The Long Road to Myanmar

Maps are the key to understanding Myanmar's geopolitical significance. Let Vivek Kelkar show you the routes.

By Vivek Y. Kelkar and the Cosmopolitan Globalists

Myanmar rarely enters Western strategic thinking, or American thinking, to be precise; Westerners probably haven’t given urgent thought to its strategic assets and geography since 1942, when Japan conquered what was then the British colony of Burma. Even imperial Japan did not, at first, grasp the significance of the country they were invading. They saw the conquest as key to cutting off Allied supply routes to China and saw Burma as a source of raw materials: oil, especially; but also rubber, cobalt, and rice. But neither the Allies nor Japan had been eager to turn Burma into a major theater of war. Both failed to appreciate that Burma, febrile with revolutionary sentiment and ripe for armed rebellion, was the soft underbelly of India—the crown jewel of Britain’s Asiatic empire.

Myanmar is again making history. This time, it is Asia’s soft underbelly. Great powers are converging around it, each with its own agenda. The outcome of their machinations will determine the geopolitical map of the future.

Strategic interests first

From its independence in 1948 until 2010, Myanmar was mostly ruled—to a greater or lesser degree, mostly greater—by a ruthless military junta. In 2010, a process of political transformation began. The military, known officially as the Tatmadaw, permitted the nominally-civilian government to release Myanmar’s most prominent dissidents, including Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi. The United States celebrated this turn of events as a vindication of quiet American diplomacy.

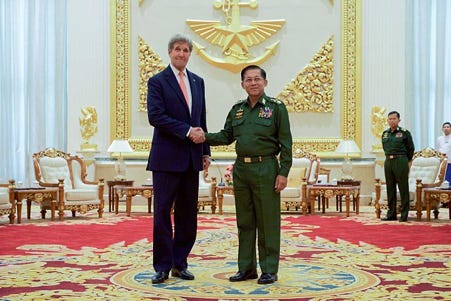

From then until last February, Myanmar enjoyed the longest period of democracy, or quasi-democracy, it had known since the British left. But on February 1, senior supremo General Min Aung Hlaing staged another coup, ousting the duly-elected National League for Democracy along with its head, Suu Kyi. She is again under house arrest, as she has been for the better part of the past three decades.

Protests against the coup, peaceful and violent, swiftly erupted across the country. The junta has been savage in its efforts to repress them. Local monitoring groups say it has killed more than 700, including 44 children, and detained nearly 4,000. Last Friday, according to the UN’s team in Myanmar, security forces used heavy weapons against civilians in the town of Bago, northeast of Yangon (formerly Rangoon), killing 80 protesters.

Western reactions to these events have been as one would expect. The US, the UK, and the EU imposed sanctions on the officers who carried out the coup.1 The UK and the US adopted coordinated sanctions on holding companies controlled by the Tatmadaw. The UN’s human rights investigator for Myanmar urged the Security Council to consider punitive sanctions, arms embargoes, and travel bans.

China, India, and Russia, however, have had no time for these gestures. China and Russia “disassociated” themselves from a UN Human Rights Council resolution calling upon the Tatmadaw to release Myanmar’s elected officials and refrain from using violence on protesters. India expressed “concern” and support for a “democratic transition,” but pointedly refrained from criticizing the junta.

These three counties were among the handful that sent delegates to attend the Tatmadaw’s Military Day celebrations; the others were Myanmar’s neighbors: Bangladesh, Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. Military Day commemorates 27 March 1945, when the Burma National Army staged a national uprising and declared war upon their Japanese occupiers. This year, the Tatmadaw fired indiscriminately on its own citizens, killing 114.

The Scramble for Asia

Inherently, Myanmar is a quagmire. At least 16 rebel militant groups regularly attack the country’s armed forces, some demanding autonomy, many with links to Chinese money and arms. Recently, the army attempted ethnically to cleanse Rohingya Muslims from Myanmar’s Rakhine state, where crucial Indian and Chinese economic investments are located. The genocide scalded the once-luminous reputation of Aung San Suu Kyi. She stayed silent, perhaps because the country’s Buddhist majority loathes Muslims.

Why then did China, India and Russia hobnob with the generals on Military Day? Surely they were not moved by any special enthusiasm for the military regime. But Myanmar’ position in Asia dictated it, geographically and politically. Democracy and human rights take a backseat when you’re scrambling for ascendancy in Asia.

Until now, the West has seemed poorly to understand the strategic value of the real estate Myanmar occupies, at the intersection of South Asia and Southeast Asia, bordering Bangladesh, China, India, Laos, and Thailand. If this weren’t enough, Myanmar’s 2,228-kilometer coastline extends from the Bay of Bengal to the Andaman Sea, near the Malacca Straits—through which nearly 30 percent of global trade transits.

This story cannot be understood without maps. Begin with this one:

The Chicken Neck

Let’s look at another map. Northeast India is connected to the rest of India via a narrow corridor, shown below in red:

The Siliguri corridor—known as the chicken neck—is a cartographic artifact of the partition of Bengal. At its narrowest point, it is less than the length of a marathon. Nepal and Bangladesh crowd its sides; Bhutan caps the northern tip.

Some 50 million Indian citizens—a population the size of South Korea—live northeast of the corridor. Landlocked and wedged between Bangladesh and China, the territory is connected to the rest of India by one railway line. The nearest port, Kolkata, is on the other side of the corridor. A Chinese military advance of 130 kilometers could cut the region off. The prospect agonizes Indian defense planners.

Myanmar is, therefore, India’s gate to its landlocked northeastern states. India has long sought a secondary transit link between West Bengal, shown below, and the northeast:

The obvious path is through Myanmar, by land, then by sea to Kolkata.2 Myanmar is, therefore, much more than a neighbor and trade partner to India (although it is that; India is Myanmar’s fourth-largest trade partner, with volumes rising steadily). It’s a vital route to boost domestic trade between the Indian mainland and the northeastern Indian states. What’s more, rail and road links through Myanmar are critical to India’s plans to establish new trade routes to Southeast Asia and beyond.

Nor are these the only issues. India’s border with Myanmar is nearly 1,500 kilometers long and particularly vexing to Delhi. The refractory northeastern states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Mizoram, Manipur, and Nagaland are are linked—economically, socially, and culturally—to this border region. Around the world, cross-border ethnic ties mean trouble, and this border is no exception. Myanmar’s Chin ethnic group shares kinship ties with Indians in Mizoram and Manipur; Naga tribes live on both sides of the India-Myanmar border; some villages sit astride the demarcation line.

Armed, separatist insurgencies have long plagued these states, particularly Nagaland and Mizoram. The militants, Delhi says, are linked to their ethnic counterparts in Myanmar’s badlands. The Kachin Independence Army is active along the Indo-Myanmar border. The United Wa State Army operates out of Myanmar’s Wa province, which borders China’s Yunnan.

Indian security officials believe China is sending money, training, and arms to the region, the better to keep India’s northeast in perpetual ferment. Our sources say China has designated an ambassador-level official to Myanmar to coordinate the various insurgents and ensure the relationship endures, no matter who takes power in the capital.

India’s problems

Since 2008, India has been strategizing to counter the threat from China in the northeast by pouring money into the Kaladan Multi-Modal Transit Transport Project, slated for completion—after many a delay—in 2023. The route charts a complex course, shown below. It begins in West Bengal, continues through the Bay of Bengal to Myanmar’s Sittwe Port, then joins the Kaladan river, which flows between Myanmar and the Indian state of Mizoram. Modi’s government has hailed the route as the “Future gateway to Southeast Asia.” Its completion is critical to the development of the economically backward northeast; the government views development as the key to its pacification.

In expectation of the opening of this route, India has been building a deep-water port at Sittwe since 2016. The port will be finished this year. India has also made extensive plans for a Mizoram-Myanmar-Thailand 1,400-km road and rail link along the route shown below, although the project has yet to really take off.

Complicating matters even further, the Sittwe-Mizoram link goes through Rakhine state, where the so-called Arakan Army operates. The militia seeks self-determination for the region’s multi-ethnic Arakanese population. The Arakan Army’s guerilla skirmishes with the Tatmadaw frequently disrupt construction. Rakhine State is also home to the Rohingya Muslim community, which has been targeted for destruction by the majority Buddhist population. India can ill-afford a destabilized Myanmar across one of its longest and most vulnerable borders—especially a Myanmar that could become a vassal Chinese state.

China’s problems

China’s 2,129-kilometer land border with Myanmar is no less significant. The Yunnan Province border region is troublesome, particularly, because ethnic armed rebels in the notorious Kachin and Shan states of Myanmar often act quite independently of Myanmar’s centers of administrative power, Nay Pyi Taw and Yangon. In the Shan state, opium derivatives and methamphetamine are produced at near-industrial scale. Jade, luxury hardwoods, even automobiles are all smuggled through the border.

If India’s interests in Myanmar are complex, China’s are, if anything, even more complicated. China’s ties to Myanmar date to the 1950s and ‘60s, when it supported Burmese communist parties against the generals, albeit unsuccessfully. China has always seen Myanmar as its land bridge to the wider Indian Ocean. In the mid 1990s, the EU and the US placed severe sanctions on Myanmar, particularly targeting its agricultural and mineral export sectors. This caused economic disaster. China, predictably, saw the opportunity and stepped into the breach, becoming the junta’s biggest arms supplier.

Official Myanmar government statistics show that Beijing has poured nearly US$9.6 billion into the country’s industry and infrastructure, with a focus, especially, on investments in hydropower, oil, natural gas, and mining. Chinese state-owned companies have built oil and gas pipelines from Myanmar’s offshore fields, in the Bay of Bengal, to Yunnan.

To fully grasp the importance of these pipelines, look at the map below. Almost all of China’s energy arrives via the sea. The whole Chinese economy is powered by oil that comes through the Strait of Malacca, which is why this is the world’s most critical choke point. Moreover, 60 percent of China’s total trade traverses the Strait and the South China Sea.

In 2003, then-President Hu Jintao described this as the “Malacca Dilemma.” By this, he meant that China, lacking an alternative to Malacca shipping, was vulnerable to a naval blockade. “Certain powers,” he said, “have all along encroached on and tried to control navigation through the [Malacca] Strait.” By “certain powers” he meant the United States. In recent decades, China’s strategic discourse has focused ever-more intently on the vulnerability of these sea lines of communication. Chinese planners envision the Myanmar pipelines, and their adjacent rail and road networks, as the alternative—the alternative to the knife the US Navy now holds at their throats. These pipelines are, in other words, China’s very high priority.

The deep-water port and Special Economic Zone at Kyaukphyu, on the Bay of Bengal, is the heart of China’s plan to overcome its encirclement and become a full-fledged superpower. About 512 kilometers from Sittwe, the port is connected to two 870-kilometer pipelines that carry oil and natural gas to Yunnan. Kyaukphyu gives China proximity to India’s ports in West Bengal and access to the Indian Ocean. At first, China sought an 85 percent stake in the US$7.2 billion project. But some in Myanmar’s elected government began grumbling about the country’s rising debt. China reduced the size and cost of the project to US$1.3 billion. Myanmar increased its stake to 30 percent.

In 2009, Beijing began negotiations to build an ambitious US$3.6 billion hydroelectric dam in Myitsone, at the confluence of the Mali, N’mai, and Irrawaddy rivers. The reservoir would have been larger than Singapore, but Myanmar would have received a mere 10 percent of the power it produced. Wary of irreparable environmental, social, and economic damage, locals protested. In 2011, the Thein Sein government announced it would shelve the project in deference to the “people’s will.” No progress on the dam has been made since.

Democracy wasn’t meeting China’s needs

Myanmar’s NLD government came to power in 2016, following the first genuinely democratic elections held since the 1950s. It maintained a regular dialogue with China. Xi Jinping visited Myanmar in 2019 to hawk Belt and Road Initiative projects, declaring Myanmar a “country of shared destiny,” Beijing’s highest diplomatic honor. But the NLD government cautiously declined to put all of Myanmar’s eggs in a Chinese basket.

At about the same time, Myanmar’s auditor-general warned that China already owned some 40 percent of Myanmar’s debt. The interest rates were not attractive compared with those offered by the IMF, the World Bank, and other lending institutions.

Soon afterward, China proposed to build a China-Myanmar Economic Corridor involving many billions of dollars in investment and 38 separate projects. The NLD government approved only nine of them.

In the immediate aftermath of the coup, journalists in Myanmar firmly blamed China. China was displeased with the NLD and Suu Kyi, they surmised, for clipping the BRI’s wings. The speculation is plausible; but if it is true, what followed the coup must have taken Chinese planners by surprise.

In February 2021, protesters placed placards outside the Chinese embassy in Yangon: “China, shame on you. Stop supporting the theft of a nation.” In early March, protesters in Mandalay chanted, “China’s gas pipeline will be burned,” and “Chinese business, Out! Out!” Mandalay is a key staging point for the oil and gas pipeline.

The public became even more enraged with the leak of a document showing that China had requested more security for its pipeline and more intelligence about the armed insurgents along its route. Chinese businesses were torched in Yangon while the army fired on protesters. According to Chinese state media (for what it’s worth), 32 Chinese-owned factories were burnt to the ground, causing US$37 million worth of damage. China demanded protection for its citizens and property, but this only sparked a further wave of anti-China sentiment, both on social media and in the streets.

For China, the stakes in Myanmar are high. It’s no longer just about the pipelines, and the BRI projects, and the arms sales. Now there’s a danger of anti-China sentiment spilling out across Southeast Asia—from Laos to Thailand to Vietnam, and all the way to the Philippines, where even the Beijing-friendly Duterte has expressed outrage about recent Chinese incursions in the Spratly islands.

China grasps that in seeking a stable and subservient government in Myanmar, military dictatorship or otherwise, it’s performing a tightrope act—so much so that Beijing took an exceedingly rare step: On March 11, China signed a UN Security Council statement strongly condemning the violence against the protesters. You don’t see that every day.

China still has a few cards up its sleeve in the form of its well-cultivated links to the many ethnic insurgent groups across the country. There will be no stability in Myanmar unless these groups play ball with the government in Nay Pyi Taw. Their reaction to the coup is still unclear. Some reports indicate they’re unhappy with Chinese “interference.” Others suggest they’re maintaining a studious silence.

The coup on February 1 may have done more damage than meets the eye to China’s ambitions in South and Southeast Asia. If Beijing imagined that subordinating Myanmar would be a bagatelle on its path to regional dominance, it may be in for a massive and unpleasant surprise.

What is Russia’s problem?

Russia shares no border with Myanmar. It’s been maneuvering there nonetheless, poking and prodding just to see what happens. The Russian deputy defense minister, Alexander Fomin, called Myanmar a “reliable ally and a strategic partner” at the Military Day event. Myanmar is certainly a reliable customer for Russian arms; the Tatmadaw purchased at least 16 percent of its hardware from Russia between 2014 and 2019, despite being on most countries’ blacklists. Moscow recently concluded deals to sell the Tatmadaw its Pantsir-S1 surface-to-air missile system, surveillance drones, and radar equipment. It has also been providing them training and university scholarships. China, though, furnishes the bulk of the Tatmadaw’s military equipment, about 49 percent of its spend, and India some 14 percent.

Reportedly, Senior General Min Aung Hlaing considers Russia’s Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu a friend. He visited Russia six times, most recently in mid-2020, and Shoigu visited Myanmar a week before Hlaing staged his coup.

Military sales are not at the forefront of Russia’s calculations, though. Nor are joint military exercises. Russia is playing a long game. At some point, Russia calculates, Myanmar—like Syria—will become central to the many-sided quest for power in Asia. It is the site of the new Great Game. Putin wishes, when it is time, to have the first-mover advantage. He always does.

The Quad’s Options

Sanctions, long one of the United States’ favorite tools, may be entirely counterproductive here. They may make Myanmar more, not less, susceptible to Chinese enticements, despite the grassroots backlash. If the US is seeking the restoration of democracy in Myanmar, its options are very limited.

By now, Washington may have concluded that democracy promotion efforts in countries where strongmen won’t cooperate are doomed to come to naught. Its levers of power over the junta have been diminished. Seeking to halt atrocities against the Rohingya, it has already imposed sanctions on the military. Since the US has neither ties to the junta nor much ability to talk to the country’s insurgent groups, it cannot play mediator. Companies such as Chevron are among the larger operators in Myanmar’s oil and gas industry, but they have little clout compared to Chinese companies.

The Myanmar crisis may become the first, and the most consequential, challenge for the Quad: Australia, India, Japan, and the United States. But they will only succeed if they can coordinate a congruent policy position despite disparate constraints on their policies and different interests in the region.

For India, it’s Realpolitik. New Delhi has refrained from criticizing the Tatmadaw, but it has also developed relationships with the NLD. With both, it emphasizes that it would like to enhance economic ties through investment.

Japan has quietly built its presence in Myanmar over the last decade, too. Although it’s rarely mentioned, most of Myanmar’s population is Buddhist, as is Japan’s, offering a bond of sympathy. Thus far, Tokyo has signaled that it does not favor sanctions; it fears this would only drive the country further into China’s arms. Japan has also built quiet links to Myanmar’s army, especially in the past decade, though economic aid. Last year, Japan was crucial to a truce between the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army. Japan has simultaneously cultivated links with Aung San Suu Kyi and the NLD.

Australia may face a domestic demands for hard action against authoritarian regimes. But if the Quad is to play a role at all in this crisis, India and Japan must take the lead, with American support. The answer may involve offering more economic aid and more industrial investment—on terms favorable to Myanmar—not sanctions.

If the Quad seeks to keep China and Russia from accomplishing their goals in Asia, they will have to play a shrewd, long game. As the Cosmopolitan Globalists have previously observed, the United States is new to the idea of a “shrewd long game.” Let’s see how quickly it learns. Meanwhile, the West would be wise to heed Rudyard Kipling’s sage advice—“This is Burma and it is unlike any land you know about.”

The US House of Representatives passed, by a large margin, a resolution condemning the coup. Most Democrats and Republicans voted for it. But strangely, most of the GOP’s House Freedom Caucus voted against it. We grudgingly admire their intellectual consistency, at least: They’re pro-coup. That’s their principle and they’re sticking to it.

Claire—the obvious path, a naïf might think, is through Bangladesh. But it is not obvious at all. For those who wish to study the India-Bangladesh transit dispute, the scholarly literature is rich.

So much going on here I was unaware of. Thanks.

It occurs to me that Myanmar is less a matter of acquisitive importance to the People's Republic of China than it is of denial importance. With the deal the PRC signed with Russia concerning PRC access to Siberian resources (and the resulting subordination of Russia to the PRC, but that's for another tale) and the nascent PRC colonization of the vasty spaces of eastern Siberia, the PRC soon will have all the access to cheap, nearby and easily protectable supplies of oil, natural gas, timber, gold, etc, etc that are the wealth of that part of Siberia. It has no need of Myanmar's resources or to deal with those troublesome and fractious natives.

The PRC does, though, have a large interest in opening a third front (in addition to the chicken neck and the "disputed" PRC-India border that lies between occupied Tibet and Pakistan) against India. Myanmar also gives a measure of denial leverage to those shipping lanes that feed Japan and the RoK and through which so much of American imports flow.

Russia's interest in Myanmar is much the same as was its interest in northern Korea and Vietnam in years gone by--just to be in the way, to claim relevance, and today to assert a measure of independence from the PRC.

Eric Hines