From the Berghof to the Oval Office

Notes on the most shameful day in the history of the Republic

A man sits across from power. His fingers tighten around the arms of his chair.

The bully makes no effort to mask his contempt. He sits rigidly, eyes burning with an unnatural intensity, fingers twitching on the armrest of his chair. When he speaks, it is not a conversation but an eruption—words spat like bullets, contempt laced through every syllable.

The outburst does not abate. It is not a speech but an assault, designed not to persuade but to disorient, to cow, to humiliate. The bully leans forward, slamming his fists against the table. His face reddens, his voice sharpens. He moves from insults to threats, from history to grandiosity. The great country he leads will no longer be mistreated, he says. Those days are over. The people have had enough. His words are not arguments—they’re sentences, verdicts, pronouncements of doom.

“You are nothing,” says the bully, not quite shouting. One of his lackeys smirks. “You think you are independent? You are a failure, a disgrace.” Behind him, the immense generals stand silent, unmoving. They don’t need to speak; their presence says everything. The visitor looks at them and understands what is being offered. This is not diplomacy. It’s a choice between submission and annihilation.

The visitor is allowed no rebuttal. He does not speak until the torrent of invective slows, and even then, his words are weak, uncertain. He tries to protest, to insist that he and his country are not to blame, that he has done all he could to maintain peace. The bully’s response is bitter, scornful laughter, as if the very idea is absurd. He rises suddenly—pacing now, shaking his head, muttering to himself in a fevered rant. “You will sign, or we will act. You will agree, or you will cease to exist.”

There is no need to say what that means. The visitor has seen the faces of the men behind him. He knows that even if he signs, this meeting is not a negotiation but an autopsy. He has been given no options, only demands. If he yields, his nation dies slowly. If he resists, it dies swiftly. There will be no help coming.

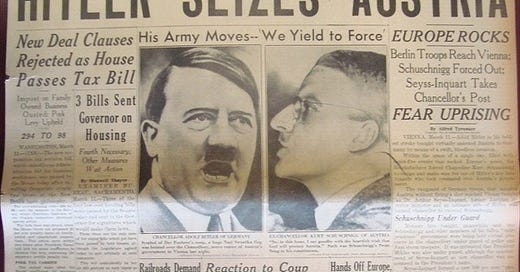

The year was 1938. The visitor was the chancellor of Austria, Kurt Schuschnigg. The bully was Adolf Hitler. The place was the Berghof, Hitler’s alpine retreat. Hoping to achieve a peaceful settlement with Hitler, Schuschnigg had agreed to a face-to-face meeting, arranged by the former ambassador to Austria, Franz von Papen. The meeting was a disaster. It marked the beginning of the end of Austrian independence, paving the way for the Anschluss that would occur weeks later.

In 1934, Austrian Nazis, who supported Hitler’s goal of incorporating Austria into the Third Reich, murdered Schuschnigg’s predecessor, Engelbert Dollfuss, in a failed coup d’état, badly destabilizing the country.

On August 19, 1934, President Hindenburg died of old age. Within hours, Hitler. unified the offices of President and Chancellor, took the title of Führer, and assumed control of the German armed forces. Over the months that ensued, Hitler bluffed, lied, threatened, and intimidated the leaders of Europe. At the time of the Berghof meeting, the Nazis were gaining ground in Austria, thanks to covert funding from the German Foreign Office.

William Shirer wrote, in The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich,

Throughout 1937, the Austrian Nazis, financed and egged on by Berlin, had stepped up their campaign of terror. Bombings took place nearly every day in some part of the country, and in the mountain provinces massive and often violent Nazi demonstrations weakened the government’s position. Plans were uncovered disclosing that Nazi thugs were preparing to bump off Schuschnigg as they had his predecessor. Finally on January 25, 1938, Austrian police raided the Vienna headquarters of a group called the Committee of Seven, which had been set up to bring about peace between the Nazis and the Austrian government, but which in reality served as the central office of the illegal Nazi underground. There they found documents initialed by Rudolf Hess, the Fuehrer’s deputy, which made it clear that the Austrian Nazis were to stage an open revolt in the spring of 1938 and that when Schuschnigg attempted to put it down, the German Army would enter Austria to prevent “German blood from being shed by Germans.”

Relations between Austria and Germany deteriorated. In January 1938, responding to Hitler’s threats, Schuschnigg made a public declaration:

An absolute abyss separates Austria from Nazism ... We reject uniformity and centralization. ... Catholicism is anchored in our very soil, and we know but one God: and that is not the State, or the Nation, or that elusive thing, Race.

On February 12, 1938, Schuschnigg travelled to Germany, accompanied by his foreign minister, Guido Schmidt, to confer with Hitler at his residence in the Bavarian Alps above Berchtesgaden, the Berghof.

Schuschnigg was 41 years old, a soft spoken, Jesuit-educated lawyer who, like his predecessor, led an authoritarian government. During the past years of instability and unrest in Central Europe, he had struggled to appease Hitler while protecting Austria’s independence, which he devoutly desired to safeguard.

Papen met Schuschnigg’s car at the border and joined him for the ride to the Berghof. Hitler was in a very good mood that morning, Papen said. Hitler hoped that Schuschnigg wouldn’t mind, he added, if three of Germany’s top generals were also present during the day’s discussion.

When he arrived at the villa, Hitler was waiting for him on the steps. Behind him were Wilhelm Keitel, Chief of the High Command; Air Force General Hugo Sperrle; and Walter von Reichenau, Commander of Army troops along the German-Austrian border. Throughout the day, Schuschnigg would not only be subjected to Hitler’s verbal onslaught but confronted with a silent, towering wall of military officers, chosen specifically for their height and menacing presence. Hitler choreographed his meetings obsessively to intimidate weaker opponents. He understood the psychological impact of body language, posture, and physical presence. All were taller than Schuschnigg and all stood without saying a word as Hitler ranted.

Hitler led Schuschnigg to the great hall on the second floor, where a large plate glass window overlooked the Alps. Schuschnigg attempted to break the ice with pleasantries about the view. Hitler abruptly cut him off: “We did not gather here to speak of the fine view or the weather.”

The ensuing discussion was, as Schuschnigg described it, “somewhat unilateral.” Hitler launched into a tirade against Schuschnigg and Austrian policies, shouting at the Chancellor, threatening and insulting him without respite: “You have done everything to avoid a friendly policy,” Hitler fumed:

The whole history of Austria is just one uninterrupted act of high treason. That was so in the past, and is no better today. The historical paradox must now reach its long-overdue end. And I can tell you here and now, Herr Schuschnigg, that I am absolutely determined to make an end of all this. The German Reich is one of the Great Powers, and nobody will raise his voice if it settles its border problems … Who is not with me will be crushed.1

Shocked, the quiet and well-mannered Schuschnigg sought to conciliate him, yet also to stand his ground. He differed, he said, on the matter of Austria’s role in German history. “Austria’s contribution in this respect is considerable—”

Hitler cut him off. “Absolutely zero. I am telling you, absolutely zero. Every national idea was sabotaged by Austria throughout history; and indeed all this sabotage was the chief activity of the Hapsburgs and the Catholic Church.”

Schuschnigg must surely have felt not only disturbed and intimidated, but unsure how one could possibly respond to something so absurd. “All the same, Herr Reichskanzler,” he tried, attempting to be as mollifying as possible, “many an Austrian contribution cannot possibly be separated from the general picture of German culture. Take, for instance, a man like Beethoven—”

“Oh, Beethoven? Let me tell you that Beethoven came from the lower Rhineland!”

“Yet Austria was the country of his choice,” protested Schuschnigg, “as it was for so many others.”

“That’s as may be. I am telling you once more that things cannot go on in this way. I have a historic mission, and this mission I will fulfill because Providence has destined me to do so ... Who is not with me will be crushed ... I have chosen the most difficult road that any German ever took. I have made the greatest achievement in the history of Germany, greater than any other German. And not by force, mind you. I am carried along by the love of my people ... ”

“Herr Reichskanzler,” said Schuschnigg, “I am quite willing to believe that.”

This continued for an hour. At last, attempting to calm him, Schuschnigg asked Hitler to enumerate his complaints. “We will do everything to remove obstacles to a better understanding,” he said, “as far as possible.”

“That is what you say, Herr Schuschnigg! But I am telling you that I am going to solve the so-called Austrian problem one way or the other.” He accused Schuschnigg of fortifying the Austrian border. Schuschnigg protested that he hadn’t done so.

“Listen!” Hitler barked at him, “You don’t really think you can move a single stone in Austria without my hearing about it the next day, do you?”

“I have only to give an order, and in one single night all your ridiculous defense mechanisms will be blown to bits. You don’t seriously believe that you can stop me for half an hour, do you? ... I would very much like to save Austria from such a fate, because such an action would mean blood. After the Army, my SA and Austrian Legion would move in, and nobody can stop their just revenge—not even I.”

Hitler repeatedly addressed Schuschnigg by his name, not his title—an astonishingly rude breach of diplomatic protocol. He reminded Schuschnigg that Austria was isolated and helpless. Austria, he hissed, was in a very bad position. It was in no position to negotiate. It was isolated diplomatically. It had no hope of repelling a Nazi invasion:

“Don’t think for one moment that anybody on earth is going to thwart my decisions. Italy? I see eye to eye with Mussolini ... England? England will not move one finger for Austria ... And France?”

Hitler reminded Schuschnigg that France could have stopped him in the Rhineland, but did nothing. “Now it is too late for France.”

“I give you once more, and for the last time, the opportunity to come to terms, Herr Schuschnigg. Either we find a solution now or else events will take their course ... Think it over, Herr Schuschnigg, think it over well. I can only wait until this afternoon.”

During this meeting, Hitler deliberately left Schuschnigg alone for extended periods to heighten his anxiety. At last, exhausted and broken, Schuschnigg asked Hitler what his terms were. Hitler cut him off. He dismissed him, saying. “We can discuss that this afternoon.” He departed for lunch and left Schuschnigg and his foreign minister in a small anteroom.

After Hitler’s lunch, the Austrians were escorted to meet Papen and Germany’s Foreign Minister, Joachim Ribbentrop, who presented Schuschnigg with the two-page document enumerating Hitler’s demands. These effectively called for him to turn his government over to the Nazis immediately.

Schuschnigg’s predecessor had banned the Austrian Nazi Party and imprisoned many of its members. They were to be freed, and the ban on the Nazi party was to be lifted. The Nazi sympathizer Arthur Seyss-Inquart was to be named minister of the interior and given full command over the police. Nazi sympathizers were to be named ministers of war and finance. Austria was to prepare for economic union with the Third Reich, and align its foreign and military policies with Germany’s. These were the Führer’s final demands, Ribbentrop told Schuschnigg. There would be no more negotiation. Sign immediately. Or else.

Under extreme duress, Schuschnigg told Ribbentrop he would consider signing. He asked for assurance that after this, there would be no further interference in Austria’s internal affairs. Ribbentrop assured him that provided all his demands were met, Hitler would respect Austria’s sovereignty.

When he wavered, Schuschnigg was escorted back to see Hitler, who was pacing back-and-forth in his study. Again, Hitler shouted:

“Herr Schuschnigg ... here is the draft of the document. There is nothing to be discussed. I will not change one single iota. You will either sign it as it is and fulfill my demands within three days, or I will order the march into Austria.”

Browbeaten and subjugated, Schuschnigg signed the document, but informed Hitler that only Austria’s president had the power to ratify it.

Hitler exploded. He demanded Schuschnigg guarantee its ratification. He “seemed to lose his self-control,” Schuschnigg later wrote. He rushed for the door and screamed for General Keitel. Schuschnigg was sent to a waiting room, left to wonder what the men were saying. It was a bluff: Keitel later told Papen that when he arrived to ask for orders, Hitler chuckled: “There are no orders. I just wanted to have you here.”

Half an hour later, Schuschnigg was ushered back in to see Hitler, who said, “I have decided to change my mind—for the first time in my life. But I warn you, this is your very last chance. I have given you three additional days to carry out the agreement.”

Schuschnigg departed Berchtesgaden accompanied by Papen, who was slightly embarrassed. “You have seen what the Führer can be like at times,” he said. “But the next time I am sure it will be different. You know, the Führer can be absolutely charming.”

Once safely back in Austria, Schuschnigg called for a national plebiscite to demonstrate Austrian resolve against German coercion. It was a desperate act. He wrongly believed Hitler would not risk an international incident.

The day before the vote, German troops marched into Austria. Schuschnigg was arrested. He and his wife were subsequently sent to Sachsenhausen, then Dachau.

Seyss-Inquart named himself both chancellor and president of Austria, even though the sitting president, Wilhelm Miklas, refused to resign. Hitler crossed the border soon thereafter, welcomed by rapturous crowds.

With the assistance of Himmler, Heydrich, and the Seyss-Inquarts puppet government, the Nazis embarked on a campaign of terror. Tens of thousands of Austrians, among them Catholics, Social Democrats, Socialists, Communists, and Jews, were arrested and sent to the concentration camps.

I believe what we saw earlier today in the Oval Office was the single most shameful moment in American history. There have of course been other shameful moments. We have betrayed our allies before. But never before have we done it while bullying and humiliating them in front of the entire world because we thought it would make “good television.” Never before have we turned the Oval Office into a spectacle so classless that even Tony Soprano would have vomited to see it. Never before have we done this for no reason but the benefit and pleasure of the murderous enemy of the United States who is chortling and dangling our president’s puppet strings. Never before have our leaders appeared so indescribably ignorant, so galactically self-absorbed, so petty and petulant, so obviously and dangerously unfit and unstable, so preposterous, and so menacing. Never before have they publicly betrayed us, declaring, before our eyes, their allegiance to an enemy who has been working incessantly to discredit our form of governance, reduce our power to insignificance, set us at each other’s throats, and murder us. Trump declared his allegiance to Putin publicly while his repulsive sidekick smirked and preened, and not one person in that room had the guts to say, “That’s enough, assholes. This is the People’s house.”

I have been trembling with anger at those despicable thugs since I saw that. Enough of apologizing for them, of equivocating, of normalizing this in any way. They are thugs. They are traitors. The whole world saw it. So did we.

The scene instantly evoked the meeting in the Berghof, and there is no reason to believe that their proud stupidity, vanity, and cruelty has a limit. They are not whatsoever constrained by considerations of decency, or the American interest. What we just saw is enough to know: Anything is possible.

The cowardice and dereliction of duty of the many, many Americans who have led us to this moment will never be forgiven. Every single worm responsible will live with the shame of this day—and this won’t be the last day we’re introduced to new depths of shame.

Destroying America is the only thing they will ever be known for, but they will be known for it for a very long time.

I have nothing else to say.

Schuschnigg wrote these notes immediately after the meeting. There is no way to confirm their accuracy.

I’m not sure Vance is a sidekick. He seems more like the ring leader/puppet master. Trump seems to me cognitively manipulated by whoever the last person he talks to. Macron and Starmer did a number on him to the point that he had genuinely forgotten he had called Zelensky a dictator. But this time vance got himself involved and took over the meeting and guided it to where he wanted to go. He’s not to me a syncophant or a sidekick anymore - he is the puppet master. I don’t think we are better off if trump goes and Vance is president. After yesterday I half expect Vance to article 25 the man himself at some point in the future. In so many frustrating ways Vance is the opposite type of VP that Harris was. And in so many ways exactly the VP that Harris needed to be - taking control in light of a cognitively dysfunctional president, and proving the ability to do the job And no, Starmer will not be able to manipulate vance the same way he was able to manipulate Trump. there is no manipulating Vance.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Godwin%27s_law

In 2023, Godwin published an opinion in The Washington Post stating "Yes, it's okay to compare Trump to Hitler. Don't let me stop you."[20] In the article, Godwin says "But when people draw parallels between Donald Trump’s 2024 candidacy and Hitler’s progression from fringe figure to Great Dictator, we aren’t joking. Those of us who hope to preserve our democratic institutions need to underscore the resemblance before we enter the twilight of American democracy."