Summary:

Elected officials should be held to a “reasonable elected official” standard analogous to the reasonable person standard. If they fail to behave with the same degree of care, knowledge, experience, fair-mindedness, and awareness as a hypothetical “reasonable elected official,” voters should relieve them of their responsibilities at the first available occasion.

Resolved: This newsletter holds that the Trump Administration did not meet this standard.

A debate

One of my readers—Lieutenant Colonel Adam Tharp—believes my judgment of the Trump Administration’s handling of the pandemic too severe. I don’t yet know why, but I’m intrigued to know what it might be: His professional experience is such that if anyone could muster an informed counter-argument, it should be him:

Adam C. Tharp served as a United States Marine for 27 years and participated in combat and contingency operations in the Balkans, East Africa, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Southeast Asia. He’s spent the last five years as an operational planner for US military engagements in Europe, Africa, and South America. He is a graduate of the US Army School of Advanced Military Studies and holds Masters in Public and Business Administration.

So I suggested we stop bickering on Twitter and have a proper debate. He has graciously agreed. In the next newsletter, I’ll publish his case against the resolution.

While the proposition is a narrow one, the argument I make has wide applicability. It was not just the Trump Administration that failed. Local and state officials throughout the Western world failed to meet the “reasonable elected official” test. They should be ejected at the first available occasion.

It is often said that the great virtue of democracy as a form of governance is that citizens may hold elected officials accountable for failure. If we do not hold our elected officials accountable, there is barely any use living in a democracy.

If you live in a democracy, anywhere, you may be wondering whether it is fair to hold your elected officials responsible for the immense suffering, death, and economic devastation this pandemic has wrought. You may be carefully weighing claims that your elected officials have failed you against claims that they did the best job they could given the information they had. You may be wondering to what extent any elected official could have predicted such an event.

You may, in particular, be unsure whether China’s behavior (characterized, as Glenn Reynolds correctly has put it, by “dishonesty, incompetence, and thuggery”) absolves our own elected officials of responsibility for this catastrophe. Is it true that China was so dishonest, so incompetent, and so thuggish that our elected officials were unable to limit the damage?

No. This is nonsense.

Here are the documents and dates that demonstrate this.

The Pandemic Checklist

This is the WHO’s influenza pandemic preparedness checklist, published in 2005. “Are you prepared,” it asks officials, “to prevent or minimize the human morbidity and mortality, the social disruption and the economic consequences caused by an influenza pandemic?” The document makes a compelling case that you should be. It explains how to prepare, and why.

The objective of pandemic planning is to enable countries to be prepared to recognize and manage an influenza pandemic. Planning may help to reduce transmission of the pandemic virus strain, to decrease cases, hospitalizations and deaths, to maintain essential services and to reduce the economic and social impact of a pandemic.

In addition, blueprints for an influenza pandemic preparedness plan can easily be used for broader contingency plans encompassing other disasters caused by the emergence of new, highly transmissible and/or severe communicable diseases.

It’s by no means the only such document, but it was enough.

Read it carefully, then ask yourself whether your officials followed these guidelines, before and during this pandemic. It is not reasonable to hold currently-elected officials responsible for the failures of their predecessors. It is reasonable to ask whether they recognized these failures, early in their tenure in office, and worked as assiduously as they should have to rectify them.

A “reasonable government” would have prepared for pandemics in accordance with this model, and it would have executed the plan in a timely fashion.

Governments that failed this test shouldn’t be governing you anymore.

DEFCON-3

A key date. “Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China,” was published in The Lancet on January 24:

We report here a cohort of 41 patients with laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infection. Patients had serious, sometimes fatal, pneumonia and were admitted to the designated hospital in Wuhan, China, by Jan 2, 2020. Clinical presentations greatly resemble SARS-CoV. Patients with severe illness developed ARDS and required ICU admission and oxygen therapy. The time between hospital admission and ARDS was as short as 2 days. At this stage, the mortality rate is high for 2019-nCoV, because six (15%) of 41 patients in this cohort died.

The number of deaths is rising quickly. As of Jan 24, 2020, 835 laboratory-confirmed 2019-nCoV infections were reported in China, with 25 fatal cases. Reports have been released of exported cases in many provinces in China, and in other countries; some health-care workers have also been infected in Wuhan. Taken together, evidence so far indicates human transmission for 2019-nCoV. We are concerned that 2019-nCoV could have acquired the ability for efficient human transmission. Airborne precautions, such as a fit-tested N95 respirator, and other personal protective equipment are strongly recommended. To prevent further spread of the disease in health-care settings that are caring for patients infected with 2019-nCoV, onset of fever and respiratory symptoms should be closely monitored among health-care workers. Testing of respiratory specimens should be done immediately once a diagnosis is suspected. Serum antibodies should be tested among health-care workers before and after their exposure to 2019-nCoV for identification of asymptomatic infections.

January 24 is the very last date on which any any elected official can reasonably claim to have had no idea what we were up against.

On January 24, 2020, I didn’t know enough, personally, to grasp what that article meant. A government that had followed the 2005 WHO guidelines to any reasonable degree, however, would have had in its employ an advisor whose job was to read articles like that one and understand what they meant. In the case of the United States government, we have had, for years, massive federal agencies staffed by people whose entire job is to do that and do it competently.

As a result of the collective crash course we’ve all taken in epidemiology, pandemics, virology, zoonotic disease, and SARS, I’m sure you now understand that article perfectly. You know exactly what those words meant. Many of you, like me, have learned this in the past month. So you also know how little expertise was truly needed, on January 24, 2020, to appreciate that this article could just as well have been titled, “DEFCON-3.”

DEFCON-4

On January 20, the WHO released “Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) SITUATION REPORT.” This, like the report in The Lancet, was in the public domain. We did not need the technologically advanced services of the NSA to obtain this information, nor did anyone need a security clearance to read it.

The Washington Post has reported breathlessly that our intelligence agencies were “blinking red.”

U.S. intelligence agencies were issuing ominous, classified warnings in January and February about the global danger posed by the coronavirus while President Trump and lawmakers played down the threat and failed to take action that might have slowed the spread of the pathogen, according to U.S. officials familiar with spy agency reporting.

But no one needed these intelligence agencies—or a classified report—to understand the situation then. Nor do we need Deep Throat and The Washington Post to grasp it now. To the contrary, the information was in the public domain.

Read the whole report. Note especially that on January 20, the WHO reported the following:

On January 3, South Korean health authorities began strengthening surveillance for pneumonia cases in health facilities nationwide. They also began heightened screening for travelers from Wuhan at all points of entry and implemented quarantine measures for anyone who met the criteria for suspicion. (The report is imprecise about what these measures were.)

Also on January 3, Thailand began screening all passengers arriving by air from Wuhan for respiratory symptoms and febrile illness.

On January 6, Japan’s health ministry informed local health administrators of a respiratory illnesses in Wuhan. They had been made aware of it via “the existing surveillance system for serious infectious illness with unknown etiology.”

On January 7, Chinese authorities identified the pathogen: a novel coronavirus.

Also on January 7, Japan stepped up screening measures for travelers from Wuhan city every point of entry. Quarantines were also “enhanced,” which I presume mean they had already gone into effect.

On January 12, China shared the genetic sequence of the virus.

On January 13, , Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health reported a lab-confirmed case of 2019-nCoV.

On January 15, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare reported the same thing.

On January 16, the Japanese Government scaled up a “whole-of-government coordination mechanism.” They had already developed a test for the virus, which they debuted this day. “Public risk communication” was enhanced. A dedicated hotline was established among relevant government ministers.

On January 20, South Korea reported its first lab-confirmed case of 2019-nCoV. It began “enhancing public risk communication,” although the report is unclear when this began, precisely. Presumably it was between January 3 and this date.

By January 20, Japan had reported tracing and following 41 contacts of the infected person discovered on January 15. Of these, 37 had shown any symptoms. Three had left the country. Japan made efforts to reach one of them; presumably the other two could not be traced.

On January 20, Thailand’s Department of Disease Control scaled up its Emergency Operations Center to “Level 2.” On the same day, or perhaps shortly before, Thailand shared “risk communication guidance” with the public and established a hotline for people returning from Wuhan with relevant symptoms.

On January 20, China reported 278 confirmed cases. Of these, 258 cases were in Hubei Province. Another 14 were in Guangdong; of these, 12 had recently traveled to Wuhan. The other two had not, but they had been in contact with one of these 12 people. Five cases were reported in Beijing. All had recently traveled to Wuhan. One was from Shanghai; she had recently traveled to Wuhan. Of the 258 cases, 51 were severely ill. Twelve were in critical condition, and six were dead.

WHO claims to have been “informing” other countries of these facts, although it is unclear when it did. Certainly, though, every country in the world was informed of all of the above on January 21.

In the same report, WHO asserts that it had activated the “incident management system” in its country, regional, and headquarters offices on January 2. The report is unclear about the dates of the following events, but certainly, well before January 20, it had done the following:

Developed surveillance case definitions for human infection with 2019-nCoV;

Developed “interim guidance for laboratory diagnosis, clinical management, infection prevention and control in health care settings, home care for mild patients, risk communication and community engagement;”

Prepared “disease commodity package for supplies necessary in identification and management of confirmed patients.” (It is unclear what this means, but I assume this included supplies such as swabs and reagents);

Updated its advice for “international travel in health in relation to the outbreak of pneumonia caused by a new coronavirus in China;”

Called upon “global expert networks and partnerships” for laboratory work, infection prevention and control, clinical management and mathematical modelling;

Activated “R&D blueprint to accelerate diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics;”

Worked with “networks of researchers and other experts to coordinate global work on surveillance, epidemiology, modelling, diagnostics, clinical care and treatment, and other ways to identify, manage the disease and limit onward transmission.”

On January 20, all of this information was in the public domain.

Mardi Gras culminated on February 25

Mayor LaToya Cantrell has said she failed to cancel Mardi Gras because the federal government failed to provide her with a “red flag.”

This does not pass the “reasonable official” test.

We may reasonably ask our elected officials to read a newspaper every day. It is unreasonable, if you are an elected official, to refuse to read a newspaper. This story was on page A1 of the New York Times on February 2.

A reasonable elected official would know enough about infectious disease, in the year 2020, to understand that Mardi Gras is, inherently, “an epidemiologist’s nightmare.”

A reasonable official, knowing that Donald Trump is the head of our federal bureaucracy, would have thought, “Our federal bureaucracies are in disarray. I must make this decision myself. The buck stops with me.”

A reasonable elected official would have consulted the website of the WHO, seen that report, and read it for herself.

A reasonable elected official would have cancelled Mardi Gras.

A reasonable elected official would take responsibility for this failure by resigning.

A reasonable public would not re-elect this official.

No matter what your elected officials say, the WHO report on January 20 was dispositive. Any responsible public official could have—and should have—known, by that day, that a new, lethal, unusually contagious respiratory virus had been unleashed upon the world and was transmissible from human to human.

January 20 is the key day. Any politician who failed to take this as an emergency, on that day, and to behave as if he or she took it as an emergency, should resign.

(March 13: “I don’t take responsibility at all.”)

Crystal Clear

On January 21, the WHO issued another report titled Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) SITUATION REPORT It reiterates the information above, but adds critical details. Among them:

Another 32 cases—an 11 percent increase—had been reported since the report published only one day before. These were reported in seven new provinces and two new municipalities.

One case was reported in Taiwan. This patient had never visited traditional markets or hospitals in Wuhan. He’d had no contact with any known, confirmed cases, nor contact with live animals. The date of the onset of his symptoms was January 11.

This report indicated what we all now know: R-naught? Terrifyingly high. Spread of the disease? Already over a huge geographic area. Human-to-human transmission? You bet. Asymptomatic transmission? Sure sounds like it. Long incubation period? Yep.

None of this was cause for panic—there wasn’t enough data for that yet. But it was cause for every government on this planet to ensure all the elements of the pandemic plan were ready to be deployed at a moment’s notice—including communicating the risk to citizens.

Return to the WHO’s 2005 Pandemic checklist. Note the stress it places on “communication strategy.”

On January 3, South Korea launched their plan.

Any government that had not launched its pandemic plan by January 24, at the latest, was dangerously incompetent and should be held accountable for per capita death and damage to its citizens in excess of that suffered by South Korea.

China’s failure to cope with the pandemic competently or honestly did not prevent South Korea from launching its plan on January 3. If your elected officials tell you that China’s dishonesty prevented them from launching their plan on January 3, you should ask, “Why?”

It is not true that “no member of the political establishment” sounded the warning any earlier.

January 29: Joe Biden wrote of his alarm, prominently, in USA Today:

January 29: Peter Navarro sends his memo to the National Security Council.

January 22. “We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”

February 2. “We pretty much shut it down coming in from China.”

February 22. “The Coronavirus is very much under control in the USA. We are in contact with everyone and all relevant countries. CDC & World Health have been working hard and very smart. Stock Market starting to look very good to me!”

February 26. “We’re going very substantially down, not up. ... We have it so well under control. I mean, we really have done a very good job.”

February 26. “This is a flu. This is like a flu. ... It's a little like the regular flu that we have flu shots for. And we’ll essentially have a flu shot for this in a fairly quick manner.”

February 27. “It’s going to disappear. One day—it’s like a miracle—it will disappear.”

March 8. “No, I’m not concerned at all. No, I’m not. No, we've done a great job.”

March 27. “I don't believe you need 40,000 or 30,000 ventilators. You know, you’re going to major hospitals sometimes, they’ll have two ventilators. And now, all of a sudden, they’re saying, can we order 30,000 ventilators?”

March 27. “You call it germ, you can call it a flu. You can call it a virus. You can call it many different names. I'm not sure anybody knows what it is.”

If your elected officials insist that this pandemic “came out of nowhere (March 6, Trump),” or that “Nobody had ever seen anything like this before,” (March 19, Trump) or that “Nobody would have ever thought a thing like this could have happened,” (March 26, Trump), then either they (a) are lying; (b) cannot read; (c) won’t read; (d) don’t understand what they read; (e) do not care what they read; or all of the above.

They cannot pass the “reasonable official” test.

April 12. US Death toll: 22,960. Confirmed cases: 574,138.

Project PREDICT

Two months before the novel coronavirus is thought to have begun its deadly advance in Wuhan, China, the Trump administration ended a $200-million pandemic early-warning program aimed at training scientists in China and other countries to detect and respond to such a threat.

The PREDICT project, launched in response to the 2005 H5N1 “bird flu” scare, gathered specimens from more than 10,000 bats and 2,000 other mammals in search of dangerous viruses. …

Meanwhile, in Rwanda, scientists who had been trained in the PREDICT program triggered early social distancing measures, Mazet said. “I do think that what we were doing has changed the outcomes for a lot of countries,” she said.

“But unfortunately, not our own,” she added.

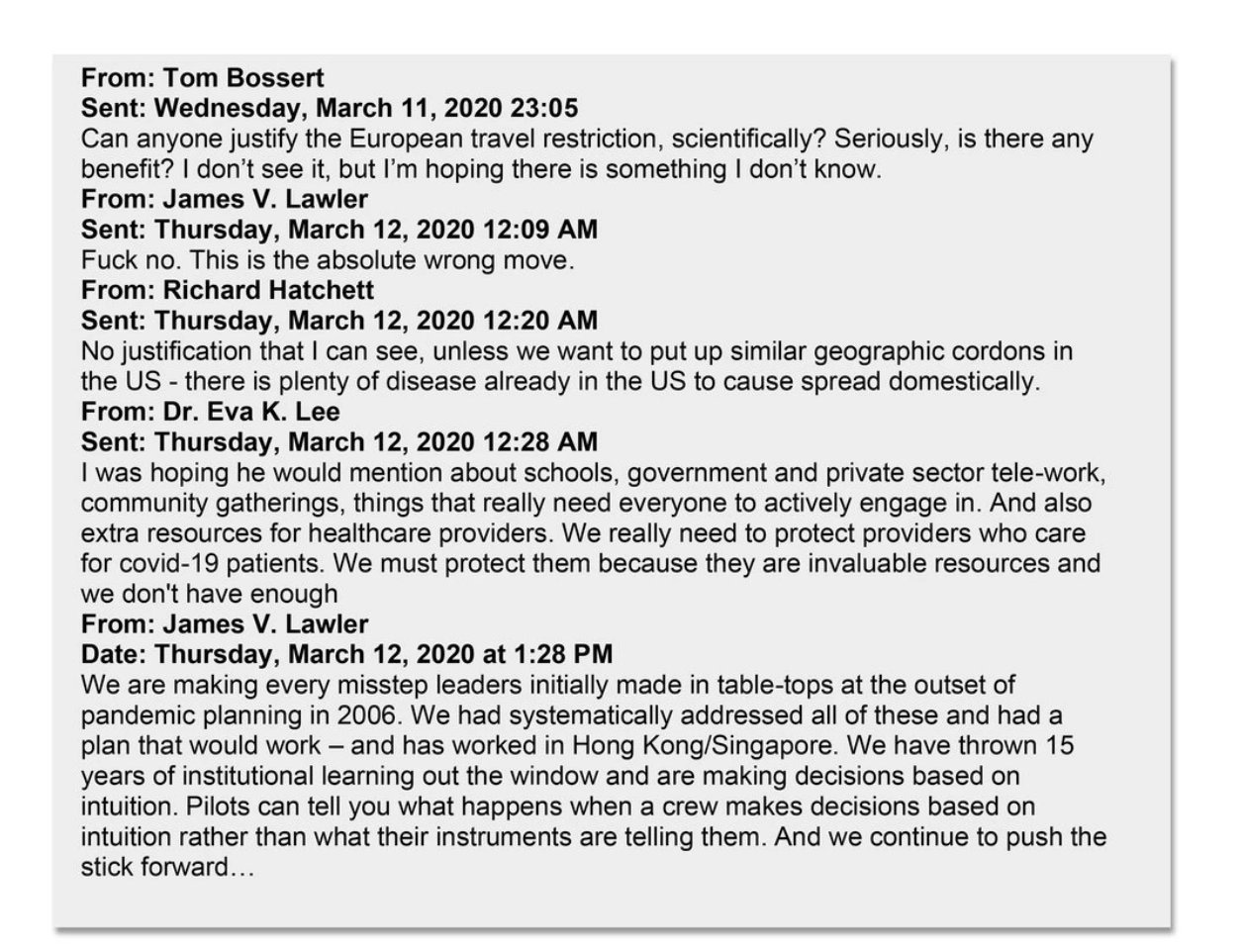

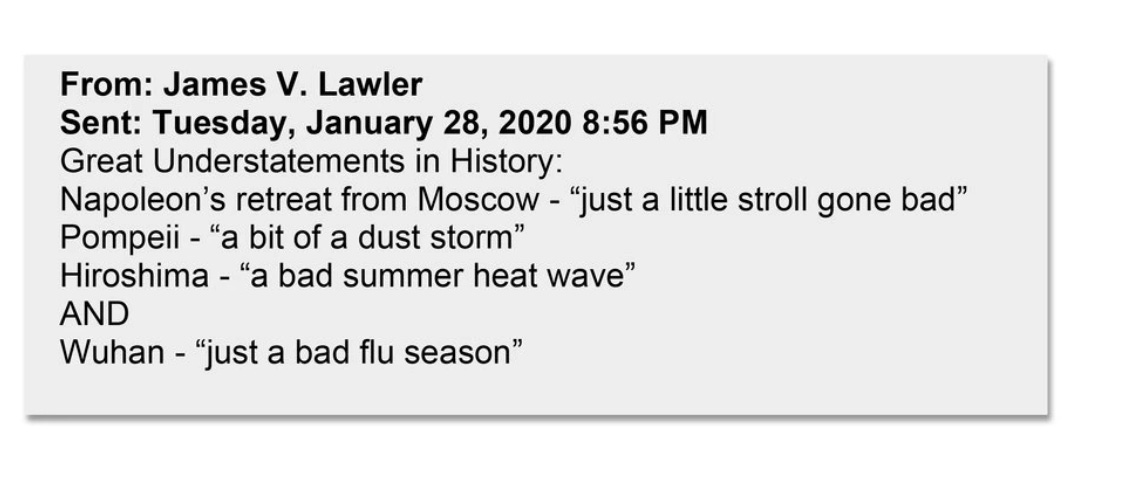

The RED DAWN e-mails

Read all 80 pages of the e-mails. Really, read them, if you’re in any doubt at all about whether we could have known.

January 28: Carter Mecher, who wrote the CDC’s 2007 Pandemic plan:

January 28: James Lawler, director of clinical and biodefense research at the National Strategic Research Institute:

February 9.

February 18.

A debate

So, I am very curious to know what Lieutenant Colonel Thorp’s response could possibly be—and I’m sure you are, too.

Stay tuned to learn.

Then we can put it to a vote.

This is a great example of hindsight bias. As an accessible example, it is easy to find folks who will tell me I was an idiot for picking the Pats to win the Super Bowl when a blind man could see the KC Chiefs were the best team. Backing Brady and Belichick was a lot easier to explain in December, before they lost.

Or forget sports - the investing community sees hindsight bias all the time. There is always a genius who said to buy [insert Hot Stock here] a year ago. Or go back to 2008 - there had been widespread talk for years about regional housing bubbles. Almost no one predicted it would end with the near-death experience for the global banking system.

I'd be more impressed with this presentation of it was contrasted with the alarms and response to the 2009 swine flu and the 2003 SARS outbreak, which are comparable bugs. Also comparable in terms of public concern might be the 2015 Zika scare and the 2014 Ebola scare.

To pick one specific point, with hindsight its obvious that cancelling Mardi Gras (a 40 day event?) would have been a great move. As a matter of political (ie, human) reality, it might be easier for a mayor to cancel the Super Bowl. The cultural significance of Mardi Gras to New Orleans and the public weight behind having it go forward would have made it impossible for a mayor, acting alone, to cancel it. Cover from the governor and the President might have been enough. (Do let me add, major cities cancelled St. Patrick's Day parades, but that was March 17.)

If the conclusion is that nearly every public official in the West was unreasonable and incompetent, I'd re-examine the argument that led me to that. These are democracies - the people of New Orleans elected a mayor, not a nanny. Absent public support in the moment, bold but unpopular measures are going to be rare.

I'm stuck for examples. The mayor of San Francisco basically kicked crowds out of the Warrior home games on Mar 11. They were set to play in an empty arena but the NBA suspended their season the next day after a player tested positive. NCAA took that excuse to cancel their tournament.

Oh, a bonus quarrel: Joe Biden's "leadership" was a partisan point-scoring attack guaranteed to turn off half the country. And talking about all the international good-fellowship he'd have funded years earlier? Come on, man (to quote a future President.) Nothing in his op-ed mentioned specific stuff like tests, PPE and ventilators.

I did like this from his piece, my emphasis:

"To be blunt, I am concerned that the Trump administration’s shortsighted policies have left us unprepared for a dangerous epidemic that will come **sooner or later**."

Sooner or later?!? A clarion call on Jan 29, when every responsible official should have understood that the future is now!

FYI, DEFCON counts down...DEFCON 1 is when the missiles are flying. DEFCON 5 is where we're all safe and secure in our quiet little lives.