Are we headed for war in the Pacific?

The great powers are playing a high-risk shadow game. But such games have a nasty way of coming out of the shadows—with terrible consequences.

Vivek Y. Kelkar, Mumbai

On September 23, Taiwan formally submitted its application to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership. On October 1, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force began its incursions into Taiwan’s air defense identification zone. Over the course of four days, 148 aircraft—including nuclear-capable bombers, anti-submarine aircraft and airborne early warning and control plane—flew into the zone. A record.

On all sides, the warlike posturing has been intensifying. Throughout the month of August, the United States led six allied nations in one of the biggest naval exercises in the western Pacific in decades. In mid-September, the United States, Britain, and Australia announced a security pact to share cutting-edge defense technologies and equip Australia with nuclear-powered submarines. The US considered this deal so imperative that it gladly paid the price of offending France, whose own submarine deal with Australia was unceremoniously deep-sixed.

The PLA has been posting minatory videos: Set to thumping soundtracks, they depict amphibious assaults on places that resemble Taiwan.

One showed a simulation of the bombing of Andersen Air Force Base in Guam:

Last week, the CIA announced the formation of a new unit, a dedicated China Mission Center. On the same day, The Wall Street Journal revealed that US troops had been deployed in Taiwan for “at least a year.” The leak appeared to be strategic. The Biden Administration, presumably, wished this to be known. Hu Xijin, the editor-in-chief of China’s party mouthpiece, the Global Times, frothed at the mouth: “See whether the PLA will launch a targeted air strike to eliminate those US invaders!” On October 11, China’s military announced that it had carried out amphibious assault drills in Fujian province, directly across the sea from Taiwan.

Where is all of this heading?

The shadow game

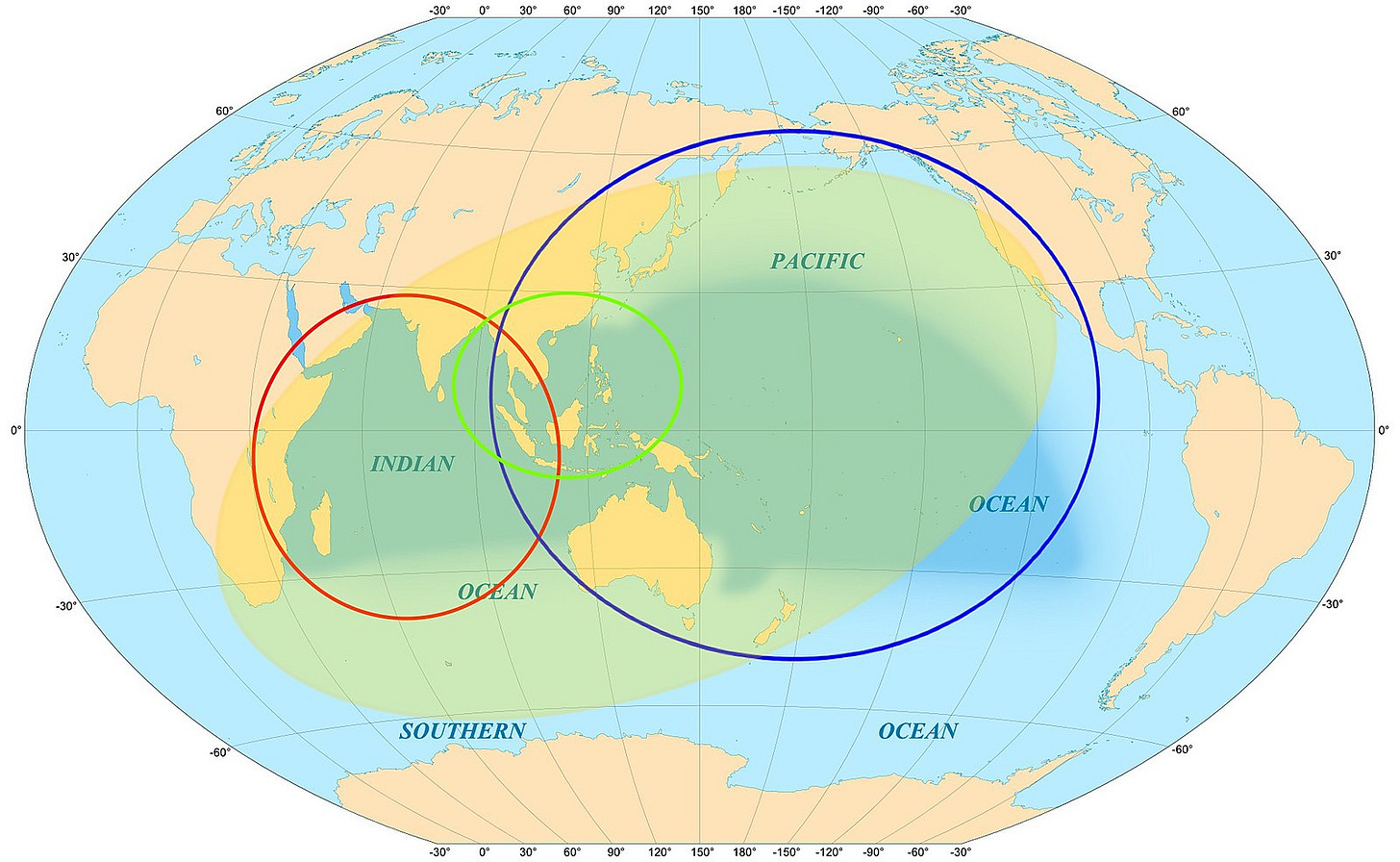

A shadow game among the world’s great powers is playing out across the Indo-Pacific. The region spans nearly half the globe—from Korea to Australia and the Indian subcontinent—and is inarguably the world’s economic powerhouse. All of the players have a major stake in the outcome. But if the stakes are high, so are the risks. The world’s perception of China—and its own perception of itself—will play a key role in this game’s denouement.

Mainland China and the ruling Communist Party (the CPC) seek to reintegrate what it terms the “renegade province.” But in the CPC’s view, this is no mere matter of tying up loose historical ends. China aspires to assert itself as the region’s hegemon. Imposing its will upon Taiwan would mark its success, both domestically and abroad.

In turn, South Korea, Japan, Australia, and the littoral countries of the South China Sea are not worried solely about the disruption of traditional regional power equations. They fear that China, with its inflexible political system and radically different understanding of fundamental freedoms, will come not only to dominate the region economically, but impose its will upon them politically.

India fears a military confrontation with China and the destabilization of an already turbulent subcontinent. China’s recent incursions into India’s Ladakh region were not just displays of military muscle, but creeping invasions, aimed at seizing territory. Since devouring Tibet in 1952, China has claimed India’s easternmost region, Arunachal Pradesh, as “Southern Tibet.” A weakened India means even more power for China, across a far wider swathe of the globe.

China’s aggressive military maneuvers in August and September 2021 in the Taiwan Straits surprised many headline-writers, but they shouldn’t have. This shadow game has been building in intensity for several years—certainly since December 2, 2016, when Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen spoke directly to President-elect Donald Trump. The Trump Administration said they had discussed “close economic, political and security ties.” More significant than the topic of discussion was the fact of it. US and Taiwanese heads of state had not spoken directly since 1979, when the US broke ties with Taipei in a bid for rapprochement with Beijing.

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi dismissively termed the call a “petty trick,” but there was nothing petty about the trade wars that followed. These were the opening salvos in the contest for Pacific hegemony. Economic wars are, after all, wars: They are meant to weaken one’s rivals.

Significant, too, was the change in American language issuing first from Trump’s secretary of state, Mike Pompeo, then from his successor, Antony Blinken. In November 2020, during a radio interview, Pompeo said,

Taiwan has not been a part of China. That was recognized with the work that the Reagan administration did to lay out the policies that the United States has adhered to now for three-and-a-half decades.

On January 9, 2021, Pompeo announced the removal of restrictions the State Department had imposed upon itself. These included a prohibition on referring to Taiwan as “a country” or “a government.” In Pompeo’s words, the Department had imposed these rules “unilaterally, in an attempt to appease the Communist regime in Beijing.”

“No more,” Pompeo wrote.

In June this year, the Biden administrations reimposed some restrictions. But on September 19, testifying before Congress, Blinken referred to Taiwan as “a country,” and it wasn’t the first time. On March 10, at the tail end of a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing, a representative called upon the administration to begin talks with Taiwan on a free trade agreement. Blinken responded that he was “absolutely committed” to doing so, describing Taiwan as “a country that can contribute to the world, not just its own people.”

The change in nomenclature surely alarmed Beijing, as would the idea of deeper trade ties between Taipei and the US—particularly in the telecom, semiconductor and artificial intelligence sectors, where China seeks the global lead.

On September 11, the Financial Times reported the Biden Administration was “seriously considering” granting Taiwan’s request to change the name of its representative office in Washington from the “Taipei Economic and Cultural Representative Office,” which Beijing finds palatable, to the “Taiwan Representative Office,” which it does not.

On October 7, the Wall Street Journal broke the story that US special forces had been training their counterparts in Taiwan for more than a year. Surely this did not come as news to China. But the reporting of the story is what matters to Beijing.

Perception matters most

Beijing’s ruling elite is acutely sensitive to the way it is perceived. It would not casually dismiss Pompeo’s actions or Blinken’s words as functions of American domestic politics, or characteristic American verbal carelessness. Nor would it dismiss the leaks about US forces in Taiwan as mere hubbub in the media. From Beijing’s point of view, such reports disrupt the world’s perception of its relationship with Taipei, calling into question China’s ability to achieve complete economic and political dominance in the region. Beijing finds this kind of symbolism immensely significant.

China would be acutely aware, too, of the perceptions generated by the announcement of the trilateral AUKUS deal. It’s not just that Canberra will acquire nuclear submarines. The three countries will develop joint capabilities in undersea, artificial intelligence, and quantum computing technology—clear advantages in a global cyber war game. Beijing sees the move, correctly, as an American effort to develop a new naval counterweight against its growing power, one that could develop into a full-fledged military alliance, undermining China’s ambitions to assert military and cyber control over the Pacific.

Weighing heavily on the mind of China’s elites, too, is the fate of the Chinese property developer Evergrande and its enormous mountain of debt. The Evergrande crisis, China’s crackdown on overly-independent tycoons, and the global media’s speculation about the impact of both on China’s economy all play into Beijing’s decision-making. China’s aggressive flights, which began in late August, should have come as no surprise: In Beijing’s calculus, baleful perceptions must be countered.

Note, however, that Beijing played its hand carefully. Chinese aircraft flew into the air defense identification zone around Taiwan—the region in which Taiwan reserves the right to demand that foreign aircraft identify themselves—but cautiously avoided flying directly into sovereign Taiwanese airspace.

The internal dimensions

China’s economy is now poised at a critical threshold. The way General Secretary Xi Jinping copes with this challenge will determine not only his future, but that of the Party.

China does not yet possess the globally dominant economy to which it aspires, nor will it ever escape the limitations inherent to its economic model. In 2019, according to IMF data, China’s gross national savings—including both household and corporate savings—amounted to 44 percent of its GDP. This seems healthy at first glance, but it suggests something puzzling: China’s net but fixed investment is about 43 percent of GDP. Concurrently, GDP growth levels have been falling in recent years, with export levels tapering off from their pre-2008 highs.

So where has the money from these massive savings gone? They’ve chiefly gone into property and real estate, creating an unsustainable bubble. Real estate in cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen has become some of the most expensive in the world, while rates of home ownership have reached 93 percent. Housing wealth accounted for 78 percent of all Chinese assets in 2017. Along with China’s urbanization—60 percent of its population now lives in urban centers—and the rapid greying of its population, this means the property boom is at its end.

Even more indicative of crisis, Chinese household sector debts are now 61 percent of GDP, while those of the non-financial corporate sector are a whopping 159 percent. Economists Kenneth Rogoff and Yuanchen Yang have pointed out that the property and real estate sector contributes to 29 percent of China’s GDP. It all adds up to a bubble that’s been waiting to burst.

Apart from this, Beijing’s ruling elite fears, above all, social tensions arising from income disparity. The World Bank estimates that China’s Gini coefficient—an economic measure that indicates levels of income inequality—puts China among the most unequal countries in the world, even more so than the US. This is what triggered Xi Jinping’s recent rhetoric about “common prosperity.”

But whether the “common prosperity” plan will succeed in reducing income disparity is far from clear. There is no way to prevent further deterioration in the property sector. The implications are far-reaching. Rogoff and Yang estimate that a 20 percent fall in real estate activity could cause a 5-10 fall in GDP, “even without amplification from a banking crisis, or accounting for the importance of real estate as collateral.”

It’s unclear what path the government will now take to move spending towards consumption and away from investment in real estate, or how income can be redistributed toward households, especially in the poorer sections of the country. Beijing has sold its crackdown on China’s technology tycoons, which began with its repression of Jack Ma last year, as a step on the path toward “common prosperity” and away from “disorderly corporate expansion.” But among global investors and local entrepreneurs, these measures can only raise the kind of doubt that does not augur well for China. Following the crackdown in Hong Kong, nations—and capital—across the region and the wider world have come to the realization that China is an authoritarian power, and it has no intention of changing.

The Xi-factor

For Xi, these economic challenges could not come at a more sensitive time. In 2022, Xi is up for reelection to yet another five-year term as China’s supremo. He has eliminated regulations that stand in his his path, like two-term limits. He has a considerable power base within the party. He has marginalized Prime Minister Li Keqiang. He chairs key committees that drive China’s foreign and economic policy, as well as the Central National Security Commission, which not only influences economic policy, but effectively controls the country’s internal security. But worsening economic conditions could set off whispers among his detractors.

This means a great deal rides on the way the CPC perceives his actions—and whether rival, marginalized power factions are willing quietly to go along with him. It is no coincidence that Xi’s political deadlines are concurrent with his term in power. He has signaled that China’s target is complete military parity with the US by 2027. The state-run Xinhua agency recently reported that Xi asked his generals to establish a new system of military training, one that would accelerate the transformation of the PLA into a world-class force, again with the target date of 2027.

Taiwan has signaled its worries about this deadline: Defense Minister Chiu Kuo-cheng recently said China would have the ability to mount a full-scale invasion by 2025. Taipei is on a massive arms-buying spree. Even though it knows it cannot compete militarily, it seeks to make the cost of an invasion as high as possible. By roping the UK and Australia into the military dynamics of the region and building closer ties with Japan and India through the Quad, the US is keeping its irons in the fire—even if its appetite for military excursions abroad has diminished considerably.

So is there war in the offing in the Indo-Pacific? Not immediately, perhaps, but in the long term, it is certainly possible. For China and the US, and indeed for wider region, the stakes in this shadow game across the South China Sea and the Indian subcontinent are massive. Shadow games have a nasty way of spilling into the real world, with terrible consequences. That’s why the beliefs and perceptions created by each player’s moves and counter-moves are crucial.

Even if the US has little appetite for another war, the world has—if only gradually—shown itself willing to stand up to China’s belligerent wolf-warrior diplomacy. Despite China’s military and economic strength, this kind of resistance could prove hugely disruptive to Xi’s plans. In recent years, for example, South Korea refused to bow down to China’s threats of economic retaliation for its purchase of a US missile-defense system. China’s sanctions on Australian exports—a punishment for asking impertinent questions about the origins of the pandemic—pushed Canberra right into the arms of AUKUS. Even little Lithuania, infuriated by Beijing’s bullying, set up an embassy in Taiwan.

For Xi and China, the game could not be riskier. It’s a standard move in the dictator’s playbook to use war to distract from domestic economic problems and forestall social unrest. What’s more, Xi may want to leave office on a high, as the man who “unified” China. But realistically, what are his options?

First, he could tell the PLA to march across the Strait into Taiwan immediately, in the assumption that the US retreat from Afghanistan signals its decline and unwillingness to fight faraway wars.

Second, he could wait for a moment of US distraction or a definitive sign the US has concluded Taiwan is not worth defending militarily.

Third, he could wait until the PLA believes they have the measure of the US military-which he has ordered it to gain, and gain swiftly.

China’s carefully calibrated incursions into Taiwan’s ADIZ may have been purely symbolic, or they may have been designed to test global reaction. It is possible that a range of Western signals—the AUKUS deal, US officials’ resolute rhetoric in the Senate and the House, US and allied troop movements in the South China Sea, the acknowledgement that US Marines are indeed training Taiwanese troops—caused Xi to blink before deciding this was the moment for an invasion. Xi’s reiteration, last week, that China would seek the integration of Taiwan by “peaceful means” might suggest so.

Xi and senior CPC leaders could not have failed to notice that global sentiment toward China is not warm, particularly in the wake of the Covid19 pandemic, China’s diplomatic and trade belligerence, and its ham-fisted crackdown on its tycoons. And while Xi’s position in China looks unassailable now, we don’t know who is whispering, or what they are saying, in hidden quarters of Beijing.

In the event of war, Beijing cannot count automatically on Russia as an ally. Putin will put his interests in Eastern Europe first. He may not want to take on the West so directly—not, at least, until he is reasonably sure his interests there are secure from a militarily challenge.

From Xi’s perspective, options two and three are for now the best choices, the more so because the US has of late signalled unwillingness to abandon Taiwan, grasping its significance in the region as a wedge against China.

But war often happens by accident. It is hard to predict how a dictator will think in a crisis. It is also hard to predict how duly-elected officials will think. So this is a genuinely perilous situation. A Pacific war, sparked by Taiwan, would be a bloody cataclysm, and no one would be well served by it. That does not mean it cannot happen.

typo: "his his path, " Good article. Not enough attention paid to the Climate Crisis effect and the Covid Effect and the ramifications world wide.

The site looks great and it is rocket fast, BTW.

Another point to be noted is the the appearance on the American Left of an anti-anti-China movement. Essentially this is an alliance between progressive antiwar groups and progressive Asian-American advocacy groups. Their claim: that a robust US response to the Chinese threat stokes racism and incites hate crimes against Asians. Needless to say, that all-purpose demon, “white supremacy,” lies at the root of the problem.

Whether these activists are acting in good faith or not I leave for others to decide, but there can be no doubt that their campaign is very serviceable to the Chinese regime. For instance they condemn negative characterizations of the regime as inherently racist. Also they argue that the security threat posed by China is greatly exaggerated. All this must be music to the ears of of the Chinese oligarchy.

This wouldn’t matter very much if it was a phenomenon confined to the deep reaches of the progressive fever swamp. But it has already gained a foothold in the Democratic Party, where the likes of AOC and Bernie Sanders embrace the position of the anti-anti-China movement in whole or in part.