Middle East 101, Week IV

The War of Independence and the birth of the Palestinian refugee problem

Here’s the video of our discussion with Oren Kessler, which was absolutely terrific. He also sent me a message saying that if any of you would like an autographed copy of Palestine 1936, he has bookplate stickers that he can sign and mail to you. Just send him your address.

If you’d prefer to listen to the discussion, here’s the audio file. (Does anyone listen to these discussions? Do they make sense without the video? Should I keep posting them?)

Oren mentioned that he’d also written two separate articles about the secret testimony before the commission:

“A dangerous people to quarrel with,” which treats Lloyd George’s secret testimony to the Peel Commission in 1937. Lloyd George was the prime minister when the declaration was issued, so his is obviously the authoritative voice if you’re trying to understand why the British government made the declaration and how they intended it to be understood. As we discussed, this testimony and that of the other sixty witnesses before the commission were only recently declassified. It’s fascinating stuff. Lloyd George, Oren writes, was at once “Judeophobe and philo-Semite, militarist and appeaser, Zionist champion and Hitler enthusiast.”

Herbert Samuel’s secret 1937 testimony on the infamous mufti of Jerusalem. Newly revealed files show how Palestine’s first high commissioner—a Jew and a Zionist—defended tapping Amin al-Husseini and lamented that “Jews can be extremely irritating people.” (There’s a podcast with Oren on the same page that you might enjoy, too.)

“They are a very subtle race and they have means of communicating throughout the world which nobody seems to know about.”—Lloyd George

On land sales during the Mandate Period, Oren recommends Kenneth Stein’s book, “The Land Question in Palestine.”

Speak, Historiography

We now begin reading about the most bitterly contested event in the history of the conflict. Israel’s War of Independence is known, to Palestinians, as the Nakba—the catastrophe. Because the period is so critical, the reading list this week will be demanding. If the consensus favors it, we can take an extra week with this list, too: We’ll check in on Sunday to see how everyone’s getting on with it.

Start with these primary documents. Read the analysis so that you get the basic chronology, but keep in mind that their interpretation is hotly contested, as you’ll see below:

The History Wars

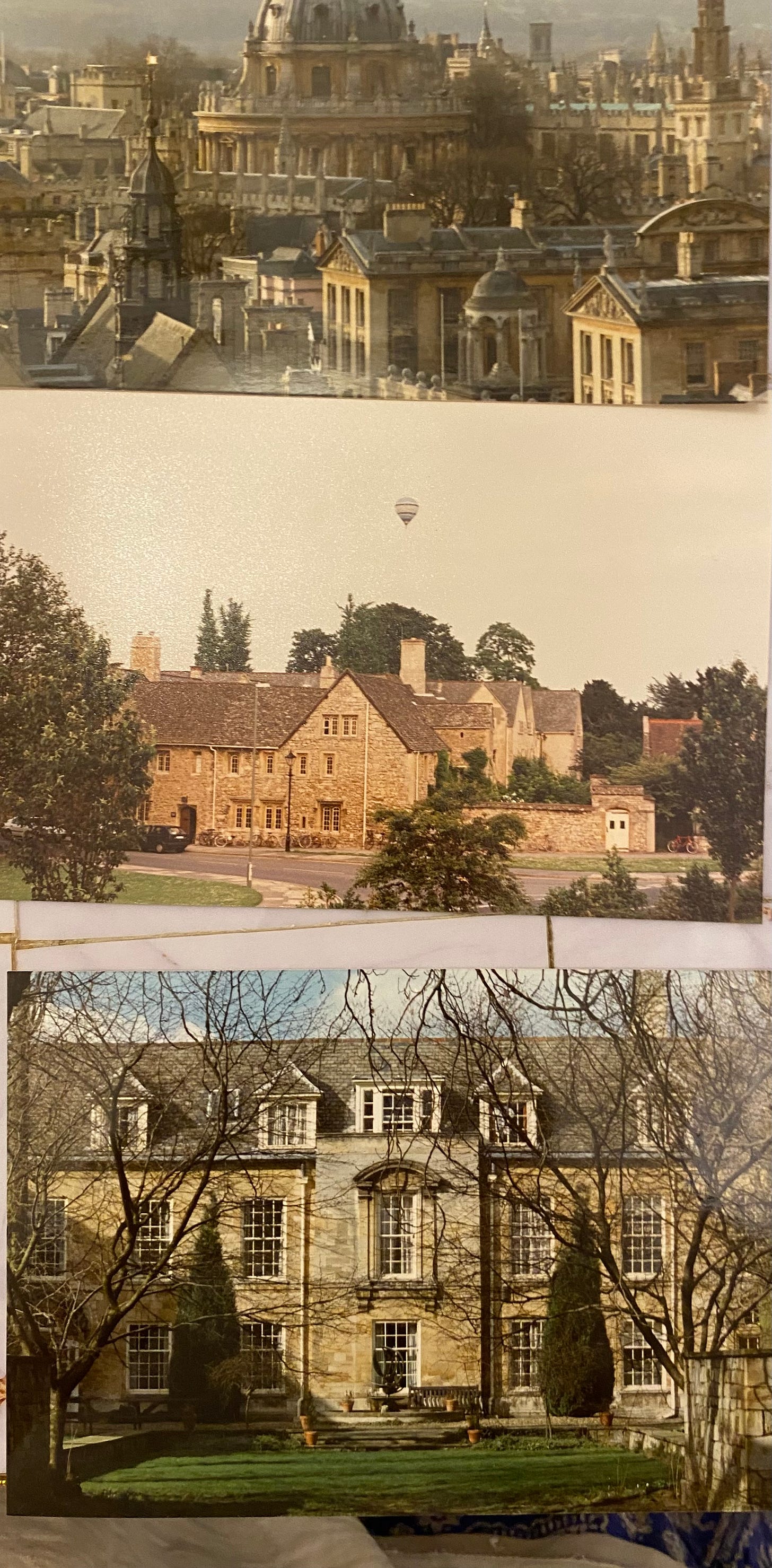

Let me now pass around a few sepia-tinged photos. This was Oxford University in 1991. (It was also Oxford University in 1470, or 1732, or 1928—it never changes.) The middle photograph shows the front view of Holywell Manor, the graduate annex of Balliol College. Below it is the Holywell Manor garden. You can’t see it, but my room is just to the right:

Judith and I met as graduate students at Oxford in 1991. We’d seen each other around before, but we didn’t get to know one another until we both found ourselves in the same seminar. As I subsequently wrote,

… We became friends walking back to Balliol College each week, along the leafy Banbury Road, from a seminar at St. Antony’s College on the international relations of the Middle East. Both secular American Jews—the only ones in the class—we found in one another a measure of intellectual and ethnic solidarity against our classmates, who tended to view the region through the prism fashionable in academia: The violence and misery of the Middle East devolve from Israeli territorial expansionism and its abuse of the Palestinians. Once when a suicide bombing in Israel claimed the lives of a number of children under the age of 10 — it is often forgotten how common an occurrence these were even during the Rabin years—a fellow student, upon hearing the news, proclaimed with satisfaction, “Good. They deserve it.”1

Leading the seminar was the Anglo-Israeli historian Avi Shlaim, who was also Judith’s thesis advisor. (He was also married to Lloyd-George’s great-granddaughter.) That was an especially interesting time to be in that seminar, because several years before, there had been a massive declassification of British, American, and Israeli archives under the thirty-year-rule. For the first time, historians were able to explore the records treating the War of Independence. Avi Shlaim was one of those historians. Benny Morris was another. Ilan Pappé was a third. What they found in those archives caused a historiographical earthquake. These researchers came to be called, with no special originality, the New Historians.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Cosmopolitan Globalist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.