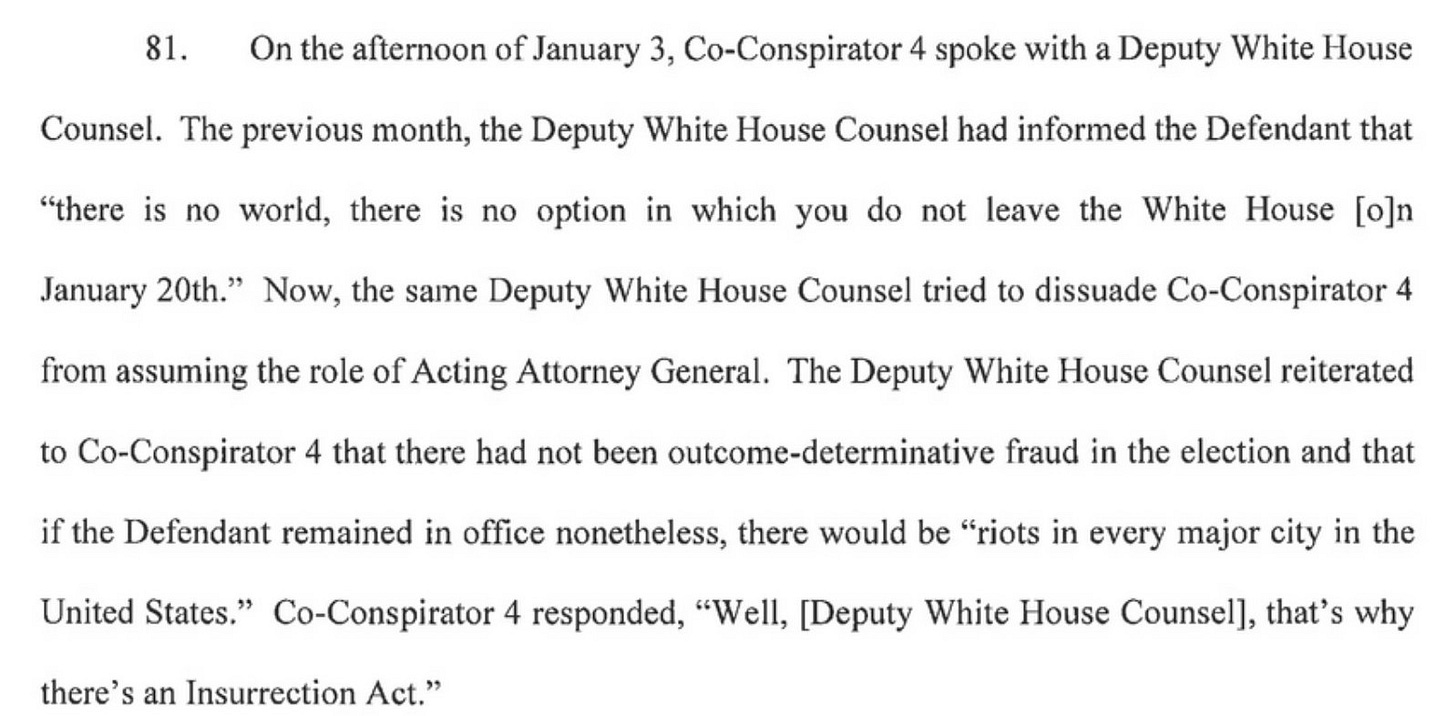

Trump has been indicted, at last, for his most grievous crimes. The indictment tells us little we didn’t already know from the January 6 Committee’s hearings, but there is one detail we didn’t know:

Trump once spoke admiringly of the Chinese government’s massacre of the students in Tiananmen Square. His 1990 interview with Playboy is notable for a many reasons, including his asseveration that the United States in 1990—then at the apex of its global prestige, unchallenged, by far the most powerful country the world had ever seen—was “going to hell.”

You have taken out full-page ads in several major newspapers that not only concern US foreign trade but call for the death penalty, too. Why?

Because I hate seeing this country go to hell. We’re laughed at by the rest of the world. In order to bring law and order back into our cities, we need the death penalty and authority given back to the police. … I take out those ads to wake up the government about how Japan and others are ripping our country apart ….

The whole interview reveals his character, but when I read of these plans to unleash the US military on American citizens, that interview and this passage came to mind:

What were your other impressions of the Soviet Union?

I was very unimpressed. Their system is a disaster. What you will see there soon is a revolution; the signs are all there with the demonstrations and picketing. Russia is out of control and the leadership knows it. That’s my problem with Gorbachev. Not a firm enough hand.

You mean firm hand as in China?

When the students poured into Tiananmen Square, the Chinese government almost blew it. Then they were vicious, they were horrible, but they put it down with strength. That shows you the power of strength. Our country is right now perceived as weak … as being spit on by the rest of the world—

It’s important that Trump was indicted. But I have a terrible feeling that it’s too late. That I’m watching the inexorable unraveling of a 245-year-old democracy that has been, for more than a century, the most important nation in the world.

The institutions that once seemed to me as solid and enduring as the laws of physics are not, it seems, strong enough to contain a demagogue. Even if Trump falters, another one will come along soon. Too many have now seen that it’s possible.

Americans now hate each other. John Gottman, of the famous Gottman love lab at the University of Washington, observed thousands of married couples and concluded that one trait, above all, foretold divorce, and that was contempt. By counting their contemptuous gestures and expressions, Gottman claimed, he could predict with 93 percent accuracy which marriages will survive.

It seems to me this must also be true of democracies. A nation, as Benedict Anderson famously suggested, is an imagined political community—imagined because we will never know most of the other members of this community, or even learn their names, “yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.” This fraternity is what allows us to kill and die for one another.

It is now absolutely common in American discourse to refer to other Americans as “the enemy.” Not “our opponents,” but “the enemy.” I can’t even look at Twitter—oh, excuse me, ex—without stumbling across someone luxuriating in the thought of killing other Americans.

There’s simply an unbridgeable difference between Americans who think what Trump did was an unforgivable crime and those who think it was no crime at all, or a minor crime compared to the decades of injury to which they believe they have been subjected.

I think we’re on the path to hell.

I’ve read two essays in the past few days that make, I think, a good effort to explain the rage of Trump’s supporters. Neither make new arguments—we’ve been discussing the points they raise for years—but they evoke them well. The first, by David Brooks, was published in The New York Times. The headline: What if we’re the bad guys here?

… I ask you to try on a vantage point in which we anti-Trumpers are not the eternal good guys. In fact, we’re the bad guys.

This story begins in the 1960s, when high school grads had to go off to fight in Vietnam, but the children of the educated class got college deferments. It continues in the 1970s, when the authorities imposed busing on working-class areas in Boston, but not on the upscale communities like Wellesley where they themselves lived.

The ideal that “we’re all in this together” was replaced with the reality that the educated class lives in a world up here, and everybody else is forced into a world down there. Members of our class are always publicly speaking out for the marginalized, but somehow we always end up building systems that serve ourselves.

The most important of those systems is the modern meritocracy. We built an entire social order that sorts and excludes people on the basis of the quality that we possess most: academic achievement. Highly educated parents go to elite schools, marry each other, work at high-paying professional jobs and pour enormous resources into our children, who get into the same elite schools, marry each other and pass their exclusive class privileges down from generation to generation.

The second, by George Packer, argues that America has fractured into four parts, which he calls “Free America,” “Smart America, “Real America,” and “Just America.”1

“Free America” could be described, roughly, as libertarian. “Smart Americans” are meritocrats. “Real Americans” are MAGA. “Just Americans” are the woke. The Free and the Real are yoked together in the GOP; the Smart and the Woke form the Democrats. It is a useful if imperfect taxonomy.2

All four narratives are also driven by a competition for status that generates fierce anxiety and resentment. They all anoint winners and losers. In Free America, the winners are the makers, and the losers are the takers who want to drag the rest down in perpetual dependency on a smothering government. In Smart America, the winners are the credentialed meritocrats, and the losers are the poorly educated who want to resist inevitable progress. In Real America, the winners are the hardworking folk of the white Christian heartland, and the losers are treacherous elites and contaminating others who want to destroy the country. In Just America, the winners are the marginalized groups, and the losers are the dominant groups that want to go on dominating.

“Real America,” he writes, “is a very old place,” and it has “always needed to feel that both a shiftless underclass and a parasitic elite depend on its labor.” His description of the plight of Real Americans is, however, sympathetic. They are the victims, in his view, of the various dogmas of the Free and Smart Americans. The Free Americans allowed untrammeled capitalism to destroy their way of life, and the Smart Americans told them they deserved it:

The disappearance of secure employment and small businesses destroyed communities. The civic associations that Tocqueville identified as the antidote to individualism died with the jobs. When towns lost their Main Street drugstores and restaurants to Walgreens and Wendy’s in the mall out on the highway, they also lost their Rotary Club and newspaper—the local institutions of self-government. This hollowing-out exposed them to an epidemic of aloneness, physical and psychological. Isolation bred distrust in the old sources of authority—school, church, union, bank, media. …

Bill Clinton’s presidency, in his account, was the high water mark of Free America—the moment when, on matters of economic policy, Smart America conceded. A new consensus now reigned: free trade, deregulation, and economic concentration were inevitable. Both parties agreed. Packer clearly thinks this was untrue, although his is not an essay about economic policy.3

Smart Americans correctly understood that in such a system, only the highly educated would flourish. I believe he’s correct: Policy makers such as the Clintons envisioned the transformation of the United States into something like a massive Singapore—technologically advanced, financially sophisticated, with a highly skilled and educated citizenry. The America that would emerge, they believed, would not be one of formerly-unionized carmakers shoveling burgers at minimum wage and urinating in bottles at Amazon fulfillment centers. Those dislocated by globalization and liberalization would learn to code.

Adherents to this vision grossly overestimated Real America’s willingness—and more important, its ability—to adapt. Packer does not dwell on it, but I agree this was the key mistake: underestimating the cognitive demands of employment in a post-industrial economy and overestimating the public’s aptitude for the requisite skills.

In Packer’s telling, Smart Americans thereafter focused on getting their kids into the best schools and otherwise withdrew from civic life, contemplating those who lost, under the new economic dispensation, with meritocratic cruelty: The losers, the meritocrats told themselves, had no one to blame but themselves.

Packer focuses on the elite’s perpetuation of itself by means of education:

A system intended to give each new generation an equal chance to rise created a new hereditary class structure. Educated professionals pass on their money, connections, ambitions, and work ethic to their children, while less educated families fall further behind, with less and less chance of seeing their children move up. By kindergarten, the children of professionals are already a full two years ahead of their lower-class counterparts, and the achievement gap is almost unbridgeable.

He does not mention, because it is unmentionable, the most important thing educated professionals pass on to their children: their genes. This is the heart of the problem, but one he’s unwilling to discuss forthrightly. Like good looks, intellectual aptitude is strongly hereditary. If the elevator from the working class to the elite ceased working, as he argues, some time in the 1970s, I suspect it is less because the elite is keeping the working class down through their connections and money and more due to a trend that is much harder to fix through any policy remedy: assortative mating.

It was once common for highly intelligent men to marry their rather less gifted secretaries. But when educational and professional opportunities opened for women, the most able of them quickly moved up the professional ladder. Women do not like to date down. These women married the most able men. If their children are two years ahead of their lower-class counterparts by kindergarten, it is probably not because their parents have gamed the system, nor is it because of their parents’ money and connections, either. These kids are just smarter. No one wants to face this because no one has the faintest idea what to do about it.

Packer is right to discern that we have created an economy that suits only the cognitive elite, and right to say that in describing it as a meritocracy, we’ve given the smart permission to blame the dumb for their plight. It is cruel. Where noblesse once obliged, it now taunts the (formerly) working class by telling them to leave those benighted Appalachian villages already, and for the love of God, stop buying Pepsi and fentanyl with your food stamps.

The plain truth is that most people are not capable of academic achievement. It is my view, however, not Packer’s, that Thatcher was probably right: There was no alternative to economic liberalization. It was inevitable that as the rest of the world went through the Industrial Revolution, American factories would cease to dominate the global economy. Its unionized car workers would not be able to compete with low-wage workers overseas. Packer seems to think otherwise, but does not say why. If he is right that it was never realistic to imagine that every American would become an educated, white-collar worker, his suggestion that the Democratic Party should have “refused to accept the closing of factories in the 1970s and ’80s as a natural disaster” and “become the voice of the millions of workers displaced by deindustrialization and struggling in the growing service economy” is facile. What would he have had the Democrats do—nationalize those factories? He may well have a good answer to that question. I am open to it if he does. But I can’t figure out how the United States could have been spared deindustrialization absent an almost Soviet commitment to a planned economy.

If the Democrats were guilty, they were guilty of a delusional faith in the human capacity for self-improvement. Real America, they should have grasped, would not readily be re-skilled to take new pride of place at the global vanguard of the Information Age. Whether or not this problem was, in principle, soluble, he and I agree that it was not solved.

By the time Palin talked about “the real America,” it was in precipitous decline. The region where she spoke, the North Carolina Piedmont, had lost its three economic mainstays—tobacco, textiles, and furniture making—in a single decade. Local people blamed NAFTA, multinational corporations, and big government. Idle tobacco farmers who had owned and worked their own fields drank vodka out of plastic cups at the Moose Lodge where Fox News aired nonstop; they were missing teeth from using crystal meth. Palin’s glowing remarks were a generation out of date.

This collapse happened in the shadow of historic failures. In the first decade of the new century, the bipartisan ruling class discredited itself—first overseas, then at home. The invasion of Iraq squandered the national unity and international sympathy that had followed the attacks of September 11. The decision itself was a strategic folly enabled by lies and self-deception; the botched execution compounded the disaster for years afterward. The price was never paid by the war’s leaders. As an Army officer in Iraq wrote in 2007, “A private who loses a rifle suffers far greater consequences than a general who loses a war.” The cost for Americans fell on the bodies and minds of young men and women from small towns and inner cities. Meeting anyone in uniform in Iraq who came from a family of educated professionals was uncommon, and vanishingly rare in the enlisted ranks. After troops began to leave Iraq, the pattern continued in Afghanistan. The inequality of sacrifice in the global War on Terror was almost too normal to bear comment. But this grand elite failure seeded cynicism in the downscale young.

The financial crisis of 2008, and the Great Recession that followed, had a similar effect on the home front. The guilty parties were elites—bankers, traders, regulators, and policy makers. Alan Greenspan, the Federal Reserve chairman and an Ayn Rand fan, admitted that the crisis undermined his faith in the narrative of Free America. But those who suffered were lower down the class structure: middle-class Americans whose wealth was sunk in a house that lost half its value and a retirement fund that melted away, working-class Americans thrown into poverty by a pink slip. The banks received bailouts, and the bankers kept their jobs.

He is on much more solid footing here. Two failed wars and a financial crisis were not a great advertisement for meritocracy.

Packer’s argument is far more detailed than Brooks’, but both are making the same point. We’ve created a system in which only the highly educated can flourish and only the children of the highly educated follow in their footsteps. We have immiserated the rest. Their communities were destroyed—either by our foolish economic policies, in Packer’s view, or by economic forces far bigger than any of us, in mine. We sent them to get their asses blown off in wars we weren’t ourselves prepared to fight. After superintending over their precipitous economic decline, we despised them for their poverty, called them hicks, and then—the final straw—our kids emerged from the elite universities (to which they had no access) ceaselessly castigating them as white supremacists and proposing literally to castrate their kids. No wonder, they both suggest, that this cohort doesn’t give a damn if Trump tried to stage a coup.

This point of view is also well-represented among readers of the Cosmopolitan Globalist. I have no patience for it. I do have a great deal of patience for these complaints. But I have no patience for the remedy. When I hear the apologies for Trump, I feel as if I’m listening to a man describe his miserable marriage. “She cheated on me for years,” he says.

“That’s awful,” I say sincerely.

“Told me I was a loser because I didn’t make enough money.”

I wince. “I’m so sorry.”

“Then she divorced me and took the kids. She turned them against me. They don’t talk to me now.”

“What a bitch!”

“And she took every penny I had.”

“God! No wonder you’re depressed.”

“So I killed her.”

Our arguments have the dreadful repetitive quality they do because, contrary to what is often asserted, we don’t truly disagree about the facts. Whatever they say, Trump’s supporters cannot really believe this indictment is the process of a “politicized judiciary.” These charges are not a mystery. We all saw what happened. If you think such a thing so trivial that you would vote for Trump again, we don’t differ about the facts, we differ in our values.

Differences about policy can be bridged, finessed, overlooked. We can agree to disagree. We can pretend to respect one another’s views. But we can’t pretend to respect one another about this. This column by Tom Nichols, published the other night in the Atlantic, is deeply disturbing because he put this so plainly:

… Long before now, however, Americans should have reached the conclusion, with or without a trial, that Trump is a menace to the United States and poisonous to our society. … The GOP base, controlled by Trump’s cult of personality, will likely never admit its mistake: As my colleague Peter Wehner writes, Trump’s record of “lawlessness and depravity” means nothing to Republicans. But other Republicans now, more than ever, face a moment of truth. They must decide if they are partisans or patriots. They can no longer claim to be both.

The rest of us, as a nation but also as individuals, can no longer indulge the pretense that Trump is just another Republican candidate, that supporting Donald Trump is just another political choice, and that agreeing with Trump’s attacks on our democracy is just a difference of opinion. (Those of us who share our views in the media have a particular duty to cease discussing Trump as if he were a normal candidate—or even a normal person—especially after today’s indictment.) I have long described Trump’s candidacies as moral choices and tests of civic character, but I have also cautioned that Americans, for the sake of social comity, should resist too many arguments about politics among themselves. I can no longer defend this advice. … every American citizen who cares about the Constitution should affirm, without hesitation, that any form of association with Trump is reprehensible, that each of us will draw moral conclusions about anyone who continues to support him, and that these conclusions will guide both our political and our personal choices.

But where does that leave us? The MAGA movement amounts to about a quarter of the American population. They’re not just going to disappear.

Polls now suggest that Biden and Trump are now in a dead heat.

As of now, more than half of the GOP’s primary voters say they will vote for Trump.

So as many as one in four Americans have, in a sense, seceded—or worse, because they want to impose their obviously minority government on the rest. Another fifteen percent, perhaps, are willing to follow them. And the others loathe them for it. As of last April, only 24 percent of the American public viewed the MAGA movement positively. Even the Black Lives Matters movement ranked considerably higher:

The peculiarities of the American electoral system, however, and Joe Biden’s weakness, mean there’s a very real chance Donald Trump will win. And I simply can’t see how the United States would survive this. A significant portion of electorate, knowing that Trump would have seized power in a coup and shot them in the streets, will not view him as legitimate even if he wins fair and square. If he loses, he will never concede. If he needed to win last time to slake his insatiable narcissism, he now needs to win to avoid dying in prison. Is there any limit to what he would do to return to power? I doubt it. And Trump’s election isn’t just Trump’s only hope of survival, but Putin’s, too. How will a weakened America survive this combination?

I just don’t see how, with this malevolent, wolfish, supremely dangerous presence looming over everything, the United States remains a stable country. Violence now seems inevitable. Possibly terrible violence. Everyone knows it. But no one knows what to do. Like the threat posed by artificial intelligence, the danger is accelerating faster than any solution we can imagine.

We all know, too, that Joe Biden is not the man to confront this threat. He is not senile, but he is too old. He gets confused easily. He can’t focus sharply. Above all, he has lost his ability to speak fluently. Without that, he cannot forthrightly describe the danger; he cannot inspire; he cannot reassure. He offers a series of flabby, stuttered clichés.

By contemporary standards, Joe Biden may be reckoned an okay president. There’s something sort of reassuring about his pretense of politics as usual. But the moment requires anything but politics as usual—and there is no one capable of offering it. There is no genius of politician, like FDR, waiting in the wings. There is no one with the force of personality to reaffirm our central commitment to democracy.

If Biden loses to Trump, there will be no Ukraine. Europe will be plunged into a nightmare I find too frightening to contemplate.

Do Americans realize that once you lose your reputation for political stability, your wealth disappears?

How thrilled the ayatollahs must be, watching the Great and Little Satans simultaneously tearing themselves apart.

In 1817, German students organized a pilgrimage to Wartburg, then a hotbed of German nationalism. There, they declared their universities would accept neither foreign students nor Jews. They built a bonfire and burned the books of writers who opposed German unification.

Throughout Heinrich Heine’s work there is a horror of the reactionary stupidity of the Prussian regime and its militarism, its philistine patriotism and antisemitism, the megalomania of German nationalism. Heine was, of course, Jewish.

Heine’s first play, Almansor, is set in Granada in 1492, and depicts the burning of the Quran. It is unclear why he depicted Muslims as the victims of book burning and not Jews. The sentence now engraved before the Berlin Opera House—a warning everyone has come to know—comes from Almansor. “This was just a prelude. Where books are burned they will end up burning people.”

Perhaps you know Heine’s famous poem Nachtgedanken. He wrote the poem in 1844, a moment of pre-revolutionary ferment in Europe. He lived at the time in exile in Paris, his works having been censored and banned in Germany:

Denk ich an Deutschland in der Nacht, Dann bin ich um den Schlaf gebracht, Ich kann nicht mehr die Augen schließen, Und meine heißen Tränen fließen.

If you don’t recognize the poem in German, you may recognize the first lines in English:

When I think of Germany at night, It robs me of my sleep.

He could not have intended those words to be as sinister and dark as later they became; the enormity of Germany’s fate was unimaginable in 1844. But clearly he had a shudder of presentiment.

I am thinking about America.

As usual, this essay differs very slightly from the one subscribers received. I have corrected typos and one or two sentences that sounded less fluent, on re-reading, than I preferred.

It’s paywalled, I think. If you don’t subscribe and want a PDF, send me an email. It’s long but worthwhile.

I would have said before reading Packer that the US was divided in three parts: Normies, MAGA, and the woke, with normies making up about half the population and the crazies—who are not only batshit nuts but extremely violent—about evenly divided among the other half.

There is a limit to what any writer can achieve in a single essay, and I don’t fault Packer for failing to make his arguments here explicit.

David Brooks wrote pretty much of a rehash of his long-held convictions on class separation, but he was mostly wrong in this piece. MAGA people are not mostly uneducated second-class citizens. For proof, you only have to look at the H6 rioters. Many, if not most, were fairly well-off folks. Stewart Rhodes was a Yale-educated lawyer. There was that real estate agent who took a private plane. The list goes on. Tom Nichols has the type nailed down, and we need to read his stuff.

Between this depressing but brilliantly written piece and Andrew Sullivan’s (also depressing and brilliantly written) today, I would be on the verge of slicing my wrists if not for my innate optimism in a country that survived a civil war that set brother upon brother in an ultimately successful quest to expunge our original sin to eventually become the greatest power the world has ever seen. A country, I would add, that used that power not to subjugate its enemies but to empower them in a way the world had never experienced. Maybe my optimism is misplaced and I have come to see the future with the same selectiveness my wife insists I remember the past but I have watched my fellow Americans interact with each other all across this continent over the past few years and the divisions that seem so apparent online simply do not exist in the real world. Sure we have our problems and those problems are serious and occasionally expressed violently and Donald Trump is a real threat to our constitutional order but I refuse to believe this great nation will be brought down by a reality TV conman.