 2075. Was this not correct, he asked?

No, replied Admiral Richards. It must be renewed. Why? Because the Minuteman III “is a 1970s era weapon designed to go against Soviet analog defenses,” he replied.

I need a weapon that will work and make it to the target and to expect that in the time frames you’re talking about to penetrate potentially advanced Russian and Chinese systems is going to be a challenge.

Can he explain why the Minuteman might not be able to penetrate these defenses? He cannot. He is assuming that Russia’s missile defense will work. It will not.

Garamendi’s time expires, leaving Congressman Joe Wilson (R-SC) to pick up where Garamendi left. Congressman Wilson is worried about our plutonium pits. The United States, he says, “is the only nuclear weapons state that cannot develop currently a plutonium pit for deployment.” He notes that the committee would like to fund the modernization of these pits, while alluding to Congress’s perennial inability to pass a budget. “How does this uncertain funding threaten the capability of our nuclear deterrent against Russia and China who are building or updating their own triads?” he asks rhetorically, confident the admirals will tell him that unless Congress promptly forks over the money, we’re all going to die. Admiral Richards duly obliges.

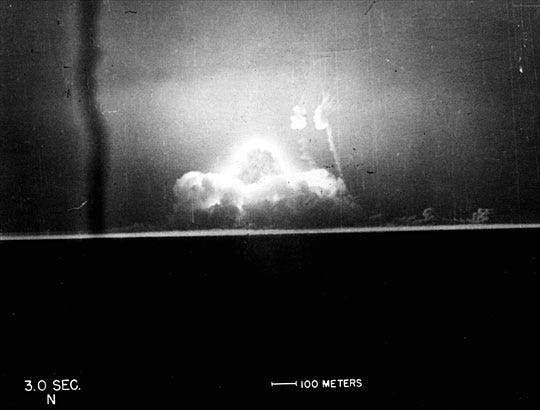

Here the Congressman and the Admiral are either scientifically illiterate or trusting to the public’s scientific illiteracy. Plutonium pits are the hollow spherical shells of plutonium, about the size of bowling balls, at the core of modern thermonuclear weapons. Surrounded by chemical explosives, they implode to high density, triggering fission reactions that ultimately trigger much more powerful fusion reactions in surrounding deuterium and tritium.

Since the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty of 1996 (which the US never ratified), the pits in our nuclear weapons have not been tested. Most of our plutonium pits are 30 or 40 years old. There is constant discussion of building new facilities to produce plutonium pits for fear that aging pits will be too brittle successfully to ignite a weapon.

But the US National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has run ever-more complex computer simulations to determine pit viability. Recent analyses, including a 2007 analysis by JASON, an independent group of scientists who pursue studies for the military, concluded the pits would remain viable for at least 100 years. More recent studies suggest 150 years. As JASON stated:

We judge that the Los Alamos/Livermore assessment provides a scientifically valid framework for evaluating pit lifetimes. The assessment demonstrates that there is no degradation in performance of primaries of stockpile systems due to plutonium aging that would be cause for near-term concern regarding their safety and reliability. Most primary types have credible minimum lifetimes in excess of 100 years as regards aging of plutonium; those with assessed minimum lifetimes of 100 years or less have clear mitigation paths that are proposed and/or being implemented.

In short, there is no credible evidence that our nuclear deterrent capability has been diminished.

Now let us return to the global threat of nuclear war. Even as the US and Russia have been modernizing their fleets, North Korea, China, India, and Pakistan have pursued “improved” and larger nuclear forces. Russia is fielding battalions of intermediate-range ground launched nuclear-armed missiles, capable of reaching Europe. These were banned under the now-defunct Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty from which the US withdrew in 2019. China, which previously relied on a small nuclear arsenal, is expanding its capabilities and deploying multiple, independently retargetable warheads on some of its ICBMs. It will likely add more.

Iran has been enhancing its nuclear capabilities as a result of the ill-fated US decision to withdraw from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action negotiated during the Obama Administration. Whether Iran is willing to return to this agreement at the request of a new US administration remains to be seen. The presence of nuclear weapons in Israel’s arsenal remains a source of tension in the region and an excuse for regional proliferation.

There are strong incentives for Iran and other non-nuclear countries to pursue nuclear weapons. The nuclear nations have been violating the 1970 Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons for the past 50 years. The treaty stipulates that the established nuclear powers must “achieve at the earliest possible date the cessation of the nuclear arms race [and] undertake effective measures in the direction of nuclear disarmament.” Instead, nuclear nations continue to modernize and update their arsenals. For more than a decade, the number of nuclear weapons possessed by the US and Russia have remained roughly constant.

Moreover, actions by superpowers—epitomized by the starkly different response of the United State and its allies to outrages in Iraq versus their response to even more ghastly outrages in North Korea—send a clear message. Nuclear-armed nations are at less risk of being invaded.

To make matters worse, as the Cosmopolitan Globalist has discussed, full-scale nuclear war is not the only global threat to humanity. Even local conflicts can have global consequences. A nuclear conflagration between India and Pakistan involving the exchange of perhaps 100 weapons could lead to a global famine affecting billions.

Over the past few years, arms control efforts—including talks on the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty and negotiations to end the production of fissile materials—have stalled or unraveled. Cooperation on fissile material control and nuclear proliferation among the United States, Russia, and China has lapsed. There are few serious efforts aimed at limiting risky developments in cyberweapons, space weapons, missile defenses, or hypersonic missiles.

We need global recognition that there is no scenario under which the use of nuclear weapons makes strategic sense. In a world where thousands of nuclear weapons are maintained and deployed by countries with rising mutual antagonism, we are all imperiled.

As Einstein said after the first use of nuclear weapons at the close of World War II, “Everything has changed, save the way we think.” Unfortunately, 75 years later, that is still true.

Lawrence M. Krauss, a physicist, is President of the Origins Project Foundation, and was, for a decade, Chair of the Board of Sponsors of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. His most recent book is The Physics of Climate Change.

As Lawrence Krauss says,

“Hypersonic weapons allow vastly reduced times between launch and impact; if they are nuclear tipped, for short- or intermediate-range weapons, the response time is vastly reduced.”

Before the hypersonic era, if a launch were detected, even with all the acute confusion that would inevitably result, there would be time to move the President, Vice President and key military personnel to a location where they had a reasonable chance of surviving the blast. The speed of hypersonic weapons makes protecting key government officials more difficult and as a result they would be less likely to survive an attack.

If the civilian leadership and key military leaders were killed in the initial attack, doesn’t that render the remaining two tiers of the nuclear triad less threatening? After all, upon the death of the President, Vice President, Speaker of the House and President Pro-tempore of the Senate, who would be left to order a retaliatory strike?

In light of this reality, isn’t it realistic to believe that a modernized land based hypersonic ballistic missile capability does provide a deterrent?

While I agree on the whole that modernizing our nuclear arsenal is relatively worthless, there is ample evidence of the worthlessness of treaties in this article as well, not to mention misleading statements pertaining to Putin’s and Iran’s compliance, or should I say lack thereof, with the IRNF and JCPOA, respectively. Furthermore, R&D into hypersonic capabilities can have conventional as well as nuclear applications, and I don’t see why we shouldn’t be fielding comparable conventional weapons systems as strategic opponents like Russia and China, and semi-West-aligned India.