Claire—here’s Arun’s primer on the French legislative elections, which might be useful to you if you’ve been following along with mine but want the story in a compact version. I’ve edited this to make it even more compact, but if you’d like to read the full-length version, you can find it on Arun with a View.

It’s my contention that none of this could make sense unless you know who these people are (hence my extended guide). But you’ve been reading my extended guide, so this should all make sense.

Arun Kapil

We are on the brink of a political earthquake the magnitude of which this country—ma deuxième patrie—has not seen in the adult lifetime of anyone reading this. By the July 14th fête nationale, Bastille Day, France may well have its first government of the extreme right in eighty years, and the first one ensuing from an election since the 1815 Bourbon Restoration. The earthquake will be felt across Europe—particularly in Brussels and Kyiv—and further afield.

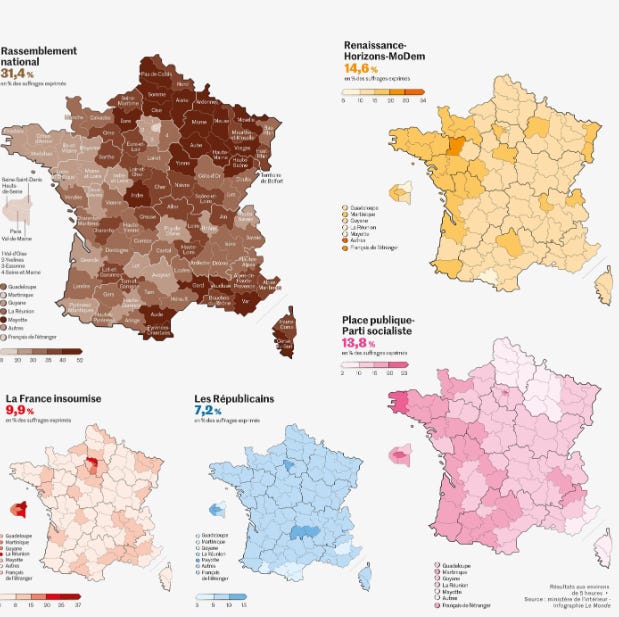

There was no big surprise in June 9 European Parliament election, no collective polling misfire. The extreme right-wing Rassemblement National finished way ahead, in first place, and for the first time in its 52-year history, broke 30 percent in a national election. Voter turnout (51.5 percent) was the highest it’s been in a European election since 1994. Pour mémoire, the RN was founded in 1972 as the Front National, changing its name (but little else) in 2018.

The Macronist center-right bloc, headed by the nondescript Valérie Hayer—entirely unknown to even politically informed persons before Emmanuel Macron picked her, three months before the vote—bit the dust. It finished below 15 percent (cf. 22 percent, in 2019), barely ahead of Raphael Glucksmann’s moderate-left, Parti Socialiste-dominated slate. The latter scored a solid third place, coming in four points ahead of Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise, whose slate, led by Manon Aubry, over-performed the polls and finished just shy of 10 percent. The strong performance of the moderates rectified the imbalance on the left of the past seven years, which saw the radical LFI establish itself as the dominant force thanks to Mélenchon’s strong showing in the 2017 and 2022 presidential elections, and the corresponding collapse of the PS in those contests. This imbalance in favor of LFI (of which more below) looks to be behind us, which is a good thing, for the left and for France.

There was much to analyze in the election results and many conclusions to be drawn, but hardly any time to do so on election night. Macron, one hour after the polls closed, threw a grenade (his own word, uttered privately) into the collective political class, announcing to the nation that in view of the election outcome, he was dissolving the National Assembly.

To say that his decision took everyone by surprise is putting it mildly. Over the subsequent days, two words were heard repeatedly from seasoned politicos and veteran political analysts and pundits, who’ve been around for a long time, seen it all, and know everyone who counts in the Paris political world: “sidération” (astonishment, stupefaction) and “inédit” (unprecedented).

Astonishment because absolutely no one—three or four of Macron’s advisers in the Élysée, plus Brigitte, excepted—saw it coming or had any idea that Macron, despite his unpredictability, was contemplating such a drastic move. Unprecedented, because while the President of the Republic has the constitutional authority to dissolve the National Assembly, never has a president of the Fifth Republic done such a thing under such circumstances. Elections to the lower house of parliament would now be held, with no forewarning, in three weeks. All 577 deputies would be elected in their single-member constituencies in two rounds. Absolutely no one was ready for it. What Macron has done is not only stunning and unprecedented: it is insane. Madness. And with potentially grave consequences: for France, Europe, Ukraine, and beyond.

Dissolving the National Assembly, bringing about early legislative elections, is one of the most consequential acts a President of the Republic can take. The constitution’s Article 12 does not oblige the president to provide a reason for such a decision. But some reasons are, politically speaking, considered valid, and will prompt the electorate to give the president a majority in the Assembly. Others are seen as not valid, causing voters to inflict defeat on the president’s camp.

A historical detour

To illustrate this point, consider the previous five times a President of the Republic has made use of Article 12.

October 1962: Charles de Gaulle, elected President of the Republic in 1958 by an electoral college of 81,764 mostly local elected representatives, enjoyed a majority in the National Assembly, with his Gaullist movement governing in a coalition with other conservative parties. De Gaulle wished to replace the electoral college with the direct election of the President by universal suffrage. This was certain to be rejected by the (indirectly-elected) Senate, whose assent was necessary to amend the constitution. De Gaulle thus took the decision—itself of dubious constitutionality—to invoke Article 11 of the constitution to organize a national referendum on the question.

The parties of the left, center, and non-Gaullist right vehemently opposed De Gaulle’s move. A censure motion was filed in the National Assembly. It passed, triggering the resignation of the government of De Gaulle’s newly-designated prime minister, Georges Pompidou. De Gaulle thus invoked Article 12, dissolved the National Assembly, and scheduled legislative elections. De Gaulle’s action was overwhelmingly viewed as valid—a legitimate use of Article 12—and the French people confirmed this later that month, giving him a landslide victory in the referendum and making his the dominant party in the National Assembly.

May 1968: A month of student demonstrations and union-led strikes had paralyzed the country. Striking workers then rejected an accord negotiated by Prime Minister Pompidou and union leaders. France appeared to be on the verge of insurrection. The 78-year-old President de Gaulle appeared clueless and unable to exercise authority. Revolution was in the air. But on May 30, de Gaulle went on the radio to specifically address conservative Frenchmen and women who were alarmed by the chaos. He announced that he was dissolving the National Assembly, which had been elected the previous year with a narrow right-wing majority. New elections would be held in 25 days.

De Gaulle’s wager paid off. The demos wound down and strikers drifted back to work. With order restored, attention shifted to the election campaign. When the dust settled, the Gaullist party had won a victory of historic proportions, achieving a majority in the National Assembly on its own (for the first and last time).

May 1981: François Mitterrand defeated Valéry Giscard d’Estaing in the second round of the presidential election on May 10, 1981, and the Socialist Party returned to power for the first time since the waning days of the Fourth Republic. Mitterrand’s first act as president was to dissolve the National Assembly, which had been elected in 1978 with a majority of the right, and schedule legislative elections two years early, on June 14 and 21. He hoped and expected voters would reaffirm the choice they had made in electing him and deliver a majority of the left. This they did, the Parti Socialiste and its allies winning a historic 37.5 percent of the vote (up from 25 percent in 1978), a feat it would never again achieve, and an outright majority of seats on its own, leaving it independent of the Communist Party. This was possible because France considers it legitimate for a newly-elected President to hold early legislative elections to achieve a governing majority. Without one, he can’t realize his agenda or make good on campaign promises.

May 1988: President Mitterrand was easily reelected for a second seven-year term. Logically, he dissolved the National Assembly that had been elected two years prior with a right-wing majority, ushering in the Fifth Republic’s first cohabitation. The broad left won a narrow majority in the June legislative elections, but the Socialists were some 15 deputies short. This left it dependent on the whims of the Communist Party—with which its relationship was difficult—to ward off censure motions and expedite legislation.

April 1997: Jacques Chirac, elected President of the Republic two years earlier, enjoyed a huge majority in the National Assembly, one made up of neo-Gaullists and myriad conservative and center-right formations who had been elected in a landslide in the 1993 legislative elections.

Looking ahead to the scheduled legislative elections in 1998, Chirac’s chief-of-staff, Dominique de Villepin, advised him to dissolve the National Assembly a year early. France was nearly in recession, with 12 percent unemployment. It would nonetheless have to implement austerity measures later that year to meet the European Union’s convergence criteria. This would provoke a popular backlash and cause the right to lose. Better, he reasoned, to hold the elections early and win with a smaller majority (the left was not viewed as a threat), then turn the austerity screws without having to worry about facing the voters for five years.

So Chirac solemnly announced to the nation that he was dissolving the National Assembly and elections would be held in five weeks. But his reasons for doing so were not entirely coherent (watch his ten minutes of word salad and charabia and try to make sense of it).1

It was clear to the informed public that Chirac’s action was driven by political calculation and he had no good reason to call the electorate back to the polls. The consequence: The left, which had looked to be out of the picture, used the three week window before the deadline to submit candidacies to forge an unexpected five-party electoral bloc—la Gauche plurielle—led by a resurgent Socialist Party and its uncontested leader, Lionel Jospin.

The Gauche plurielle, with minimal infighting and a plethora of strong personalities—a political A-list—took Chirac and the right by surprise, scoring a brilliant victory in the May 25-June 1 elections. Chirac’s politically-motivated invocation of Article 12 blew up in his face, consigning him to a five-year, mostly powerless cohabitation with Prime Minister Jospin.

The moral of the story: if you’re the President of the French Republic, don’t dissolve the National Assembly unless you have a reason that is considered valid by both the public and your political allies, particularly the incumbent deputies of your party or coalition, who will suddenly need to defend their seats in a reelection campaign.

If there were a compelling reason for Macron to decree a snap legislative contest on the evening of the European Parliament election, it did not occur to anyone outside his tiny circle of advisers. In his 9 pm address to the nation—which lasted not even five minutes, a record in brevity for France’s gasbag-in-chief, Macron observed that the result was “not good” for defenders of the European project, among them his “presidential majority.” He deplored the 40 percent of the vote that went to extreme-right parties, along with the “fever” and “disorder” that had gripped France. In view of the many “challenges” facing France, necessitating “clarity” in the public debate, he was thus invoking Article 12, with elections to be held in the minimum time period stipulated the constitution. (My loud reaction to his announcement was this).

A few points on Macron’s move. First, he has naturally been frustrated since the 2022 legislative elections, which unexpectedly failed to deliver a majority to his center-right electoral alliance, called Ensemble pour la République, spawning what was in effect a hung parliament. Macron’s prime minister, the haute fonctionnaire non-politician Elisabeth Borne—appointed in May 2022, after his reelection—was thus obliged to negotiate legislation with the fractious opposition, left and right, or invoke Article 49-3 and then ward off censure motions.

Borne competently executed Macron’s desiderata, demonstrating that he could in fact advance his agenda, albeit with a few compromises, and govern with a mere plurality in the National Assembly—though this did not stop him from unceremoniously, humiliatingly replacing her in January ’24, for no apparent reason, with the cherubic, germanopratin Gabriel Attal.

In fact, the hung parliament of the past two years transformed the National Assembly from the President of the Republic’s rubber stamp into a real parliamentary body—at least the way these work in most democracies. If Macron wanted an “indispensable clarification” from the electorate as to where it stands, he could have, at any point in his seven years in office, made good on his pledge to introduce a dose of proportional representation to the electoral system—or, better yet, entirely replace the single-member constituency two-round system with proportional representation, which would have axiomatically institutionalized multiparty coalition governments, but also dramatically increased the probability that Macron’s bloc would be an indispensable player no matter the outcome of a given election.

But since Macron manifestly prefers to have a rubber stamp, he could have at least waited for the debate over the budget in September or October, which, given the state of France’s public finances, promises (or promised) to be the Mother of all Budgetary Battles. The government would have inevitably invoked 49-3; this would have been followed by a censure motion from the opposition, causing the fall of Attal’s government. Macron, adopting the posture of Charles de Gaulle in 1962, could have then legitimately dissolved the National Assembly and allowed five weeks for new elections. It might not have given him an absolute majority but would have at least (somewhat) saved his legacy.

One is struck not only by the cynicism of Macron’s move, of its narcissistic, indeed solipsistic calculation, but also by how dangerous it is. And totally crazy. Macron’s gambit brings to mind that crackpot 2015 referendum in Greece, organized by Alexis Tsipras à la va vite. The date of the snap election meant that all candidacies would have to be filed with the relevant préfectures by June 16. So all the parties, caught utterly unawares, had exactly six days to come up with candidates and programs, print flyers and other media, raise money, mobilize activists, etcetera. Not to mention the organization of such an important election: tens of thousands of municipal employees suddenly had to be mobilized. All the voters leaving for vacation would suddenly had to apply for the vote par procuration, or vote by proxy (over 2 million so far).

And what kind of political debate could possibly happen in such a time frame? Given the stakes and configuration of forces in what is being called the most important French legislative election since at least the Second World War, Macron’s action is not only disruptive and dangerous, because it threatens to bring the extreme right to power, but an assault on democracy itself.

And to what end? One can only speculate, but it seems clear that Macron’s calculation centered on the left, whose historic division between la gauche reformiste (PS) and la gauche radicale (nowadays incarnated by LFI, with the PCF and ecologists straddling the two) has widened to a chasm since the collapse last fall of the NUPES—a shotgun electoral wedding of the left-wing parties—primarily, though not exclusively, over Israel-Gaza. The NUPES, initiated by Jean-Luc Mélenchon from a position of strength vis-à-vis the rest of the left, in view of their respective performances in the April 22 presidential first round, enabled the left to send 151 deputies to the National Assembly (half from LFI). Without the NUPES, the number of left-wing deputies would have been divided by at least two-thirds (with the PS all but wiped out).

Macron most certainly assumed that there was no way the left—where there’s a lot of bad blood among all sorts of people, and particularly around the polarizing figure of Mélenchon— would be able to come together in a NUPES-like alliance in less than a week, throw together some kind of electoral program, and, above all, decide which party gets what circonscription, or constituency, of which there are 577. So with several left candidacies in each circo, signifying that few would make the run-off, the stage woul be set for a second round of duels between Macron’s Ensemble and the RN. Left voters would yet again, one more time, vote for Macron (this time the macroniste) to block the extreme-right. Some who voted for the far-right in the low-stakes European election, always a vehicle for a protest vote or to send a message, would perhaps have second thoughts.

Macron, who thinks he’s brilliant, surely thought this strategy was equally so. Except that it wasn’t, as the PS, LFI, écolos, and PCF rose to the occasion and formed an electoral bloc—the New Popular Front (NFP)—that looks even more robust than the NUPES, despite the continued internal quarreling and backstabbing. The reason is so simple: unlike 2022, or any point in the past, the Front National—which is how the left still refers to that party—is on the threshold of power. A party whose Number 1 is named Le Pen could be in charge of the key ministries of government in less than one month. A 28-year-old named Jordan Bardella—who travelled in neo-fascist circles in his politically formative years and may be labelled, absent proof to the contrary, a closet neo-fascist himself—may well be prime minister of the French Republic come Bastille Day. While the National Front/National Rally is not a fascist party, it is, from the standpoint of French republican principles, beyond the pale. The dread, indeed terror, this sudden new reality arouses on the left—which, like everyone else, was blindsided by Macron’s move and what has ensued—is akin to that felt by US Democrats and anti-MAGA ex-Republicans at the specter of Trump winning the presidency in November while the GOP wins both houses of Congress.

A few comments on the left. First, on the reaction to the New Popular Front, the birth of which was quite remarkable in view of the open warfare that has broken out between the PS, PCF, and just about everyone else, on one side, and LFI, on the other, especially since several leading figures in LFI have themselves become dissidents against Mélenchon and his autocratic leadership. When the NUPES was born in May 2022, a not-insignificant number of Socialists refused to sign on to it, notably social-liberals (who would be establishment Democrats in the US) close to François Hollande and Manuel Valls (who led the right flank of the PS before quitting the party and becoming a rightist tout court). Their objections included the dominance of LFI (which was inevitable given the rapport de forces at that moment), LFI’s radical positions on issues across the board, its Euroscepticism, and the personality of Jean-Luc Mélenchon.

But the NUPES detractors are now on the New Popular Front bandwagon, among them former president Hollande (who is running for a seat in the legislature under the NPF banner) and Carole Delga, the leading Socialist Party personality in the southwest. When I heard that these two were on board—along with Raphaël Glucksmann, a target of LFI insults and invective during the European campaign—I knew the left would wage this campaign as united as it could possibly be.

That said, the Popular Front has in no way resolved the big problem on the left, which is the outsized weight of LFI and the even more outsized personality of Jean-Luc Mélenchon, which only aggravates the left’s electoral weakness. From the 1970s through the 2012 election, the national electoral strength of the left, as measured by the first-round vote totals of left presidential candidates, was in the 40-49 percent range. The threshold for winning a presidential election is about 43-44 percent. In 2017, a sizable portion of moderate Socialist Party voters defected to Emmanuel Macron when the leftist Benoît Hamon won their presidential primary. They stayed with him in 2022, causing a steep drop in the total stock of left votes to a mere third of the electorate. That is where the left vote has stubbornly remained. At a maximum, it is one-third of the electorate.

So the left—already fragmented and bitterly divided over identity-related issues that do not lend themselves to compromise—has no hope of returning to power. Moreover, polls over the past two years have consistently shown that when the parties of the left are polled separately, their total reaches 30-34 percent of voters. But when they’re polled as the NUPES or NFP, i.e. a single electoral bloc, the number drops three or four points, into the mid to high 20s.

The reason for the fall-off is not hard to divine: LFI and, above all, Jean-Luc Mélenchon are a repoussoir—a repellent—to a sizable number of moderate left voters, who are more than willing to vote for the Socialist Party or the ecologists but not the radical LFI (a US comparison would be Hillary Clinton voters who could possibly go along with Bernie Sanders but not with the leftist Bernie Bros, who hated her in turn).

The reformist left thus finds itself in a Catch-22. It’s unable to win, or even credibly contest, a national election under the prevailing electoral system without an alliance with the radical leftist LFI, but that very alliance causes voters to turn away.

Over the past two weeks, I have listened to two LFI-haters—one a friend, the other an Ensemble activist on the street—harshly criticize the PS for making a pact with the LFI devil rather than seeking an alliance with the centrists, specifically Macron’s party (or “party”), now called Renaissance (ex-République en Marche), and François Bayrou’s MoDem.

My response: (a) The idea of a center-left alliance is a nice one but could only be considered after a change in the mode de scrutin to proportional representation and away from the binary two-round system; (b) Renaissance is an empty shell; it is not a veritable party; without Macron it does not exist; so to negotiate an alliance with Renaissance is to do so with Macron, which is out of the question; (c) How on earth could such an alliance be negotiated and concluded in a week?; (d) LFI is not only Jean-Luc Mélenchon and his inner circle of acolytes and other grandes gueules on its margins, but also François Ruffin, Clementine Autain, and other worthy personalities with whom the reformist left can work; (e) Get rid of Macron first and then we’ll see.2

So for better or worse, and given that the hour is grave, for all those who are terrified by the specter of the RN in power—even if one doesn’t care about France, but does about Ukraine—there is no choice but to support the New Popular Front candidate, LFI or not, who is best placed to defeat the RN.3

Macron, the grenade he tossed having blown him up as well, has responded to the disaster he created by doubling down on his increasingly desperate attacks on the NFP and LFI, labeled “extreme left” and equated with the extreme right RN. And then there are the accusations of anti-Semitism—by Macron and all those in his camp, across the right, and into the left—against LFI in general and Jean-Luc Mélenchon in particular, which has hystericized the public debate, if people screaming at one another and engaging in ad hominem attacks can be called a “debate,” since last October 7.

One of the consequences of Macron’s action is to have, in effect, killed off his own political camp. Every last one of Macron’s allies, beginning with the members of his government and deputies of his “presidential majority,” feels betrayed by what he has done. They are all, to a man and woman, outraged, as, entre autres, most of them will find their political careers over by the evening of July 7. Emmanuel Macron has no political allies left. Not one. His face or name figures on not a single campaign flyer or poster of his “presidential majority.” The Gasbag-in-Chief has been blathering daily but no one is listening, and his erstwhile allies—macronistes whose political careers he launched—just wish he would STFU. What this will mean for the future of his presidency, whether he lasts to 2027, and France’s international position, we’ll soon have an idea.

Then there’s the Rassemblement National, on which I will say more next time (and times after that). Just one observation for now: not only did the RN cross the 30 percent threshold, it finished in first place in every part of the country save Paris and other large cities, with support from almost all demographic and occupational categories. Sociologically speaking, the RN electorate bears a strong resemblance to Trump’s in the US (rural and exurban, less educated), but it is now more representative of the French population than is any other party. The transformation of the RN’s fortunes, compared to seven years ago, when Macron entered office, is quite stunning.

The dikes are ceding. Voters no longer vote for the RN to send a message or cast a throwaway protest vote; a vote for the RN is now a vote of affirmation, an openly assumed expression of support by those who want the RN to come to power. And there is every reason to think—and fear—that it will.

Arun Kapil is a political scientist who lives in Paris.

Claire—recall that you can watch this with subtitles. YouTube’s procedure for making subtitles appear is absurdly convoluted, and having seen it stymie my ME101 students, I suspect a review is in order. By step:

Look at the lower right portion of the video, where among the icons you see is one that looks something like a gear. It’s to the right of the icon marked “CC.”

Click on the gear. A menu will pop up.

On the menu that just popped up, click on “Subtitles.”

You’ll be offered a series of choices. Here’s where people go wrong. Choose the language the video is in—in this case, French.

Now click on “Subtitles” again. This time, choose “Auto-translate.”

Pick “English” from the drop-down menu.

Why would YouTube make this process so complex? So utterly counterintuitive? I have no idea. But if you faithfully follow these instructions, it will work.

Claire—re. (a.): why? re. (b.): why again? re. (c.): the same way the New Popular Front came together (if they could do it, anyone could); re. (d.), I assure you that voters repulsed by Jean-Luc Melenchon will not be reassured by the argument that he comes with a Clémentine Autain bonus (and who are the other worthy personalities you have in mind—Manuel Bompard? Did you see what happened to the markets when they gave that idea a moment’s thought?); re. (e.), Macron is going nowhere and the election is tomorrow. A pity you and I didn’t hash this one out in time to save France.

Claire—And this will be better for Ukraine how, exactly?

Thanks to Claire for posting this succinct complement to her series on the French election. I found it entertaining, informative, and educational. It became educational because my French is so limited I had to go to an online dictionary five times to understand some of the phrases Mr. Kapil used. In so doing I ended up going down a couple of interesting rabbit holes (grandes gueles, germanopratin) that caused me to learn some new things. Time well spent.

I will have to fully read and digest all this but, have to say your writing and insights are just incredible. Wow!