On Vexatious Comments

Also: When did we elect Elon Musk?

I’ve been at work editing two outstanding essays, one about our betrayal of Afghanistan, the other a response to an article recently published in Quillette suggesting that the Lab Leak hypothesis is a bust. They’re both long, complex, and challenging to edit, so that’s taken up all my time this week. They’ll be worth it.

Story of the day

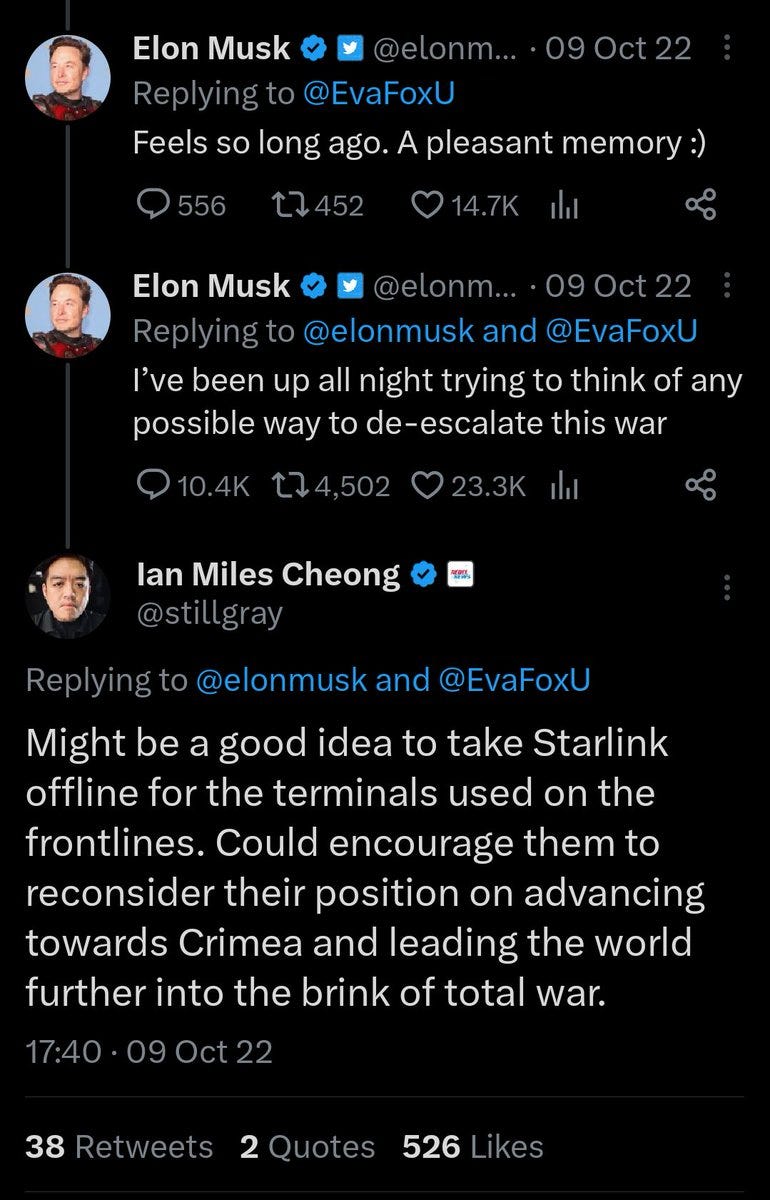

Elon Musk acknowledges withholding satellite service to thwart Ukrainian attack. The Starlink satellite internet service, which is operated by Mr. Musk’s rocket company SpaceX, has been a digital lifeline for soldiers and civilians in Ukraine:

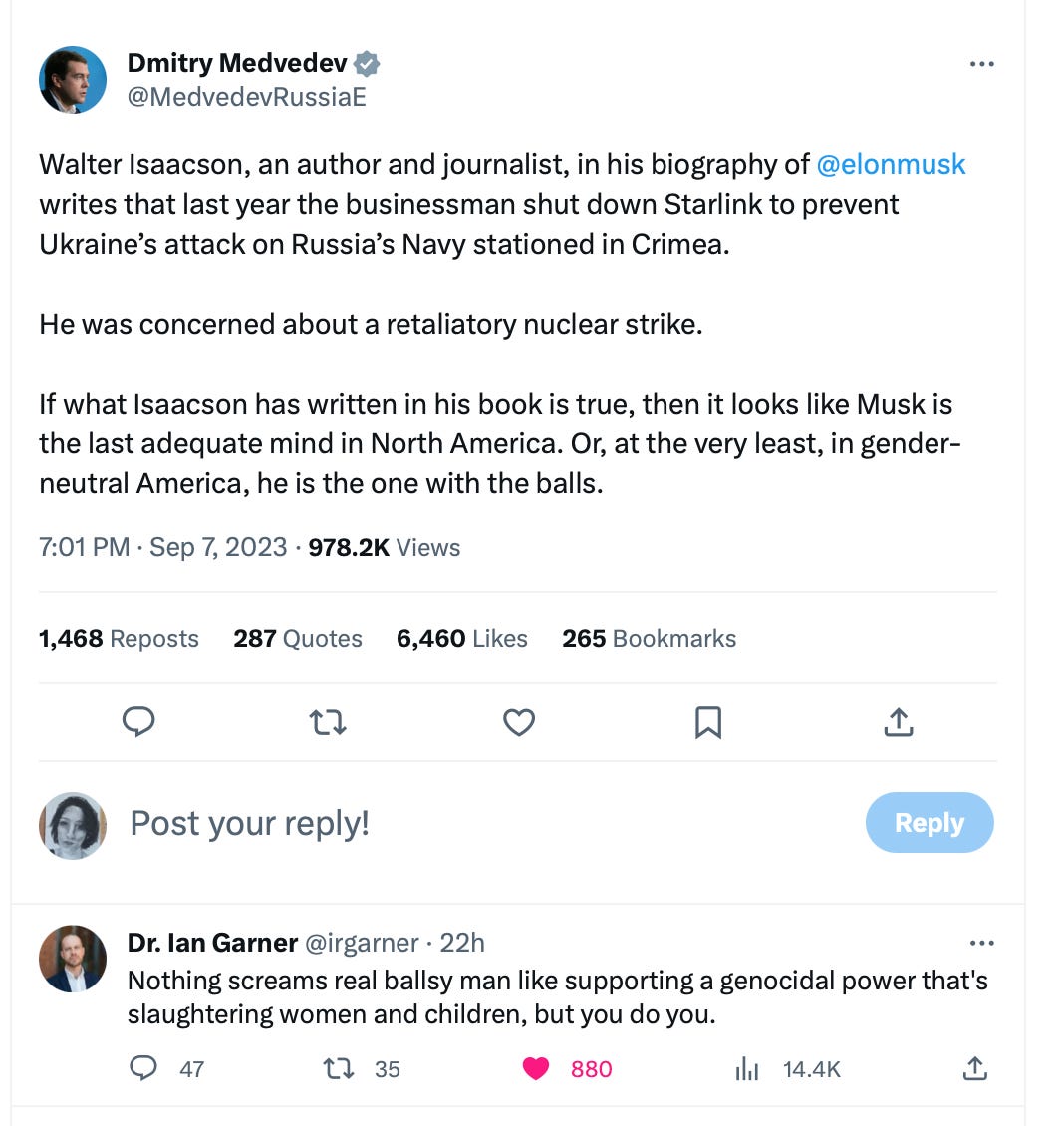

… On Thursday, CNN reported on an excerpt from Walter Isaacson’s upcoming biography “Elon Musk,” later published by The Washington Post, that said the billionaire had ordered the deactivation of Starlink satellite service near the coast of Crimea last September to thwart the Ukrainian attack. The excerpt said that Mr. Musk had conversations with a Russian official that led him to worry that an attack on Crimea could spiral into a nuclear conflict.

Later on Thursday, Mr. Musk responded on his social media platform to say that he hadn’t disabled the service but had rather refused to comply with an emergency request from Ukrainian officials to enable Starlink connections to Sevastopol on the occupied Crimean peninsula. That was in effect an acknowledgment that he had made the decision to prevent a Ukrainian attack.

“The obvious intent being to sink most of the Russian fleet at anchor,” he wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter. “If I had agreed to their request, then SpaceX would be explicitly complicit in a major act of war and conflict escalation.”

“How am I in this war?” The untold story of Elon Musk’s support for Ukraine:

Although he had readily supported Ukraine, he believed it was reckless for Ukraine to launch an attack on Crimea, which Russia had annexed in 2014. He had just spoken to the Russian ambassador to the United States. (In later conversations with a few other people, he seemed to imply that he had spoken directly to President Vladimir Putin, but to me he said his communications had gone through the ambassador.) The ambassador had explicitly told him that a Ukrainian attack on Crimea would lead to a nuclear response. Musk explained to me in great detail, as I stood behind the bleachers, the Russian laws and doctrines that decreed such a response.

Throughout the evening and into the night, he personally took charge of the situation. Allowing the use of Starlink for the attack, he concluded, could be a disaster for the world. So he secretly told his engineers to turn off coverage within 100 kilometers of the Crimean coast. As a result, when the Ukrainian drone subs got near the Russian fleet in Sevastopol, they lost connectivity and washed ashore harmlessly.

It’s ridiculous that Elon Musk’s private ownership of Starlink can unilaterally undermine Ukraine’s war effort. Musk’s actions put the true question of state versus market in existential terms.

Mykhailo Podolyak, Adviser to the Head of the Office of President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky:

Sometimes a mistake is much more than just a mistake. By not allowing Ukrainian drones to destroy part of the Russian military (!) fleet via #Starlink interference, @elonmusk allowed this fleet to fire Kalibr missiles at Ukrainian cities. As a result, civilians, children are being killed. This is the price of a cocktail of ignorance and big ego.

Elon Musk gave biographer top Ukrainian official’s private messages without permission. Mykhailo Fedorov says disclosure of exchange about military access to Starlink internet service “not pretty.

This is something of a complicated story, but I think we all agree that Elon Musk should not be making US defense policy, don’t we?

Now to business. Yesterday, to my surprise, I received this from Substack. I’ve never received this kind of email from them before:

Strangely—it’s a tribute to the civility of our comment section—I had not known that readers could report a comment. Nor had I known that if they did, I would be asked to adjudicate the comment’s fate. But on what grounds would I adjudicate it? I’ve never issued any kind of policy about what readers may say in our comments. It had never occurred to me to do so.

Oddly, too, given my preoccupation with Twitter’s terms of service, it had never occurred to me to check Substack’s terms of service. I found them here. The first thing that puzzled me was this:

The following guidelines outline what is and is not acceptable on Substack. We have the exclusive right to interpret and enforce these guidelines, although we may consult outside experts, research, and industry best practices in doing so.

If they have the exclusive right to interpret and enforce the guidelines, why am I being asked to do it? Perhaps they reviewed the comment and decided it was of no concern to them, but thought I should be aware that something had been reported to them?

Yet subsequently, they say:

These guidelines also apply to Substack comments, notes, and other community surfaces. We believe that writers are responsible for moderation their own communities as they see fit and readers for curating their own experiences on the platform.

So who’s responsible for this—them or me? Or both of us?

Apart from that, Substack’s terms of service are vague but reasonable-sounding:

In General

We want Substack to be a safe place for discussion and expression. At the same time, we believe that critique and discussion of controversial issues are part of robust discourse, so we work to find a reasonable balance between these two priorities. In all cases, Substack does not allow credible threats of physical harm.

Hate

Substack cannot be used to publish content or fund initiatives that incite violence based on protected classes. Offending behavior includes credible threats of physical harm to people based on their race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, disability or medical condition.

Fair enough. They continue by prohibiting doxxing, plagiarism, spam, phishing, porn, and impersonating someone else. Finally, they prohibit the promotion of “harmful and illegal activities.”

We don’t allow content that promotes harmful or illegal activities, including material that advocates, threatens, or shows you causing harm to yourself, other people, or animals.

“Illegal” has a clear meaning, although they don’t specify the jurisdiction. “Harmful?” Not so much. Substack gives all manner of anti-vaxxers a platform, for example, even though eschewing routine vaccines is demonstrably harmful. They leave the word “harmful” undefined, and as far as I can tell, it has no meaning, or at least, none I that I can derive from their behavior. I imagine that what they really meant to say is something like this: “We don’t permit content that will elicit such widespread moral revulsion that our brand and profits would be harmed by our association with it.”

They also say that you can’t make money on Substack if you’re barred from using Stripe, Substack’s payment-processor. Stripe’s terms of service have a bit more bite. Stripe may “immediately suspend” service to you if:

(a) Stripe believes it will violate any Law, Financial Services Terms or Governmental Authority requirement;1 …

(h) … Stripe believes that you are engaged in a business, trading practice or other activity that presents an unacceptable risk to Stripe; or

(i) Stripe believes that your use of the Services (i) is or may be harmful to Stripe or any third party; (ii) presents an unacceptable level of credit risk; (iii) increases, or may increase, the rate of fraud that Stripe observes; (iv) degrades, or may degrade, the security, stability or reliability of the Stripe services, Stripe Technology or any third party’s system (e.g., your involvement in a distributed denial of service attack);

(v) enables or facilitates, or may enable or facilitate, illegal or prohibited transactions; or (vi) is or may be unlawful.

The guidelines boil down to, “If we think you’re a crook or if you even look like a crook, you’re out of here. And don’t embarrass us.” Effectively, they reserve the right to cancel your service at will, and of course, they have the perfect right to do so. Indeed, they may have an obligation (to their shareholders) to do so.

Clearly, these are nothing like assurances that Substack and Stripe will go to the mat to protect your right to say what you please on this platform. Of course not. Substack and Stripe are businesses, not the US Constitution. What’s more, both are global business, so of course they make nothing like a promise that if your speech is protected by the US First Amendment, you may publish it on Substack. Why would they?

Neither Substack’s policy nor Stripe’s represent a violation of the First Amendment—nor, and this is important, of its spirit. The Constitution protects Substack’s right to associate, or not associate, with whomever they choose. Imagine a world in which it didn’t. What if the State of Nevada, say, passed a law obliging Arby’s to post these words on its front door: “Arby’s: We urinate in your food.” Whose rights would be violated? Under the US Constitution, it’s as clear that you may not be compelled to say something you don’t wish to say as it is that you may not be compelled to stop saying something.

Individuals, and private companies, decide a million times a day not to say something they find repellent or harmful to their business. Likewise, we all make a million decisions a day not to associate with people with whom we don’t wish to associate ourselves. Nothing in the Constitution compels me to promote Ken Opalo and Stormy Daniels equally. I have no interest in Stormy Daniels’ assessment of the coup in Ghana; neither do you; and it would be harmful to my business to promote her views every time I promote Ken Opalo’s.

Nor does the First Amendment compel Twitter to promote the views of scoundrels, nor does it suggest that there is something morally valuable in promoting them. A scoundrel’s right to say what he pleases does not extend to forcing or even encouraging Twitter to publish, echo, or amplify what he says.

The First Amendment does protect Elon Musk’s right to turn what is now his private property into an antisemitic pigsty. It also protects the ADL’s right to call for an advertiser boycott in response. It protects the right of advertisers to respond—or not respond—to that call as they see fit. This is all part of the normal exercise of speech and property rights in a liberal democracy. It has long been so.

Dior cannot be forced to use only very ugly people in its advertising. If Dior chooses to use very ugly people in its advertising, it is my right to say, “Goodness, I wouldn’t want to buy that Dior dress, the woman wearing it looks like a manatee.” It is not my right to have the words, “If you wear Dior, you’ll look like a sea cow” painted on Dior’s catwalk, or attached to their model’s vasty rear end. All of this is so basic that one senses bad faith in those who protest that Elon Musk is merely securing free speech for Nazis and the rest of us ought not object because it violates the Nazis’ rights—if not strictly in terms of the Constitution, at least in terms of its spirit.

These were, more or less, the sentiments expressed in the comment reported to Substack and then relayed to me. I did not realize that by issuing a verdict—I let the comment stand—I would lose access to the text of the complaint, so unfortunately I can’t cite it verbatim. But it was something to the effect of, “This guy is obviously writing this in bad faith and it’s annoying as hell to see his opinions every time we read the comments.”

I won’t be coy here: We all know he was speaking of WigWag. I let the comment stand, even though I agree with the reproach, for the following reasons:

I’ve never issued rules about what may or may not be said in the comments, so it would be unfair spontaneously to enforce these rules, particularly with no explanation. Lex retro non agit.

Although I too rolled my eyes at the comment, I didn’t think it so offensive that it would be harmful to my conscience or my business to be associated with it. I could change my mind if more evidence presented itself that WigWag’s presence was driving away my other readers, but I doubt it.

I think WigWag’s presence here benefits us. He’s an authentic avatar of an ideology to which I—and most of my readers—stand opposed. He’s probably one of the most articulate ones they’ve got. Why not hear him out, in case we’re missing something? He regularly reminds me of the way things look from the perspective of my political opponents (as opposed to caricatures of those opponents). That should be valuable to me. It’s better for the intellect to hear the best arguments your adversaries can make against your views than it is to have a pack of sycophants agreeing with your every word. (If you doubt that, look at what’s happened to so many figures in the public eye who clearly write with the aim of pleasing a roaring crowd and who never suffer themselves to be interrogated by those who disagree: It has made them irrepressibly stupid.)

I don’t think WigWag’s arguments are any good, in this instance. But let him keep trying, I say. He does, on occasion, offer a view I hadn’t considered, and when his arguments are bad, it reassures me that mine are correct. He speaks for a great many of my fellow citizens, to judge from the polls, and for some 60 percent of our readers, he speaks for our fellow citizens. It seems both intellectually unhygienic and an act of civic bad faith to refuse even to consider his perspective.

As for his comments being annoying, here is our new, official policy: If a tedious and tendentious bore makes the same bad-faith arguments in the comments over and over, readers are urged to indicate their displeasure by replying, “Parklife!”

That seems a more condign response than deleting the comment in question, and it might encourage the bore to realize he’s just being a bore—and to up his game.

Furthermore,

I find it admirable that WigWag, despite his passionately-held views, pays for and diligently reads a publication largely devoted to espousing views contrary to his own. I’ve often wondered why, if he so disagrees with me, he’s among my most faithful readers. Perhaps he finds it useful to subject his own views to challenge? If so, should we not encourage that, both because it’s a noble impulse and because his views are wrong? After all, perhaps we can persuade him he’s wrong. It’s not a lost cause. He’s paying to read what I have to say, after all. Some part of him must be tempted by the bright, shining light.

I also think it rather brave of him consistently to confront a large number of people who disagree with him. It takes some kind of moxie to be the lone voice willing to argue there’s not a thing wrong with the eager promotion of Nazism, right? Even if I think his views about this are utterly idiotic, a man willing to wade into an enraged crowd and defy it should be credited, at least, with having a mind of his own.

There’s another way WigWag adds value to this newsletter rather than detracts from it. Though I don’t always have time to read or respond to what he has to say, on occasion I’ve written whole essays in response to his comments simply because he’s annoyed me so greatly. I value anything that motivates me to work. On the days when a blank page is staring at me and I feel no special urge to say anything, a bit of irritation (or a lot of it) can serve to get my lazy ass into gear.

That’s why I adjudicated as I did. His comment may stand. Go ahead and Parklife the hell out of it, though.

Our New Comment Guidelines

Since it would be good to be able to appeal to published guidelines if ever I do decide to censor someone, here are our new guidelines:

I’ll censor anyone who crosses the line from “annoying” to “disgusting.” By “disgusting,” I mean, “I would not want my late grandmother to know I’m associated in any way with someone who would say such a thing.”

Feel free to report any comment you think rises to that level. I don’t always see all the comments, especially if someone leaves it long after an article’s been published, so that might be helpful to me. (I do try to read and respond to as many as I can.) If it’s disgusting, I will get rid of it. If it’s merely annoying, I’ll Parklife it. This will indicate that I’m on your side, in spirit, but that the comment doesn’t strike me as so wildly offensive that I should hammer it out of existence.

Among the things you’re paying for, if you subscribe, is the right to tell me how very wrong I am. Enjoy it!

Don’t abuse other subscribers. This has so far never been an issue, but it would bother me greatly if it were to happen.

Don’t be a crashing bore. People subscribe to CG for a more intelligent conversation than they’d have elsewhere. Be cordial, do not insult other readers, and don’t harm my business. If you threaten my bottom line, I will ruthlessly extirpate you.

That said, you are specifically prohibited from telling me that I’d have more subscribers if I agreed with you or warning me that I’ll lose subscribers if I refuse to say what you want me to say. The suggestion that I would abandon my deeply-held principles or a well-reasoned view for the price of a few subscriptions on Substack is odious.

I’m not utterly inflexible, however. If you’re willing to offer me real money to abandon my principles, we can talk.

Do not insult me by lowballing your opening bid.

These terms of service weren’t reviewed by a grammarian or a good proofreader. Obviously, the pronoun “it” here refers to “what you do.” That’s clearly what they meant, anyway. But in fact, “it” refers to “immediate suspension,” and if that isn’t immediately obvious to you, ask yourself what “it” refers to in these grammatically similar sentences:

“I’ll do anything you ask if it helps.”

“He’ll tell his girlfriend not to come to the wedding if it makes you feel better.”

“You can’t take the day off if it means we won’t meet our deadline.”

So effectively, Stripe says it may immediately suspend users if it will violate the law. The suspension itself, in this sentence, is what would violate the law.

This sort of thing makes me go half mad. It’s so garbled! Why didn’t they see that?

In 1978, a group of Neo-Nazis announced their intention to assemble and march in Skokie, Illinois, a community that was home to a number of survivors of the Shoah.

At great risk to its reputation and financial security, the ACLU offered to defend the fascist group; a decision that led to remarkable consternation amongst many of its members. The ACLU did the right thing.

The ACLU justified its decision by pointing out that the same laws it cited to defend the Neo-Nazi’s rights to free speech and assembly were precisely the same laws the organization used to defend the right of civil rights groups to assemble and march in the south despite the suggestion that allowing these groups to march could lead to violence.

It is almost certain that the ACLU would make a different decision today. The ACLU is a fundamentally different organization today than it was then. People of good will can differ about which version, the old or the new, they prefer. I prefer the older version.

Like the ACLU, the ADL is a very different organization with very different aspirations than it had at its founding. In my view, the current version of the ADL has lost its way so completely that it is a mere shadow of its former self. I don’t think Musk’s lawsuit has a snowball’s chance in hell of succeeding, but if by some miracle it did, and the ADL was financially ruined, I don’t believe it would be missed.

Ironically, if the ACLU was presented with the case of the Neo-Nazis in Skokie today and it decided to defend their right to march, I think it’s almost certain that today’s ADL would lambast the ACLU as a hate group. That’s how far American democracy and civil discourse has deteriorated.

It is true that Elon Musk’s Twitter is not bound by the First Amendment, but Musk has stated that his goal for Twitter is to serve as a global public square. To facilitate that, he rightly wants to keep censorship to a minimum and he doesn’t want to employ cadres of employees who’s job it is weed out bigoted tweets no matter how despicable. I think Musk is right; once you empower the censors, their mandate inevitably expands and the censorship regime becomes all-encompassing. We know this is true because it’s precisely what happened with pre-Musk Twitter, especially with American intelligence agencies and the FBI intimidating Twitter’s censors to eliminate content the Government didn’t like.

Putting up with the availability of bigoted comments (that no one needs to read) is a small price to pay for the creation of a forum where all opinions can be expressed. Cancel culture is bad; the censors are always the bad guys, never the good guys.

Claire, there are more Substacks and online publications where my views are in the majority than I can shake a stick at. I read some of them but I comment at none of them. The Cosmopolitan Globalist is the only site where I write comments. Partly it’s because I don’t want to spend my entire life writing comments; I mostly do it for the fun of it. More importantly, it’s far more interesting to engage people that I disagree with than I agree with.

Although I disagree with you and some of your readers about many things, a major reason I subscribe is because your writing is so good; brilliant, actually.

The commenters here are great. The worst comment section in the country, in my view, is the Washington Post's. The level of hatred is truly troubling.