Strategic Blindness

Our institutions are clinging to modern versions of the Maginot Line. Will they wake up in time?

By Simon Pearce

ARE ALL BAD SURPRISES INTELLIGENCE FAILURES?

When states suffer major strategic shocks—think of the United States, for example, when Pearl Harbor was attacked; or the USSR when Germany invaded in 1941; or the US again, on 9/11 and when Kabul fell—official postmortems tend to blame the debacle on an “intelligence failure.”

This explanation is usually incorrect.

In each of the cases above, intelligence agencies produced credible warnings of the impending catastrophe. Political and military leaders received those warnings, but chose not to act. As intelligence officials have been known to lament, it’s awfully convenient for politicians to attribute their policy failures to faulty intelligence—but it’s not so convenient for the intelligence officials.

Hamas’s attack on Israel on October 7, 2023, fits this pattern perfectly. Israel’s political and military leadership were in possession of detailed intelligence indicating that Hamas was preparing a major attack. Leaders even discussed plausible worst-case scenarios. But they chose to do nothing, because they couldn’t bring themselves to believe that Hamas would truly act on its plans.

WHY LEADERS FAIL TO USE INTELLIGENCE

Many political leaders have unrealistic expectations about how much certainty intelligence can provide. Intelligence agencies rarely say, “Event X will definitely happen on Date Y.” Political leaders and their military advisors must synthesize reports about capabilities and probabilities into effective plans of action.

Fear of international condemnation can be an impediment to aggressive preemptive action. Leaders fear they will be blamed for provoking precisely the scenario described in the intelligence warnings.

The worst failures occur when political leaders commit to a course of action before integrating new intelligence. Veteran CIA analyst John Gentry, for example, in an article titled “Intelligence Failure Reframed,” writes that CIA director Richard Helms failed to warn Lyndon Johnson that the war in Vietnam was going badly; he also quashed a CIA report warning against the 1971 invasion of Cambodia. He did so not because the CIA lacked relevant data and insight, but because Nixon had already decided to invade. The CIA did its job. It gathered and interpreted information. But by making it clear that this information would be unwelcome, the leadership failed.

During the Gulf War, Donald Rumsfeld warned of “unknown unknowns.” These days, the most dangerous unknown unknowns are not external. They’re within our own institutions and systems—and we don’t understand them well enough to address them. People within these institutions may understand them, but because this isn’t translated into coordinated action, it’s of little practical use. Modern states have substantial intelligence from satellites, electronic intercepts, and human sources. The missing knowledge is self-knowledge. Even as intelligence agencies get better at collecting and analyzing data, policymakers get worse at understanding what to do with it.

When contemporary politicians think of vulnerabilities, they think first of political vulnerabilities. Their primary focus tends not be material (”What will happen?”) but narrative (“How will it look?”). Politicians are subject to incessant, microscopic scrutiny; this trains them to care, above all, about optics. This has long been true, but the advent of 24-hour news and social media has greatly magnified this tendency.

In 2021, the Biden administration proceeded with an evacuation plan for Kabul that they knew to be extremely risky. Domestic political calculations dominated their concerns: They wanted Americans to see that they were honoring their promise to get out of Afghanistan, and did not want to announce that they were sending more troops. Their inadequate attention to the realities on the ground led to the rapid, chaotic fall of Kabul.

Not all of this can be laid at the feet of politicians. These failures persist, in part, because the public that chooses these leaders rarely understands or prioritizes issues like these—until catastrophe strikes. As Gentry notes:

Congress cannot order presidents to be competent intelligence consumers and has its own collective problems of attention and oversight competence, a failing it finally recognized after September 11 and ameliorated slightly by relaxing term limits for oversight committee members. Expertise in intelligence matters still is not politically rewarding ... There is little political constituency for intelligence agencies, and voters seem not to care.

STRANGE DEFEAT

The fall of France is an enduring cautionary tale about institutional blindness and its dangers, not because history repeats itself precisely, but because it reveals recurring patterns of failure. We ignore these at our peril.

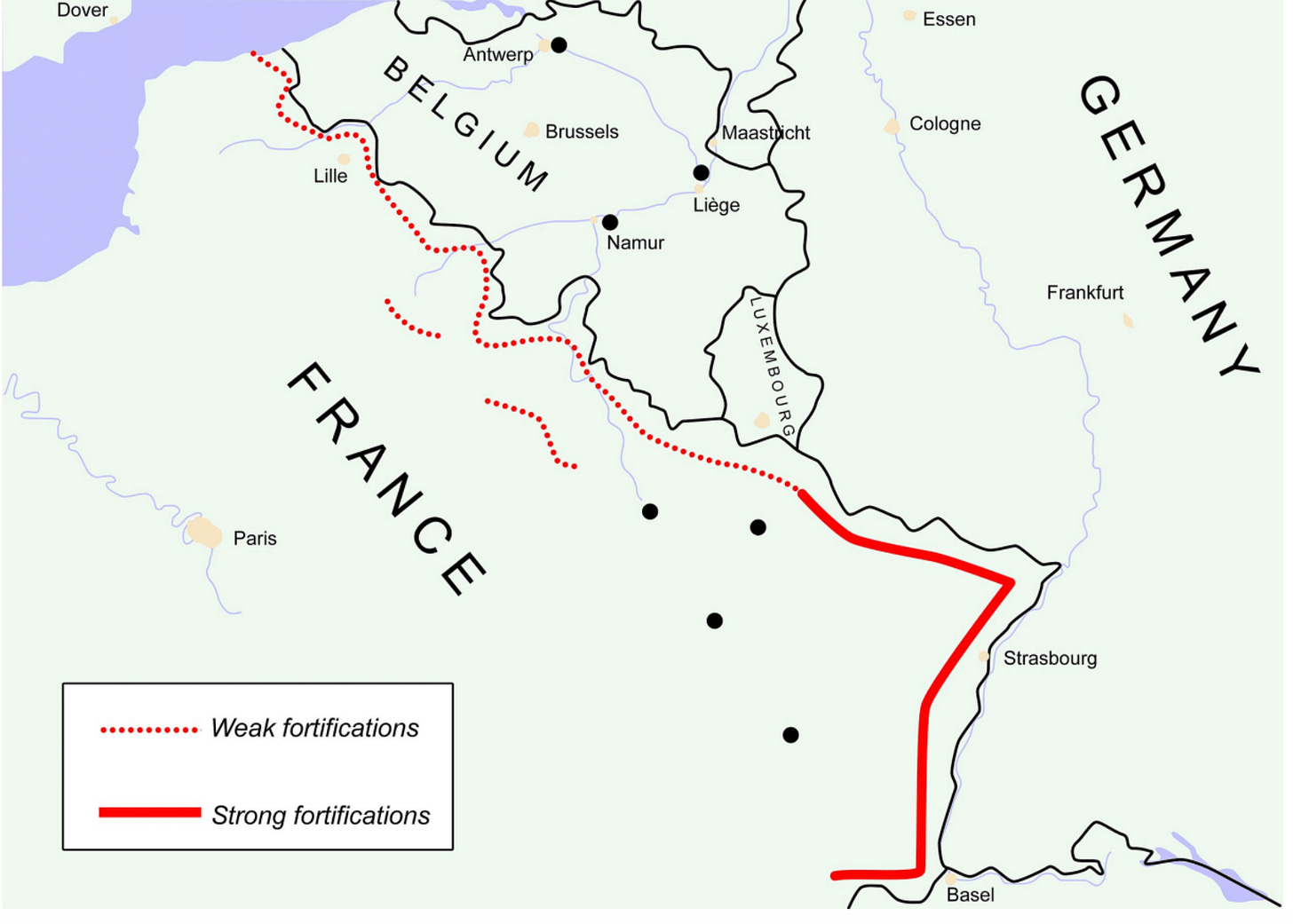

In 1939, when the war broke out, the material balance of forces in Western Europe did not suggest a rapid French defeat. France was able to mobilize a larger army than Germany in the Western theater. It had more tanks, roughly 3,200–3,400 to Germany’s 2,400–2,700. French tanks, such as the Char B1 bis and the Somua S35, were better armored and armed than most of Germany’s Panzer I–III variants, which still formed the bulk of Germany’s armored force in 1940. French defensive fortifications along the infamous Maginot Line were an impressive marvel of engineering. Their design reflected the First World War’s hard-won lessons about trench warfare.

There was a problem, however: The Maginot Line stopped at the Belgian border, so any German attack that went through Belgium could simply go around the line on its northern flank. The Belgians, for their part, insisting upon their neutrality, refused to coordinate military preparations with the French Army.

Germany had not hesitated to invade Belgium in 1914. This fact, and Germany’s aggressive rhetoric since the Nazis had come to power in 1933, made the Belgian attitude dangerously naive. It should have been obvious to them that the Nazis would not care in the slightest about violating Belgium’s neutrality; indeed, if Germany could defeat France by going through Belgium, it would do so without hesitation. This was exactly what they did.

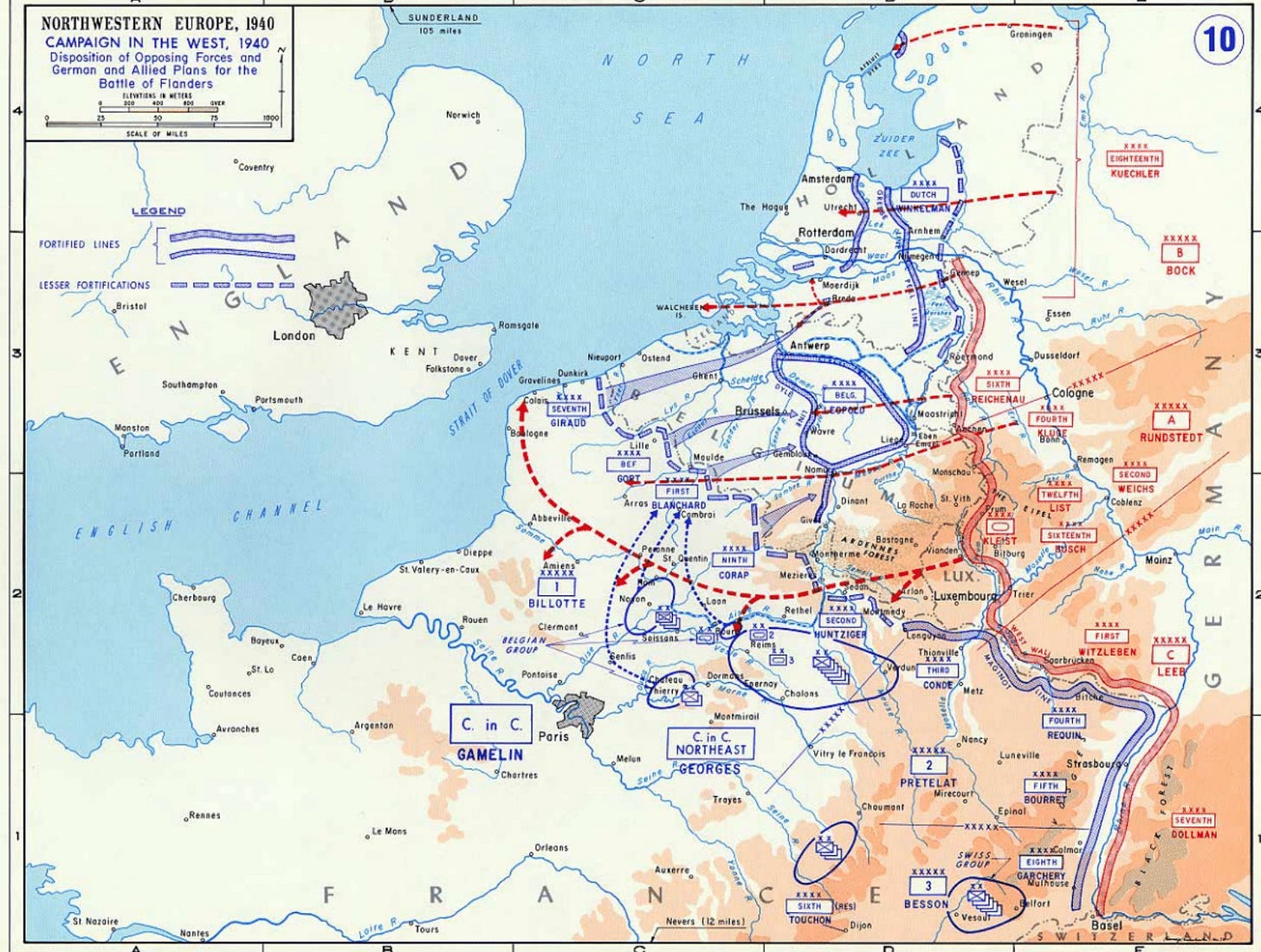

The French response, or rather lack of response, to Belgian naïveté was just as self-defeating. France avoided fortifying the Franco-Belgian border for fear of offending the Belgians—a political decision, not a military one. When fighting began in earnest, in 1940, these problems were compounded. Commanders and their units found themselves impaired by slow, unreliable communications. The British, French, and Belgian armies suffered from a near-total lack of coordination. The Allied plan to oppose the Germans by advancing into Belgium was poorly conceived and even more poorly executed. The creative and well-executed German armored thrust through the Ardennes forest took the Allies by surprise at their weakest point and, very quickly, cut the Allied armies in two, pinning the French First Army and the British Expeditionary Force against the Channel coast at Dunkirk. The trapped armies included many of the Allies’ best-equipped and most experienced units.

It’s tempting to see these events as the consequence of Allied incompetence and German military brilliance and leave it at that. But we need to look deeper truly to understand why this happened. Why were the French, with a large, well-equipped army, unable to resist the German advance? Why did French politicians succumb to despair so quickly? Was there a deeper pattern at work, and if so, what was it?

THE ROOTS OF A CATASTROPHE

France’s defeat was more than a matter of poor leadership and bad luck. It was the result of decades of institutional decay, both in the French Military High Command and across French society.

France’s military and government were deeply traumatized by the First World War. The near-total breakdown of French military discipline, in 1917, weighed heavily on their minds. The 1917 mutinies were not a true revolutionary uprising; rather, the widespread breakdown of obedience stemmed from exhaustion and catastrophic loss.

That was the year in which General Robert Nivelle had promised a decisive breakthrough. But his spring offensive failed, leading to massive casualties. Units across roughly half the French divisions on the Western Front refused to participate in further attacks. Soldiers continued to hold defensive positions, man trenches, and resist German assaults, but they would not follow orders that, in their view, would only lead to futile slaughter.

For French political and military elites, the danger lay not in what happened, but in what almost happened. The mutinies coincided with the Bolshevik Revolution, rising socialist agitation in France, and deep war-weariness. Senior leaders feared it would metastasize into a systemic collapse of authority—the politicization of the army, the spread of revolutionary ideology, fraternization with the enemy, or even a march on Paris. They could clearly see a path from military insubordination to a full collapse of the French state.

Maréchal Philippe Pétain, France’s commander in chief, thus carefully calibrated his response to the mutinies. The army reasserted discipline, but selectively. Of roughly 3,400 courts-martial, only about 50 handed down the death penalty. Broader measures focused on restoring morale rather than instilling terror. The military expanded leave, improved the food and soldiers’ living conditions, curtailed offensives, and shifted decisively toward a defensive posture.

The episode left an enduring imprint. For the interwar generation of officers and politicians, it was a warning that suggested a boundary. It proved that placing excessive demands on a mass army could backfire by undermining discipline and internal consent.

France went on to win the war with significant help from the British Empire and the US. As a result, the institutions and leadership structures that had barely survived the 1917 crisis were preserved, not undone. France’s victory masked unresolved failure.

The German Army drew very different lessons from the war. It had repeatedly achieved striking tactical successes on the battlefield, yet it had failed to translate those successes into a strategic victory. Many historians have noted that German operations throughout the war were often tactically innovative and locally effective. But ultimately, because they failed to produce decisive strategic outcomes, they exhausted Germany’s manpower, economy, and political cohesion without breaking the Allies.

In 1918, the German Army returned home defeated, yet many rank-and-file soldiers were unsure why the war had been lost. Suspicion quickly settled on the home front, where veterans came to believe, wrongly, that internal betrayal had undone them. This grievance deepened and spread, giving rise to a range of violent veterans’ movements, of which the Nazi Party was but one of several.

After 1933, the Nazis—led by World War I veteran Corporal Adolf Hitler—consolidated total control over German society and moved rapidly to prepare for another war. Their core premise was simple, if deeply flawed: Germany would have won the First World War had it not been “stabbed in the back” by a cabal of Jews, Bolsheviks, international bankers, and disloyal Germans. Their mission, therefore, was to correct this imagined injustice in a renewed conflict with Germany’s enemies—Britain, France, Russia, and, eventually, the United States. The uncertainty lay not in whether to fight, but in the details: when, how, and in what order.

In France, the situation was very different. The French Army emerged from World War I nominally victorious, but riven with factionalism and self-doubt. While the Nazis staged a successful takeover of German society and pushed through a radical remilitarization program, France limped along with the political and military structures that had barely survived the war.

Hitler and his government pushed for massive re-armament and focused on offensive warfare. France, too, spent large amounts on its military, but did so in hopes of deterring another war, not fighting one. The French poured concrete, built forts, and produced tanks and guns. But military planners and civilian leaders were hardly enthusiastic about the prospect of using them. The Nazis and the German Army viewed World War I as a humiliation to be solved through more warfare. The French viewed it as a horror to never be repeated.

French military doctrine followed from this sentiment. In his book Strange Victory—the title is an allusion to the historian Mark Bloch’s famous book about the fall of France, Strange Defeat—the historian Ernest May writes that French doctrine had two overarching priorities: avoiding casualties and preventing escalation. In their planning, French generals prioritized keeping any German attack frozen at the frontier. They did not seriously consider developing an offensive combined arms doctrine, and thus had none.

As Marc Bloch himself observed, French doctrine went far beyond fortifications: It was an attempt to impose order on war itself. Command authority was highly centralized; junior officers were discouraged from developing their own initiative and trained to obey procedures, rather than judge situations themselves and act independently. French planning assumed a static battlefield. Intelligence that contradicted this assumption was discounted.

Faced with German speed and improvisation, France’s high command was unable rapidly to adapt. Instead, it hesitated, waiting for events to conform to its expectations—a fatal cognitive freeze. It was not cowardice that caused French generals and politicians to crack and surrender so quickly, but the total failure of their Plan A, and the absence of a Plan B.

The French had spent 20 years building what they believed to be an impenetrable frontier, only to see that frontier smashed, in a few short weeks, by the German Blitzkrieg. They had bet everything on an approach that denuded them of the flexibility required to adapt to surprises. This was true at every level, from the high command to NCOs.

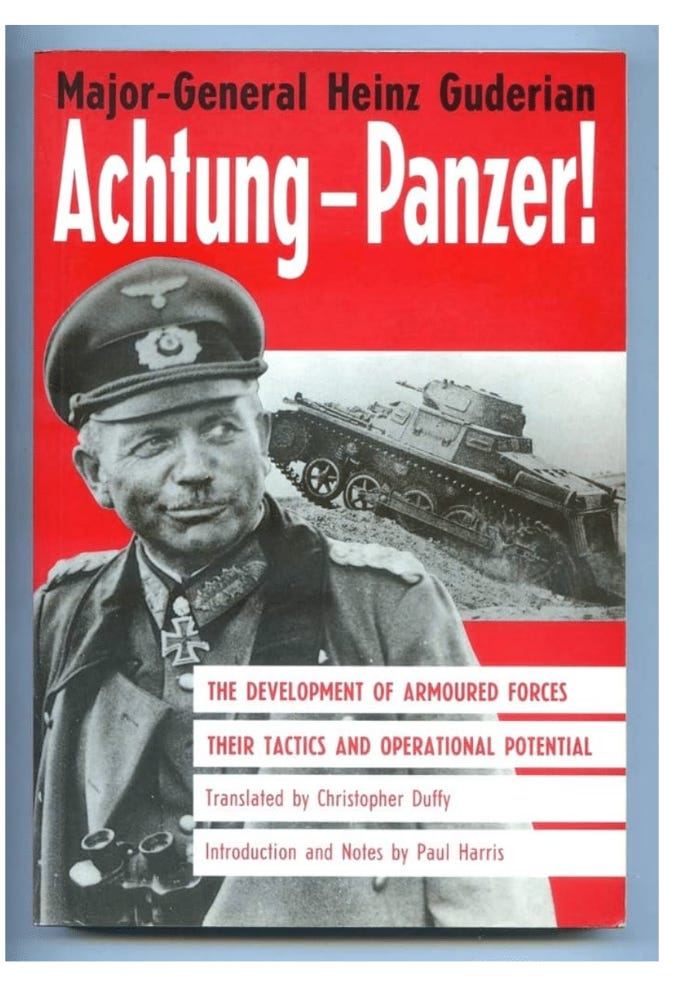

When German tanks poured through French lines in the summer of 1940, the French high command was in a state of shock. It should not have been. Had they been paying attention, they would have known that the commander of XIX Panzer Corps, which led Germany’s sprint through the Ardennes forest to the Channel coast, was Heinz Guderian, the author of a 1937 treatise on mechanized warfare titled Achtung, Panzer! Guderian argued for a new kind of warfare, one involving a heavy concentration of tanks, with infantry and air force in close support. Germany’s Blitzkrieg tactics would not have surprised anyone who had read this book. But even in 1940, very few French generals had heard of it, let alone read it.

Tragically, some French strategists had independently reached the same conclusions as Guderian, notably General Charles de Gaulle, who also wrote a book about mass armored assaults. But the high command, still immersed in the logic of the First World War, was incapable of integrating de Gaulle’s ideas, just as they were incapable of understanding their enemy’s new way of waging war. As in more recent intelligence failures, there was no shortage of information. There was a shortage of leaders who were capable of integrating this information into their worldview and plans.

In the Anglo-Saxon world—especially in the United States—the public has long clung to the reassuring myth that France’s collapse was owed to French moral weakness. The unstated implication is that the British and the Americans would never be so weak. This myth obscures the lesson of that catastrophe. France did not fall owing to a lack of weapons and the will to fight. It fell because it fundamentally misunderstood the war it was fighting. Strategic blindness, not material weakness, proved lethal.

Institutions fail when they cling, defensively, to outdated models of reality. It does no good to gather intelligence if that intelligence is never integrated into policy makers’ decisions.

The Maginot mindset is the mistaken belief that old institutional structures are fit for purpose despite new conditions. The mindset produces institutions that look impressive on paper even as they quietly lose their capacity to function under stress.

OUR PREDICAMENT

The Trump administration is not unaware of American military power. To the contrary, it is unusually confident in it, and increasingly willing to wield it openly. From Venezuela to Greenland, coercive pressure has returned as an instrument of American statecraft. The administration does not see NATO as a stabilizing architecture, but as a burden—a collection of dependent allies to be managed, pressured, or reminded who’s boss. They see the alliance not as a strategic asset but as a tiresome, inherited obligation.

Open contempt for the so-called rules-based order reinforces these views. Figures such as Trump adviser Stephen Miller dismiss this order as a childish fiction layered atop the only thing that truly matters: hard power. In this reading, norms, institutions, and even treaty commitments are decorative. Force is real; everything else is theater.

Even if one accepts that the rules-based order has always rested upon coercion, or that acquiring full control of Greenland has truly become an American strategic imperative, the Trump administration’s worldview is blind, strategically, to the broader system in which it operates. Their error is not misunderstanding power. It is misunderstanding how hard and soft power are entwined and what this entails.

For eighty years, a dominant US military has been embedded in an alliance system that made American power predictable to allies and legible to adversaries. That predictability wasn’t a moral luxury; it was essential to the functioning of the global economic and security system the United States built, placing itself at the center. By treating NATO as a burden, the administration is making its own species of Maginot error: It is confusing visible strength with systemic resilience. Trump officials assume that because US military power is overwhelming, the security architecture it supports can be neglected or coerced without consequence.

This is not likely to be true.

EUROPE’S BLINDNESS

None of this absolves Europe of responsibility. European governments spent decades assuming that US protection was permanent, unconditional, and costless. They behaved as if American security guarantees were not contingent, but part of the natural environment. Instead of building their own militaries and the political cohesion of their societies, most European states prioritized domestic consumption. Defense budgets shrank. Industrial capacity atrophied. Strategic autonomy was a slogan, not a program. Europe behaved as if history had ended, even as it outsourced the enforcement of that illusion to Washington.

This was not free-riding in the crude sense. It was a deeper form of institutional laziness, reflecting the belief that the system would renew itself automatically. European leaders assumed that because NATO had worked, it would continue to work, without asking why it had worked in the first place and whether those conditions still obtained. These assumptions proved deadly to the internal coherence of the alliance.

By failing to behave as serious security actors, European states reinforced the American perception they now resent—that NATO is a burden, not an asset. Dependency bred contempt. Contempt accelerated withdrawal. Both Europe and the US perceived bad faith in their counterparts’ behavior, but in fact, both were responding rationally to incentives, and these incentives were shaped by long-term neglect.

The tragedy of this moment is not just that the alliance is fraying, but that the shared language needed to repair it has also eroded. The United States speaks in terms of power and leverage. Europe responds in terms of norms and obligations. Both are talking past each other, trapped in assumptions that no longer align with reality.

The consequences of this erosion are not confined to military coordination. The security guarantees that make deterrence credible also make global economic coordination possible. When the United States weakens or exploits the alliance system that made its power predictable, it does not merely undermine trust among allies; it destabilizes the financial architecture that rests on that trust.

CONFIDENCE AND RESERVE CURRENCIES

The global demand for US dollars and treasury bonds is not an abstract vote of confidence in American balance sheets. It’s a byproduct of the security order the United States has historically underwritten, one where the US defends its allies, protects trade routes, and serves as the system’s enforcer of last resort. When the US treats that security architecture as transactional or conditional, the economic consequences don’t appear overnight. They accumulate at the margin. Confidence erodes well before dollar-dominance collapses.

Like military deterrence, a reserve currency’s status weakens, first, through doubt, not deliberate defection. A currency can remain dominant for quite some time through inertia. What we see is not a collapse so much as a hollowing.

If hard power ultimately decides outcomes—if territory, resources, sea lanes, and missile geometry are all that really matters—then why should the United States restrain itself at all? Why not coerce now, while it still can? Quite apart from the obvious moral point, the answer is that episodic displays of strength can’t sustain reserve-currency status. That status reflects the cumulative expectations of thousands of actors who decide, every day, where to store value. Military might can seize ground, but it can’t compel central banks, insurers, pension funds, and sovereign wealth managers to underwrite the liabilities of a state whose power has become unpredictable or selectively hostile. Financial systems respond to risk. The US currency won’t be abandoned because the alternatives are superior, but because unpredictability creates risk, and investors find this unattractive. It can be quite some time before the substitution is visible.

INFORMATION ISN’T ORIENTATION

The erosion of NATO and the weakening of the dollar are not isolated failures. They reflect a deeper form of strategic blindness. Two archaic assumptions, in particular, appear to be governing US decision-making.

The first is that the US military’s power is uncontested. It is not. While the United States retains overwhelming capabilities, it no longer enjoys the capacity for decisive escalation dominance against peer competitors, most notably China, across multiple domains, simultaneously. The margin for coercive action without retaliation has narrowed dramatically.

Precisely because that margin has narrowed, alliances are more critical to American security than they have been since 1945. Alliances are force multipliers and mechanisms for sharing risk; they distribute deterrence across multiple actors, and they complicate adversary calculations. But at the moment alliances matter most, the United States is signaling—implicitly and explicitly—that its alliances are contingent and its allies disposable. Strategically, this is like tearing up one’s insurance policy in the middle of an earthquake.

The second assumption is that the rest of the world will continue to finance American power, no matter how that power is used. This, too, is false. The dollar system endured because the world believed American military power was the guarantor of global stability, not a tool for the arbitrary coercion of allies, partners, and neutral states. When military power is wielded transactionally or punitively, confidence in the system that power supports erodes.

Western security institutions, and American institutions especially, have extraordinary visibility into their adversaries’ capabilities. Lack of information is not the problem. The failure lies elsewhere. It occurs because these institutions are far less nimble at integrating this information and formulating new assumptions about power, deterrence, and legitimacy.

Thus action lags reality. Leaders continue to act as if military primacy guarantees their freedom of action, and as if their financial dominance is immune to their exploitation of it. These outdated assumptions persist not for lack of evidence to the contrary, but despite that evidence.

THE UNANNOUNCED WAR

Major war has not disappeared. China is preparing for a military confrontation in the Taiwan Strait. The risk of escalation is very real. The United States and its allies understand this, and they are planning accordingly. But their focus has left them with a strategic blind spot.

While Western militaries plan for a shooting war, China applies continuous pressure, below the threshold of open conflict, to undermine the cohesion of the West’s alliance systems, the legitimacy of its political systems, and the social trust that makes military power usable. Beijing doesn’t need to defeat US forces in battle if over time it succeeds in hollowing out these alliances and rendering America’s military primacy strategically irrelevant.

Western governments largely leave these domains uncontested, not because they lack the appropriate tools, but because the responsibility for using them is spread across institutions that don’t share incentives, timelines, or a single authority. This is not a failure of intelligence. It is a failure of orientation.

Western leaders still expect conflict to announce itself through overt military escalation. They monitor their rivals’ militaries closely and manage this domain competently. But this is not where they are most vulnerable.

China deliberately applies pressure in a way that permits them to deny that they’re doing so deliberately and avoid triggering retaliation and escalation. Gray-zone attacks lie outside the categories Western security institutions were designed to confront, even when their cumulative effects are obvious.

China’s advantage, here, is not omnipotence or internal harmony, but institutional alignment. Its gray-zone tools, political authority, and strategic timelines are integrated. Western institutions were deliberately designed to avoid this kind of centralization of power. This is exactly how France failed in 1940. France did not miscount German forces; it prepared for the wrong kind of war. Its leaders assumed they would see a familiar pattern of escalation, giving them time for deliberation. Germany denied them these advantages.

Western security planners are now making the same species of error. They are fixated on a less-likely conventional conflict, discounting the slow erosion of power that will precede it and perhaps even make it unnecessary. If open conflict comes, over Taiwan or elsewhere, it will arrive years after the West’s institutions have been so thoroughly undermined that the outcome is predetermined.

SILOED INSTITUTIONS IN A NETWORKED WORLD

Western institutions remain organized around slow, siloed models of expertise. In earlier eras, the realms of security, finance, energy, and legitimacy interacted over years or decades. That slower pace made institutional fragmentation survivable. Today, these feedback loops operate at near-real-time speed. Events in one domain trigger immediate consequences across others.

Coordination can no longer be informal or delayed; it must be explicit and continuous. This creates a structural vulnerability. Our adversaries don’t invent the destructive pressures on our societies; they simply exploit the fractures that are already present—polarization, institutional distrust, financial fragility—and amplify their effects.

Meanwhile, we growingly select our leaders for their gifts in signaling, coalition maintenance, and short-term emotional management over their long-range strategic judgment. Senior political leaders struggle to distinguish internal political pressure from external strategic reality. When that distinction collapses, the executive branch quickly loses its capacity to orient itself, and society, under stress.

When existing models of geopolitical reality fail in this fashion, institutions tend to freeze. Leaders and experts build careers on assumptions that no longer hold. When reality violates these assumptions, they reach instinctively for outdated playbooks instead of revising their frameworks. This paralysis is not incidental. Adversaries rely on it.

The Covid pandemic revealed our vulnerability to this kind of failure. We were unable effectively to coordinate our systems for managing health, the economy, security, and industry. Politicians shut down whole lines of inquiry (for example, about the virus’s origins) when the answers might threaten their institutions or their reputations. The result was not coordinated adaptation but cascading second-order damage: strained supply chains, degraded trust, and long-term economic damage.

Our leaders behaved as if an all-domain rupture was a series of isolated technical problems. This is the defining failure pattern of the twenty-first century: We observe everything, but we cannot orient. Decision-makers default to inherited assumptions. Actions fail to align with reality. New data arrives, but no one learns from it.

The core failure is not a loss of control, but a a failure to understand what matters, when, and why. Growingly, Western political systems are unable to swiftly generate and sustain, among their publics, a shared understanding of reality.

Our adversaries are not irrational. They operate, however, within different epistemic frameworks, and they pursue objectives that do not map neatly to Western assumptions about prosperity, stability, or institutional continuity. Our strategic failures arise less from misreading our adversaries’ capabilities than they do from assuming that our own standards of rationality apply to everyone else.

Our deepest vulnerability is domestic. Democracies have become structurally ill-equipped to resolve disagreement, ambiguity, and novelty without fracturing. The erosion of even a minimal consensus among our elites, the collapse of public trust in our institutions, and the disappearance of a shared worldview add up to something much more significant than a cultural inconvenience. These are direct strategic liabilities. When societies lose the capacity to distinguish between uncertainty and falsehood, between pluralism and incoherence, and between dissent and subversion, they become auto-destabilizing.

FROM CONTROL TO NAVIGATION

We must abandon the illusion that institutional continuity equals resilience. Continuity without adaptation does not produce stability; it produces brittleness. Systems optimized for a world that no longer exists will defend their procedures long after they cease to serve any useful goal. What we need is not a return to control, but a shift toward navigation.

Adaptive systems don’t try to reduce complex realities to rigid plans, nor do they reduce them to more legible fragments. They develop the capacity to operate amid uncertainty while maintaining coherence of purpose. This demands leadership that is capable of revising assumptions without denial, and institutions that are willing to treat epistemic correction as a strength, not a concession.

History won’t pause while our institutions argue about first principles. History advances, indifferent to our inherited narratives and the comfort of our organizations. Democratic states should not be asking whether they can preserve the arrangements they inherited from the late-twentieth century. They should be asking whether they’re capable of adapting quickly enough to remain governable in the twenty-first century.

Crucially, this shift can’t be imposed from the top down. Orientation is an emergent property of societies that retain the capacity to interpret reality at multiple levels simultaneously. National leadership still matters, but its role must shift from control to enablement. It must create the conditions for distributed adaptation rather than trying to substitute centralized power for this more profound change. Without this broader renewal, institutional reform risks becoming another Maginot Line—impressive on paper, brittle in practice.

Simon Pearce is the President of Emotif, a strategic business consultancy. He writes regularly about economics, systems and civilization at The Liminal Lens.

Super interesting and compelling framing. Also feels like a big ask. What are the levers through which such a fundamental institutional adjustment might be achieved? Is there any historical precedent for such a change in strategic and operational orientation without disruptive destruction first?

Simon Pearce: "Gray-zone attacks lie outside the categories Western security institutions were designed to confront, even when their cumulative effects are obvious."