The Hostage Deal

I don’t know what to think of it. But I’ll be happy if the hostages come home and the killing stops—at least for a little while.

I was about to send this yesterday when I saw that the ceasefire and hostage deal had been put on hold. Netanyahu had accused Hamas of “reneging” on the agreement in an effort to extract further concessions and announced the cabinet would not meet until Israeli conditions were met. Unsure whether everything I wrote had been overtaken by events, I decided to wait, go to bed, and check the news in the morning. I woke up to see the problem—which was never fully explained—has been resolved. Both parties signed the deal this morning, in Doha. The Israeli cabinet is convening to approve the deal as I write.

Several people have asked me what I think of this deal. I told them the truth: I don’t know. I have a strong sense that the accounts we’re reading in the media are seriously incomplete.

From what I can tell, Trump forced Netanyahu to accept the ceasefire terms Biden set out last May—the terms Netanyahu repeatedly rejected as completely unacceptable.

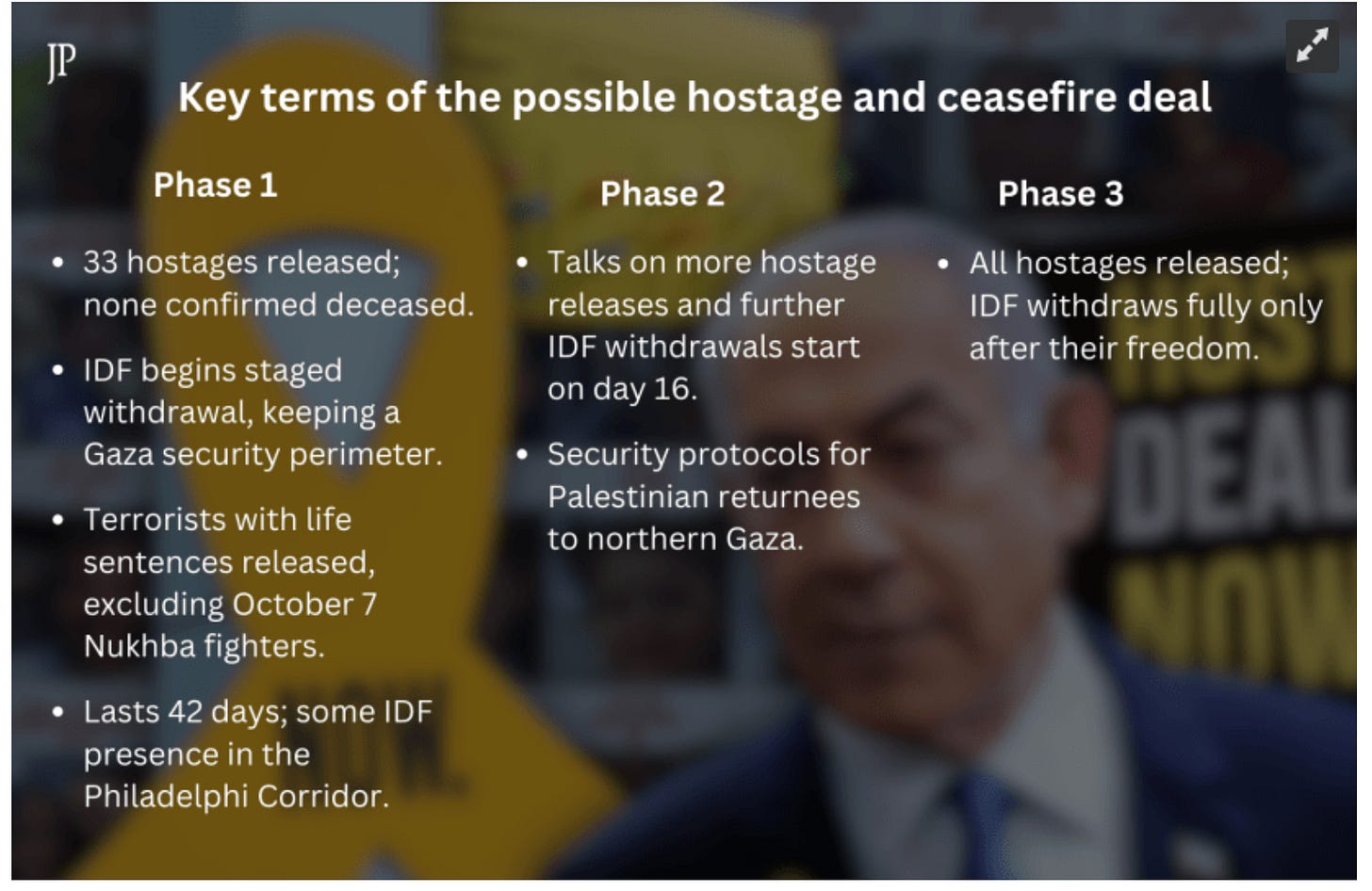

The deal, which goes into effect on Sunday, begins with a 42-day ceasefire. During this time, Israel will withdraw from the Netzarim corridor and all of the populated areas of Gaza to about 700 meters from the border, except in five specified areas, where it will be 400 meters. Simultaneously, the IDF will withdraw from the Netzarim corridor, in stages. Similarly, it will first reduce its presence in the Philadelphi corridor, which separates the Gaza Strip from Egypt, then withdraw from it completely. The Rafah border crossing will be opened within a week from the day the agreement goes into effect. Israel and Egypt will operate it jointly. Civilians, particularly those in need of medical assistance, will be free to cross it as soon as Hamas releases all of the women it has been keeping in captivity. Hamas will be allowed to transfer 50 wounded terrorists to Egyptian hospitals every day, subject to a case-by-case review by both Israel and Egypt.

In the first week, Israel will permit unarmed refugees to return to the north on foot, under Qatari and Egyptian supervision, subject to being searched. After this, they will be allowed to return in their vehicles, which will be inspected by an as-yet unidentified private third-party.

The women and children will be released first, along with the two Americans, Keith Siegel and Sagui Dekel-Chen—33 hostages in total. They will be followed by female soldiers, then men over the age of 50, then young men who are sick or injured. Israel will release about 2,000 convicted terrorists in exchange, of whom some 250 have been sentenced to life imprisonment, which presumably means they have quite a bit of blood on their hands. Israel will also release about a thousand Palestinians, presumably mostly terrorists, captured after October 7. No terrorists involved in October 7 will be released. There will be a massive surge of aid into the strip.

Various news organs (especially those prone to relaying Hamas’s claims without skepticism) have claimed that Israel has a large number of innocent civilians in its custody. It’s possible, even likely, that it has a few. In war, careful jurisprudence suffers. But in June, the Israeli Public Broadcasting Corporation reported that the IDF had been forced, owing to lack of prison space, to cancel planned arrests and release low-risk prisoners to accommodate those considered particularly dangerous. The acute shortage of prison facilities has already led to the release of prisoners who clearly should have remained in custody. It would surprise me if they were holding that many civilians who just had the bad luck of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. (It wouldn’t surprise me if it were true that many harmless civilians have been detained, which I’m sure has been traumatic for them. But I would guess that most of them have already been released.)

The next two phases, which are still being negotiated, will see the release of all the hostages, dead and alive, a full Israeli withdrawal, and a permanent ceasefire.

The US, Egypt, and Qatar negotiated the deal, and both Biden and Trump are proudly taking credit for it.1 It seems that they are both right. The Biden team, of course, was directly involved in the negotiations. Steve Witkoff, Trump’s envoy to the Middle East, was not directly involved in the negotiations, but he held meetings with the Israelis last weekend, and it seems that he delivered a message from Trump that caused Netanyahu to decide he had no choice but to accept the deal. What was that message? I don’t know.

Yesterday, I asked the Cosmopolitan Globalist’s Israel correspondent, Judith Levy, what she thought was going on. “It looks to me,” I wrote, “as if Hamas survives and gets 1000 terrorists back and you lose control of the Philadelphi corridor. Isn’t this precisely what Netanyahu had deemed unacceptable?”

“Yes,” she replied. “It is.”

My suspicion is that Trump’s “there will be hell to pay” was directed not only at Hamas but at Bibi too.

In this region, there are two things that make Trump salivate: adding Saudi Arabia to the Abraham Accords and getting some kind of a framework in place toward a Palestinian state. Bibi of course wants the first but not the second. For Trump to get the second, he has to lean on Bibi about the first.

Bibi’s in quite the bind. His entire catastrophic 18-year project of propping up Hamas in Gaza was expressly designed to maintain Hamas as enough of a viable threat to the PA that a Palestinian state was de facto out of the question—that’s how serious he was about there never being a Palestinian state. If Trump’s price for serving up the Saudis is a Palestinian state, Bibi is stuck. Trump almost certainly had his envoy issue some kind of direct threat. I doubt he said we’ll just take the Saudis off the table (Bibi desperately wants that signature) since Trump wants the deal even more than Bibi does (that Nobel Peace Prize is so close he can taste it), but Trump may have said, for example, we won’t back you when Hamas reneges on the deal (as it obviously will) and you have to go back into Gaza; we won’t protect you from the ICC, we’ll condition the hell out of your American arms, we won’t give you diplomatic cover if (likely when) you have to go back into Lebanon, or—most seriously—we won’t support you if you strike Iran’s nuclear facilities, meaning not only that the US wouldn’t participate in such a strike but that it would refrain from defending Israel when the world starts shrieking oh look look, now the bloodthirsty Jews want to commit genocide in Iran.

The problem Bibi has with Trump (aside from the fact that Trump’s a fickle megalomaniac who feels no true affinity toward Israel, Jewish grandchildren notwithstanding) is that Trump, for all his I Am a Great Dictator bluster, is fundamentally a dealmaker, and he wants credit for a deal that results in at least a pathway toward a Palestinian state. Trump has already done a number of things over here via ex cathedra pronouncement that had been deemed impossible (moving the embassy and thereby recognizing that Jerusalem is our capital and recognizing our annexation of the Golan Heights, for two). It would give him immense satisfaction if he can hook the Big Kahuna—a Palestinian state—which has flummoxed generations of American presidents and diplomats. I doubt he understands that embarking on that course would be rewarding the Palestinians for the worst violence ever inflicted on this country and would likely hasten the committing of more, but even if he does understand it, I don’t think he cares.

The White House issued this statement two days ago:

Note that Biden pointedly remarks that the deal is exactly the same as the one he proposed on May 31.

Two days ago, I sent you this analysis by Dan Perry, in which he, too, argued that Trump forced Netanyahu to accept Biden’s deal:

… what is astounding—at least to anyone who still places any faith in Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu—is that the deal will almost certainly leave Hamas, which massacred some 1,200 people in Israel on October 7, 2023, in power in Gaza.

If current accounts prove accurate, the deal amounts to an acceptance of Hamas terms that have been on the table essentially since the onset of the conflict. Yet just last month, Netanyahu was telling The Wall Street Journal that he was “not going to agree to end the war before we remove Hamas … We’re not going to leave them in power in Gaza, 30 miles from Tel Aviv. It’s not going to happen.” What this means is that Netanyahu is primed to execute an about-face that makes obvious that he has prolonged this war, unnecessarily, for at least half a year. And he’s doing it, almost certainly, because of the imminent return to office of President-elect Donald Trump.

As Perry notes, Israel appeared to be prepared to accept something like this deal last May. But Netanyahu “got cold feet,” as he puts it, and demanded that Israel retain control over the Philadelphi Corridor.

Perry is dismissive of this demand. I’m not. Clearly, if the IDF relinquishes control over the corridor—the primary route by which arms are smuggled into Gaza—Iran will resupply Hamas. Perhaps the deal includes credible assurances from Egypt to police the corridor and prevent smuggling. But such assurances were in effect before October 7. What’s more, Israel will be releasing 1,000 well-rested terrorists back into the Gaza Strip.

Ha’aretz’s reporting strongly confirms the notion that Trump forced this deal down Netanyahu’s throat:

Last Friday evening, Steven Witkoff, US President-elect Donald Trump's Middle East envoy, called from Qatar to tell Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's aides that he would be coming to Israel the following afternoon. The aides politely explained that was in the middle of the Sabbath but that the prime minister would gladly meet him Saturday night.

Witkoff's blunt reaction took them by surprise. He explained to them in salty English that Shabbat was of no interest to him.2 His message was loud and clear. Thus in an unusual departure from official practice, the prime minister showed up at his office for an official meeting with Witkoff, who then returned to Qatar to seal the deal. …

… Witkoff has forced Israel to accept a plan that Netanyahu had repeatedly rejected over the past half year. Hamas has not budged from its position that the hostages' freedom must be conditioned on the release of Palestinian prisoners (the easy part) and a complete Israeli withdrawal from Gaza (the hard one). Netanyahu rejected this condition and thus was born the partial deal proposed by Egypt. …

It’s hard to know how Netanyahu feels about this aggressive behavior. While it provides an excuse he can give to his base, he may resent being dragged into an unwanted deal that will end the war and possibly lead to political upheaval at home. His propaganda machine is pushing the no-choice narrative that it’s Trump. On Monday, laments began to be heard on Channel 14 that Trump isn't what we thought. “I’m surprised all the senior officials in the US administration are saying the same thing,” Yotam Zimri said on the Patriots program. “If this doesn’t happen by the time Trump comes in, Hamas will understand what hell is. I don't understand the Israeli interest in at least not waiting for Trump.” Yinon Magal answered, “It’s because Trump is pressing to do it! That’s what's happening.”

Zimri: “So all his people have been lying—it’s a big disappointment.”

Magal: “He talks about hell and in the meantime sends his envoy to sign a deal. It’s a deal whose impact will be very difficult. That’s the truth.” He added that the last remaining hope is that Hamas will reject a deal: “A cabinet minister told me we need to pray again that God will harden Pharaoh’s heart.”

Monday morning, another Netanyahu mouthpiece, Jacob Bardugo said, “The pressure Trump is exerting right now is not the kind that Israel expected from him. The pressure is the essence of the matter.”

(It’s a wonderment to me that Israelis, of all people, could have been so naïve.)

Immediately after the deal was agreed, the head of Hamas’s political wing in Qatar gave a press conference. Not only do we celebrate October 7, he said, we’re going to do it again.

Israel is torn in two by the deal. Broadly speaking, writes Michael Oren, the former Israeli ambassador to the United States, the left supports ending the war, the right supports winning it. This is probably more a function of Israel’s polarization than anything else. I am neither of the Israeli left nor the Israeli right—nor am I Israeli—but it seems to me the right has the stronger argument. It’s disagreeable to find myself in accord with Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir, but sometimes, even fanatics are right. Of course, Israeli families are desperate to see the hostages returned. But if Hamas is left to reconstitute itself, resume its brutal rule over Gaza, rearm, and do it again, then why was so much blood spilt? For what, exactly, has Israel earned international opprobrium, why has it incurred and endured such horrors, if it has failed to ensure that Hamas will never again massacre at citizens?

Hamas certainly won’t be able to stage exactly the same kind of attack again: That border will never again be left so undefended. But a group that is determined to kill you can find myriad ingenious ways to do it, and a group that believes it is winning—as Hamas surely does, because it has survived—will be highly motivated to dream them up.

Perhaps the calculation is that this is not so much a deal to end the war a deal to get back the hostages. At least, Netanyahu might be thinking, when the fighting resumes—as inevitably it will, because there is no point in being Hamas unless you attack Israelis—Hamas will no longer hold Israelis captive.

Or perhaps the thinking is that this is simply the best that can be done. Perhaps Netanyahu has come around to the view that many, including the majority of the Israeli security establishment, have been urging upon him for months: It is impossible to destroy all of the tunnels and prevent Hamas from returning without permanently occupying Gaza. Occupying Gaza is out of the question, whatever the fanatics in his cabinet might wish. Palestinians, the Israeli public, and the world are all dead set it against it.

But if this is what Netanyahu now believes, then Perry is right to ask: How long has he believed this? If Netanyahu can live with this deal now, why didn’t he accept it last May, saving countless Israeli and Palestinian lives? Last November, as Perry reminds readers, Netanyahu persuaded four members of the opposition to join his coalition, diluting the power of the fanatics—Bezalel Smotrich, Itamar Ben-Gvir, and their allies—who strenuously opposed any deal of this kind. It may well be, as Perry suggests, that Netanyahu always knew this deal or something like it was inevitable, but refused to take it because Smotrich and Ben-Gvir would have collapsed the government. If we accept this interpretation, we’re forced to conclude that month after month of suffering, misery, and death have had but one cause: Netanyahu’s determination to remain in power. This means that Netanyahu is monstrous. That is, of course, precisely what many believe.

But Perry seems simultaneously to be arguing a contrary point, to wit, that Netanyahu did not believe this was an acceptable deal then, and does not believe it to be acceptable deal now. He just had no choice but to accept it. Like Judith, Perry suspects that when Trump warned there would be hell to pay if the hostages weren’t released before his inauguration, his intended audience was Netanyahu every bit as much as it was Hamas.

“Netanyahu prizes Trump as an ally,” Perry writes,

it’s not surprising that he might take previously unexpected steps to appease him. And he wants the protection Trump seems primed to try to afford him on the international stage—especially as regards coercing allies to let him (and his grasping wife) visit without his being arrested, as the International Criminal Court demands. … For Netanyahu, succumbing to Biden would have invited trouble among his own MAGA-like base. Coercion at the hands of Trump—whom Netanyahu has convinced his supporters is the second coming of Moses—can be marketed to the gullible as statecraft.

Perhaps. Perry is putting the worst possible construction on Netanyahu’s motives, and God knows Netanyahu has done little to earn himself the benefit of the doubt. But as Judith observes, there’s more at stake here than Netanyahu’s ability to travel (or stay home) without being arrested. Trump, unlike Biden, is capable of anything, and he has made it clear that he views our alliances as a burden. Should Netanyahu thwart him, Trump could credibly threaten a range of consequences that would be immensely harmful—existentially harmful—to Israel. He could threaten to end the US-Israel alliance entirely. Or he could, as Judith says, tell Netanyahu that where Iran is concerned, Israel is on its own. It could well be that Trump forced Netanyahu to accept a deal that Netanyahu does not believe is in Israel’s interest. (It could also be true that Netanyahu believes this because the deal is not, in fact, in Israel’s interest. There is no reason to believe that by definition, anything Netanyahu believes must be self-serving and wrong.)

Had Biden made such threats, they wouldn’t have been credible. (He did make threats. They weren’t credible.) It was too clear that for moral and electoral reasons, Biden was incapable of abandoning Israel. Biden is a lousy strategist who doesn’t know how to wield power, but this shouldn’t be confused, however, often people confuse it, with callous indifference to Israel’s fate. Trump is, genuinely, indifferent to Israel’s fate. This puts him in a position to dictate terms.

Trump is perfectly capable of abandoning long-standing allies to their doom, and everyone knows it—or at least, everyone who isn’t delusional knows it. (Netanyahu may have been delusional: It seems that many in Israel were.) He would suffer no price in popularity for it. The very people who brayed incessantly that Biden was betraying Israel because because he sought to persuade Israel to accept a ceasefire (including Trump, who accused Biden of being “Palestinian”) would declare it strategic genius if Trump literally switched sides and began shipping the arms we now ship to Israel to Hamas, instead.

Indeed, abandoning Israel would, at this point, probably be quite popular, even without the eagerness of Trump’s base to believe, the moment he tells them so, that we’ve always been or never been at war with Oceania. The left, of course, would be delighted. But the right, once staunchly attached to Israel, is growingly dominated by isolationists and antisemites, of whom Tucker Carlson, Elon Musk, and Candace Owen are only the most obvious examples.

Trump is acutely sensitive to his base’s unspoken desires. He may be calculating that the Groypers are worth more to him these days than the devout Christian Zionists. (He always viewed the Evangelicals as fools; Mike Pence betrayed him; and the business with abortion probably cost him votes.) Certainly, as he has told us repeatedly, he doesn’t think he owes anything to American Jews, who don’t vote for him. He no longer needs Miriam Adelson’s money now that he’s been elected—especially because now he’s got Elon’s, and Elon, needless to say, is not a man with a natural affinity for the Israelites. All of this adds up to an ability credibly to threaten to pull the plug on our support for Israel. So Netanyahu may well have agreed to the deal under extreme duress. But Perry’s other thesis—that Netanyahu is so cynical, and so self interested, that he previously refused to accept a deal he believed to be in Israel’s interests because it would have cost him his coalition—is also perfectly plausible. I don’t know. I can’t know. Probably, anyone who claims to know is lying.

While Perry doesn’t say so explicitly, I assume he believes that Trump forced Israel to accept the deal because he wanted the hostages released before his inauguration, never mind the details. If so, we could speculate that this was important to him because it would validate the idea that he, like Reagan, is so tough that terrorists tremble at the mere sound of his name. He wants the same split screen at his inauguration: hostages liberated, overjoyed families, his hand on the Bible. It would also reinforce a conceit central to his presidential campaign, to wit, that Trump is capable—by means of his superior prowess in dealmaking or his ineffable displays of strength—of imposing order upon a world on fire. (He has probably realized the conflict in Ukraine won’t be resolved within 24 hours of his inauguration, too, which would make it all the more important that he be able to take credit for getting the hostages released.)

Or perhaps there are provisions or guarantees in this deal that have not been made public, but which, if we knew them, would make sense of it. This too is perfectly plausible.

One thing is clear, though: The Israeli right believes that Trump forced this deal down Netanyahu’s throat, and they’re furious about it. (They’re not the first, and they won’t be the last, to lament that they never imagined that leopard would eat their faces.)

Perry imagines that Netanyahu would respond to the charge that he could have accepted the deal months ago this way:

Israel’s military achievements of the autumn—in particular its evisceration of Hezbollah in Lebanon, and the subsequent (and almost certainly related) collapse of the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria—were game-changers. It didn’t hurt that Israel killed Hamas leader Yihya Sinwar, the mastermind of October 7, in September. And there are expectations Trump might “reward” Israel for the deal by seeking to mollify its far right, perhaps by tolerating increased settlement activity in the West Bank.

Perry doesn’t find this a satisfying rejoinder, nor should he. He notes that not only has the delay taken an appalling toll in human life, it has cost Israel a matchless opportunity:

… the Biden administration has, for a year, practically begged Netanyahu to accept a grand vision for the day after the war, which would have included Israeli normalization with Saudi Arabia in exchange for a return of the Palestinian Authority to Gaza—from which Hamas expelled it in 2007—and the acceptance of renewed peace talks on a Palestinian state (a process that has been unfolding on-and-off for over 30 years). As part of that, the Biden administration envisioned the creation of a US-led military alliance including Israel and the moderate Sunni states arrayed against Iran and its proxies—which would have been a strategic coup of the highest order.

Incredibly, Netanyahu seems to prefer accepting Hamas’ terms—likely because Smotrich and Ben-Gvir would not approve of the PA. Consequently, the government’s talking points on TV panels prominently feature the preposterous claim that the PA (which is far from perfect but actively fights and arrests jihadists in the West Bank) is “just as bad” as Hamas, a genocidal jihadist group dedicated to Israel’s destruction and the murder of Jews.

It's a bit silly to argue with an imaginary opponent—I don’t know how Netanyahu would really respond—but I would add that the destruction of Hezbollah and the collapse of the Assad regime are irrelevant. For one thing, it’s not yet clear that the collapse of the Assad regime significantly improves Israel's strategic position. The destruction of Hezbollah unquestionably does, but it in no way diminishes the threat from Hamas. If it was unacceptable to leave Hamas in power or surrender control of the corridor in May, it’s unacceptable now. If it was acceptable, it should have been accepted.

But was it acceptable then? Because this deal means, effectively, that Hamas has won. To win, Hamas had only to survive. And Hamas is rejoicing. Sami Al-Arian, a Palestinian analyst who was indicted in February 2003 on 17 counts for racketeering for Palestine Islamic Jihad,3 says this:

“Netanyahu, by not having his total victory, has been defeated, which by extension means that the resistance, because of its steadfastness, and until the last moment, it’s been in a war of attrition,” said Al-Arian. The Qassam Brigades and the Al Quds Force, the armed wings of Hamas and Islamic Jihad, have “been able to inflict major tactical defeats, in terms of the soldiers, in terms of the plans of trying to have an occupation without cost. [Netanyahu] hasn’t been able to have them defeated or surrender. That’s not happening, which means that Israel cannot claim a total victory, as Netanyahu has been promising.”

Haviv Rettig Gur offers the most optimistic interpretation. Netanyahu, he suggests, has good reason to think the deal is worth the gamble:

… Netanyahu has spent much of the week trying to convince Smotrich that the deal will not mean an end to the war, even if outgoing US President Joe Biden has insisted otherwise. … The argument he’s been making behind closed doors emerged into public view on Thursday in a media statement credited to an unnamed “senior official”—more often than not, journalistic code for a Netanyahu spokesman or even Netanyahu himself.

“Contrary to distorted reports,” the statement read, “Israel won’t be leaving the Philadelphi Corridor” that runs along the Egypt-Gaza border. “Israel will remain on the Corridor throughout phase 1, for all 42 days.” Though IDF forces would redeploy in some parts, “the scale of forces will remain the same, including outposts, patrols, observation sites and control of the entirety of the Corridor.” And then the statement made a dramatic promise: “If Hamas doesn’t agree [in talks over phase 2] to Israel’s demands for an end to the war (the fulfillment of the war’s goals), then Israel will remain in the Philadelphi Corridor on the 42nd day as well, and certainly on the 50th. In other words, in practical terms, Israel remains in Philadelphi until further notice.”

… There’s a reason Netanyahu seems to be struggling to speak clearly — and in fact, has not yet spoken openly to the public about what’s going on in the talks. A large majority of Israelis, including majorities of both Jews and Arabs, support the hostage deal. Some 58 percent support the deal in full, including at the cost of leaving Hamas in power in Gaza, according to an Israel Democracy Institute poll released Tuesday. Another 12 percent support the first phase of the deal—33 hostages released without a full Israeli withdrawal from Gaza—and then want a return to fighting. Some 70 percent, in other words, want the prime minister to sign on the dotted line. But Netanyahu’s problem lies with the 23 percent who do not—who support continuing the military campaign, believe it will lead to a better deal down the road, and are nearly all voters for his coalition.

… Trump’s arrival has fundamentally changed the dynamic. Given the comments of Hegseth and Waltz, Netanyahu can reasonably expect to have American backing for any future escalation. But Trump has repeatedly criticized the Israeli war effort for being slow, indecisive and “losing the PR war.” And so a new dynamic is in play. Israel can do what it takes to win, but Trump, it appears, wants it to show it is willing to try a ceasefire, publicly and clearly. When Hamas inevitably tries to rearm or launch a rocket, Israel will have its excuse to return to fighting, perhaps better prepared and with better intelligence penetration of the Hamas ranks than on October 8, 2023. And in the meantime, it will have handed Trump his political win in the form of a ceasefire, and won his backing for a more intensive fight against Hamas.

This too is plausible. All of these explanations are plausible. I don’t even know which one to favor.

So I don’t know what to think of all of this. I’ll be very relieved if the hostages come home and the killing stops.

As for the rest, we’ll just have to see.

Further reading

Here’s a selection of opinions about the deal.

US President-elect Donald Trump’s pick for national security adviser Mike Waltz says that Hamas must be destroyed and have no role at all in postwar Gaza:

“We’ve been clear that Gaza has to be fully demilitarized, Hamas has to be destroyed to the point that it cannot reconstitute, and that Israel has every right to fully protect itself,” Waltz says. “Hamas cannot have a role. ISIS doesn’t have a role. Al Qaeda doesn’t have a role. These are hostage-taking, murderous, rapist, torturers that never should ever have any role in governing,” he says. Waltz indicates that Israel is currently better placed strategically, with Hezbollah and Iran’s threats diminished, because Jerusalem ignored pressure from Washington for restraint. “I think we’re in a very good place because the Israeli government didn’t listen sometimes to the not-so-good advice coming out of this administration,” Walz says. “And now we are where we are, where Iran is in the worst position it’s been. And that’s not to say this administration didn’t help with shooting down the missiles, [or that] they didn’t help with arms, but they also tapped the brakes as well in a way that I just did not find rational.”

He also says the US under Trump will not hold back on weapons supplies like the Biden administration did when it withheld the supply of 2,000-pound bombs.“You’re not going to see this administration tapping the brakes to make sure Israel can arm itself,” he says.

Victory over Hamas was never going to be decisive. The hostage deal proves what has been known since October 7. Hamas will not simply disappear, and Israel will have to continue its fight against the terrorist group in the future:

Those who oppose the deal are not without reason when they argue that halting the war, even temporarily, could endanger Israel. The logic is straightforward: Hostages will remain in captivity, meaning Hamas retains leverage, and Hamas itself remains. Israel will pause its military operations, pull back from certain areas of Gaza, and Hamas will almost certainly try to rebuild. This dilemma, though, is not new; it was apparent from the very beginning of this war. The moment Hamas abducted so many people, it became clear that achieving a decisive victory would not be possible.

Had someone promised, for example, early on in the conflict that the war would end with Hamas eliminated but without returning the hostages, some might have accepted that outcome, but many Israelis would have viewed it as a defeat. On the other hand, if someone had said that it would be possible to bring all of the hostages home but at the cost of allowing Hamas to retain its capabilities and remain in control of Gaza, that too would have been seen by many as a loss.

This is exactly why a hostage deal is needed. It is a concrete, tangible outcome. A deal that saves lives, bringing both civilians and soldiers back to their families and to their nation. The broader goals of dismantling Hamas’s rule over Gaza and preventing its resurgence are far more elusive. They are objectives that hinge on several unpredictable factors, which could take years to determine if they have been achieved. The hostages, on the other hand, don’t have years—they don’t even have days.

Unfortunately though, in Israel nothing can be discussed without being filtered through the political lens—and the hostage deal is no exception. It has reached the point where it’s possible to predict someone’s stance on the deal based on how they vote. Worse still, there are those who cannot even consider the deal without first assessing how it aligns with their views of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. If they support him, they support the deal; if they oppose him, they criticize the deal.

So, what is the truth? As with most complex issues, the answer lies somewhere in between. Hamas was undoubtedly the intransigent party, repeatedly refusing to engage in meaningful negotiations. However, Netanyahu’s political future was undeniably a factor in his decision-making process. That is the harsh reality. We must also acknowledge that the Middle East landscape was drastically different just a few months ago, and there is room to argue that a deal then would not have been from a position of power for Israel. The recent defeat of Hezbollah in Lebanon, the weakening of Iran, and the continuing degradation of Hamas all made a deal far more viable now than it would have been six months ago.

Caroline Glick is surprised and unhappy:

So is Ruthie Blum. (With respect to Trump, she and Caroline Glick have a strong “If only Comrade Stalin knew” vibe going on):

Postscript: This story is unrelated, but worth your time. “She’s a Syrian refugee, he’s a disabled Israeli Army veteran. They’re in love. There’s just one problem.”

In other Israeli sources, this is less Bowdlerized. He caused considerable offense.

He signed a deal agreeing to plead guilty to one count of conspiracy to contribute services to or for the benefit of the PIJ, served time, and was then deported to Turkey. He is identified in this article only as “a respected Palestinian analyst.”

I‘d recommend the recent episode of What Matters Now podcast of the Times of Israel. Haviv Rettig Gur argues that the hostage deal is NOT the same as last May. And that there are two important differences: 1. Hamas agreed to it. 2. The IDF remains in Philadelphi during the first phase. He also notes that Netanyahu doesn’t like to take risks without a potential for a significant upside. He points out that the shift in Netanyahu‘s stance came after discussions with the incoming Trump administration. Is there a parallel deal between the US and Israel going on? Also Mike Waltz and Pete Hegseth are all very much in favor of strongly discouraging international bad actors from taking US citizens hostage…

Super good essay Claire, thank you.