Beyond Ripley

Adam Garfinkle explores the Age of Spectacle, artificial intelligence, and the politics of the unreal.

Claire—the essay below concludes The Age of Spectacle, a précis of a yet-unpublished book by Adam Garfinkle. Read the first three parts here:

Connecting the dots of American political dysfunction. A spectacle mentality has come to dominate our cognition and our political culture.

Spectacle defined and illustrated. It is associated with a distinct cognitive state. For many of us, this state has become our default setting.

The neuroscience of the Spectocracy. It has identifiable neurobiological correlates, and these are induced by our ubiquitous technology.

Beyond Ripley

The politics of the unreal

By Adam Garfinkle

Boost Phase Spectacle

Ripley’s Believe It or Not! now strikes us as quaint. These days, our affluence and technological prowess provide us with spectacles unimaginable at the dawn of the television age. The implications of this may be seen all around us, especially on the front page of the news.

The media’s treatment of Donald Trump’s latest indictment is an obvious example. The networks understand full well that they are Trump’s willing accomplices in the bid to dominate our attention. They understand, too, the damage this does to our civic health—or as Les Moonves infamously said, an all-Trump news diet “may not be good for America, but it’s damn good for CBS.” But business is business. If viewers want to watch the Trump Show all day long, the networks will cheerfully oblige. This unprecedented courtroom drama (to use the word they emphasize, over and over) is a hell of a spectacle. Last week the anchors could barely conceal their hope for an explosion of maddened violence outside the courthouse.

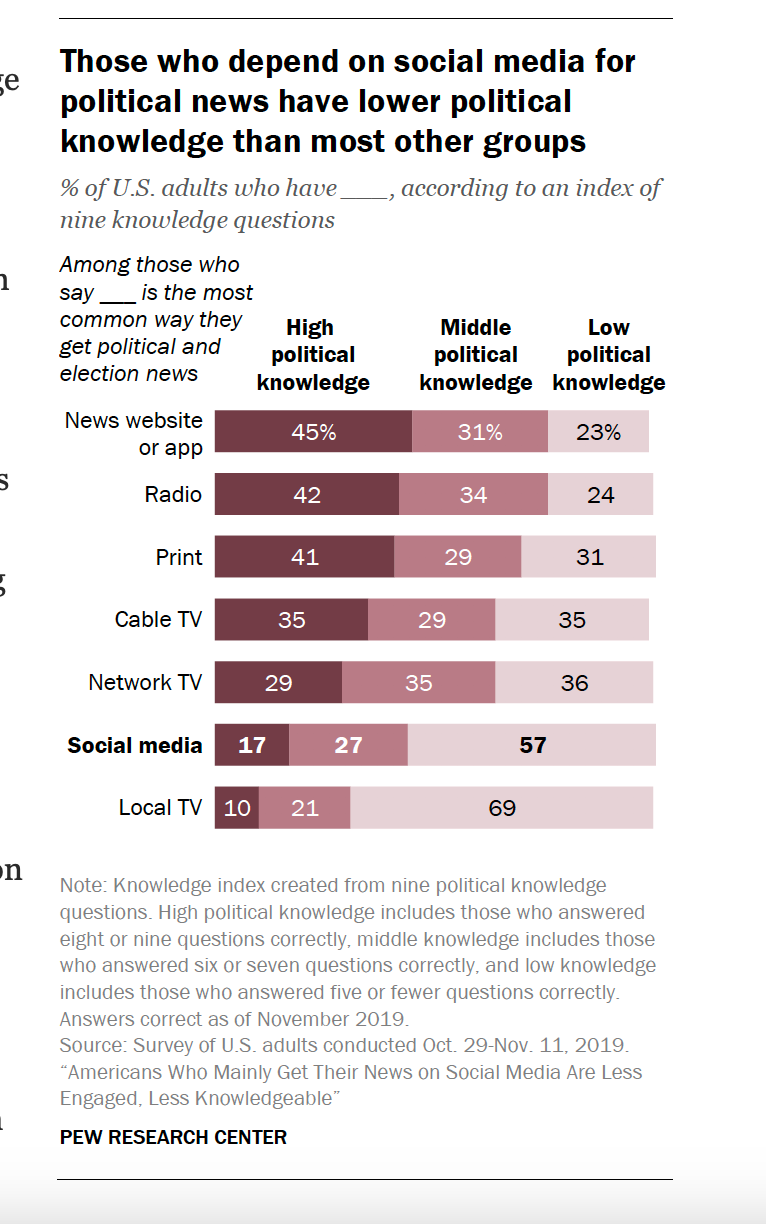

Most Americans do not read the news, they watch it—either on television or in video clips shared on social media. Numerous studies have shown that viewers of the news are less well-informed than readers. This is not only because video is an inherently emotional medium, not an analytic one, it’s because digital news has been steadily encroaching on television’s market share, especially among younger consumers, so the networks are now in a desperate race to the bottom for the attention of the elderly viewers who remain. This is why there’s no news on any of these shows. Had you relied on Fox or MSNBC to stay apprised of the news last week, you would have heard nothing about the stories in the most recent edition of Global Eyes. You would have heard nothing about any story, period, but Donald Trump’s indictment and arraignment.

The conflation of news and entertainment produces a spectacle, and spectacles induce a craving for more and bigger spectacles. This is the source of our political dysfunction. Yet we still fail to understand the dynamics of this process or the way the pursuit of the spectacular is shaping our society. Recently in The New York Times, for example, columnist Astead W. Herndon wondered how Trump’s legal travails would affect his political viability. Do his indictments, he asked, make him more or less fun? “The question is awkward,” he wrote,

as it suggests that the reasons some Americans are drawn to politicians are divorced from the seriousness of their office. But after Trump’s arraignment in federal court in Miami this week, I’m reminded of its importance.

There are, he concludes, “voters who are attracted to showmanship and celebrity.” These voters are otherwise “disengaged from politics,” but drawn to the Trump show because it entertains them:

What distinguishes this group? Perhaps you have a friend who doesn’t care about politics, but can’t believe Trump said THAT. Or who recognizes the belittling nicknames he bestowed on Republicans in the 2016 primary, like “Little Marco” Rubio and “Lyin’ Ted” Cruz, monikers that have stuck beyond Republican circles.

Herndon is almost there—he is aware that something very much like the two-headed carnival calf of old is playing a role our political culture—but he doesn’t appreciate that it is the dominant role. Nor does he understand its source: our new technology’s effects on our psychology and neurology.

Herndon cites a Democracy Fund study that found some five percent of Trump voters in 2016 might be classified as politically disengaged spectacle-seekers. But this is surely a grave underestimate. The better part of Trump’s base is there for the spectacle, and so are the better part of his detractors. The thrilling shows of humiliation and counter-humiliation recall pro-wrestling, and Trump understands this perfectly. This is why his campaign involves no serious policy proposals: There’s no need for them, and they would only ruin the buzz. This is why Trump threatens to pursue the “Biden crime family” and destroy “the Deep State.” It’s why he poses as a superhero: They are coming after you, but I am your protector.

It is also why his stunted vocabulary and his emotional affect evoke a B-list action movie. All the elements of a cheesy budget action flick are in evidence: low production values, a past-his-prime star, a familiar and formulaic plot. Our hero (or anti-hero) is in a dangerous or high-stakes situations: He has to save the world, seek revenge, and stop a criminal organization. Action sequences—fights, shootouts, explosions—keep the audience entertained. The characters and dialogue are simplistic. The focus is on the adrenaline-pumping action—there’s no complex storytelling, no deep character arcs. Movies like this aren’t meant to provoke thought: They exist to give viewers a fun and mindless escape. Everyone knows this, of course—except it seems that if you watch too many of them, you come to believe that this is the way the world really is, and wind up more comfortable in the imaginary world of a B-list action flick than you are in the real one.

Herndon doesn’t quite grasp this—the way entitlement, affluence, and marination in fantasy entertainment have turned politics, for far more than a small sliver of Trump’s base, into something like a violent video game: engrossing, but—and this is the point—not really all that serious.

In the 1970s, communications professor George Gerbner posited what he called mean world syndrome, a cognitive bias induced by violent content in the mass media. It caused viewers to see the world as more dangerous than it really is, he suggested, and this made them prone to chronic fear, anxiety, pessimism, and heightened vigilance. This is paired, in Trump’s base, with an assumption once confined to the 1960s counterculture: that the US government is the center of all evil in the country and the world. If it baffles you that Tucker Carlson has come to sound so much like Noam Chomsky, remember that Hollywood, not Poli Sci 201, is the viewers’ frame of reference, and in Hollywood, governments are not highly complex systems composed of real people in their infinite variety who are striving, mostly in good faith, to remediate problems that have no good solutions. They’re the Death Star. Once you accept this, then sure, why not: Donald Trump (of all people!) can play the crusading superhero.

For many who don’t read deeply—but also for many who do—a vivid procession of spectacles has overwhelmed reality and rendered ordinary life and its exigencies dull and flat. This has left them incapable of deciphering complex information, prone to magical thinking. Thus we see scenes like this:

A local mandate requiring masks to prevent the spread of Covid19 is a “Devil’s law” that will “kill people” and invite the wrath of God since it prevents one “breathing in oxygen,” Palm Beach County residents said. A wild public meeting was held on Tuesday in West Palm Beach, where county residents were invited to air their objections to a proposed law making face masks mandatory inside buildings and outdoors where it is impossible to socially distance.

The law eventually passed, angering some residents who shared their various conspiracy theories about a “communist dictatorship” that is “brainwashing” people about a “planned-demic.”

It’s easy to dismiss these people as bonkers, but there are so many of them, making such a wide variety of wildly irrational claims. Not since the early seventeenth century have so many Westerners inhabited a world like this, populated with village wizards and cunning men, astrology and prophecies, spells and witches. This can’t safely be ignored.

The phenomenon is not confined to Trump’s followers, nor even to the cognitively disadvantaged. The coders and titans of Silicon Valley are now racing to produce ever-more powerful artificial intelligence. In 2022, the Machine Intelligence Research Institute surveyed top researchers in the field: “What probability,” they asked, “do you put on human inability to control future advanced AI systems causing human extinction or similarly permanent and severe disempowerment of the human species?”

Nearly half the respondents thought the odds of this were at least ten percent—never mind more quotidian concerns that AI will automate away our jobs, flood our society with disinformation, complete our divorce from reality, inflame our political tensions, concentrate enormous power in the hands of unelected corporations, facilitate cyber attacks, usher in an era of total surveillance, lead to a dystopian arms race, and allow non-state actors cheaply to develop chemical and biological weapons.

Seized by the sense that this is all going too far, too fast, tech industry notables and prominent computer scientists—including the founders of the discipline—issued a plea to the tech giants. Please, just pause the riskiest and most resource-intensive AI experiments, they asked. For six months. In that six months, they proposed, the world could establish at least these minimal and rational protocols:

Mandate robust third-party auditing and certification.

Regulate access to computational power.

Establish capable AI agencies at the national level.

Establish liability for AI-caused harms.

Introduce measures to prevent and track AI model leaks.

Expand technical AI safety research funding.

Develop standards for identifying and managing AI-generated content and recommendations.

The petition made headlines, but had no effect. The experiments proceed at ramming speed. Why? Why would any sane person want to take such risks— particularly in the knowledge that if anything goes wrong, they will incur the world’s and history’s odium? (Should the world still exist.)

Let me propose an answer. The researchers and their bosses are addicted to spectacle. They just have to know what amazing and unexpected things the next generation of LLMs will do.

It may or may not be far-fetched to imagine advanced AI will threaten the human race. We just don’t know yet. That’s the point.

Cognitive illusions and magical thinking

We so much and so regularly enjoy entertainment made from anime and CGI—and now deep fakes, and soon, advanced AI-generated forms—that our habit of suspending critical thinking so better to immerse ourselves in these fantasy worlds has migrated, without our conscious awareness, to other domains.1

Technology enhances this effect. While smartphones instantly connect their users to a world of non-stop stimulation, it doesn’t connect users to the real world. It connects them to mediated images on a two-dimensional screen, leaving their brains to fill in the blanks, if they can. But they can’t—at least not well. The addictive user of digital devices thus develops a sense of reality poorly aligned with the real thing.

Most users, younger ones in particular, don’t even know how their phones work, so they experience an astounding complex every time they use them. “Any sufficiently advanced technology,” wrote Arthur C. Clarke, “is indistinguishable from magic.” Recall that magic means the laws of nature are inoperative. You feel the astonishment, you don’t think about it. Timelines melt so that there is no solid before and after. Magic is great fun, but it is not the proper cognitive basis for rational, purposeful behavior.

The more improbable the spectacle, the more we enjoy it. We desperately demand to be entertained, and our insistence upon turning everything into entertainment—the more spectacular the better—is now driving the bus.

Massive confusion about what, exactly, constitutes fake news is one consequence of this. Many are now cognitively stunted such that models of reality more complex than those depicted in adolescent fiction are literally unimaginable. They lack the ability to distinguish the factual from the fanciful. In trying to decide what to believe, they therefore privilege the source of a claim over its inherent plausibility or confirmability. Motivated reasoning becomes their only form of reasoning. Sources and audiences pair off accordingly, creating antithetical echo chambers. Each insists the other is watching fake news. The postmodernist claim that there are no objective facts and subjective feeling is all that matters becomes true, not because it is true, but because so many have lost or failed to acquire the skills required to disambiguate feeling from fact, fact from falsehood.

As with any drug, spectacle must be administered in ever-higher doses to provide the same pleaser kick. It must be ever-wilder, more implausible, more astounding. This may be achieved through technical innovation, more extreme content, or both. The manufacturing of spectacle—new and better video-games, better special effects, virtual-reality—is big business. Some of this is harmless entertainment for the younger set, like Pokemon Go. At least it gets the kids outside. But when the market for spectacle fuses with the market for outrage, it poisons our politics and inspires profoundly unhealthy discourse and behavior.2 It leads to QAnon and the storming of the Capitol—and much else.

Take Sandy Hook conspiracy theories.3 Adherents believe there was no massacre of little children. It was all a fake, staged by the government to advance schemes for gun control. These ideas are a spectacle archetype: They astound; they finger the government as the enemy; they invent fake facts and avoid or discount real ones; they are thickly discursive, for this better imitates the texture of reality; and they offer the frisson of uncertainty—believe it or not! But is now possible for the lowliest of entrepreneurs to create an astonishing simulacrum of a video that proves this—one in which the Feds, say, are viewed coaching the child actors, who after the sham massacre get up and dust themselves off, laughing and unharmed.

Those lost in the morass of QAnon believe firmly that somewhere there is a video showing Hillary Clinton and Huma Abedin chowing down on the face of a child. (They are said to have murdered the tot for a rejuvenating slurp of adrenochrome.) Think what this means: Large numbers of people have been moved to take political positions or even to storm the Capitol because of these beliefs. The addled Ashli Babbitt died trying to “save the children.” They believe this because of a video that does not even exist—but could all too easily exist. Then what?

A conspiracy theory is a protracted spectacle—an extended astounding complex brought under control for shared use. It is impossible to sustain the sensation of amazement a complex conspiracy affords on one’s own; it requires a group that takes turns amazing one another with new details, which is how a community of believers assembles around such a theory.

Like an optical illusion, a conspiracy theory is a cognitive illusion. The jolt of astonishment becomes special, rare, and guarded knowledge, known only to a handful of initiates. It is as if you are sucked into the screen, becoming part of the cast of an adventure show, seeing only what they see and doing the hair-raising things only they can do. But the script isn’t lighthearted Disney fare—it is political; to its adherents it is noble, to the rest of us, sinister. Behold the evil machinations of the Great Replacement! We must foil the enemy’s plot to destroy America as we know it! Some 80 percent of Americans now believe that the opposing political party, if not stopped, will “destroy America as we know it.” Of course they do. The story line demands it.

We are now crawling with odd political cults and groupuscules; these resemble the priesthoods of old. To be part of one is to feel special. There are rituals associated with membership, initiation criteria and rites. Sometimes one adopts a new name, an alias. Reality is so boring, and other people have jet-setter lives; you feel left out. You fix the envy by entering the cult. That is the interior cognitive design of QAnon, the Oath Keepers, the AR-15 Evangelical church congregations. As different as these groups are, they all use the same formula for producing and institutionalizing the wow-that-keeps-wowing.

In the world of the cult, like the world of the entertaining spectacle, the rules are not those of reality, defined as that which does not go away even when you stop believing in it. You die in a video game like Call of Duty, so you start a new game and you’re alive again. Then you can commit mass murder and not worry about getting arrested. Or you can find games in the superhero genre and go delightedly hunting down bad guys. The games don’t connect; linear time disappears; you can melt into your avatar so that it becomes just as real to you as your actual life, at least while you pay attention to it. You become immortal, or so it feels, but we are postmoderns, so feeling is all there is.

It is, all of it, advanced magical thinking. These Utopian delusions and conspiracy theories belong to the supposedly banished world of myth, where anything can turn into anything else—males into females and females into males and back again at will—and there is no before and no after. No constraints are imposed by physical reality and rare coincidences dependent on no known causal thread are the norm. The world of mythic consciousness comes back to waking life, hurtling forward on a cyber-highway of fantasy and spectacle. And now you see Donald Trump for what he is: a political shaman for those living in an ersatz world of the magical imagination.

How many forms can this condition take? Many, it seems. From sophisticated deepfakes to garden-variety political lies, political manipulations work best when delivered in the manner of our normal experience. But normal is now a world of the fantastic and the improbable. It is nasty to exploit this newly-childlike gullibility. One expects foreign intelligence services to pursue such opportunities. We don’t expect other Americans to do it—or at least, we didn’t before. In any event, we have given foreign and domestic cognitive swindlers a lot of help. We have constructed the scaffolding with our own credulousness.

Addiction to Spectacle: The Ultimate Danger?

Philip Rieff argued that our desacralized, secular world recycles storylines and images from mythic times as fiction, from Avatar to the zombie apocalypse.4 But as Rieff sensed, these aren’t necessarily understood as fiction by those with tenuous connections to the lebenswelt. In this new world, the foundational stories of Abrahamic religion have been demoted to fairy tales; the new gods erected in place of the God of Abraham resemble the old, bloodthirsty ones: They are embodied, capricious, and chimerical. In Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World, Tara Isabella Burton contemplates the weird cults, rituals, and subcultures that now flower in the place of traditional religion, from witchcraft and Paleolithic diets to Jordan Peterson fandom. Yearning for spirituality, the young are drawn from one god to another and one spectacle to the next. This, alas, is the spirit with which Silicon Valley is seized.

Ross Douthat wrote recently, and perceptively, that in the enthusiasm for AI,

we see attempts to link magic to science, or to deploy science to do magic, using telescopes or chemicals or vast computing powers to discover or create what the old magicians tried to conjure—namely, beings that can enlighten us, elevate us, serve us and usher in the Age of Aquarius, the Singularity or both.

His colleague Ezra Klein extended the metaphor:

this is an act of summoning. The coders casting these spells have no idea what will stumble through the portal. What is oddest, in my conversations with them, is that they speak of this freely. These are not naifs who believe their call can be heard only by angels. They believe they might summon demons. They are calling anyway.

This is escapism of the most dangerous kind, possibly the most dangerous in human history.

Hints of our condition—we are bored and we need a new spectacle—are everywhere. We see it in the lighter-than-air ideological mystifications of both the illiberal left and the illiberal right. Perhaps we’re in for an attempt to levitate the Pentagon from the left; and from the right, for those who thrill to hearing the sound of the shofar to signal the start of an insurrectionary attack, an attempt to collapse the walls of the Capitol.

These phenomena, though not of equal danger to life and limb, have one thing in common: a presentist’s obliviousness to limits. The spectacle hunter’s thought horizon resembles that of a child at play. He lacks any idea where his imagination might lead.

What happens when adults addicted to spectacle vanish into empowered children, besotted with myth and magic, lost in the narcissism of designer entertainment? Narcissus pined away while gazing at his own beauty. Will we meet a similar fate gazing at our beautiful machines?

Adam Garfinkle is a member of the Cosmopolitan Globalist editorial board.

See my “Disinformed,” Inference: An International Review of Science, 5:3 (Fall 2020), and more recently Tiffany Hsu, “As Deepfakes Flourish, Countries Struggle with Response,” New York Times, January 22, 2023, and especially Isaac Stanley-Becker and Naomi Nix, “Fake images of Trump arrest show ‘giant step’ for AI’s disruptive power,” Washington Post, March 22, 2023. As I and others predicted years ago, the deepfake problem is worsening and remedies remain elusive. China is experimenting with deepfakes as part of its propaganda and disinformation efforts in the first verified state use of GANs technology. See Adam Satariano and Paul Mozur, “The People Onscreen Are Fake. The Disinformation is Real,” New York Times, February 7, 2023. On the other hand, awareness of the problem is rising: Deepfakes played a cameo role, for example, in the recent “National Treasure” series.

See Richard Thompson Ford, “The Outrage-Industrial Complex,” The American Interest, December 18, 2019.

See Elizabeth Williamson, Sandy Hook: An American Tragedy and the Battle for Truth (Dutton, 2022).

Rieff, My Life among the Deathworks, Part One (University of Virginia Press, 2006).

Such a joy to read Adam's analyses as always. His critique is painstakingly apt. I am always marveling at the limitless post-truth person, tilting at every windmill hyperpartisan incapable of critical thought and self-reflection, who doesn't even believe merit exists, let alone parsing information on its merits. What worries me is that in a Kantian sense, this is an age bereft of objectivity and therefore lacking morality; and lacking independent judgment, we're incapable of moral judgment. We cease to be individuals. Now we're plastic automata, who, like cult followers believe, are the play-actors of transcendent spirituality. Which forecasts I think Ivan Karamazov's "everything is permitted." ""Let viper eat viper world." If there is no higher purpose for ourselves, and so none for politics, it explains how everything is a reductive, zero sum race to the bottom in every context. Net zero in the context of the climate apocalypse is magical thinking too. Not just Trump supporters or the progressive left are addled by conspiracy theories, but even educated people with political experience, like John Kerry and the self-important idiots at the World Economic Forum. Crisis and doom plague the 21st century. AI entrepreneurs are addicted to spectacle, but I think the scientists panicking about it too are addicted to spectacle in the sense of Net Zero people. Soon AI doom will be a business and there will be John Kerry's and Leonardo Dicaprio's going around and talking about how AI is going to kill all of us. From our social lives, to geopolitics, macro to micro, and back: the personal and the political have become so intertwined without principles, that we become susceptible to grand unificationist schemas that are life and death. Ironically it's awfully boring how excitable people are, which makes writing about it hard, because you feel like you're taking too seriously people who are idiots, and perhaps you feel like them, overreacting to something. If you worry about AI, you can be afraid you're indulging conspiracy theories. I'm a nervous person, and I get hung up that I'm hung about something if that makes sense, in my obsessive effort not to panic or believe in anything grand. Adam should do a supplementary post about how to deal with mass hysteria with awareness of the paradoxes in which the task of analysis subjects you.

Excellent analysis, and diagnosis. What's the prescription?