That leaked intelligence report

Will the nuclear program be up and running again in mere months? Plus a helpful guide to the correct pronunciation of the word "nuclear."

A public service announcement

Let’s get this straight:

I don’t care whether Eisenhower said “nu-cu-lar.” I don’t care how many eminent physicists say “nu-cu-lar.” I don’t care whether “language evolves.” I don’t care if it’s a “regional dialect.” Stop saying that. It makes you sound like an unlettered hick.1

Nucules have nothing to do with splitting atoms. The word nucule refers to one of two things: the female reproductive organ in plants of the family Characeae, or a dry, indehiscent fruit with a bony or leathery pericarp, like an acorn or a hazelnut.

The word nuclear is pronounced new-clear. If you can say “It’s a new, clear day,” you can say “nuclear.” If you say “nu-cu-lar” again, it will only be out of the self-mutilating impulse that causes people to tattoo their entire face.

Thank you for your attention to this matter.

How long will it take Iran to recover?

A strange new coalition unites Tucker Carlson, Marjorie Taylor Greene, Ilhan Omar, Ben Rhodes, and the better part of the editorial board of The New York Times. They all so plainly long to say, “We told you bombing Iran was a bad idea” that one suspects they’d positively welcome being nuked.

The “I told you so” faction has been ululating joyously since CNN reported the existence of a US intelligence document indicating our strikes may have achieved something less than the “obliteration” of Iran’s nuclear program. According to CNN:

The US military strikes on three of Iran’s nuclear facilities last weekend did not destroy the core components of the country’s nuclear program and likely only set it back by months, according to an early US intelligence assessment that was described by seven people briefed on it.

The assessment, which has not been previously reported, was produced by the Defense Intelligence Agency, the Pentagon’s intelligence arm. It is based on a battle damage assessment conducted by US Central Command in the aftermath of the US strikes, one of the sources said. …

While US B-2 bombers dropped over a dozen of the bombs on two of the nuclear facilities, the Fordow Fuel Enrichment plant and the Natanz Enrichment Complex, the bombs did not fully eliminate the sites’ centrifuges and highly enriched uranium, according to the people familiar with the assessment. Instead, the impact to all three sites—Fordow, Natanz and Isfahan—was largely restricted to aboveground structures, which were severely damaged, the sources said. That includes the sites’ power infrastructure and some of the aboveground facilities used to turn uranium into metal for bomb-making.

As usual, the Trump Administration’s response has been embarrassing. “Anyone who says the bombs were not devastating is just trying to undermine the President and the successful mission,” said Pete Hegseth.

Chirpy attack-bunny Karoline Leavitt said the report was “flat-out wrong.”

The leaking of this alleged assessment is a clear attempt to demean President Trump, and discredit the brave fighter pilots who conducted a perfectly executed mission to obliterate Iran’s nuclear program. Everyone knows what happens when you drop fourteen 30,000-pound bombs perfectly on their targets: total obliteration.

I would take this more seriously if any of them cared about protecting classified information. But a different administration would have every right to be outraged. Classified DIA reports don’t belong in the public domain. By obediently conveying this one, CNN made itself party to an internal Pentagon rivalry, not a servant of the public interest. The publication of material like this does not leave readers better informed. It only confuses the careless readers—most of them—and reinforces the moral imbeciles. CNN’s stenographic services will be gratefully accepted by the Iranian regime, which will use it for propaganda. It is especially irresponsible to publish a paraphrased account of the report, as opposed to the report itself, and to do so without explaining to readers what the report really means, which is nothing.

Leavitt’s statement was idiotic. (For one thing, we dropped twelve 30,000-pound bombs, not fourteen.) The shriek about “discrediting the brave fighter pilots” is a non sequitur. A competent press secretary would calmly regret the leak, express dismay at the damage done to our national security when classified information is mishandled, then patiently explain what “low confidence” means in the context of an intelligence report. (Of course, no serious administration would claim that we “totally obliterated” Iran’s nuclear program in the first place.)

Leavitt can’t explain this because she doesn’t understand it. Obviously, she doesn’t understand that no, everyone doesn’t know what happens when you “drop fourteen 30,000-pound bombs perfectly on their targets.” If they did, we wouldn’t have needed Sandia’s terradynamics program, the Air Force Research Laboratory Munitions Directorate at Eglin, or the teams of physicists who’ve been beavering away for years trying to figure it out.

It’s actually not at all obvious what will happen if you drop a 30,000-pound bomb on a target like Fordow. Modern penetration equations, as I noted the other day, were only recently developed. The degree to which a projectile can penetrate a target depends on parameters like the mass, shape, velocity, and impact angle of the projectile; it also depends on the target’s density, which can vary a lot: clay, silt, loose soil, dry soil, wet soil, compacted soil, rock, compacted rocks, sand, dense sand, reinforced concrete, steel—the earth’s mantle is highly heterogenous, and bunkers may be made of many things. The density of a rock depends on its mineral composition, its porosity, and how saturated it is. Rocks may be sedimentary, igneous, metamorphic. Formations may involve layers of materials of different strengths. These layers may slope; they may have fractures or gaps. Fractures and gaps can disperse a bomb blast.

It’s hard to know what’s under the ground. Owing to geological surprises, our pre-test estimates have sometimes been off by as much as 50 percent.

I don’t know what kind of insight we have into the geology of the earth above Fordow. The installation presumably has (or had) many features, like tunnels and caverns, that would make it particularly hard to assess whether 12 MOPs would suffice to “obliterate” it. I assume it is or was covered in multiple layers of steel and reinforced concrete. Reportedly, Iran has developed a new kind of 30,000-psi concrete, which would make figuring this out even harder.

Leavitt is a dope, but that doesn’t mean the CNN report is helpful. Note that no journalist has read the DIA assessment. They’ve only spoken to people who described it to them, and if you’ve ever played Telephone, you know how reliable that’s apt to be. Counter-leakers, I presume, provided the clarification below to Fox’s Jennifer Griffin, who posted it on Twitter:

None of these points were made in CNN’s article, but all of them should have been:

The intelligence community precisely defines “words of estimative probability,” as they’re called. “Low confidence” means “the information is scant, questionable, or very fragmented, so it is difficult to make solid analytic inferences; it could also mean that the IC has significant concerns about or problems with the sources.”

Griffin writes that the “focus” of the report is the Battle Damage Assessment at Fordow. Does this mean the report is only about Fordow? Or is it mostly about Fordow? When she writes that the program could be back on line in “months,” does she mean that activities at Fordow could be up and running again in months? Or that all of Iran’s nuclear activities could be up and running in months?

Griffin doesn’t define “back on line.” Saying the program will be “back on line” within months surely doesn’t mean the program will be right where it was before these strikes. “Back on line” usually means “operational,” but what does it mean in this context?

The report is said to be based on satellite images and signals intelligence. We’ve all seen the satellite imagery. It tells us almost nothing. We can see the puncture holes where the missile entered. We don’t know what happened after that. You can’t see that the entrance to Fordow is “caved in” from the images. Nor can you see that “some infrastructure was destroyed, but the overall infrastructure was not destroyed.” The assessment, therefore, must be based on signals intelligence: information gathered from electronic signals like radio or electromagnetic pulses, or intercepted communications. Since radio pulses don’t tell you much about the condition of infrastructure 300 meters below the surface of the earth, we’re down to “intercepted communications.” What might these be? Iranian officials are all too aware of Israel’s intelligence capabilities and ours (and if they weren’t before, they are now). Is it reasonable to assume they’re forthrightly discussing the state of these facilities on their cellphones? How likely is it that they even know what condition the site is in? If the entrance is caved in, how could they tell whether the infrastructure is intact? Who was speaking to whom? What, exactly, did they say? Without knowing what kind of signals they intercepted, I can’t form a judgment about the value of the assessment.

Likewise, if we believe HEU was moved out of the facility before the strikes, it can only be because:

We saw trucks emerging from Fordow and made an inference;

We intercepted a conversation to this effect; or

We’ve been told this by the Israelis (or another ally) who learned it from a human source. We certainly don’t know firsthand.

Griffin’s sources tell her the DIA report speaks of an “unknown” amount. Is that word—“unknown”—in the report? Or is it the word her sources used? Is it her own? Do we have any clue whether this might mean “almost all of it” or “a tiny bit of it?”

From what we’ve heard about this report, in other words, we can conclude nothing. I trust the DIA. I’m sure they’re good at what they do. But nothing here indicates that they trust this information. It is low confidence.

The leak is surely a symptom of a mighty inter-bureaucratic battle. It’s meant to embarrass Trump, put the shiv in Hegseth’s back, or perhaps to strengthen either the faction that calls for no bombing or the faction that calls for more bombing. But it is not meant to leave us better informed, and news organizations shouldn’t allow themselves to be used this way. When they do, it makes Americans stupider, and in the case of this leak, they served Khamenei’s interests, not ours.

Now, only small children would take Trump at his word when he says the sites were “obliterated.” He doesn’t know. He says anything that pops into his head, especially if he thinks it makes him sound grand, and everyone in his entourage repeats what he said (if they know what’s good for them).

But if you’re tempted to think CNN’s sources must be closer to the truth, don’t be. That’s just a different set of jerks yanking your chain.

Shay Khateri, who’s similarly disgusted by this story, writes:

We won’t know the exact extent of the damage for weeks or months. And I recommend trusting the Israelis on this because all US sources have more reasons to lie than be honest since honest journalism and patriotism are things we don’t do here.

Sadly, that’s right. The US is so fractured that no one can be trusted. We can’t set aside our partisan rancor even to discuss the gravest imaginable questions of national security like adults.

But let’s use some common sense here. We don’t have to outsource our minds to Israel. This is what seems reasonable to conclude from the information so far available to us.

Israel’s intelligence penetration of Iran is so complete that they ran a whole drone factory in Tehran, for years, right under the Ayatollah’s nose. They neutralized Iranian air defenses so completely that Israeli jets flew sortie after sortie over Iran, hundreds at a time, for twelve days running. They spent that time bombing everything and everyone connected to Iran’s nuclear program. They even had time for a few nice flourishes—like blowing up the clock in Palestine Square that counted the days until 2040, the year of Israel’s promised destruction. After that, the US lobbed dozens of cruise missiles at Natanz and Esfahan and dumped twelve bunker busters on Fordow. If you imagine this only set back Iran’s nuclear program by “one or two months,” you’re not thinking about what this would do to set back, say, your office. Imagine trying to roll out a new product line after that kind of ordnance got dumped on your warehouses and delivery vehicles, killing the whole project design team, the VP, CEO, all of the local branch managers, the top guys in Sales, and the head of Human Resources.

Iran cannot possibly replace its nuclear scientists so quickly. This essay by Chuck Pezeshki titled Iran, The Complexity Crisis, and War puts the point well:

… Educated Iranians are not particularly nationalistic at all, and so the various speculations that if the Iranian nuclear sites have been destroyed, the literati will rally to rebuild Iran’s nuclear capacity is highly unlikely. The nuclear program in Iran is a paranoid fantasy of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and the mullahs, who like all disordered religious leaders, dream of the apocalypse. The various scientists participate, I believe, somewhat reluctantly. And as with all hostage situations, implicit or explicit, their mania is tempered. And especially so—regardless of whether sites like Fordow have been completely destroyed, you might imagine being a nuclear scientist and walking into that venue and seeing what had to be massive destruction. It’s not going to fire you up to repeat the B-2 scenario on your head. This time, you just got lucky. And for those true believers, there are Mossad agents circulating, anxious to put a bullet in your brain.

… One of the other prevailing myths circulating in the argument about Iran is the notion “if we bomb it, they already know how to build it, so they’ll just build it back.” That is emphatically not true—and I’ll put my engineering professor-working in nuclear nonproliferation hat to address it.

To imagine Iran will dig Fordow out of the rubble and get things up and spinning again within a month or two, you need to posit something like an infinitely renewable source of talented Iranian scientists. But the set of educated Iranians (or Iranians who could readily be educated to that level) barely even intersects with the set of Iranians who desperately want to build nuclear weapons. Highly educated Iranian elites and mullahs come from different social classes. The former do not, as a rule, share the latter’s Apocalyptic obsessions.

“The images in the [American] press of a monolithic culture immediately recovering and pulling this off are false,” Pezeshki adds, particularly because the United States has already siphoned off the country’s top intellectual talent:

Only the mullahs [are] chanting “Death to America.” All the rest of the Iranian elite want to move to LA. 700,000 already live there. One of the most taboo subjects to discuss in the US is the effect of brain drain on underdeveloped parts of the world …. Do you really think that the 700,000 Iranians living in LA were formally [sic] peasants in Iran? How might that affect the current dynamic?

Israel just killed at least 14 of Iran’s nuclear scientists. Over the years, it has killed more than 25 of them. (The waste and the tragedy of it is breathtaking.) Israel’s ambassador to France told the Associated Press that this will make it “almost” impossible for Iran to build weapons from whatever nuclear infrastructure remains, which is just common sense.

Some, like the former American diplomat Mark Fitzpatrick, demur. “Blueprints will be around and, you know, the next generation of Ph.D. students will be able to figure it out,” he told the AP. Sure. But as the words “next generation” suggest, the timeframe for recovery will not be “one or two months.” Organizations don’t readily recover from the erasure of their institutional memory—especially not when the new hires are too frightened to answer their phones, gather under the same roof, or operate an electronic device.

This leads to the next point. Whatever remains of the regime is now acutely aware of the scale of Israel’s intelligence penetration. Haviv Rettig Gur discusses the implications of this here:

“Hamas,” he says, “managed to pull off October 7 because of Yahya Sinwar—the leader in Gaza—because of his obsessive, pathological fear of Israeli intelligence.”

That drove a compartmentalization that was absolutely hermetic and profoundly paranoid, and also absolutely correct—something none of us understood until we until we saw the Israeli war with Hezbollah, last fall, where we began to understand just how deeply Israel had infiltrated Hezbollah, where we began to see how much Israel could chase leaders, not in the first wave of decapitation assassination strikes, but a month later, when they were in their deepest hidden hideaways. We knew all of it. And we knew where they were in real time, and we could take them out. That Israeli intelligence penetration was fully on display in the last twelve days to an extent Iran had never imagined, could not comprehend. And so now, going forward, we have to assume it’s going to adopt Hamas-scale, Hamas-style compartmentalization.

And here’s the thing. Because of that compartmentalization, Sinwar could never tell Hezbollah about October 7. He took training, he took funding, he took, you know, from the Palestine Corps of the Quds Force of the Revolutionary Guard Corps. They got a lot of support. There was a general understanding they were planning something. But they couldn’t tell Hezbollah it’s happening because they were afraid Hezbollah was penetrated by Israeli intelligence. They couldn’t tell the Iranians. They couldn’t even tell Hamas leaders in Doha. And that massively limited the actual operation they could pull off! Imagine an October 7, but six times bigger, because the Radwan Force in the north launched the same operation it had already trained for across Israel’s northern towns and cities. That was the goal. That was the great strategic plan. That’s what Sinwar hoped would be triggered when he carried out October 7. But compartmentalization prevented that. It shrank down their capacity for producing a massive strategic event.

What Iran will build, going forward, [will be] compartmentalized against Israeli intelligence—now that they understand the capabilities of Israeli intelligence—will necessarily be an order of magnitude smaller for that fear. An Iran that can do smaller things only. An Iran that must watch the skies. An Iran that knows that the Israelis see it as just another Hezbollah. An Iran that once built Hezbollah as its faraway shield, faraway sword, its puppet, its little thing out there that will take the blows of Israel and beat Israel at great sacrifice to itself, and never allow the blows to come to Iran. Iran invented Hezbollah, and now Iran has become Hezbollah. And that’s the great Israeli victory.

Can Iran pull out of this moment? Can Iran, over the next ten years, rebuild institutionally, and then rebuild capacities and rebuild installations and rebuild factories, dig deeper under the mountains and build a new nuclear program, smaller, but the knowledge is already there? Yeah, of course it can. China’s going to help it with the ballistic missiles, we have to assume. But it’ll all be smaller. And it’ll all be more fearful and more compartmentalized. And that’s not a bad thing. That’s the Israeli victory.

The Iranian leadership—and all of its foot soldiers—will be forced to abandon the use of phones and mobile devices. Every conversation, from now on, will require meeting in person. Those meetings will have to be infrequent, or Israel will notice them. Pulling off the complex work of rebuilding factories and transmitting technical expertise, of carrying out a complicated research agenda, will take years. Any surviving scientists will be terrified. It will be awfully hard for them to concentrate.

As Pezeshki writes, making a nuclear weapon requires a high degree of group cohesion and efficient coordination:

… The most important thing to understand is that there is no new tech in creating a nuclear weapon … since 1945, the world has known how to make nuclear fire.

The problem with making one, though, is that it requires a complex manufacturing operation to create enough fissile material to make a bomb. And that requires social cohesion and coordination. … [It] requires a complex supply chain—with lots of people talking to each other, in a coordinated fashion. Hardly a trivial problem in such a factionalized country, as I’ve described above. When you add a dollop of Mossad agents into the mix, your odds of success drop precipitously. It’s not that it can’t be done. Pakistan showed that it could. But it is non-trivial.

… We don’t understand the role of social order in creating manufactured tech. And it shows. There’s a reason, for example, that Taiwan is the center of silicon manufacturing for the world. It’s an outcome of 50 years of social grooming of an entire population to get to the level of discipline and coordination to pull it off. But that kind of thing isn’t easily transferable. Iran has far more tech and ability than its Arab neighbors. I wouldn’t completely discount it. But rebuilding a series of bombed out facilities is not trivial. If you don’t think there’s mass confusion in Iran right now, you’re off your rocker.

The next problem is that unless the DIA report in question is speaking of the Fordow site exclusively, its conclusions are wildly at odds both with what’s been reported in the news and with other professional assessments. The good ISIS, for example, just published a report by David Albright and Spencer Faragasso. They’re among the best in the field. They say:

Israel’s historic Operation Rising Lion and the United States Operation Midnight Hammer have targeted many Iranian nuclear sites, causing massive damage to its nuclear program and setting it back significantly. After 12 days of military operations, a survey of the resulting damage is appropriate. The Institute has obtained high-resolution commercial satellite imagery of the principal nuclear sites, including the Natanz Nuclear Complex, Fordow site, the Esfahan (Isfahan) Nuclear Complex, Lavisan 2 (also known has the Mojdeh Site, the former location of the SPND HQ and other facilities), the new SPND HQ, TABA/TESA Karaj Centrifuge Manufacturing Site, the IR-40 Arak Heavy Water Reactor and Heavy Water (D20) Production Plant, and Sanjarian (a former AMAD site that had recently shown signs of reactivation). The imagery shows various levels of damage and/or destruction at each site. This analysis is enriched by reporting from the International Atomic Energy Agency and the IDF, and by information in the Institute’s archive on Iran.

The attacks can be divided into two basic categories, those against Iran’s ability to make weapon-grade uranium (or plutonium) and those aimed at making the nuclear weapon itself utilizing weapon-grade uranium.

Overall, Israel’s and US attacks have effectively destroyed Iran’s centrifuge enrichment program. It will be a long time before Iran comes anywhere near the capability it had before the attack. [My emphasis.] That being said, there are residuals such as stocks of 60 percent, 20 percent, and 3-5 percent enriched uranium and the centrifuges manufactured but not yet installed at Natanz or Fordow. These non-destroyed parts pose a threat as they can be used in the future to produce weapon-grade uranium.

Complicating any effort to turn weapon-grade uranium into nuclear explosives have been extensive attacks against Iran’s facilities and personnel to make the nuclear weapon itself. Its infrastructure to build the nuclear weapon has been severely damaged. The time Iran would need to build even a non-missile deliverable nuclear weapon has increased significantly.

In particular, major setbacks include: the elimination of, or severe damage to, the majority of the centrifuges at the Natanz site, significant damage to the Fordow underground site, destruction and damage to several facilities at the Esfahan Nuclear Complex, including one used in the conversion of enriched uranium to uranium metal and another that converts natural uranium into uranium hexafluoride. Related, the attack on the IR-40 Arak Heavy Water Reactor has likely destroyed the reactor, eliminating a potential future source of plutonium that could be used in nuclear weapons. In addition, several sites involved in past and more recent nuclear weapon efforts have been destroyed. Not all nuclear sites have been attacked, and further damage assessments are needed for some of the sites, particularly underground sites.

Read the whole report to get a sense of what we can and can’t tell from satellite imagery.

Note this, too:

Before the tunnels [at Fordow] were filled, it is possible that the Iranians tried to move the enriched uranium kept at the site. Dismantling and transporting some of the installed centrifuges, or at least their rotor assemblies, may also have occurred, but this process is complex and time consuming and may have damaged centrifuges. A satellite image showing a convoy of trucks lined up outside one of the tunnel entrances has been interpreted as Iran moving such items out of the site. An intriguing alternative interpretation is that Iran believed Fordow was invulnerable and was bringing sensitive items to place inside Fordow for expected protection.

In other words, it’s hard to figure out how to interpret the things you see from space.

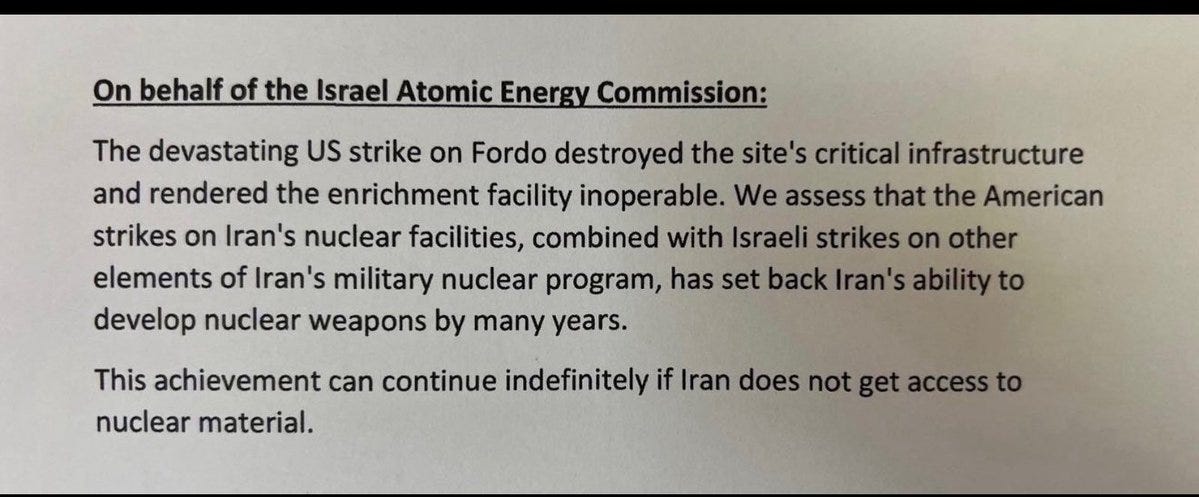

A “senior Israeli official” told the Washington Post that according to their early assessment, the Esfahan site was “annihilated” and the Fordow and Natanz sites were “severely damaged.” The Intelligence Directorate of the Israeli Air Force believes Iran’s nuclear program has been set back “by years.”

According to the assessment of senior Intelligence Directorate officials, the damage to the nuclear program is not surgical but systemic—the cumulative achievement allows us to state that the Iranian nuclear project has suffered severe, wide-ranging, and deep damage, setting it back by years. We will not allow Iran to produce weapons of mass destruction.

The Israeli Atomic Energy Commission also put out this statement:

“Initial battle damage assessments,” said the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “indicate that all three sites sustained extremely severe damage and destruction.” That’s consonant with what’s been reported.

All for what it’s worth. It is hard to accept, but the truth is that we don’t yet know, for sure, how badly the program was set back. It sure seems likely that it was set back a lot, however.

Meanwhile, Jennifer Griffin posted an update to her tweet earlier today:

In other words, the publication of that report served no public interest and illuminated nothing.

I’ll conclude with words you’d never expect from me and which I doubt I’ll ever say again: JD Vance makes a few fair points.

As usual, he’s expressing them like a pompous fool.2 But he’s right to say that this was a selective leak, that it was regurgitated uncritically and without effort to assess its value, and that a journalist who asked why she was on the receiving end of this leak might wind up doing more useful reporting that way than by serving as the leaker’s obedient amanuensis.

Meanwhile, Putin is taking advantage of the world’s distraction. This suggests, unfortunately, that Tim’s pessimism may be warranted, at least in the near term:

Consider it this way. If you say “new-clear,” you will annoy no one. But if you say “nu-cu-lar,” you will reliably distract and annoy a vast number of listeners, no trivial number of whom will imagine curing you through the judicious application of electric shock therapy. (If you doubt me, Google “People who say ‘NOO-kyuh-luhr.’”)

Confronting “NOO-kyuh-luhr” proliferation:

… Of the many language controversies that arouse passions, no other—not '“hopefully,” not the split infinitive, not '“most unique”—seems to bother people as much as this. Even though this pronunciation is now included as a variant in all major American dictionaries, a usage panel convened for the “Harper Dictionary of Contemporary Usage” rejected it by a factor of 99 to 1. Steve Kleinedler, the pronunciation editor of the “American Heritage Dictionary,” said complaints about this variant are the most frequent comment he gets. Merriam-Webster editors have written a special form letter to respond to those who write in to criticize the inclusion of this pronunciation.

Vance was reportedly of the firm opinion that the US had no business getting involved in this conflict and berated the Israelis for “dragging” the US into an unnecessary war.

Regardless of any leaks, it was clear to me almost immediately that we would not have certainty on the effectiveness of these strikes. And also that these strikes would likely preclude future international inspections.

There’s now a half ton of nuclear fuel on the loose in a nation infamous for sponsoring terrorism.

My personal opinion is we were far better off in a multinational agreement to keep Iran from welding nuclear weapons.

The trope leveled at that agreement unfairly was that it would assure Iran’s eventual nuclear capability. But that was false — it only required renegotiation after sunsetting.

This action, on the other hand, assured Iran will be motivated to pursue nuclear capability for its own survival and perhaps as a retributive sneak attack. This insecurity we are now facing was totally avoidable imo.

I invested two plus hours in a straight-through-no-break reading of this, and then laid out nine bucks for the privilege of writing and sharing this post. In the mid 60's I served a 7- year stint in Washington DC as a young man in what would become the Department of Education. It signaled my transformation from an academic into a policy scientist (the formal study of the impact of knowledge on public policy). After that I re-entered the academy, Hands down, Claire Berlinski, your presentation here is one of the most stunning pieces of policy science I have encountered in my now close-to-its-swan-song career. The fascinating Scandia film helped, but you capitalized famously with its use.

I got your point about JD Vance's posting, but you were far. far too generous in the praise you offered.. How could you have resisted underscoring its blatant sycophancy pointing its Trumpian finger at the tired trope about the 'fake media'? I was struck by the wicked contrast between the analysis you provided us all with the "shaped charge" that was Vance's attempt at spin.

Congratulations for your superb work on this, (Time to hit the hay; it's past 10:00 PM.) Thank you for your impressive work on this.