Balochistan: Asia's next headache

The last thing the world needs is a fierce new multinational battlefront on the borderlands of South and Central Asia. But it's getting one anyway.

Vivek Y. Kelkar, Mumbai

Few in the West could find the Pakistani province of Balochistan on a map. But a fierce new Asian conflict is gathering there, this time involving Pakistan, China, Afghanistan, Iran, and even India.

The Balochis are rebelling, violently, against the federal government in Islamabad, demanding independence or at least a measure of autonomy. They’re also furiously protesting China’s economic domination of their province.

China needs Balochistan. It’s crucial to Beijing’s Belt-and-Road Initiative. But insurgents have been killing Pakistan’s security forces in the region—and workers on projects managed by China—almost daily.

Balochistan shares long borders with both Afghanistan and Iran, and has ethnic and political links to both. Upheaval in Balochistan could send much of Asia into turmoil. It could engulf Pakistan in chaos, test China’s quest for geopolitical primacy, and stoke fires across Iran and Afghanistan.

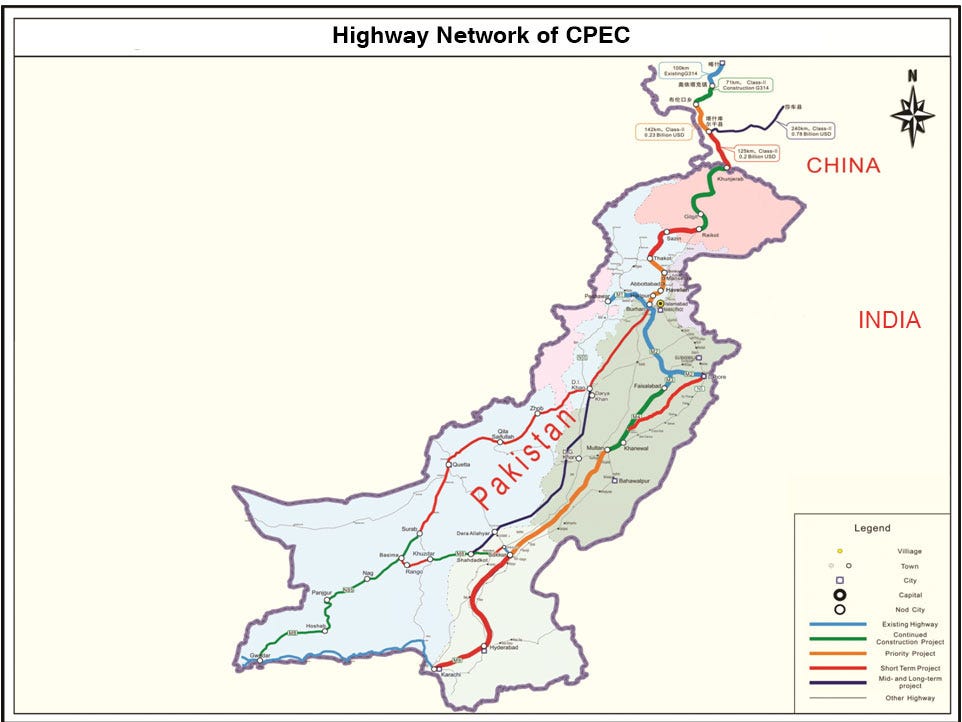

China controls the port city of Gwadar, which links Kashgar in China’s Xinjiang province to the Arabian Sea, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Persian Gulf. Part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, Gwadar is a vital route for the Belt-and-Road Initiative.

Balochistan province covers 44 percent of Pakistan’s landmass. It is crucial to its economy, with some of the world’s largest deposits of copper and gold, and Pakistan’s richest deposits of coal, oil, and natural gas. Recently, Pakistan’s state-owned petroleum company announced the discovery of massive gas deposits—one trillion cubic feet—in the province.

Recently, an editorial in Dawn, a leading Pakistani newspaper, described decades of “willful neglect” and “state machinations” that had left the people of the province “resigned to their fate.” But “there is a tipping point for everything. For people living in Gwadar, that moment has arrived.”

The proximate tipping point was a dispute over fishing licenses. More than a thousand Gwadar fishermen rose up against the issuing of licenses to Chinese trawlers for large-scale fishing off the Balochistan coast. Local fishermen cannot compete with the scale of Chinese mechanized fishing.

But the deeper reason was the decades-old dispute between the Balochis and Pakistan’s federal government.

A legacy of conflict

The Balochis have been fighting Pakistan’s federal government since 1947, when Pakistan secured its independence from Britain. Mir Ahmad Khan, the Khan (or ruler) of the princely state of Kalat, controlled the largest area of Balochistan. The British brought the Khanate under their control through the Government of India Act in 1937, claiming that Kalat was a vassal state, much against the objections of the Khan. There was considerable evidence that Queen Victoria had consented to Kalat’s independence in 1877.1 A legal battle followed.

The Khan’s lawyer was none other than Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the founder of Pakistan. When the British left in 1947, Mir Ahmad Khan declared Kalat independent; other Baloch tribes in areas directly controlled by the British Viceroy agreed that he was seeking independence on their behalf too. But in March 1948, Jinnah pressured the Khan to sign the Document of Accession. In April 1948, Pakistan’s army took control of the province.2

Since then, the Balochis have often resorted to violence in seeking more autonomy, and often independence, from Islamabad. Their leaders have protested the exploitation of the province’s natural resources. Pakistan’s federal government has ruthlessly suppressed these violent insurgencies, most notably in 1948, 1958-59, 1962-63, and 1973-77.

Relative calm prevailed throughout the 1980s and early 1990s. In 1998, the federal government tested Pakistan’s first nuclear device in Balochistan’s Chagai Hills, despite Balochi opposition. The disastrous radiation fallout persists to this day.

In 2001, under Chinese pressure, President Pervez Musharraf announced a multi-billion dollar project to develop the Gwadar port. Soon thereafter his government allotted concessions for vital copper and gold mines to China.

In 2006, openly backed by Musharraf, the Pakistani military assassinated a prominent Baloch leader, Nawab Akbar Bugti. Bugti, who had once been chief minister of Balochistan and a federal government minister, often protested that his province, which provided a quarter of the country’s natural gas, received barely five percent of the accrued revenues in return.3

In the late 1950s, according to a story that may be apocryphal, Bugti demanded a bigger share of the gas revenues. The rulers in Islamabad told him that natural resources belonged to God and the state.4 Bugti turned against the federal government, leading violent protests against the government’s policies on revenues, compensation, employment, and gas generation and distribution.

Even today, revenues generated by Balochistan’s mines and gas fields are at the core of the conflict. Balochi separatists contend that the Musharraf government gave prime infrastructure contracts to “outsiders” from Pakistan’s Punjab and Sindh provinces, especially at the Gwadar port. They allege that successive Pakistani governments have continued the discrimination.

An influx of workers from Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and—visibly—from China left locals jobless and incensed. Between 2011 and 2014, Islamabad enhanced the already strong military cantonments in the province at Khuzdar, Gwadar, Dera Bugti, and Kohlu. This fuelled even greater insecurity in the region and provided further impetus to the violent resistance.

Baloch national leaders viewed these gigantic projects with suspicion, seeing them as a ploy to settle Punjabis in Balochistan. The influx of Punjabi, Pashtun, Sindhi, and Chinese workers only increased their apprehension about the government’s real intentions. The Baloch people, who had already been under stress, began to see their interests as antithetical to those of China and the rest of Pakistan.

The federal government despatched former servicemen to tribal areas and sent more Pashtuns from the Northwest Frontier Province to Quetta. Wealthy Punjabis and army personnel bribed and then disinherited Baloch princes. Musharraf failed to devise a satisfactory scheme for allocating royalties. Baloch leaders viewed these developments with alarm, fearing they would lose their hold on the region.5

According to the Pakistani economist Qaiser Bengali, cited in Deutsche Welle, the Baloch people believe—correctly, in his view—that none of these agreements and Chinese projects have brought them anything. “China takes away 91 percent of revenue from the Gwadar port,” he said, while the rest goes to the federal government, and the locals in Gwadar don’t even have clean water to drink.

He also said that locals aren’t even allowed to enter the modern housing that’s recently been built in Gwadar. It’s all reserved for the Chinese. “Even elected members of the Balochistan assembly are not allowed to enter these facilities.”

The federal government continues to show its muscle. Balochistan is host to three nuclear testing facilities, six missile testing sites, six air force bases, and three naval bases, as well as 60 army precincts and four permanent army bases.

Over the decades, an assortment of militant groups such as the Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), the Baloch Republican Army (BRA), and the Baloch Liberation Front (BLF) has emerged. They are divided along tribal lines. Some demand Balochistan’s freedom. Others just ask that Pakistan’s federal government adhere to the many agreements it has signed over the years promising the province greater autonomy. All of them protest the exploitation of their natural resources, their ire increasingly directed toward the Chinese in the province and the security forces guarding the projects. The militants have frequently targeted gas pipelines, coal mines, and often, army security posts.

Radical Islamist groups, too, including the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan and the banned Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan, continue to operate in the region with impunity, demanding the imposition of the Sharia across the country. In the past, the Afghan Taliban, elements within the Pakistani armed forces, and the ISI (Pakistan’s intelligence service) have offered these groups tacit support. The TLP and TTP often target Chinese projects in Balochistan and the neighboring Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

China is worried

Pakistan and China cannot do without one another. The CPEC represents a potential US$65 billion investment in Pakistan—an investment even more critical with the country in an economic crisis. Nor can Pakistan do without China’s defense largesse. In early November, China gave Pakistan a Type 054 frigate, the first of a batch of four. The frigate, among the most advanced warships in the world, is based at Gwadar.

The Gwadar port is a vital ornament on China’s string of pearls—a series of ports, from Djibouti in the Horn of Africa to the Taiwan Strait, that will allow China to project power across the region. Gwadar is also China’s access point to the Persian Gulf, via a superhighway from Xinjiang through Kashmir and Pakistan, now under construction.

In August, suicide bombers struck a bus in Gwadar’s East Bay Expressway area killing two children and three Chinese workers. The BLA claimed responsibility for the attack. Chinese workers have been victims of targeted attacks in the neighboring province of Sindh, in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province abutting Afghanistan, and even in Karachi. In November 2018, Balochi rebels claiming allegiance to the BLA attacked the Chinese consulate in Karachi, killing four. During October of this year alone, the BLF led eleven attacks against Pakistan’s armed forces in the region, sometimes specifically targeting forces sent to secure Chinese projects. They often target migrant workers from other parts of the country.

In October and November, China and Pakistan’s federal government went on a massive PR offensive. Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan visited several parts of Balochistan and sought to assure the locals that they were the primary targets of the region’s economic development. Chinese media quoted the Chairman of the China Overseas Port Holding Company, Zhang Baozhong, saying, “According to our plan, Gwadar would become the logistic hub in this region within five years ... Gwadar will become one of the attractive cities in the world—a dreamland for human beings!” He claimed he had the support of all of Pakistan, including the local Balochi population.

But the ground reality remains different. Protests, marked by daily violence and killings, continue unabated. The protesting fishermen at Gwadar are threatening to bring work at the Gwadar port to a standstill. Efforts by Islamabad to bring some semblance of normalcy through elected provincial officials are met with skepticism, and these officials are often the focus of militant attacks.

Last week, following months of pressure from Beijing, Imran Khan reached a peace deal with the TLP and a month-long ceasefire agreement with the TTP. But China fears the Afghan Taliban and right-wing elements within Pakistan’s military and the ISI remain sympathetic to these extremist organizations. The many militant groups in Balochistan, and indeed across Pakistan, see the government’s deals as a sign of weakness.

Though Islamabad has been threatening to go all out against these groups, it would have great difficulty carrying out major military operations, like those it conducted in 2015-16, without American help. The US supported the Pakistani army’s actions across Balochistan, Waziristan, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa with drones and satellite imagery. China, fearing backlash from Muslims in Xinjiang, may not be quite as willing to use its military resources to target Islamic groups such as the TTL and TTP.

The Afghan Needle

The Taliban in Afghanistan are still trying to come to grips with running the country, especially the volatile tribal areas. The Afghan Taliban continues to face the threat of revolt within its ranks and opposition from groups such as the TTP, which has long had bases in Afghanistan. This leaves China worried. It has much to gain through Afghanistan for the BRI, and much to lose if these groups gain purchase there.

Balochistan’s provincial capital Quetta is home to the Quetta Shura Council, a body of powerful Afghan Taliban leaders formed in May 2002. The Quetta Shura was instrumental in the Taliban retaking Afghanistan. Known al Qaeda elements operate out of the city and their links across the region are extensive. Quetta has a significant Pashtun population.

Balochi separatists and opposition leaders have sought, and found, a refuge in Afghanistan at least since the 1970s. Reports indicate that the Afghan Taliban is now trying to persuade the Balochi separatists to find new hideouts in neighboring Iran, whose Sistan province shares both a border and ethnic ties to Balochistan. Interestingly, the British divided Balochistan between Iran and the Indian sub-continent in the late 19th century. Sistan province, with its Balochi ethnicity, went to Iran. The Balochis are Sunnis. Iran has a Shia majority. Sistan is a trouble spot for the Iranian government in Tehran.

Odds are the Afghan Taliban will succeed in persuading the Balochi separatist groups to move to Iran, though Tehran will not be exactly welcoming. But it is doubtful the Taliban will meet Islamabad’s and Beijing’s demands to flush out the TTP and Uighur militant groups, such as the East Turkestan Islamic Movement in Afghanistan. These attempts are unlikely to succeed because of the underlying al Qaeda links.

ETIM has been operating in Afghanistan’s Badakhshan province, next door to China’s Xinjiang, since the American withdrawal in August. The Afghan Taliban is trying to persuade ETIM to move to other parts of Afghanistan and has begun attempts to broker peace between the TTP and Pakistan.

The Indian angle

Any problems in South Asia perforce involve India. Delhi officially denies interfering in Balochistan. But Islamabad blames India for every violent incident. It has sought to portray India, both at the UN and other forums, as the mastermind behind the unrest in Balochistan, arguing that locals would have little incentive to pursue violent ends without Delhi’s support.

Despite India’s official claims to the contrary, Balochi opposition leaders have received medical treatment in India in recent years. Some allege that Delhi has long supported Brahamdagh Bugti, grandson of the slain Nawab Akbar Bugti and a leader of the Baloch Republican Party.

Bugti, now exiled in Switzerland, denies India’s support, but openly demands support from Iran. Bugti’s BRP is allied to the militant Baloch Republican Army that comprises his clansmen.

But another BRP leader in exile in the US, Dr. Walid Baloch, told Dawn in 2010,

We love our Indian friends and want them to help and rescue us from tyranny and oppression. India is the only country that has shown concern over the Baloch plight. We want India to take Balochistan’s issue to every international forum, the same way Pakistan has done to raise the so-called Kashmiri issue. We want India to openly support our just cause and provide us with all moral, financial, military, and diplomatic support.

A Pakistan consumed by insurgency in Balochistan and other provinces is undeniably preferable to India. It relieves pressure from its problems in the Kashmir valley.

Balochistan is vital to Pakistan’s economy. In 1947, Mir Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo, a Baloch nationalist, emphasized the importance of the province to Pakistan’s economy. “Pakistani officials,” he said, “are pressuring [us] to join Pakistan because Balochistan would not be able to sustain itself economically [but] we have minerals, we have petroleum and ports. The question is where would Pakistan be without us?” A Pakistan with limited access to Balochistan’s natural resources would be an even worse economic basket case than it is now, at least in Indian eyes.

China’s control of Gwadar port grants it unfettered access to the Arabian Sea and the Persian Gulf. Unrest at Gwadar port helps India by threatening China’s control of the region and leaving the Indian navy slightly less vulnerable.

The unrest is causing investors to hedge their bets. In June, Saudi Arabia decided to shift a US$10-billion oil refinery project from Gwadar to Karachi.

China might be playing things cautiously too, though its media machinery takes pains to stress that it’s not. In September, Pakistan and China announced a US$3.5 billion project to overhaul the port at Karachi with a mixed-use project that would include residential, commercial, and seaport zones. Islamabad and Beijing took pains to emphasize that this was a direct investment by China, not a loan to debt-strapped Pakistan. Chinese media also emphasized that the project was not a shift away from the Gwadar port, as many in Balochistan feared.

Two weeks ago, Pakistan’s government sought Beijing’s intervention when the China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation—Sinosure—delayed the underwriting of US$13 billion in insurance for several energy and infrastructure projects and the US$8 billion rail link between Karachi and Peshawar. The unrest in the region, leading to long delays in project execution, had caused Sinosure to hesitate and delay.

Balochistan is a festering crisis—a looming disaster for Pakistan, a test for China, a nuisance for Iran, trouble for Afghanistan, and an opportunity for India. But another battlefront on the borderlands of South and Central Asia, and indeed Iran, is something the world could do without.

Francesca Marino, Balochistan: Bruised, Battered, and Bloodied (Bloomsbury: November 28, 2020).

Mahrukh Khan, “Balochistan,” Strategic Studies 32 (2012): 200-223.

See Javeria Jahangir, “Political Culture of Balochistan during Military Regime of General Pervez Musharraf and Indian Interest in Balochistan,” Journal of Indian Studies Vol. 6, No. 1, January – June, 2020, pp. 83– 118.

Ibid.

I am indebted to Javeria Jahangir, op. cit., for his elucidation of these points.

"Few in the West could find the Pakistani province of Balochistan on a map." Come on, man! That's what Google is for. I've never heard of it, and when I first saw the headline I thought "What is balochristian? Something to do with Charlemagne? :-)

Another brilliant and informative essay from Mr. Kelkar just as we’ve come to expect from him. But I do have one question. He says,

“But another battlefront on the borderlands of South and Central Asia, and indeed Iran, is something the world could do without.”

I might be missing something, but isn’t this an imbroglio that we should be celebrating if not joining India in doing what we can to exacerbate?

How many geopolitical hotspots offer a confluence of events that allow the West to stick it to two of our biggest adversaries (China and Iran) at such low cost?

A destabilized Iran in particular is in American interests. Hopefully we are covertly supplying whatever aid and support we can provide to both Pakistan’s and Iran’s Baluch separatists just as we are hopefully supporting the Separatist aspirations of Iran’s Azerbaijani population which were surely reenergized by Azerbaijan’s defeat of Armenia.

As for China, aren’t they merely imperialists in exactly the same way that Britain, Russia and the Ottomans once were?

Instability in Baluchistan seems like great news; no? Why is this a conflict that Mr. Kelkar would be better off without?